Unexpected reason for the existence of complex life forms

Charles Darwin was not even 30 when he had already managed to form the basis of the theory of evolution. But he only revealed his reasoning to the world after he turned 50. For two decades, he methodically collected evidence for his theory and came up with answers to all the skeptical counterarguments he could imagine. And the most anticipated counter-argument was that a gradual evolutionary process could not lead to the emergence of certain complex structures.

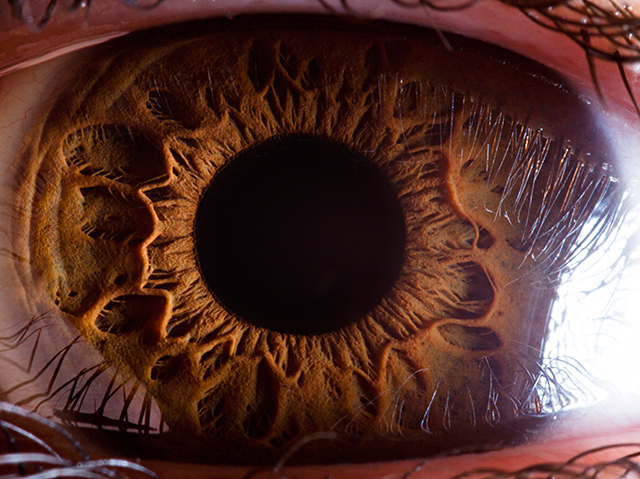

Take the human eye. It consists of many parts - the retina, lens, muscle, jelly, etc. - and they all must interact to ensure vision. Damage one piece and this can lead to blindness. The eye works only if all its parts have the necessary size and shape in order to work together. If Darwin was right, then the complex eye evolved from simpler predecessors. In The Origin of Species, Darwin wrote that this idea "seems, and I openly admit, to be incredibly absurd."

But Darwin was able to see the path to the evolution of complexity. In each generation, the properties of individuals differed. Some variants increased their survival rate and allowed them to leave more offspring. Through generations, these advantages became more common - that is, were "selected." Appearing and spreading, new variants could be played with anatomy and generate complex structures.

Darwin argued that the human eye could evolve from a simple piece of tissue that responds to light, such as today's flatworms. Natural selection could turn this area into a recess capable of recognizing the direction of light. Then, the additional property would work further out, adapting the organism to the surrounding conditions, and this intermediate ancestor of the eye would be passed on to subsequent generations. Step by step, natural selection would increase complexity, since each intermediate form would have an advantage over the previous one.

')

Darwin's reasoning about the origin of complexity found support in modern biology. Today, biologists can examine the eye and other organs in detail, and at the molecular level find extremely complex proteins that come together to form structures that are remarkably similar to conveyor belts, motors, and valves. Such sophisticated protein systems could have come from simpler ones, when natural selection played in favor of intermediate variants.

But lately, some scientists and philosophers have suggested that complexity may appear in other ways. Some argue that life tends to become complicated over time. Others suggest that in the process of the occurrence of random mutations, complexity is a side effect, even without the help of natural selection. They say that complexity is not only the result of millions of years of fine adjustment through natural selection, a process that Richard Dawkins called a “blind watchmaker.” We can say that it just happens.

Sum of changeable parts

For decades biologists and philosophers have been contemplating the evolution of complex structures, but according to Daniel W. McShea, a paleobiologist at Duke University, they were hampered by the vagueness of definitions. “The problem is not only that they do not know how to evaluate it numerically. They do not know what they mean by this word, ”says Makshi.

Makshi has been working on this issue for several years with Robert N. Brandon at Duke University. Makshi and Brandon suggest paying attention not only to the number of parts that make up the organisms, but also to the types of these parts. Our bodies consist of 10 trillion cells. If they were all of the same type, we would be devoid of characteristic features in piles of protoplasm. Instead, we have muscle cells, red blood cells, skin cells, and the like. Even in the same organ, there can be different types of cells. The retina has 60 different types of neurons, each of which performs its own task. This approach allows us to state that people are definitely more difficult than an animal like a sponge, which has only six types of cells.

One of the advantages of this definition is the ability to measure complexity in several ways. In our skeletons there are different types of bones, each of which has a certain shape. Even the spine consists of various parts, from the vertebrae in the neck that hold the head, to those that support the rib cage.

In their 2010 book, Biology's First Law, Biqi's and Brandon described the way in which complex structures could be created that way. They argue that several parts, more or less similar to the start, should begin to differ over time. In the reproduction of organisms, one or more of their genes can mutate. Sometimes, due to mutations, new types of parts appear. If the organism has more constituent parts, they have the opportunity to begin to differ. After accidentally copying a gene, its duplicate may pick up mutations that are missing from the original gene. So, starting with a set of identical parts, you can see how they gradually begin to differ more and more from each other. That is, the complexity of the body increases.

Increasing complexity can help the body survive better, or leave more offspring. In this case, natural selection will pick up this trend and spread it across the population. For example, in mammals, sense of smell works by binding odor molecules to receptors on the nerve endings in the nose. The receptor genes have been constantly duplicated for millions of years. Newer copies mutate and allow mammals to smell more flavors. Animals that rely on scent, such as mice and dogs, have more than 1000 genes for these receptors. On the other hand, complexity can be a burden. Mutations can, for example, change the shape of the vertebrae, making it difficult to turn the head. Natural selection will keep these mutations from spreading by population. Organisms that are born with such properties will usually die before reproduction, and thereby remove harmful properties from circulation. In these cases, natural selection works against complexity.

In contrast to the conventional theory of evolution, in the theory of Makshi and Brandon, an increase in complexity is observed even in the absence of natural selection. They consider this a fundamental law of biology - perhaps the only one. They called it the law of the evolution of zero force.

Drosophila Testing

Recently, Makshi and Leonore Fleming, a graduate student at Duke University, tested the law of the evolution of zero power. The test subjects were flies-Drosophila. For more than a hundred years, scientists have grown flocks of such flies for use in experiments. In laboratory homes, flies lead a pampered life; they have a constant source of food and an even, warm climate. Their wild relatives have to contend with starvation, predators, cold and heat. Natural selection actively interferes with the life of wild flies, eliminating mutations that do not allow them to cope with their many trials. In a protected environment of laboratories, natural selection is very weak.

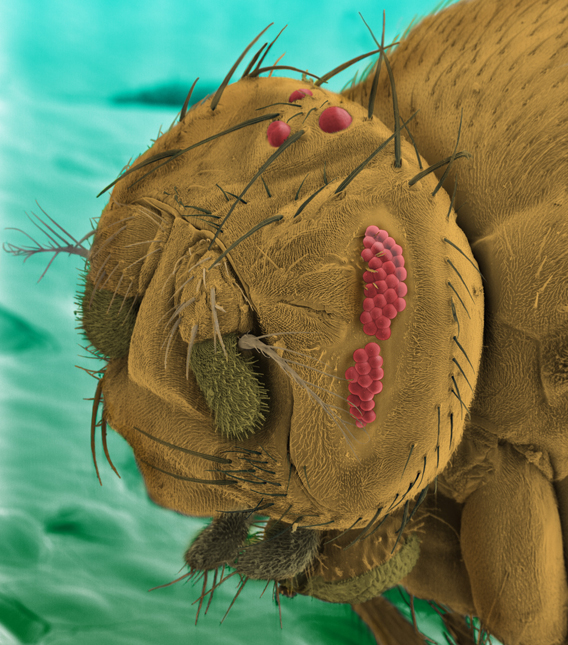

Laboratory fruit flies are more complicated than wild ones, since even unsuccessful mutations spread in a protected environment. This fly has eyes in the form of rectangles,

less than ordinary flies.

The law of the evolution of zero power gives a clear prediction: over the past hundred years, laboratory flies have been subjected to a weaker elimination of adverse mutations, and therefore they had to become more complex than wild ones.

Fleming and Makshi studied the scientific literature on 916 pedigrees of laboratory flies. They conducted many measurements of the complexity of each population. Recently, in Evolution & Development magazine, they reported that laboratory flies were indeed more difficult than wild ones.

Although some biologists support the zero-force evolution law, Douglas Erwin, a leading paleontologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, believes he has serious flaws. "One of his main assumptions does not work," he said. According to the law, complexity may increase in the absence of selection. But this would only be the case if organisms could exist outside the influence of selection. In real life, even if they are cared for blindly adored by scientists, the selection still works. In order for an animal such as a fly to develop properly, hundreds of genes must interact in a complex system, turning one cell into a multitude, growing various organs, etc. Mutations can interfere with this choreography and prevent flies from growing into viable adults.

An organism can exist without external selection - without the environment determining who won and who lost in the evolutionary race - but it will still undergo an internal selection that takes place inside the organisms. Erwin believes that in the new work, Makshi and Fleming do not provide evidence of their law, since "they only consider adult options." The researchers do not take into account the mutants who died from developmental disorders before reaching maturity, despite the departure from scientists.

Some insects have uneven legs. Others have complicated patterns on the wings. The shape of their antenna segments is changing. Freed from natural selection, they cleared their difficulties.

Another objection from Erwin and other critics is that the complexity option from Makshi and Brandon does not agree with how most people define it. After all, the eye is determined not only by the presence of several parts. These parts, working together, do some work, and each of them has its own task. But Makshi and Brandon believe that the complexity they study may lead to other types of complexity. “The complexity that we see in the Drosophila population serves as the basis for very interesting phenomena that selection can control,” in order to build complex structures that work to ensure survival, says Makshi.

Molecular complexity

As a paleobiologist, Makshi is accustomed to reflect on the complexity that occurs in fossils - for example, the bones that make up the skeleton. In recent years, several molecular biologists have independently begun to talk about the reasons for the occurrence of complexity in the same vein as he.

In the 1990s, a group of Canadian biologists began to study the absence of a visible effect of certain mutations on the body. In the jargon of evolutionary biology they are called neutral. Scientists, among whom was Michael Gray [Michael Gray] from Dalhousie University in Halifax, suggested that these mutations could lead to the emergence of complex structures, bypassing intermediate options selected for their help in adapting the organism to the environment. They called this process "constructive neutral evolution."

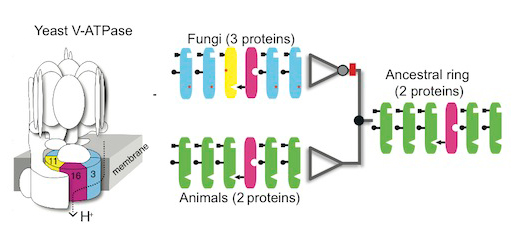

Gray was inspired by the latest research, offering very interesting confirmation of the existence of constructive neutral evolution. One of the leaders of this study is Joe Thornton of the University of Oregon. He and his colleagues found an example of such an evolution in fungal cells. In mushrooms such as champignon dvuhorovy , cells to maintain life, you must move atoms from place to place. To do this, they, in particular, use molecular pumps called "vacuolar adenosine triphosphate complex" [V-ATPase]. The rotating protein ring sends atoms from one side of the membrane in the fungus to the other. This ring is obviously a complex structure. It contains six protein molecules. Four of them consist of the Vma3 protein, the fifth is Vma11, the sixth is Vma16. And all three types of proteins are necessary for ring rotation.

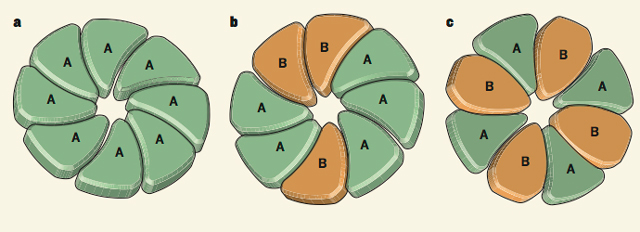

An example of how a complex structure can evolve without selection. A) Gene A encodes a protein with a structure that allows its eight copies to form a ring. B) Gene is randomly copied. Initially, two types of proteins can be made into a ring in any order. C) Mutations remove some sites that bind proteins. Now proteins can be combined only in a certain way. The ring has become more difficult, but not due to natural selection.

To find out how this complex structure came about, Thornton and colleagues compared proteins with their related versions in other organisms, for example, animals (fungi and animals had a common ancestor that lived a billion years ago).

In animals, the V-ATPase complexes also consist of rotating rings made up of six proteins. But they have a cardinal difference: instead of the three types of proteins, there are only two. Each animal ring consists of five copies of Vma3 and one Vma16. They do not have Vma11. By definition, the difficulty is from Makshi and Brandon, mushrooms are more complex than animals - at least in the V-ATPase area.

Scientists have studied more closely the genes encoding the proteins of the rings. Vma11, unique to mushrooms, turned out to be a close relative of Vma3 in animals and mushrooms. That is, the Vma3 and Vma11 genes must have common ancestors. Thornton and his colleagues concluded that somewhere at the beginning of the evolution of the fungus, the gene-ancestor of the ring proteins was accidentally copied. These two copies evolved into Vma3 and Vma11.

Studying the differences between the Vma3 and Vma11 genes, Thornton and colleagues recreated their ancestor gene. They then used this DNA sequence to create the corresponding protein — essentially, resurrecting a protein 800 million years old. They called it Anc.3-11 - short for “ancestor Vma3 and Vma11”. They wondered how the protein ring would work with this protein. They inserted the Anc.3-11 gene into the yeast DNA, and also turned off the descendants of this gene, Vma3 and Vma11. Under normal conditions, disabling these genes would end up badly for the yeast, since they could not create their own rings. But it turned out that the yeast can survive by using Anc.3-11 instead. They combined Anc.3-11 with Vma16 to create fully functional rings.

Such experiments allow scientists to formulate a hypothesis of how complicated the ring of mushrooms. The fungi began with a ring consisting of only two proteins, such as can be found in animals. Squirrels were universal, could connect with themselves or with their partners, on the right and on the left. Later, the gene for Anc.3-11 was copied and turned into Vma3 and Vma11. new squirrels continued the work of old, and gathered in rings. But for millions of generations of mushrooms, they began to mutate. Some of the mutations deprived of their universality. Vma11 lost the ability to connect with Vma3 clockwise. Vma3 lost the ability to connect in Vma16 clockwise. This did not kill the yeast, since proteins could still form a ring. That is, these were neutral mutations. But now the ring had to be more complicated, since it could only be formed from three proteins that are in a certain sequence.

Thornton and his colleagues uncovered exactly the type of evolution that the zero-force evolution law predicted. Over time, life produced more and more parts - ring proteins. Then these additional parts began to differ from each other. As a result, fungi have a more complex structure than their ancestors. But this did not happen as Darwin imagined, with natural selection favoring several intermediate options. Instead, the mushroom ring has degenerated and become more complicated.

Error correction

Gray discovered another example of constructive neutral evolution in the way that many species edit their genes. When cells need to create a protein, they rewrite the DNA of its gene in RNA, a single-stranded DNA copy, and then use special enzymes to replace some parts of the PKH (nucleotides) with others. RNA editing is necessary for many species, including us - non-edited RNAs produce non-working proteins. But it is still strange - why do we simply do not have genes with the initially correct sequence, which would exclude the need to edit RNA?

The scenario of RNA evolution proposed by Gray is the following: the enzyme mutates in such a way that it becomes able to join RNA and change certain nucleotides. This enzyme does not damage and does not help the cell - at least first. In the absence of harm, it is preserved. A harmful mutation occurs later in the gene. Fortunately, the cell already has an enzyme that combines with RNA that can compensate for this mutation by editing RNA. It protects the cell from the harm of mutation, and allows it to pass on to the next generation and spread throughout the population. The evolution of an RNA-editing enzyme and the mutation it fixed was not the result of natural selection, says Gray. On the contrary, this additional level of complexity arose by itself - “neutral”. After its spread, it was already impossible to get rid of it.

David Speijer, a biochemist from the University of Amsterdam, believes that Gray and his colleagues did biology a favor by expressing the idea of constructive neutral evolution, especially questioning the view that all complexity must be adaptive. But Speyer is worried that in some cases they are pushing their idea too far. On the one hand, he believes that pumps in mushrooms are a good example of constructive neutral evolution. “Any reasonable person will fully agree with this,” he says. In other cases, such as RNA editing, scientists, in his opinion, should not discard the possibility of the involvement of natural selection, even if this complexity seems useless.

Gray, Makshi and Brandon recognize the important role of natural selection in increasing the complexity of the environment around us, from the biochemistry of feathers to the factories of photosynthesis contained in the leaves of trees. But they hope that their research will convince other biologists to go beyond natural selection and see the possibility that random mutations are able to feed the evolution of complexity on their own. “We do not reject the role of adaptation in this process,” says Gray. “We just don’t think she can explain everything.”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/401953/

All Articles