Quantum entanglement without confusion - what is it

Introduction

There are a lot of popular articles about quantum entanglement. Experiments with quantum entanglement are quite spectacular, but no prizes have been awarded. Why are such experiments so interesting for the average man not of interest to scientists? Popular articles talk about the amazing properties of pairs of entangled particles - the impact on one leads to an instantaneous change in the state of the second. And what is the meaning behind the term "quantum teleportation", about which we have already begun to say that it is occurring with superlight speed. Let's look at all this from the point of view of normal quantum mechanics.

What is obtained from quantum mechanics

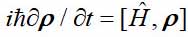

Quantum particles can be in two types of states, according to the classic textbook of Landau and Lifshits - pure and mixed. If a particle does not interact with other quantum particles, it is described by a wave function that depends only on its coordinates or momenta — such a state is called pure. In this case, the wave function obeys the Schrödinger equation. Another option is possible - the particle interacts with other quantum particles. In this case, the wave function relates already to the entire system of interacting particles and depends on all their dynamic variables. If we are interested only in one particle, then its state, as Landau showed even 90 years ago, can be described by a matrix or a density operator. The density matrix obeys an equation similar to the Schrödinger equation

')

Where

Is the density matrix, H is the Hamilton operator, and parentheses denote the commutator.

Is the density matrix, H is the Hamilton operator, and parentheses denote the commutator.Landau brought him out. Any physical quantities related to a given particle can be expressed in terms of the density matrix. This condition is called mixed. If we have a system of interacting particles, then each of the particles is in a mixed state. If the particles are scattered over long distances, and the interaction disappears, their state will still remain mixed. If each of several particles is in a pure state, then the wave function of such a system is the product of the wave functions of each of the particles (if the particles are different. For identical particles, bosons or fermions, you need to make a symmetric or antisymmetric combination, see [1], but this later. Particle identity, fermions and bosons - this is already relativistic quantum theory.

The entangled state of a pair of particles is a state in which there is a constant correlation between physical quantities related to different particles. A simple and most common example is that a certain total physical quantity is preserved, for example, the total spin or the angular momentum of a pair. A pair of particles is in a pure state, but each of the particles is in a mixed state. It may seem that a change in the state of one particle will immediately affect the state of another particle. Even if they are scattered far away and do not interact, this is what is expressed in popular articles. This phenomenon has already been dubbed by quantum teleportation. Some of the illiterate journalists even claim that the change happens instantly, that is, it spreads faster than the speed of light.

Consider this from the point of view of quantum mechanics. First, any effect or measurement that changes the spin or angular momentum of only one particle immediately violates the law of conservation of the total characteristic. The corresponding operator cannot commute with full spin or full angular momentum. Thus, the initial entanglement of the state of a pair of particles is disturbed. The spin or moment of the second particle can no longer be unambiguously associated with that of the first. You can look at this problem from the other side. After the interaction between the particles has disappeared, the evolution of the density matrix, each of the particles is described by its equation, in which the dynamic variables of the other particles are not included. Therefore, the impact on one particle will not change the density matrix of another.

There is even the Eberhard theorem [2], which states that the mutual influence of two particles cannot be detected by measurements. Suppose there is a quantum system, which is described by a density matrix. And let this system consist of two subsystems A and B. Eberhard's theorem says that no measurement of observables associated only with subsystem A affects the measurement result of any observables that are associated only with subsystem B. However, the proof of the theorem uses the wave reduction hypothesis a function that has not been proven either theoretically or experimentally. But all these arguments are made in the framework of non-relativistic quantum mechanics and relate to different, not identical particles.

These arguments do not work in a relativistic theory in the case of a pair of identical particles. Let me remind you once again that the identity or indistinguishability of particles is from relativistic quantum mechanics, where the number of particles is not preserved. However, for slow particles, we can use a simpler apparatus of nonrelativistic quantum mechanics, simply by taking into account the indistinguishability of particles. Then the wave function of the pair must be symmetric (for bosons) or antisymmetric (for fermions) with respect to the permutation of particles. Such a requirement arises in the relativistic theory, regardless of the particle velocity. This requirement leads to long-range correlations of a pair of identical particles. In principle, a proton with an electron can also be in an entangled state. However, if they disperse by several tens of angstroms, then interaction with electromagnetic fields and other particles will destroy this state. Exchange interaction (this phenomenon is called so) acts on macroscopic distances, as experiments show. A couple of particles, even if they are divided into meters, remain indistinguishable. If you take a measurement, then you do not know exactly which particle the measurement quantity belongs to. You measure with a pair of particles at the same time. Therefore, all spectacular experiments were carried out with exactly the same particles - electrons and photons. Strictly speaking, this is not exactly the entangled state that is considered in the framework of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, but something similar.

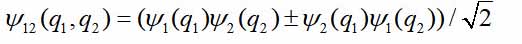

Consider the simplest case - a pair of identical noninteracting particles. If the velocities are small, we can use nonrelativistic quantum mechanics taking into account the symmetry of the wave function with respect to the permutation of particles. Let the wave function of the first particle

, the second particle -

, the second particle -  where

where  and

and  - dynamic variables of the first and second particles, in the simplest case - just coordinates. Then the wave function of the pair

- dynamic variables of the first and second particles, in the simplest case - just coordinates. Then the wave function of the pair

The + and - signs refer to bosons and fermions. Suppose that the particles are far from each other. Then

localized in remote areas 1 and 2, respectively, that is, outside these areas they are small. Let's try to calculate the average value of some variable of the first particle, for example, coordinates. For simplicity, one can imagine that only coordinates are included in the wave functions. It turns out that the average value of the coordinates of particle 1 lies BETWEEN regions 1 and 2, and it coincides with the average value for particle 2. It is in fact natural - the particles are indistinguishable, we cannot know which of the particles has coordinates. In general, all the average values of particles 1 and 2 will be the same. This means that by moving the localization region of particle 1 (for example, a particle is localized inside a crystal lattice defect, and we move the entire crystal), we act on particle 2, although the particles do not interact in the usual sense — through an electromagnetic field, for example. This is a simple example of relativistic entanglement.

localized in remote areas 1 and 2, respectively, that is, outside these areas they are small. Let's try to calculate the average value of some variable of the first particle, for example, coordinates. For simplicity, one can imagine that only coordinates are included in the wave functions. It turns out that the average value of the coordinates of particle 1 lies BETWEEN regions 1 and 2, and it coincides with the average value for particle 2. It is in fact natural - the particles are indistinguishable, we cannot know which of the particles has coordinates. In general, all the average values of particles 1 and 2 will be the same. This means that by moving the localization region of particle 1 (for example, a particle is localized inside a crystal lattice defect, and we move the entire crystal), we act on particle 2, although the particles do not interact in the usual sense — through an electromagnetic field, for example. This is a simple example of relativistic entanglement.No instantaneous information transfer due to these correlations between the two particles occurs. The apparatus of relativistic quantum theory was originally designed so that events that are in space-time on opposite sides of the light cone cannot influence each other. Simply put, no signal, no impact or disturbance can travel faster than light. Both particles are in fact the state of one field, for example, an electron-positron one. By acting on the field at one point (on particle 1), we create a disturbance that propagates like waves on water. In nonrelativistic quantum mechanics, the speed of light is considered infinitely large, which is why an illusion of instantaneous change arises.

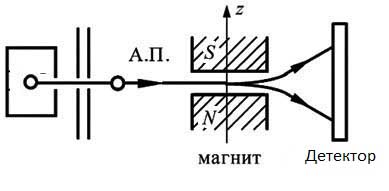

The situation when particles separated by large distances remain coupled in a pair seems paradoxical due to the classical ideas about particles. It must be remembered that there really are not particles, but fields. What we represent as particles are simply the states of these fields. The classical concept of particles is completely unsuitable in the microcosm. Immediately there are questions about the size, shape, material and structure of elementary particles. In fact, situations that are paradoxical for classical thinking also arise with one particle. For example, in the Stern-Gerlach experiment, a hydrogen atom flies through a non-uniform magnetic field directed perpendicularly to velocity. The spin of the nucleus can be neglected due to the smallness of the nuclear magneton, even if the spin of the electron is initially directed along the velocity.

The evolution of the atomic wave function is not difficult to calculate. The initial localized wave packet splits into two identical, flying symmetrically at an angle to the original direction. That is, an atom, a heavy particle, usually regarded as a classical one with a classical trajectory, split into two wave packets, which can fly apart over completely macroscopic distances. At the same time, I note that it follows from the calculation that even the ideal Stern-Gerlach experiment is not able to measure the spin of a particle.

If the detector binds a hydrogen atom, for example, chemically, then the “halves” - two wave packets that have scattered around, are assembled into one. How does such a spreading of a smeared particle occur is a separately existing theory in which I do not understand. Those interested can find extensive literature on this issue.

Conclusion

The question arises - what is the point of numerous experiments on the demonstration of correlations between particles at large distances? In addition to the confirmation of quantum mechanics, which no normal physicist has long doubted, this is a spectacular demonstration that impresses the public and amateur officials who allocate funds for science (for example, the development of quantum communication lines is sponsored by Gazprombank). For physics, these costly demonstrations give nothing, although they allow us to develop the technique of the experiment.

Literature

1. Landau, LD, Lifshits, E.M. Quantum Mechanics (non-relativistic theory). - 3rd edition, revised and enlarged. - M .: Science, 1974. - 752 p. - ("Theoretical Physics", volume III).

2. Eberhard, PH, “Bell's theorem and the different concepts of nonlocality”, Nuovo Cimento 46B, 392-419 (1978)

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/402817/

All Articles