How to swim in a superfluid fluid

As we know, any body floating in a liquid will sooner or later stop due to viscous friction forces, if its movement is not supported by any engine. But there are fluids, called superfluids, in which viscous friction is absent (*) . The most famous example of a superfluid liquid is liquid helium , cooled to at least 2.17 degrees above absolute temperature zero.

Movement in the absence of viscosity manifests itself in many impressive effects: superfluid helium easily flows through the narrowest gaps and cracks, can endlessly flow in a circle (**) and flow out of the vessel through the thinnest liquid film adhering to its walls. All of these phenomena are examples of large-scale quantum effects.

In a recent theoretical article , the question was considered: is it possible to swim in a superfluid liquid? In other words, can a hypothetical swimmer, by moving his arms and legs, create a thrust force that allows him to accelerate or slow down without using the force of viscous friction?

')

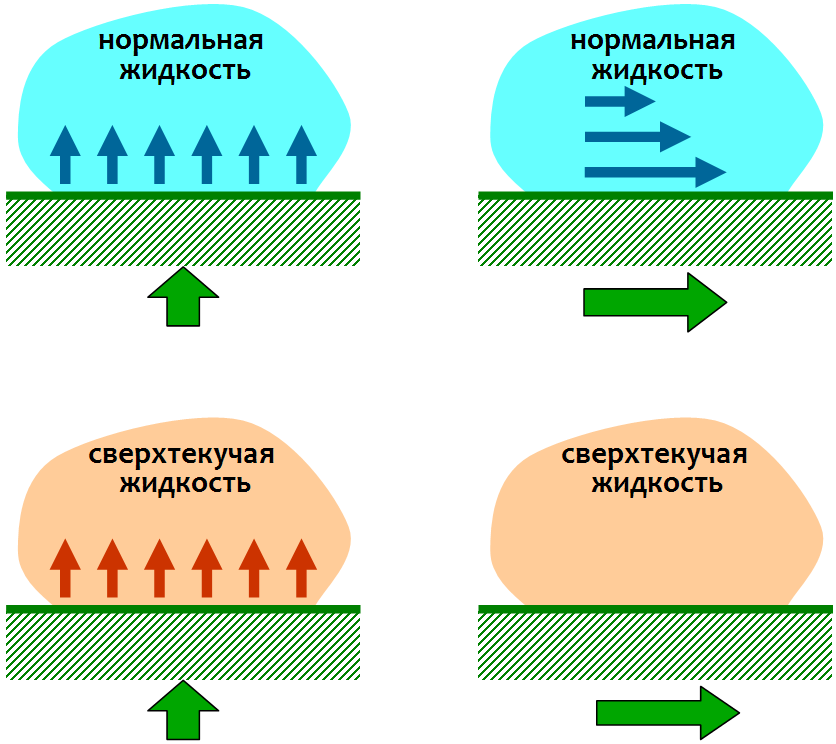

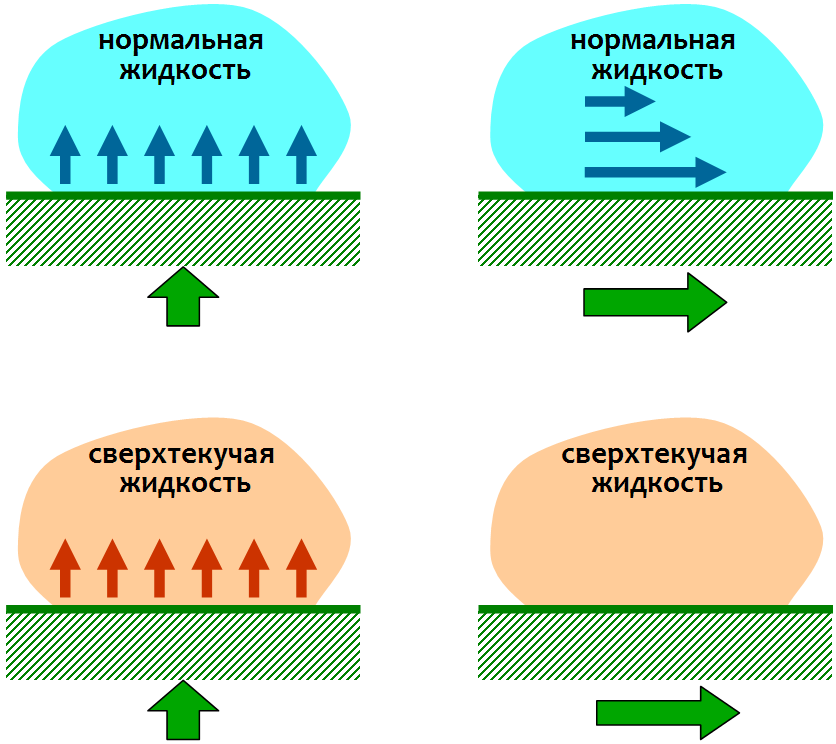

One can realize the non-triviality of the answer to this question by considering the behavior of normal and superfluid liquids when interacting with bodies. As shown in the figure, a normal fluid can be made to move, either by pushing it with a solid surface or by dragging it along with itself due to viscous friction forces. In the superfluid liquid, the latter will not work: there is no friction in it, and it can only be pushed, which, as we shall see, makes some swimming methods impossible.

To analyze the general principles of physical phenomena, it is customary to consider simple models of “spherical horses in a vacuum”. The article under discussion is no exception: it considered two-body and three-body model “swimmers” representing two and three ellipsoids connected by “joints”. Swimmers can move their ellipsoids, bending and straightening their joints. If the swimmer succeeds in repelling the surrounding fluid, he will create a thrust force and start moving.

A two-body swimmer resembles a clam clam and may attempt to swim by periodically changing the angle between its ellipsoids like a butterfly flapping its wings. However, calculations show that he will not be able to swim: when waving, a swimmer moves back and forth, but on average stays in place ( here you can watch a video of his uncomplicated movements).

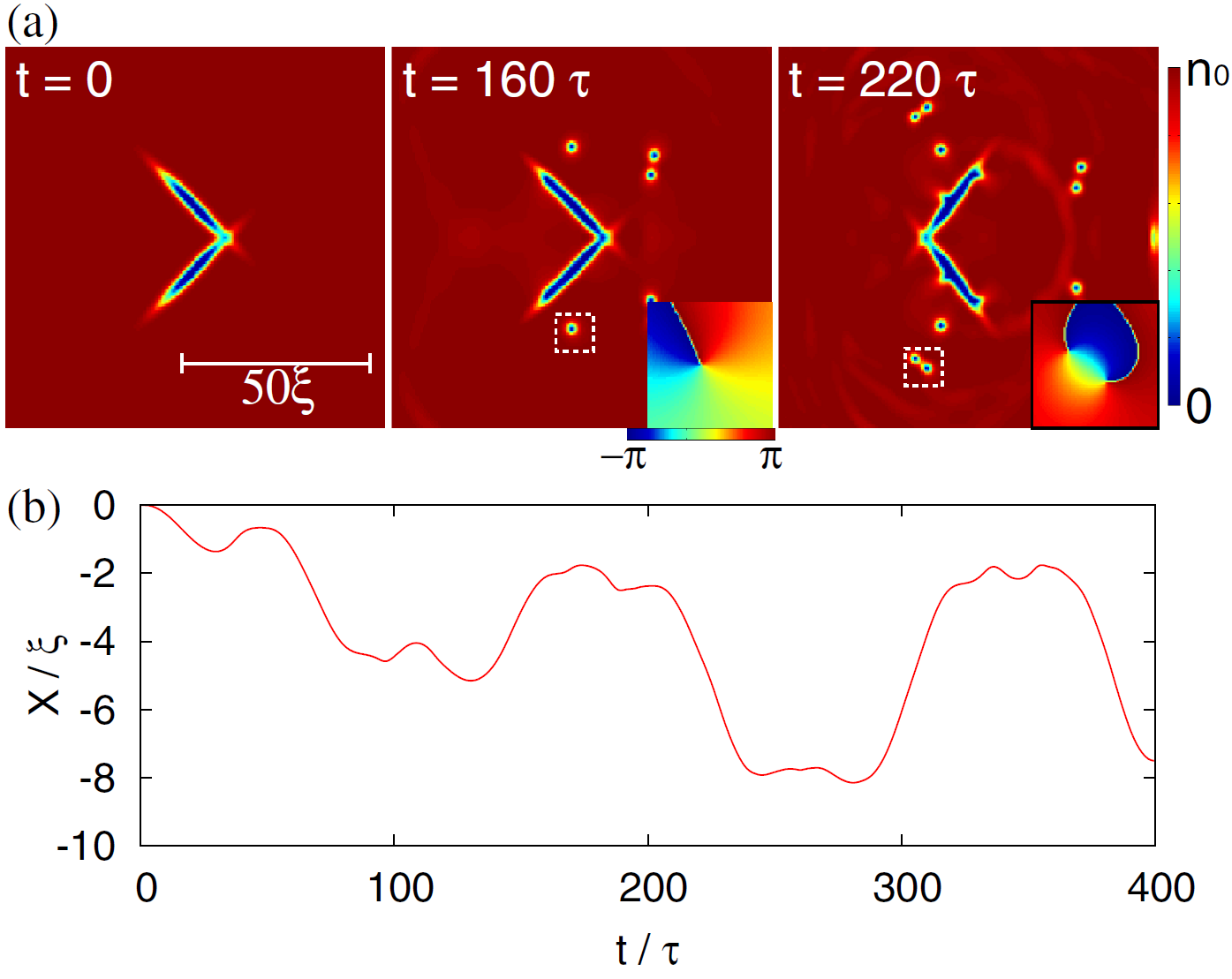

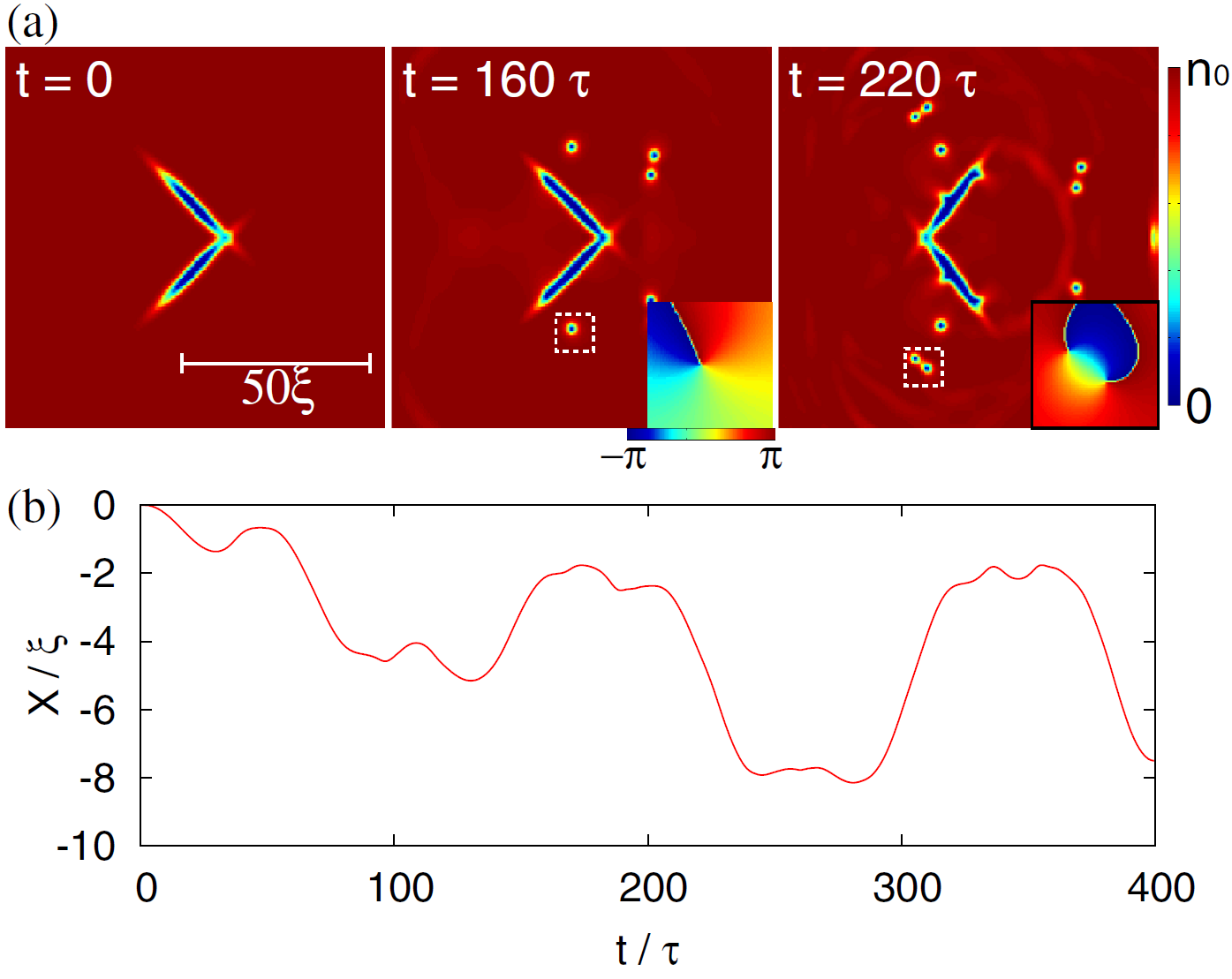

Upstairs: the density profile of a superfluid fluid at different points in time. The blue areas where the fluid is ejected are the ellipsoids of a two-body swimmer.

Below: swimmer's coordinate as a function of time.

Parallels can be drawn between these results and Purcell's scallop theorem . This important theorem of swimming theory says that the bivalve mollusk, which slowly opens and closes its shell in a viscous fluid, will not swim anywhere, since its movements are reversible in time. The latter means that the periodic opening and closing of the shell leaves do not change their appearance when the time starts in the opposite direction (you can imagine a video that looks backward looking just like during normal playback). In our case, the fluid has no viscosity, and it is not the Purcell theorem itself that works, but its counterpart for a superfluid fluid.

Figure from the report of Edward Purcell (Nobel Prize in Physics in 1952).

The situation changes when a two-body swimmer starts waving his ellipsoids with greater frequency. If the speed of their movement exceeds the speed of sound in a liquid, sound waves and vortices (***) start to be emitted. These excitations take with them some momentum, which, due to recoil, forces the swimmer to move. The figure shows that in this case, though its coordinate fluctuates, it generally decreases over time as a whole, which means that the swimmer is moving from right to left. After ten oscillations (to the right of the dotted line on the graph), the flaps of the flaps stop, and the swimmer continues to move by inertia ( video ).

You can try a different type of swimmer movement, when its flaps close and move apart not only in the right direction, but alternately in two directions. Such symmetrical movements are like flapping butterfly wings. Calculations show that in this case many quantized vortices are excited (they are seen in the figure as small circles), but, in general, swimming is not very efficient. The reason is that approximately the same number of vortices are excited, moving both to the right and to the left, and the impulses carried away by them substantially compensate each other ( video ).

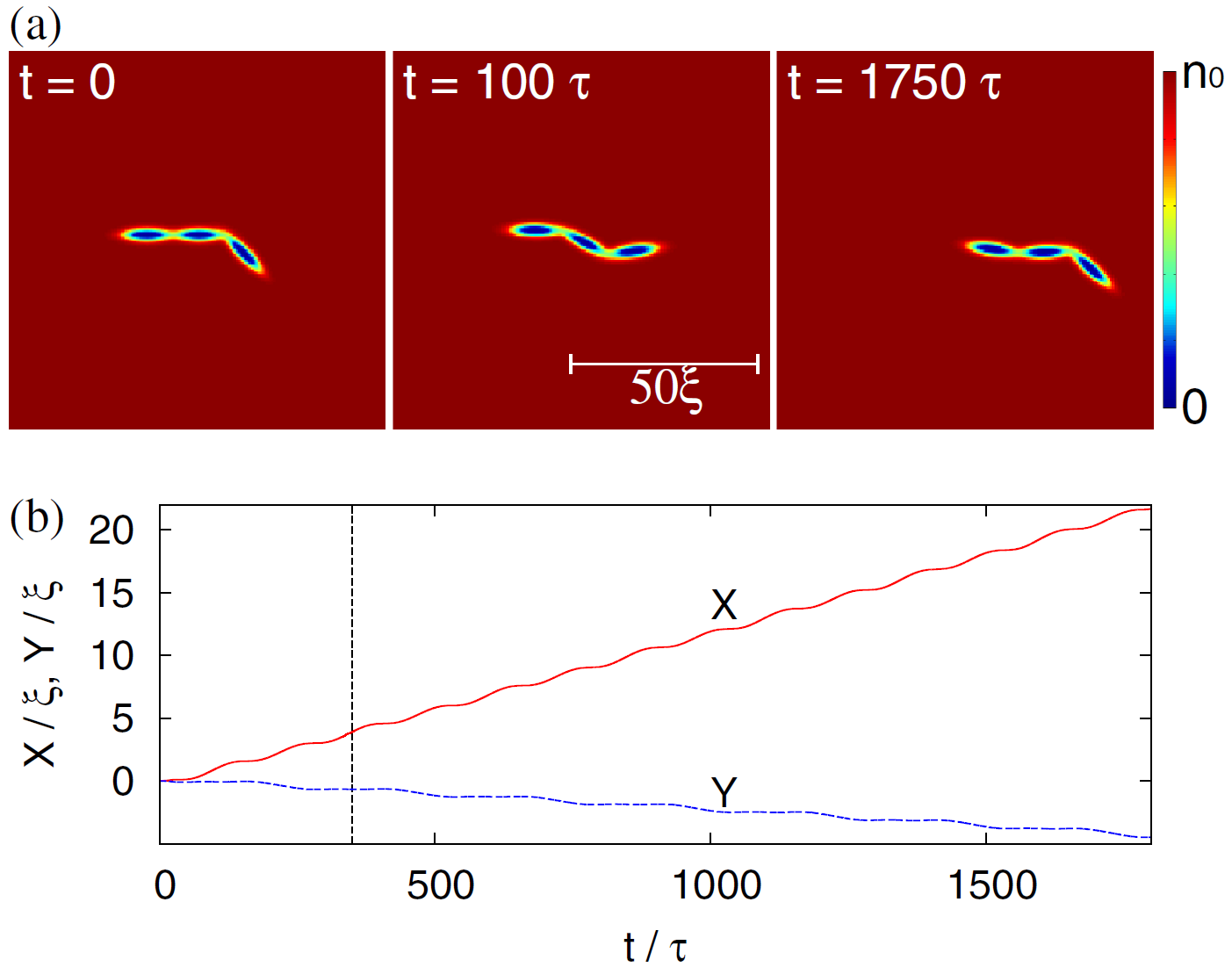

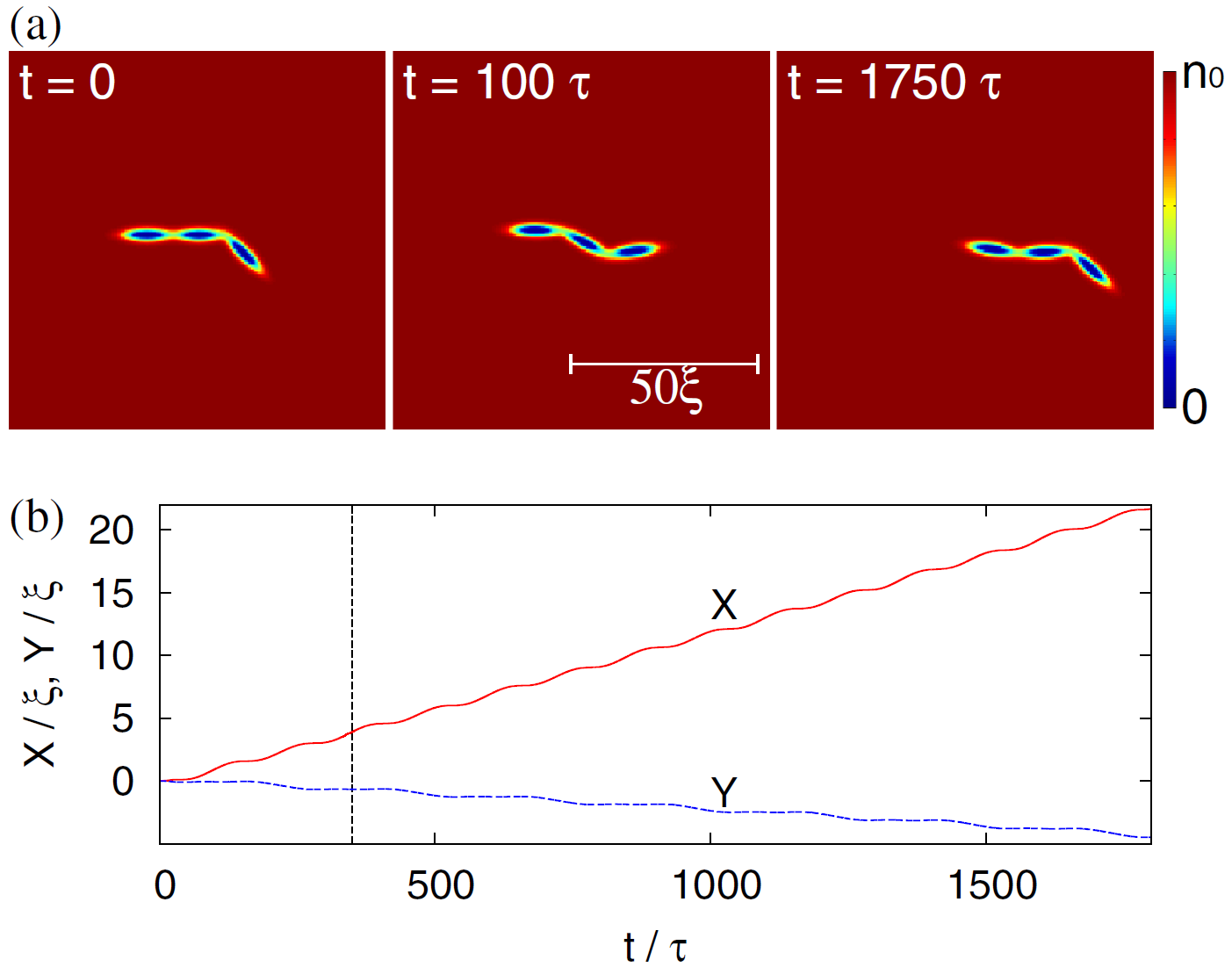

Consider now the three body swimmer. He has an important advantage over a two-body one: he can squirm, making serpentine movements that do not turn into themselves when time is reversed. So, the Purcell theorem is not applicable to it, and it should float even with slow movements. The calculations in the figure confirm this conjecture: with wriggling movements, the swimmer is confidently moving horizontally, while slightly shifting and vertically ( video ).

Upstairs: the density profile of a superfluid fluid at different points in time. The blue areas where the fluid is ejected are the ellipsoids of a three body swimmer.

Below: horizontal (X) and vertical (Y) coordinates of the swimmer as a function of time.

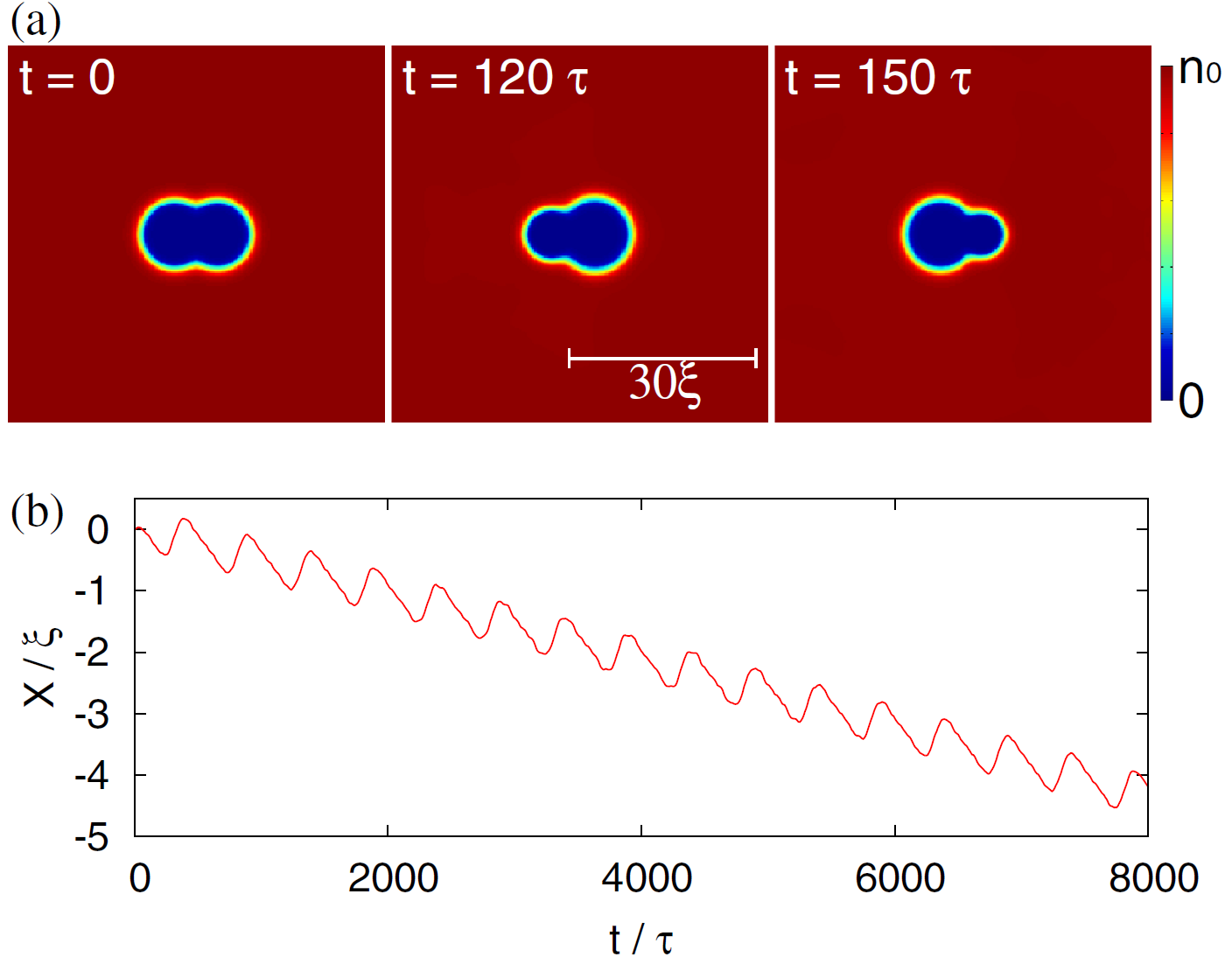

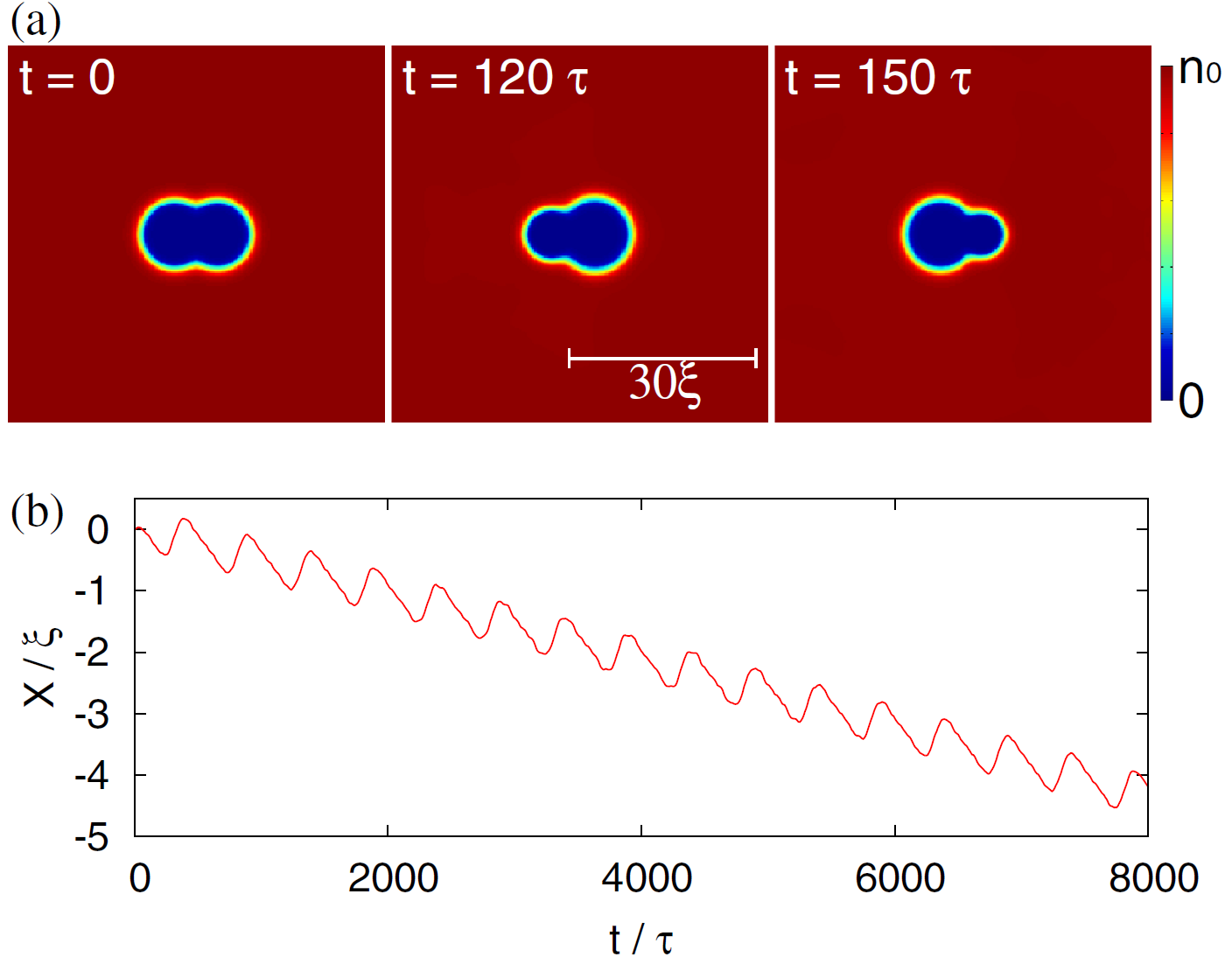

What is the use of the results? It would seem that the problem of swimming in a superfluid liquid is not particularly relevant in practice, but there is one area where it can be useful. Recently, experiments with Bose condensation and the superfluidity of ultracold atomic gases have been actively developed, with which they have big plans for creating quantum simulators, quantum computers and experimental modeling of exotic states of matter. In such systems, you can create bunches of superfluid gas of one type, immersed in superfluid gas of another type. If we can deform the clot the way we need (and this can be done with the help of laser beams), then it will be possible to force this clot to swim, pushing off from the surrounding gas. The figure shows calculations demonstrating this possibility: when changes in the shape of a bunch are not reversible in time, it really manages to move ( video ).

So, we see that you need to swim in a superfluid fluid wisely: Purcell's theorem ensures that we can not swim if our movements with our hands and feet will coincide with ourselves when playing in the opposite direction. To start moving, we will need to either move faster than sound (which is problematic), or wriggle like a snake, violating the reversibility of movement in time. These conclusions are well known to microorganisms floating in a viscous liquid: in order to circumvent the Purcell theorem, they have to use spirally rotating flagella, which are analogs of the three-body swimmer considered here.

According to the article :

Hiroki Saito, Can We Swim in Superfluids ?: Bose – Einstein Constituent, Numerical Demonstration of Self-Propulsion, Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 84, 114001 (2015).

(*) In fact, this is not quite true: any real superfluid liquid can be represented as a combination of a “normal” and superfluid component (a two-fluid model ), and a normal component will still slow down a moving body. However, this does not prevent the superfluid component from moving completely without friction.

(**) In practice, the circular flow of superfluid helium can decay, but not due to viscosity, but due to a quantum mechanical process - the slip of quantized vortices. In the experiments , no noticeable attenuation was observed for 18 hours.

(***) Eddies arising in a superfluid fluid are not just eddies like small tornadoes, but quantized topological excitations . Unlike conventional vortices, they cannot simply disappear due to the gradual attenuation of the flow.

Movement in the absence of viscosity manifests itself in many impressive effects: superfluid helium easily flows through the narrowest gaps and cracks, can endlessly flow in a circle (**) and flow out of the vessel through the thinnest liquid film adhering to its walls. All of these phenomena are examples of large-scale quantum effects.

In a recent theoretical article , the question was considered: is it possible to swim in a superfluid liquid? In other words, can a hypothetical swimmer, by moving his arms and legs, create a thrust force that allows him to accelerate or slow down without using the force of viscous friction?

')

One can realize the non-triviality of the answer to this question by considering the behavior of normal and superfluid liquids when interacting with bodies. As shown in the figure, a normal fluid can be made to move, either by pushing it with a solid surface or by dragging it along with itself due to viscous friction forces. In the superfluid liquid, the latter will not work: there is no friction in it, and it can only be pushed, which, as we shall see, makes some swimming methods impossible.

To analyze the general principles of physical phenomena, it is customary to consider simple models of “spherical horses in a vacuum”. The article under discussion is no exception: it considered two-body and three-body model “swimmers” representing two and three ellipsoids connected by “joints”. Swimmers can move their ellipsoids, bending and straightening their joints. If the swimmer succeeds in repelling the surrounding fluid, he will create a thrust force and start moving.

A two-body swimmer resembles a clam clam and may attempt to swim by periodically changing the angle between its ellipsoids like a butterfly flapping its wings. However, calculations show that he will not be able to swim: when waving, a swimmer moves back and forth, but on average stays in place ( here you can watch a video of his uncomplicated movements).

Upstairs: the density profile of a superfluid fluid at different points in time. The blue areas where the fluid is ejected are the ellipsoids of a two-body swimmer.

Below: swimmer's coordinate as a function of time.

Parallels can be drawn between these results and Purcell's scallop theorem . This important theorem of swimming theory says that the bivalve mollusk, which slowly opens and closes its shell in a viscous fluid, will not swim anywhere, since its movements are reversible in time. The latter means that the periodic opening and closing of the shell leaves do not change their appearance when the time starts in the opposite direction (you can imagine a video that looks backward looking just like during normal playback). In our case, the fluid has no viscosity, and it is not the Purcell theorem itself that works, but its counterpart for a superfluid fluid.

Figure from the report of Edward Purcell (Nobel Prize in Physics in 1952).

The situation changes when a two-body swimmer starts waving his ellipsoids with greater frequency. If the speed of their movement exceeds the speed of sound in a liquid, sound waves and vortices (***) start to be emitted. These excitations take with them some momentum, which, due to recoil, forces the swimmer to move. The figure shows that in this case, though its coordinate fluctuates, it generally decreases over time as a whole, which means that the swimmer is moving from right to left. After ten oscillations (to the right of the dotted line on the graph), the flaps of the flaps stop, and the swimmer continues to move by inertia ( video ).

You can try a different type of swimmer movement, when its flaps close and move apart not only in the right direction, but alternately in two directions. Such symmetrical movements are like flapping butterfly wings. Calculations show that in this case many quantized vortices are excited (they are seen in the figure as small circles), but, in general, swimming is not very efficient. The reason is that approximately the same number of vortices are excited, moving both to the right and to the left, and the impulses carried away by them substantially compensate each other ( video ).

Consider now the three body swimmer. He has an important advantage over a two-body one: he can squirm, making serpentine movements that do not turn into themselves when time is reversed. So, the Purcell theorem is not applicable to it, and it should float even with slow movements. The calculations in the figure confirm this conjecture: with wriggling movements, the swimmer is confidently moving horizontally, while slightly shifting and vertically ( video ).

Upstairs: the density profile of a superfluid fluid at different points in time. The blue areas where the fluid is ejected are the ellipsoids of a three body swimmer.

Below: horizontal (X) and vertical (Y) coordinates of the swimmer as a function of time.

What is the use of the results? It would seem that the problem of swimming in a superfluid liquid is not particularly relevant in practice, but there is one area where it can be useful. Recently, experiments with Bose condensation and the superfluidity of ultracold atomic gases have been actively developed, with which they have big plans for creating quantum simulators, quantum computers and experimental modeling of exotic states of matter. In such systems, you can create bunches of superfluid gas of one type, immersed in superfluid gas of another type. If we can deform the clot the way we need (and this can be done with the help of laser beams), then it will be possible to force this clot to swim, pushing off from the surrounding gas. The figure shows calculations demonstrating this possibility: when changes in the shape of a bunch are not reversible in time, it really manages to move ( video ).

So, we see that you need to swim in a superfluid fluid wisely: Purcell's theorem ensures that we can not swim if our movements with our hands and feet will coincide with ourselves when playing in the opposite direction. To start moving, we will need to either move faster than sound (which is problematic), or wriggle like a snake, violating the reversibility of movement in time. These conclusions are well known to microorganisms floating in a viscous liquid: in order to circumvent the Purcell theorem, they have to use spirally rotating flagella, which are analogs of the three-body swimmer considered here.

According to the article :

Hiroki Saito, Can We Swim in Superfluids ?: Bose – Einstein Constituent, Numerical Demonstration of Self-Propulsion, Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 84, 114001 (2015).

(*) In fact, this is not quite true: any real superfluid liquid can be represented as a combination of a “normal” and superfluid component (a two-fluid model ), and a normal component will still slow down a moving body. However, this does not prevent the superfluid component from moving completely without friction.

(**) In practice, the circular flow of superfluid helium can decay, but not due to viscosity, but due to a quantum mechanical process - the slip of quantized vortices. In the experiments , no noticeable attenuation was observed for 18 hours.

(***) Eddies arising in a superfluid fluid are not just eddies like small tornadoes, but quantized topological excitations . Unlike conventional vortices, they cannot simply disappear due to the gradual attenuation of the flow.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/402663/

All Articles