Peter Watts on the game SOMA

Large spoilers after the image, so stop reading if you are still saving yourself for your own playthrough. (Although, if you still do it a year after the release, then you are even more behind than me.)

From the very beginning of the century, I was ... well, not in a relationship of love or hate for video games, but rather in love and indifference. I worked on several game projects that did not go on sale, wrote a novelization for the released game. Sometimes my work inspired games for which I had nothing to do; for example, the creators of Bioshock 2 and Torment: Tides of Numenera refer to me as an influence. In Witcher 3 there is a vampire named Sarasti. Eclipse Phase is an open source role-playing card game that calls me in its references. And so on.

“If there is life after death, is my place taken? Are the heavens filled with people who will call me an impostor? ”

- Simon Jarrett, realizing that he is a digital copy

For one reason or another, I have never had the opportunity to play these games. But recently, a fan gave me a download of the SOMA game from the Frictional Games, the authors of which also refer to me as the mastermind (along with Greg Egan, Tea Mievil and Philip K. Dick). And in a sudden rush to google myself, I came across various blogs and forums in which people commented on the peculiar Wattsiness (comment similarity to the writer's work) of this particular title. So what the hell, I realized; I had to write something this week, and it would be either SOMA or my impressions of the first acid trip.

In SOMA, you play Simon: an ordinary man from Toronto in 2015 who, after a brain scan at the infamous University of York, suddenly finds himself 100 years in the future, after the cometary blast destroyed all life on Earth. Simon does not need to worry about this, at least not in the short term - because he is not on the surface of the Earth. He is stuck in a complex of abandoned underwater habitats in the middle of a geothermal depression, where (among other things) he is attacked by a giant adder fish, and he finds himself embroiled in history, centered around the nature of consciousness. “I would really like to know who thought of sending a Canadian to the bottom of the sea. Good idea, ”he blurts out at some point. “I miss Toronto. In Toronto, I knew who I was. ”

So yes, I definitely see the influence of Watts. Perhaps even a little respect.

If I felt particularly selfish, I really could have wondered at this character. These subway stations that Simon is traveling on his way to York are not so far from the place where I lived. His friend in the game, Catherine, once mistakenly remarks that he hails from Vancouver, where I lived before. Damn it, if I wanted to use all the possibilities, I could point out that the apostle of Jesus Christ (and the first of the popes) were called Simon Peter. Coincidence?

Yes, probably. This is the last, anyway. Again, any game whose argument in favor of the purchase would have been a reference to Peter Watts would have shot at a rather limited market. Fortunately, the Soma is more meaningful. In fact, it may not be so much inspired by my writing (or Dick, or Egan, or Myvil), since we all draw inspiration from the same frighteningly cool material that underlies human existence. We all drink from one well, we all wake up at night, pursued by the same existential questions: how does the body wake up? Where does subjective awareness come from? What is it to be attacked by a giant viper fish at a depth of four thousand meters?

The effects on SOMA go beyond the usual list of authors that you can find on the Internet (or, for that matter, quotes at the top of this article). Biological cancer, which infects and changes the shape of everything - from people to angler fish - more than resembles the “Melting Plague” in the “Revelation Space” by Aleister Reynolds. And while Simon’s belated discovery that he is actually a digitized scan of the brain, a walking corpse in a suit of armor, may seem to be an attracted element straight from the “nanosuit” in my short story on Crysis 2. In turn, I picked up this idea from Richard Morgan Gameplay

So many details dismantled by the game itself. How does she stitch them together?

Atlantic.

Atlantic.

To begin with - the game is gorgeous in terms of contemplation, and listening to it is insanely creepy. The dregs of the continental shelf, the intermittent darkness of the abyss, the clanks and creaks of the overloaded hull, covering only one side of perception, equally delight and indifference. Of course, these days this is an accurate description for any game that is worth considering. (Alien: Isolation comes to mind - you can practically describe SOMA as an underwater Alien: Isolation with neurophilosophical content). SOMA technologies seem oddly outdated for the 22nd century - flickering fluorescent lights, video cameras from the 70s, desktop computers that look much less advanced than the latest offerings on Staples - but this is also true for many games these days. (This time we skip Alien: Isolation, because it honors the aesthetics of the film. The Deus Ex franchise suits, to some extent)

The only battle scene in the game is to attack the robot with a shocker.

The only battle scene in the game is to attack the robot with a shocker.

The interface does not interfere too much with the view, there are no hit points or health icons that clutter the edges of the screen. You will learn that you were injured when your eyesight is blurred and you can no longer run. You have no tracking weapon. Inventory options are generally a joke: approximately 90% of the game, you are absolutely empty-handed, with the exception of the vaunted door opener, which helps to go further. This is the most minimalistic approach to the interface than other representatives, and so much the better.

Your work tool.

Your work tool.

There are no dialogue options in the same way. From time to time you can start a conversation, but from now on, by and large, you are listening to the radio. I believe that Frictional Games have made the right choice here. All of these awkward dialog menus that appear in Fallout or Mass Effect — the same four or five options that are served time after time, regardless of context (Really? Do I want to ask right now about our relationship with Piper?) —Require enough flexibility in conversations, but only to emphasize how insignificant you have flexibility in this very communication. This is one of the inherent weaknesses of computer games as an art form - gaming technology is not sufficiently developed to improvise a decent dialogue on the fly.

SOMA cuts a player from this cycle during conversational periods. The price of this is that we lose the illusion of control (which is actually a metaphor if you think about it). The advantage is that we end up with more intense dialogues, elaborate characters, shock and tantrum, and an emotional investment that goes along with a mental experiment. Simon is not some empty vessel so that the player can fill it with him; he is a lively character himself.

I agree that he is not the most gifted. At some point, he mentions that he used to work in a bookstore, but considering how long it takes him to catch certain things, I can bet that in his store bookshelves with scientific and popular fiction were pretty shitty . Simon is a good guy, and I really like him, but if his hometown was written off from mine, then I can only pin hopes, which cannot be said about his intellect either.

On the other hand, who can say that I would be more intelligent if I were a dusty photocopy of a long-dead brain, without any warning thrown into the Apocalypse? I do not know who, under these conditions, would turn all the synapses to its fullest; In addition, the sluggish pace at which Simon comprehends the essence provides a convenient opportunity to bring to consciousness some philosophical problems that many players have not thought about before. The fact that a friend of Simon is more and more impatient with his "nonsense", so that she has to re-play herself every time - suggests that this was a deliberate decision on the part of Frictional Games.

But if Simon hesitated a little, then SOMA did not. Even landscapes are smart. Wandering across the seabed at a depth of several hundred to four thousand meters, the fauna looks believable: sea spiders, fishes of the family of the makrarus, tiny bioluminescent squid and tubular worms, and rainbow-colored, magnificent ctenophores. (Combs! How many of you know what it is?). In one of the habitats, in the laboratory notes of the deceased scientist, there are observations on how to observe the Haulyod (“viper fish” for you, the bushmen): “usually does not occur at such a depth — probably an anomaly”. When I read it, I shed a little tears. When writing Starfish in the 90s, I also had to contend with the fact that the adder fish does not swim away into a deep abyss. I had to invent my own explanation of why they swam to the north-western side of the submarine volcano Aksial.

Cute little fish

Cute little fish

No matter how smart or stupid the ocean is, it just acts as a setting. The story of SOMA revolves around the problems of consciousness. Frictional Games have done their homework here. Undoubtedly, the game has the usual disposable elements, for example - the model of a reasonable drone "Qualia-class". But things like “body exchange” and “rubber hand illusions” are not just for show. They actively give life to the elements of the plot. People walk with “black boxes” in their brains that can be read for data after death. (This proves usefulness in ascertaining the background of SOMA — a rather inventive twist in conventional mechanics called “let's find personal diaries that are scattered everywhere” that is used in such games). Most of the key events in this story do not occur in order to influence the course of the plot, but in order to make you think about its main themes.

For comparison, look at Bioshock - the spiritual brother of SOMA. With all of his explicit references to the ideology of Ayn Rand, he fails as an analysis. (At best, its analysis is that objectivism is bad, because capitalism loses power over itself when genetically modified mollusks lead to widespread insanity, and the ability to shoot living bees from your hands). The political beliefs of Andrew Ryan serve only as a background for the ongoing action, and as a poster justification of the setting; but the events of history could just as easily have happened in a failed socialist utopia as in a capitalist utopia. Bioshock was brilliant in how to use the mechanics of the game, he reported one of his themes (in this respect, I did not see anything of the kind), but this particular topic revolved around the existence of free will without a significant connection with the ideology of objectivism. On the contrary, the SOMA actually faces the problems that it presents; she makes them part of the plot.

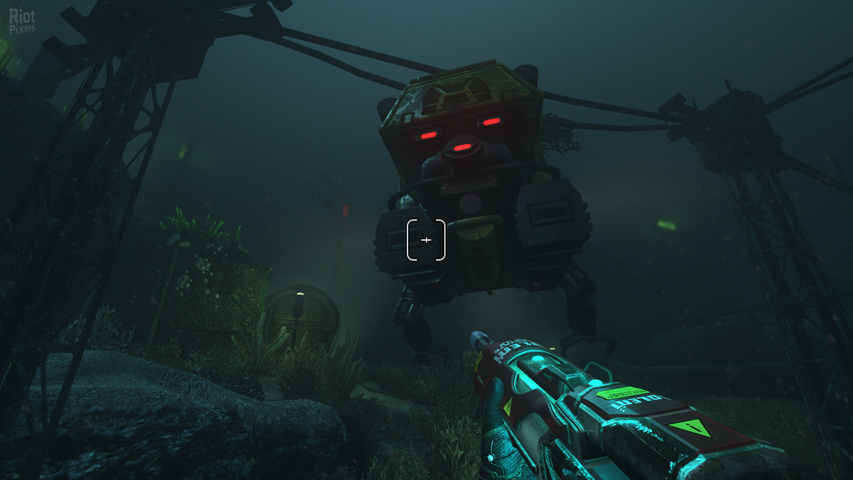

Of course, you can argue that SOMA is more a reflection than a game, an extended scenario that systematically builds up the inevitable nihilistic conclusion (actually two conclusions; the second looks brighter and happier than the first, but in fact depressed, if not ceasing to think about it). If there is a problem with this game, then it lies in the fact that the story in it is so dense, and the thinking is so linear that it does not allow players to be given a lot of freedom for fear of spoiling the script. So there is only one way to play SOMA. Discoveries and revelations occur in a certain order, conversations occur accordingly. Mandatory monsters justified as unsuccessful prototypes — created by artificial intelligence trying to create Humanity 2.0 — are in fact nothing for history. You can't even kill them. You can not talk to them. You can not rob their corpses for the sake of trophies, or create a homemade cannon from their remains, to blow them up the fuck. Your interactive options consist solely of running and hiding. Monsters in the game do not pursue any real goal, except to suddenly sneak up on you, and slow down your progress along the narrative monorail.

Of course, you can argue that SOMA is more a reflection than a game, an extended scenario that systematically builds up the inevitable nihilistic conclusion (actually two conclusions; the second looks brighter and happier than the first, but in fact depressed, if not ceasing to think about it). If there is a problem with this game, then it lies in the fact that the story in it is so dense, and the thinking is so linear that it does not allow players to be given a lot of freedom for fear of spoiling the script. So there is only one way to play SOMA. Discoveries and revelations occur in a certain order, conversations occur accordingly. Mandatory monsters justified as unsuccessful prototypes — created by artificial intelligence trying to create Humanity 2.0 — are in fact nothing for history. You can't even kill them. You can not talk to them. You can not rob their corpses for the sake of trophies, or create a homemade cannon from their remains, to blow them up the fuck. Your interactive options consist solely of running and hiding. Monsters in the game do not pursue any real goal, except to suddenly sneak up on you, and slow down your progress along the narrative monorail.

There are choices that need to be made - surprisingly affecting them - but they do not affect the outcome of the plot. Your reaction to the last surviving person. It languishes in a flickering dim room at the bottom of the sea. The intravenous needle festers in her hand, photographs of her beloved Greenland (which is now buried with everything else), are scattered around the deck - who would not want to die in such layouts. Re-activation and interrogation of the alarmist who does not know that he is digitized (although I am sure that some kind of crap is happening), and you turn it off after you receive the necessary information from him. Processing your own previous iterations, which were inconveniently preserved after your transcription into a new body.

In principle, it is easy enough to justify such creative decisions; in practice, the result looks like a hoax. I spent half an hour, walking on the seabed, in search of a specific object among the wreckage - a computer chip - it would save me from having to kill a sensible drone for the sake of the same vital part. Frictional Games cost nothing to give me this option; they have already littered the seabed with broken drones, so there would be no need to kill them, so that they would leave me a useful trophy. But no. The only way out is to kill an innocent creature. This has definitely created a philosophical meaning, but it feels somehow wrong. Forced.

Usually this is the point at which I start grumbling, that it would be nice for all the “inspired” game developers who ascribe to me, once inspired to hire me, instead of just getting my stories. It would be completely useless to whimper - I already confessed to the game geeks about my past at the beginning of this post, but I still pokhnichu. Come on - if one of your masterminds is sitting in a corner opposite a pot with a philodendron, then why not ask him about the dance? Maybe he can teach you a couple of new movements.

However, this time I'm going to restrain myself. SOMA could not be an easy task; I could complain about the limitations of linear gameplay or the intermittent obscurantism of the protagonist, but given the limitations of the environment, I do not know if I could have done something better without sacrificing mission priority. SOMA is a straightforward survival-horror style game, but the horror is more existential than external. And the usual mechanics are great serve the main topic, which I had never met in a video game.

To summarize, I think they did a damn good job.

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/402639/

All Articles