The power of natural networks is in excess loops

Looped networks are often found in nature - for example, in the veins of the sacred ficus leaf

Look at the thin branching patterns on a leaf of a tree or a dragonfly wing, and you will see complex networks consisting of nested loops. Such patterns can be found everywhere, both in nature and in man-made structures: in the vascular network of the brain, in the mycelium, in the tangled form of a feeding slimewick, and in the metal ramifications of the Eiffel Tower.

')

The network architecture, including loops — such as redundant computer networks or electrical networks — makes it resilient to damage. Marcelo Magnasco, a physicist at Rockefeller University, points out that the Eiffel Tower is an obvious example of a structure containing loops designed to distribute the load as evenly as possible across its recursive frame. It is surprising that we know so little about why the nets in the leaves or the cortical blood vessels are organized in the same way.

Looped nets in dragonfly wings make them resistant to damage.

“We know a lot about the physics of the connections between entities, to an aversion,” says Magnasko of simple circulatory systems. - And, nevertheless, we do not understand the system as a whole. We do not know why they look like this or why each tree is different from the rest. ”

Over the past few years, Magnasco and other scientists have begun to investigate the reason why such patterns are very often found in nature. Studies of the leaves and blood supply to the brain have confirmed that nested loops create a damage resistant structure that can cope with fluctuations in fluid flow. Now scientists are beginning to numerically evaluate the properties of these networks, to get an idea of their main characteristics, such as stability, and also to figure out how to compare these networks as informative as possible.

“Plants are impressive systems for physical research because they are mathematically beautiful,” says Eleni Katifori , a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization, working in conjunction with Magnasco. According to her, plants grow iteratively and often exhibit a structure similar to crystals, which can be found in such examples as cones or a flower of a sunflower. "We hope that by understanding the vein architecture, we will better understand the photosynthetic efficiency of plants."

Understanding the structure of the veins can shed light on the much more complex blood system of the brain surface, and help to understand the relationship between brain activity and blood flow. This connection is still not clear, but thanks to it, it is possible to carry out functional magnetic resonance imaging, one of the most popular methods for obtaining images of the brain.

The markup of these networks can help identify parts of the brain that are particularly susceptible to strokes, as well as understand the role of blood flow in Alzheimer's disease and other cognitive diseases. “Imagine how we look at the diseased brain and are trying to determine if any of these fundamental parameters have changed and how this can be related to the development of the disease,” said David Boas , a physicist at the Massachusetts Hospital in Boston.

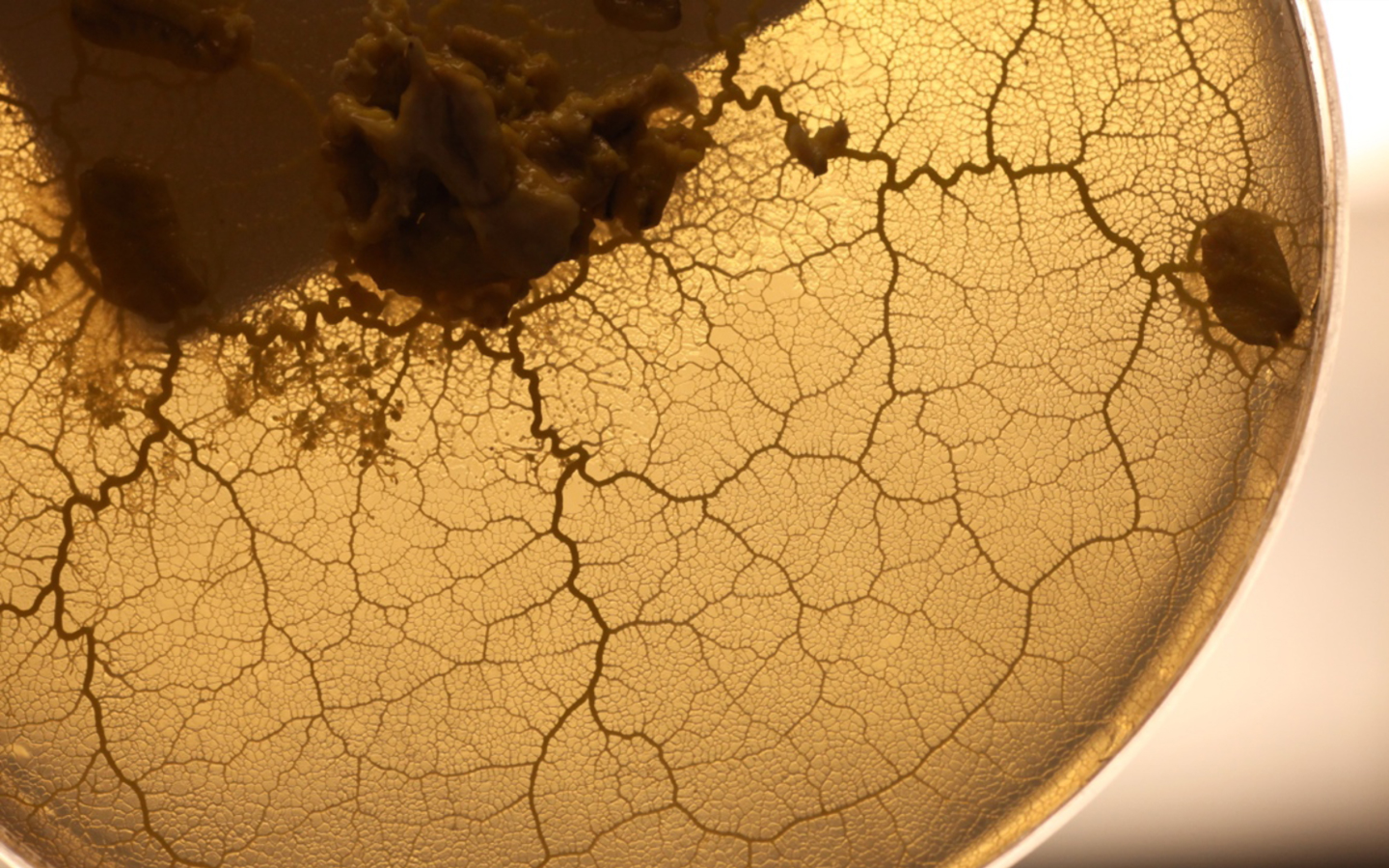

Physarum polycephalum slimeevik forms looped nets when searching for food

Since circulatory systems can be represented as a network of connected tubes, and fluid flows can be calculated due to long-known equations, physicists can quite easily simulate such simple networks as streaks on tree leaves. Studying such systems, Magnasco hopes to understand why veins have exactly such size and angles of connection, and how structures of different scales work together in a network.

Magnasko says that network analysis methods, which are easy to visualize, can then be applied to biological networks that are more difficult to model — say, the cobwebs of genes and proteins, or neural networks of the brain. The leaves are “a good object of research, since they do not have the difficulties inherent in other networks,” says Magnasco.

How to build a sheet

When the need arises to build an effective network, evolution needs to consider two factors: the cost of building and the cost of network operation. In the case of vessels, this means the cost of creating veins and pumping fluids through them. It is cheaper to operate with a simple tree structure, which can be found in ancient plants. This structure, although effective, is not very stable. If the connection is damaged, a part of the system suffers from fluid loss and dies .

To understand the topology of the vein architecture, Katifori and Magnasko built a simple network model, trying to understand its basic properties . They simulated the veinlets (xylem) in the form of a network of pipes with different pressure and flow. They tried to answer the question, how, with a limited number of pipes, should they be distributed in order to minimize the pressure drop and make the system as resistant as possible to damage? In the real world, "the leaf, from which a piece of an insect has bitten off, continues to function," says Katifori.

They found that the architecture of hierarchically nested loops — that is, the loops inside the loops inside the loops — is more resistant to damage than the others. “Loops add redundancy to the network,” says Kathiori. "In the event of damage, water can be redirected through other channels." The structures produced by the model published in the journal PLoS ONE look very similar to some leaves.

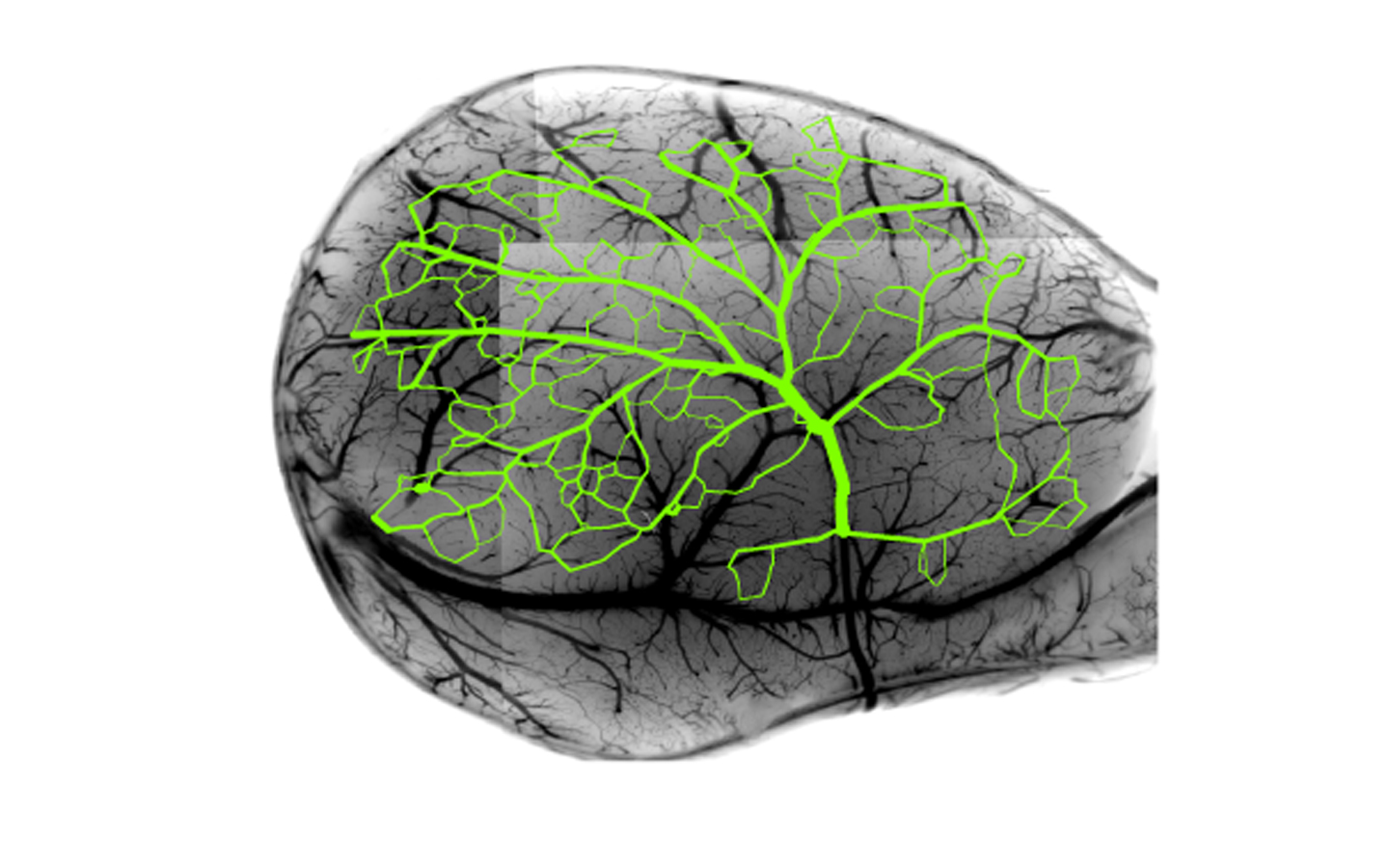

Blood vessels on the surface of the cortex of the rodent form looped nets, which allows blood to quickly reach any part even after a little damage.

Amazing shots of fluorescent fluid flowing through damaged leaves helped researchers to quantify how water flows around the site of damage. The ginkgo biloba leaf (Ginkgo bilŏba), an evolutionarily ancient plant with a tree-like, rather than looped, structure, cannot boast of such endurance.

The researchers also found that looped networks cope better with fluctuations in fluid circulation when environmental conditions change.

Now Katifori and Mgnasko model adaptive looped networks that evolve in response to changing conditions. Such processes can occur in fungi, some types of mold, and even in the developing circulatory system of animals. For example, the slyzhevik in search of food constantly changes shape, pulls out long fingers, often in the form of looped nets. In one surprising experiment, Japanese researchers raised a slyshevik on a surface dotted with oatmeal scattered around cities in Tokyo. As a result, the slug tank grew into a looped network resembling an efficient system of city railways.

Blood vessel markup

Effective blood circulation is necessary for the functioning of the brain, which does not have mechanisms for energy conservation: electrically active neurons must be rapidly fed. As a result, the brain is engaged in precise adjustment of blood flow and increases blood delivery to areas in need. “This precise adjustment of the blood flow is very local, much smaller than millimeter in size,” says Bruno Weber , a neuroscientist at the University of Zurich.

More than ten years ago, Daffyd Kleinfield , a physicist and neuroscientist at the University of California at San Diego, and his colleagues discovered that they were able to track the blood circulation in the individual brain capillaries of rodents. They found that the bloodstream sometimes changes direction to the opposite, which speaks in favor of the looped structure of the vessels. “There was a hint that the circulatory system would be more interesting than I thought at first,” says Kleinfield.

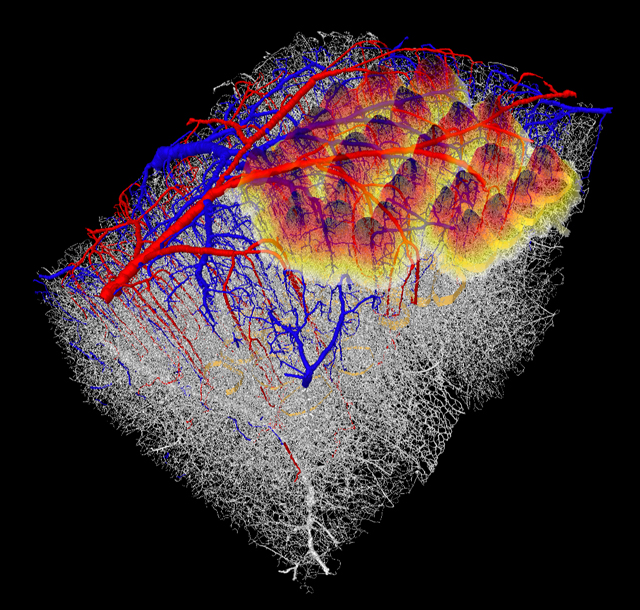

On the map of the vessels in the cortex of the rodent's brain, the network is obsessed. It also shows that the architecture of the blood vessels does not correspond to neuroanatomy (yellow and orange cones)

A few years ago, the Kleinfield team discovered that the superficial circulatory system of the somatosensory cortex, a part of the brain that is activated at the moment when the animal uses its whiskers for orientation in space, is organized into randomly arranged interlocking loops . This allows the blood to approach a particular site from all directions, which provides the necessary neurons for feeding. “If the loops are randomly connected to a two-dimensional lattice, the blood can approach the electrically active region radially,” says Kleinfield.

In 2010, researchers labeled a network of blood vessels covering the surface of the neocortex in rats and mice, the outer layer of the cerebral cortex. “We guessed that it forms a mesh network, so we filled the circulatory system and marked the surface,” says Kleinfield. "Most of the vessels formed a loopback architecture." Scientists suspect that the network has some level of redundancy, but the Kleinfield team has reached a new level of detail. “We were the first to mark everything entirely and came close to the topology - in order to numerically describe the network and use this for calculating the flows,” says Kleinfield.

The Delta of the Ganges forms a tangled looped network.

The researchers used this connectivity map to simulate a situation in which one vessel of the network is blocked. Both in the model and in the real brain, blocking the vessel in a two-dimensional grid did not have a special effect. The blood simply flows through other vessels. This discovery is confirmed by clinical practice: strokes never occur on the surface of the brain. "We think this is because it is so arranged," says Kleinfield.

Then Kleinfield and his colleagues went to the depths of the brain, studying the network of blood vessels that feed the neurons of the somatosensory cortex. In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience, researchers have shown that capillaries form a continuous network. “This means that microvessels, capillaries, are mutually connected with each other,” says Kleinfield. “There are no plots with isolated vessels, that is, closed cottage settlements, if we use analogies with real estate.”

The researchers used an approach to statistical mechanisms called “graph theory” to find out why vessels form networks in which exactly three edges meet at each vertex — this was previously observed in the laboratory (vessels play the role of ribs). Kleinfield's colleague, physicist Harry Suhl of the University of California at San Diego, showed that such a scheme is particularly stable. “Especially in comparison with graphs, in which the number of edges to the top is not fixed, as it happens on the Internet,” says Kleinfield.

As in the case of the superficial network, blocking the blood flow in the capillaries has virtually no effect on the operation of the network - blood just goes the other way. However, blocking a penetrating vessel from the surface of the cortex into the brain occurs with serious consequences. The blood flow is blocked, and the brain tissue surrounding this place is dying off. Penetrating vessels are susceptible to blocking, since they do not form loops, but Kleinfield suspects that the architecture provides effective ways to redistribute blood along certain paths in the brain.

Cycled nets are also found in marine animals, for example, this gorgonian coral

What this means clinically is unclear. Neuroscientists do not report on strokes due to blockage of penetrating vessels, but this is only because the vessels are too small to be viewed using conventional imaging devices, and it is unlikely that they can cause symptoms alone. However, Geert Jan Biessels , a neuroscientist at the University Medical Center in Utrecht, says new, more powerful imaging technologies for the brain make it possible to detect very little damage, although not yet with such a resolution to see individual penetrating vessels. . He adds that autopsy data shows that such micro-strokes "can be an important sign of cognitive decline and dementia several years before death."

Loops in the brain

Having acquired new tools for marking the circulatory system of the brain, the Kleinfield team plans to study how the brain's circulatory system differs in rodents with certain mutations, or from other species. “Now we can start exploring different blood systems and determine why they are what they are,” says Kleinfield.

A preliminary study of mice without a protein responsible for oxygen recognition reveals radically altered structures: unlike ordinary animals, mutant mice do not have a two-dimensional network of vessels on the surface of the brain. “There is only a three-dimensional structure,” says Kleinfield. “It's like a Rube Goldberg machine , made up of small tubes.”

Weber and Kleinfield are working together on a project to mark the entire circulatory system in the mouse brain, funded by the European project The Human Brain Project [ The Human Brain Project ]. Weber says that this map will allow building more accurate models and will provide the basis for achieving the goal of building a complete brain map. It will also allow researchers to find out if certain parts of the brain are subject to strokes (for example, the striatum , which is engaged in motor planning) because of the weak interconnection of their circulatory system.

Researchers are also starting to study the circulatory systems of other parts of the body. Lance Mann [Lance Munn], a biologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, says that in most tissues there is significant redundancy in the form of loops. “For example, in the skin, these loops provide alternative paths for blood in the event of damage — blood can“ go around ”the area to get to the tissue“ downstream ”relative to the damaged vessels, he says. Man studies the properties of blood vessels in tumors, which grows in a developed network of vessels that feed cancerous tissue. A popular class of drugs, angiogenic inhibitors , stop the growth of tumors, interfering with the formation of new blood vessels.

Kleinfield uses tools designed to study the circulatory networks to study neural networks in the brain stem , such as sensorimotor loops that control the movement of the whiskers in mice and the acquisition of information. Although "the circulatory systems themselves are interesting," says Kleinfield, they also serve as "warm-up for studying the nervous system."

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/402253/

All Articles