Information Philosophy, Part 1

Spring is an interesting time of the year, and it should be celebrated correctly. A deep, heavy, multi-part holivar about the nature of information is, I think, a very good way to celebrate spring on Gikttimes.

I apologize in advance for the fact that there will be a lot of letters. The topic is extremely complex, multidimensional and extremely neglected. I would be glad to put everything in one small article, but then you will inevitably get a hack with gaping logical holes, obstructed questions and chopped off storylines. Therefore, I suggest that the esteemed public have a little patience, get comfortable and enjoy the calm and thoughtful immersion in the questions that were related to “no one knows”.

Content

Introduction

Brief Background

The plot of the first: materialism vs. idealism

The plot of the second: the search for the basis of reliable knowledge

The plot of the third: determinism vs. free will

The plot of the fourth: the Turing machine

Chapter 1. Dualism

Metaphor "book"

Physical reality totality

Information reality totality

Totality inseparability of realities

Reification

Chapter Summary

Continuations:

Chapter 2. The existence of information

Chapter 3. Foundations

Chapter 4. Systems

Chapter 5. Purposeful Actor

Chapter 6. Creatures

Chapter 7. System Formation | Conclusion

Brief Background

The plot of the first: materialism vs. idealism

The plot of the second: the search for the basis of reliable knowledge

The plot of the third: determinism vs. free will

The plot of the fourth: the Turing machine

Chapter 1. Dualism

Metaphor "book"

Physical reality totality

Information reality totality

Totality inseparability of realities

Reification

Chapter Summary

Continuations:

Chapter 2. The existence of information

Chapter 3. Foundations

Chapter 4. Systems

Chapter 5. Purposeful Actor

Chapter 6. Creatures

Chapter 7. System Formation | Conclusion

Introduction

Now, when this text is being written, a very funny situation has developed. Society has rapidly entered the information age, but the ideological basis used to understand what is happening has remained, at best, inherited from the beginning of the industrial era. Now there is no generally accepted way to inscribe the concept of “information” into the picture of the world so that the resulting result does not contradict the phenomena that we obviously and everywhere see.

')

We learned quite well how to obtain information, store it, transmit, process and use it. In fairness it should be noted that we all know perfectly well what information is. But the knowledge is implicit. Implicit knowledge is a matter of course, well understood for domestic consumption, but unsatisfactory for productive collective use.

Tasks of information philosophy:

- Find and eliminate obstacles that prevent the transfer of "information" from implicit knowledge to explicit.

- To form a metaphysical system into which the information processes that have already in fact become part of our everyday life could organically and consistently fit into.

In my further presentation, I will proceed from the fact that philosophy is primarily a tool that forms conceptual devices and the rules for their use. This is a little different from what is usually meant when the word "philosophy" is pronounced. It is believed that philosophy should provide answers to questions about the existence of things and explain some of the most common laws of the world order. But still, somehow, it turns out that, before starting to talk about the world order, it is not superfluous to develop a language suitable for these arguments not to be deliberately meaningless.

It is the task of forming a language, and not the search for Truths, that will form the basis of the method that I will try to adhere to in the further narrative. In order to demonstrate this method convexly, I will give several examples, including those from related areas of philosophizing:

- Does God exist?

The question methodically (according to the applied method basis) is not correct. The correct wording is: How should one reason about God so that reasoning makes sense? - Are there objective laws governing the world?

The correct wording: How should one speak about the existence of the laws of the universe so that this speaking is not a waste of time? - What comes first - matter or consciousness?

The correct wording: How should one speak about primacy, about matter and about consciousness, so that what was said was not a meaningless pastime? - What is information?

The correct wording is: How should one reason about information so that these reasonings make sense?

Let us proceed from the fact that the philosophy of information should become the very linguistic tool adequate to our needs, which will allow us not to go into a logical impasse every time when it comes to the nature of information, consciousness, management, system formation, complexity and other now pretty overgrown with myths things.

In order to demonstrate the power of the instrumental approach, it is appropriate to carry out the following historical illustration. Once upon a time, the question of what is moving around, the Earth around the Sun or the Sun around the Earth, was a very burning dilemma. It even got to the point that physical massacres of ideological opponents were common practice. Now, having learned to talk about movement and having figured out that the key point of this reasoning is the choice of the observer position, we have the opportunity to use the heliocentric system to our convenience, and geocentric in our everyday affairs. When we say that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, we implicitly mean that the sun goes, although from the point of view of the heliocentric system it is a lie. The difference between what was and what has become is only in the fact that we have acquired a conceptual apparatus that allows us to more adequately talk about movement. The ability to translate reasoning in a constructive way, and thus reconcile opposing positions is not the only useful function of the instrumental approach. A no less useful function is the forced closure of those problems for which it is found that for them there are no ways of reasonably reasoning.

The instrumental approach to philosophizing, of course, has its limitations. In particular, the question of how to distinguish productive from counterproductive reasoning should remain constantly open and debatable. You can, of course, focus on logical consistency or practical utility. But this and the other are very vague criteria. It seems to me that one can only hope that the discussion about the usefulness of things is usually much simpler and more productive than the discussion about the existence of something that no one can either confirm or deny. In the end, the utility - this is the very thing by which it is best to organize a vote with their feet.

I do not want to say in any way that the instrumental approach is my invention. It is described in a huge number of philosophical texts, and even more productively used. This, in general, the obvious thing had to be put into the introduction only because if it was not focused on her in advance, too much of what would be presented further would seem wild and sometimes self-contradictory. The specificity of the problem is such that for its solution it will not be possible to keep within the framework of simple truths and habitual logical constructions. I repeat once again: we will not look for the eternal and immutable for ever and ever Truths with a capital letter, but just try to find such a language, the reasoning on which about information, systems and management will not lead us every second to a logical impasse.

Brief Background

This section is not intended to systematically present the history of the development of world philosophical thought. The task is only to inscribe further reasoning in the existing context, without reference to which they cannot be understood and accepted.

The plot of the first: materialism vs. idealism

The materialists believed and believe that "for real" there is only physical reality (in the words of Democritus, "atoms and emptiness"). Accordingly, the fact that we have the opportunity to observe how ideas are only in some mysterious “special way” the movement that takes place, conditionally speaking, of atoms in emptiness. What this special feature of a “special image” may consist of is usually not clarified, and if you try to clarify this question, the school textbook of physics is clumsily cited at best.

Idealists believed and believe that "truly" there are only ideas, and what we perceive as the surrounding gross physical reality is either an illusion or the result of witchcraft.

The arguments in favor and in the refutation of these points of view are numerous, varied and all are extremely weak, even though in the 20th century materialists millions of times experimentally confirmed that if a person is kept locked up and not fed, then he stops thinking about ideas and starts thinking about food.

There is an opinion (in particular, expressed by Merab Mamardashvili in “Introduction to Philosophy”) that real philosophers never seriously considered the question of what is primary, consciousness or matter. If we approach this so-called “main question of philosophy” from the position described by me in the introduction of the instrumental approach to philosophizing, then an interesting thing comes to light immediately. In order to either discuss the existence of matter without implying the presence of consciousness at least in the form of an implicit observer, or reasoning about the functioning of consciousness without material realization had at least some meaning, we should be able to get into either a situation correspondingly without consciousness or a situation without matter . And the one and the other is impossible, and therefore no argument about primitiveness can make sense. Thus, the question “How should one talk about ...?” Applied to the root cause gets the answer “None” .

For our purposes, probably the most valuable and useful result of the discussion between materialists and idealists is the very question of the existence of material and non-material entities. In particular, the division of the world into extended (res extensa) and imaginable things (res cogitans), introduced by René Descartes, turned out to be very useful and productive. While humanity in its practical activity was concentrated on the study and creation of extensive things separately, and on operating with things imaginable separately, the separation of the world did not cause any particular inconvenience and was only a theoretical incident, which then somehow had to be remembered to be allowed. With the advent of the information technology era, we have learned to create material (res extensa) things entirely intended for manipulating intangible (res cogitans) entities, and therefore, the qualitative gluing of separated worlds has become a task that cannot be solved by the philosophy of information.

The plot of the second: the search for the basis of reliable knowledge

The search for bases for reliable knowledge runs like a red thread through the whole of European philosophy. From the point of view of practical benefits, this topic turned out to be the most effective, providing the basis of the natural science method and, as a result, giving rise to all that technological splendor, the fruits of which we have the opportunity to enjoy.

The central idea underlying the rationale is the idea of objective reality perceived by the perceiving subject. Moreover, each time when it is said about the existence of something in objective reality, it is necessary to determine the subject who perceives this reality in order to comply with the methodological correctness.

The subject of the “perceiving subject” was comprehensively explored by the existing philosophical tradition, and could serve as a good starting point for the philosophy of information, if it were not for two important points:

- The perceiving subject is a passive being. He perceives objective reality, receives reliable knowledge ( information ) about it, but in the discourse about what information is, the concept of the perceiving subject cannot be the starting point, because it already includes the concept of information. In essence, “information” turns out to be a concept, through which it jumped in order to run further. Therefore, we will have to dig a little deeper, and subjectology to build not from the perceiving subject, but from something else. In particular, further we will have a purposefully acting subject who not only “reflects” objective reality, but lives inside it, and he needs information not just like that (to “reflect”), but for some purpose . Having outdated the topic of “the goal of the subject” and considering the existence of goals as something taken for granted and not discussed, it is impossible to speak about the meaning of information. And meaningless information is no information at all.

- The perceiving subject is an infinitely lonely being. The whole world surrounding the perceiving subject is for him an objective reality. Even those objects with which the perceiving subject guesses its essential affinity are for him not subjects, but objects, reliable knowledge about which he seeks to obtain. From the point of view of information philosophy, such a harmonious, but sad picture of the world turns out to be completely unacceptable, since it does not involve communication of subjects. Communication requires at least two subjects, and in the picture of the world divided into two parts - the perceiving subject and the reality perceived by it, the subject is by definition one. We will simply have to leave the good old cozy concept of the thinking (and therefore existing) perceiving subject. We will try not to get lost.

Having lost the usual way of deriving the foundations of reliable knowledge from the concept of “perceiving subject”, we will be forced to find an adequate substitute. Otherwise, the resulting metaphysical system will be deprived of justification, and therefore will not be suitable for use.

The plot of the third: determinism vs. free will

It so happened that from the point of view of the philosophical basis of scientific knowledge (epistemology), objective reality is arranged in such a way that there is no place for free will in it. The maximum that is is an accident (in particular, quantum uncertainty), from which free will cannot be derived anyway. But, on the other hand, for the philosophy of morality (axiology), the fact of the existence of free will is a necessary condition. Among other things, the existence of free will is rather easily inferred directly from “I think, I exist,” which pretty adds spice, since the basis of natural science knowledge is also derived not from somewhere, but from the same primary fact, from “I think, I I exist. "

In short, from the true antinomy that has arisen we will try to extricate ourselves by getting rid of the passivity of the perceiving subject. Acting in the world, the subject will inevitably become ours, the world, part of it, and this will allow us in those aspects that the subject does not influence, to have determinism, and in the nature and results of its activities - free will.

The problem of "determinism vs. free will ”is a good reason to talk about the nature of causality, because determinism is predestination, given the rigidity of causation.

Arguing about a purposefully acting subject, it is impossible (and not necessary) to ignore the conversation about how it can happen in general that cause-and-effect relationships take place in our world.

The plot of the fourth: the Turing machine

In the second half of the 20th century, philosophers had at their disposal a curious toy - a Turing machine that can perform any feasible computation. Since brain activity is considered as information processing, that is, calculation, it turned out that either Turing-complete calculator can be taught to think completely human, or to assume that there is some unknown secret component in thinking, and then ... further reasoning inevitably leads to mysticism Or to traditional mystic (God), or unconventional (information fields), or pseudoscientific (an attempt to cling to quantum uncertainty).

Mysticism is an attempt to explain the incomprehensible through the obviously unknowable. Pure scam. We will not do that. But the non-realizability of human thinking with the Turing complete calculator will also be proved. To do this, we just need to learn a little more adequately talk about information, as well as its processing.

Chapter 1. Dualism

Metaphor "book"

Consideration of a book, an ordinary paper book, this subject, which is very widespread in our everyday life, will help us to feel how the material and the ideal are intertwined into a single whole.

From one point of view, a book is a material object. It has a mass, volume, takes some space in space (for example, on a shelf). It has chemical properties. In particular, it burns quite well.

From another point of view, a book is an intangible object. Information. Speaking about the book, you can talk about the plot and the relationship of the characters (if it is fiction), the truth of the stated facts (if it tells about real events), the completeness of the disclosure of the topic and other things, certainly not having neither mass nor chemical properties.

Take for example the tragedy of William Shakespeare's "Hamlet." Imagine that you have this book in your hand. Naturally, you took a material object in your hand. The plot of "Hamlet" in the hand can not be taken. The book is not very thick, the mass is not very big. Pages smell good. You can conduct a chemical analysis and find out that this item consists mainly of cellulose with admixtures of paint, glue and other substances. In solid state of aggregation. In material terms, not much different from the boulevard novel standing next to the shelf. But it is clear that there is something besides atoms in this subject. Try to find. Take a microscope and see. We will see the interlacing of stuck together wood fibers and their adhesion to pieces of paint. Take a microscope stronger, and see a lot of interesting things. But all this interesting will have nothing to do with “to be or not to be”, nor to the idea of revenge for treason and murder. No matter how we investigate the material component of the book, we will not find the information component. Only atoms and emptiness. But, nevertheless, it is absolutely possible to say that in “Hamlet” there is a plot, and characters, and the famous “to be or not to be”. And for the detection of this does not need to take a microscope. You just need to open the book and start reading. What is interesting, from the informational point of view, the material layer goes into the background so far that it turns out to be all the same to us, a book is made of paper or, say, of parchment. In the end, Hamlet can also be read from the screen of the book reader, and there are absolutely no wood fibers with pieces of paint stuck to them.

So, we have two ways of looking at the “Hamlet” book: materialistic, in which you can see anything other than the idea, and idealistic, in which the interlacing of fibers is completely unimportant, but the interweaving of the plot is important. And, nevertheless, the subject we have is the same. The only difference is in our own approach to it. That is, in what we are going to do with it - to weigh or read. If we are going to weigh, then we are completely 100% tangible, and if we read, then we are 100% intangible.

A reasonable question arises: is it possible to somehow contrive and take a look at this subject so as to simultaneously see two of its incarnations? It is possible and necessary, but I cannot say that it is easy to do. It is very difficult. This requires considerable effort and the use of a whole arsenal of tools and techniques, which I will try to talk about later. This is necessary, if only because the methods of bringing together the objective and the subjective into a single whole are the metaphysical basis of the philosophy of information. But before engaging in the gluing of the hypostases of reality, it will be useful to realize the depth of the problem.

Physical reality totality

The concept of "material" can be defined in different ways. For example:

- Everything objectively existing. This interpretation is directly or indirectly used by the classics of materialism. For example, Lenin wrote that objective existence is a function of matter. For an information philosophy, such an approach is not suitable in the first place because either it immediately materializes informational entities or deprives them of their right to objective existence. In the first case, we fall into the trap of reification (let's talk about its inadmissibility below), and in the second case, we are at a standstill in front of the simplest easily observed phenomena. For example, try to draw a happy ending to “Hamlet” so that it does not cease to be “Hamlet”. Or, alternatively, change the thousandth sign in the number of "pi". Both are ideal entities, but something irresistibly holds them in objective reality.

- Everything that is different from the mental and spiritual. Such a definition is not suitable, since we do not yet know what the mental and spiritual are. That is informational. At this point in the story, we are not yet able to reason about information, and therefore we cannot make decisions about what is an informational entity and what is not.

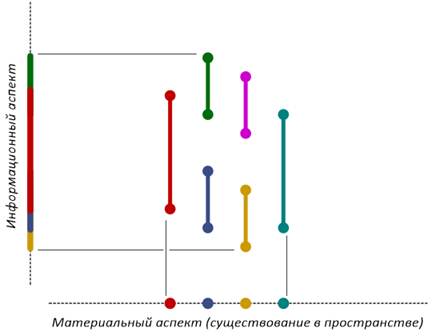

- Everything that exists in physical space. That is what Descartes defined as “res extensa”. Body extended. , , , . , . , . , , – (, ) , . , , , , , «».

, .

– . , , . , . , .

, , – , , . , , , , . , , « », . , , , - , .

, « » , , . «», . , « » , «», .

, , , . , , , , , , . , , , «» – , .

, , - , , , .

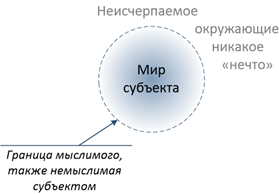

, , . , - . , , . -, . . , , ( ), , . , , ( , , ). , , . . , . «- » , , , , . , , , .

, . . , , . , . . - . , «», , , .

, , :

- . «?», : .

- . , , .

- . , ( – ). - . , , .

. , , , . ( , ), – , , – (, ) .

. . , , , , , , , , , . , .

, , , . , , . , .

, . , . , , , :

- , ( ) .

- , , , , , .

- . , . , , «», «», «», «», «» , , , « » . .

- , . , . . . , .

- , , , . , , . , ( ) . «» – «», , .

- , , . , , , , , . «-» .

, , , . . , - , , , , , . , , , , , , .

, , ( ), . , , , .

, – . , – . . , , . , .

:

, . . , ,– «» . , , , , . ( ), . , – , . . , , , , , , . , , . . - , .

, . , :

)

)

, , , , . , , , . , , . , . . , – , . , , , «» ( ) .

, , , , - ? , - , , . , , - , . . , , .

, , , – . – , . , , «».

– , , , «», , . , , , , . . , , . , , . , , , «» , , «».

– , . , . , « » «». .

, , :

, , . , , .

, , – , . . , , ( ). , «?» , , , .

Let's practice a little bit:

- ? . . – .

- 2? Weird question. , . . , , , - , 2, . , , « » 2 , . «+=4» , , , , « » . , 2 , , . 1 3 . , , , 2 . - 2 (, - « ») , . ( , ?) « ?» 2.

- ? :

- . . , , – , , .

- , . , , . , . , , .

- . . , , – , , .

- ? -, , , . - . «ru.wikipedia.org». , .

- «»? , . , , . . , - «» ( ), «» , . « » – .

- . OK. ? . , ? , , « ?». – . , , . , , , .

- ? , ? . . . , , . , , .

- Does God exist? And if so, where? The naive childish answer "on a cloud" is obviously false, and almost any believer will confirm this. Somehow, it turns out that any more or less adequate answer to this question (“in the souls of believers,” “everywhere where good is done,” etc.) is very little similar to spatial localization. Apparently, the mystics of antiquity understood that the desire to reify God would be extremely great, and therefore the religions they created were explicitly banned from any attempt to depict God in bodily form. Judaism and Islam managed to keep this ban, but Christianity, due to some of its inherent characteristics, could not avoid slipping into the unbridled reification of God. However, both Judaism and Islam did not manage to completely avoid the reification of God. In both of these religions, God is hidden in the texts of their scriptures. Among the Jews, this is most clearly expressed in their ridiculous “Gd”, and among Muslims, towards an incredibly reverent attitude towards copies of the Quran and the direction towards Mecca.

I had to dwell on the topic of “reification” in such detail because the topic “information” is one of those topics that is most strongly elicited by reification. We are so accustomed to “transmit” information by word of mouth, “pouring” it onto a disk, “storing” it in our heads, “processing” it in a computer, that it seems to us as some kind of “subtle substance” that somewhere thickens, somewhere saved, somewhere travels from one point of space to another. This is such a strong and obvious metaphor that we even find it hard to imagine how we can do without this coarse reification. Once again, let's return to our book example. If information is some kind of thin substance condensing inside a book, then in the printing press on which it was made there must be some devices pumping this “thin substance” into the product. But we know exactly how books are made. Moreover, we know exactly how the book-making machines are made. The press does not deal with anything except placing the ink molecules on the fibers of the paper. No "thin substance" simply does not exist. If we want to learn how to talk about information in a reasonably useful way, then we simply have to learn how to talk about it, without allowing for reification.

Chapter Summary

The first task that the philosophy of information has to solve is the elimination of the most insidious logical traps that prevent starting any productive dialogue about the existence of intangible entities, namely:

- meaningless discourse about the root cause of matter or consciousness;

- the underdetermination of the concept "matter";

- habits of reification, which immediately emasculates any discourse on the intangible.

The “book” model object introduced at the beginning of the chapter not only allows one to play with separate reference to the material and non-material aspects of reality, but also gives some hints as to how these aspects can be combined into a single whole.

Basic concepts and concepts:

- The material world as the world of things that exist in physical space.

- The intangible world as the world of things, the localization of which in the physical space is a logical error.

- Reification as a logical fallacy in attributing material existence to intangible things.

- The technique “where does it exist?” Allows you to quickly figure out which of the facets of reality is the subject of discussion. If the conversation is about a thing that takes place in physical space, then this thing is material. If the thing has no place in space, then it is non-material. In particular, the information spacesuit mentioned in this chapter is a mental construct, and therefore an attempt to draw the line between the imaginable and the unthinkable somewhere in space is already a logical error in itself.

- Information suit of the subject - the totality of everything imaginable by the subject.

Continued: Chapter 2. The existence of information

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/403225/

All Articles