Multiple universes may be the same universe.

If the concept of the multiverse seems strange, it is because we need to change our ideas about time and space.

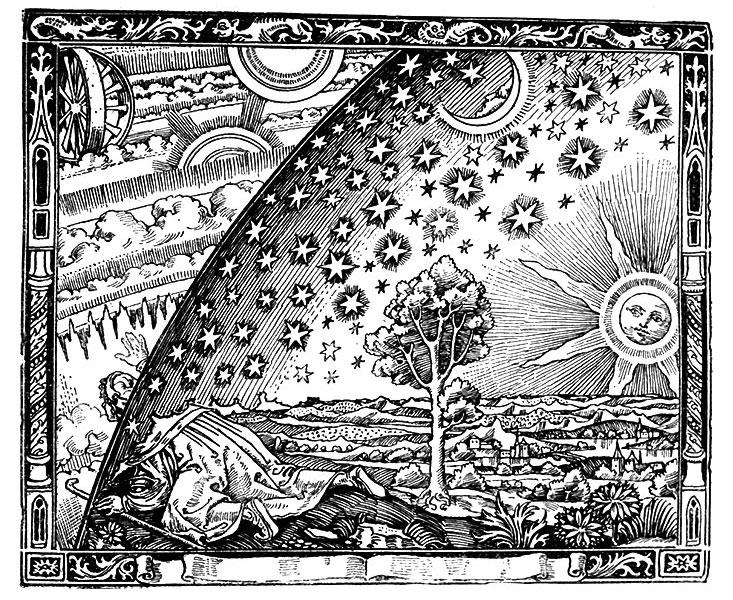

The title of the image, “Flammarion Engraving,” may not be known to you, but you most likely have seen it many times. It depicts a pilgrim in a raincoat and with a staff. Behind him is a landscape of cities and trees. It is surrounded by a crystal shell, speckled with countless stars. He reached the edge of the world, penetrated to his other side and gazed in amazement at the new world of light, rainbows and fire.

The image was first published in the 1888 book of the 19th century French astronomer Camille Flammarion "Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology". Initially, it was black and white, although now you can find colored versions. He notes that the heavens really look like a dome, on which celestial bodies are fixed, but the impressions are deceptive. “Our ancestors,” writes Flammarion, “imagined that this blue vault is the way their eyes see it. But, as Voltaire wrote, it is as meaningful as the silkworm, spinning its network to the limits of the universe. "

')

The engraving is considered as a symbol of humanity’s search for knowledge, but I prefer to see in it a more literal meaning described by Flammarion. Many times in the history of science, we have found a break in the knowledge of the border and pierced through it. The universe does not end behind the orbit of Saturn, or beyond the farthest stars of the Milky Way, or beyond the farthest galaxies visible to us. Today, cosmologists believe that there may be completely different universes.

But compared to the discoveries of quantum physics, this is almost trivial. This is not just a new hole in the dome, but a new type of hole. Physicists and philosophers have long argued about the meaning of quantum theory, but somehow, they agree that it opens up a vast world beyond our senses. Perhaps the simplest result of this principle is the most direct reading of the equations of quantum theory — a multi-world interpretation made by Hugh Everett in the 1950s. From his point of view, everything that can happen occurs somewhere in an infinite set of universes, and the probabilities of quantum theory represent the relative number of universes in which one or another scenario takes place. As David Wallace, the philosopher of physics from the University of Southern California, wrote in his 2012 book, The Emergent Multiverse, with literal perception of quantum mechanics, “the world turns out to be much larger than we expected: in fact, our classic„ world “Turns out to be a small part of a much larger reality.”

This set of universes, at first glance, seems to be very different from what is being interpreted by cosmologists. The cosmological multiverse grew out of models trying to explain the uniformity of the Universe on scales exceeding galactic ones. The assumed parallel universes are remote separate regions of space-time resulting from their own large explosions, developing from their bubbles of quantum foam (or from which they also grow universes). They exist about the same way as galaxies - you can imagine how we sit on a spaceship and go to them.

But unlike this approach, Everett's many-worlds interpretation does not lead us so far. The concept came about through attempts to understand the laboratory measurement process. Particles leaving traces in Wilson’s chamber, atoms reflected by magnets, hot objects emitting light: all these were practical experiments that led to the creation of quantum theory and to the search for a logically consistent interpretation. The quantum branching that occurs in the process of measurement creates new worlds, superimposed on the same space in which we exist.

However, these two types of multiverse have much in common. Transfer to any of the types we can only mentally. Fly to another universe of the bubble in the spacecraft will not work, because the space will expand faster. Therefore, these bubbles are separated from each other. We are also separated by nature from other universes in the quantum multiverse. These worlds, although they are real, will remain forever out of our sight.

Moreover, although the quantum multiverse was not developed for cosmology, it is surprisingly well suited to it. In the generally accepted quantum mechanics - in the Copenhagen interpretation, adopted by Niels Bohr and his comrades - it is necessary to distinguish between an observer and what he observes. For ordinary physics in laboratories, everything is in order. The observer is you, and you are watching the experiment. But what if the object of observation is the whole universe? You cannot get beyond it to measure it. Multi-world interpretation does not make such artificial separations. In the new work, Caltech physicist Sean Carroll, along with graduate students Jason Pollack and Kimberly Boddy, directly apply a multi-world interpretation to creating universes in the cosmological multiverse. “Everything in the usual quantum mechanics was neither fish nor meat becomes, in principle, counted from the Everett point of view,” says Carroll.

And finally, two types of multiverse give the same prediction of observations. The difference is that they put possible results in different places. Carroll thinks that the "cosmological multiverse in which different states are located in separated regions of space-time and the localized multiverse where different states are right here, just in different branches of the wave function" are similar.

MIT cosmologist Max Tegmark [Max Tegmark] outlined this idea during a report in 2002, which evolved into his 2014 book, Our Mathematical Universe [Our Mathematical Universe]. He describes several levels of the multiverse. Level I - the most remote regions of our own universe. Level III - his designation of the quantum set of worlds (he also has levels II and IV, but this is not about them now). To see the similarities between levels I and III, you need to think about the nature of probability. If something can have two results, you see one of them, but you can be sure that the other has also happened - either in another part of the giant universe, or right here, in a parallel world. If the cosmos is large enough and filled with matter, the events taking place here on Earth will also occur somewhere else, like any possible variants of these events.

For example, you are conducting an experiment in which you send an atom to a pair of magnets. You will see how it rushes to the lower or upper magnet, with a probability of 50%. In the multi-world interpretation, there are two worlds intersecting in your laboratory. In one the atom goes up, in the other - down. In the cosmological multiverse there are other universes (or parts of our Universe) with an identical twin of the Earth, on which the humanoid performs exactly the same experiment, but with a different result. Mathematically, these situations are identical.

Not everyone likes the multiverse, especially the similar multiverse options. But given the preliminary nature of these hypotheses, let's see where they lead us. They offer a radical idea: that the two multiverse ones do not have to be separate - that the multiworld interpretation does not differ from the cosmological concept of the multiverse. If they seem different, it is because we misunderstand reality.

A Stanford physicist, Leonard Saskind, suggested that they should be considered equal in the 2005 book The Cosmic Landscape. “Everett's multi-world interpretation, at first glance, seems to be very different from the ever-expanding megavers,” he writes (using his own term for the multiverse). "However, I think that two interpretations can speak of the same thing." In 2011, he and Rafael Bousso, a physicist at Berkeley, wrote together a paper in which they argue that the two ideas are identical. They say that the only way to give meaning to the probabilities associated with quantum mechanics and the phenomenon of decoherence — by which our classical categories of positions and velocities emerge — will be the application of a multi-world interpretation to cosmology. As a result, the cosmological multiverse should naturally come out. In the same year, Yasunori Nomura [Yasunori Nomura] from the University of California at Berkeley substantiated a similar idea in his work, where he “ensures the unification of the processes of quantum measurements and the multiverse”. Tegmark uses roughly the same argument in the work of 2012 , written jointly with Anthony Aguirre from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

From this point of view, many quantum worlds are located not directly next to us, but far from us. The wave function, as Tegmark writes, describes not "some incomprehensible imaginary set of possibilities of what an object can do, but a real spatial collection of identical copies of an object that exist in infinite space."

The bottom line is that you need to think about your point of view. Imagine that you are looking at a multiverse from the position of God, from which you can see all the opportunities that are being realized. There are no probabilities. Everything happens with certainty in one of the places. From a limited point of view of our world, tied to the planet Earth, various events unfold with different probabilities. “We are changing the global picture, in which absolutely everything happens somewhere, but no one can see everything at once - to a local one, in which you have one, basically knowable, section,” says Bousso.

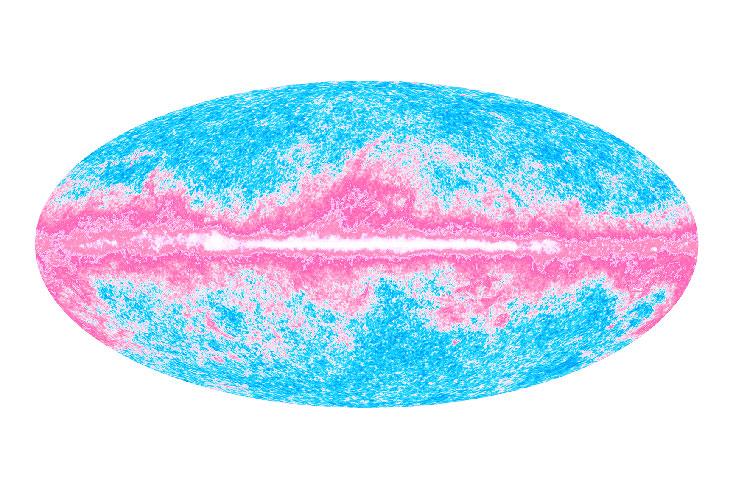

Many cosmologists find evidence of the existence of much larger space in the relic radiation image, than we can directly observe

To go from global to local, we need to cut the universe in order to separate the measurable from the unmeasured. Measured is our “causal plot,” as Busso calls it. This is the sum of everything that can affect us - not only the observable universe, but also the region of space that will be available to our distant descendants. Cutting out our section from the rest of the space-time, one can imagine what observations we can make, and as a result we get the quantum mechanics in the old style.

From this point of view, the cause of the uncertainty of quantum events is that we do not know where we are in the multiverse. In infinite space, there are an infinite number of creatures that look and behave exactly like you are in everything. The main mystery covers the classic caricature of the New Yorker. On a piece of ice is a crowd of identical penguins. One of them asks: "And which of us am I?"

The poor penguin still has the opportunity to establish his location through the triangulation of the nearest floating ice, but there are no such reference points in the multiverse, so we can never split our multiple copies. David Deutsch [David Deutsch] - a physicist from Oxford, and, like Carroll and Tegmark, a loyal supporter of a multi-world interpretation - writes in his book The Fabric of Reality: “Assuming the meaning of which of the identical copies is I mean to assume that there is a certain frame of reference outside the multiverse with respect to which one can answer this question: "I am third from the left." But what is this “left” and what is this “third”? There is no "point of view outside the multiverse". "

Tegmark says that, in essence, the concept of probability in quantum mechanics reflects "your inability to find yourself in the multiverse level I, that is, to know which of the infinite number of your copies in space possesses your subjective feeling." In other words, events look probabilistic, because you never know which of you is you. Instead of not being sure how the experiment will go, he goes all the way; you are simply not sure which of you is observing which of its results.

For Busso, the mathematical success of such an approach is enough, and he is not going to suffer from insomnia because of how someone will determine the deep meaning of the merged multiverse. “In essence, what matters is what predictions your theory makes and how they relate to observations,” he says. - Regions that are beyond our cosmological horizon cannot be observed, as well as the ramifications of the wave function, on which we did not find ourselves. These are just the tools we use for calculations. ”

But such an instrumental approach to physical theory does not satisfy many. We want to know what it all means - how reading the readings from the device can betray the existence of infinite bubbles in space-time. Massimo Pigliucci, a scientific philosopher at the City University of New York, says: "If you are talking about the real division of the universe, then explain to me how exactly this happens and where these other worlds are located."

Perhaps in order to understand the meaning of the connection between the multiverse variants, it is necessary to update our understanding of space and time. If the multiverse is at the same time somewhere far away and right here, perhaps this is a sign that our “out there” and “here” categories are failing us.

Almost two decades ago, Deutsch argued in her “Fabric of Reality” that the multiverse was inventing a new concept of time. Both in everyday life and in physics, we assume the existence of something like Newton's type of eternally current time. A multiverse is usually described as a structure that expands over time. In fact, time does not flow and does not pass, and we do not move on it in some mysterious way. Time is the way by which we determine movement. It cannot move. Therefore, the multiverse does not evolve. She just exists. Deutsch writes: "The multiverse did not" appear "and does not" disappear "; these terms suggest the passage of time. "

Instead of imagining how the multiverse unfolds in time, Deutsch believes that we should imagine how time unfolds in the multiverse. Other times are just special cases of other universes. Regardless, the physicist Julian Barbour [Julian Barbour] also fiddled with this idea in his 1999 book The End of Time. Some of these other universes, Deutsch writes, so strongly resemble our - our “now” - that we interpret them as parts of the history of our universe, and not as separate universes. For us, they are not somewhere in space, but on our time line. Just as we cannot perceive the entire universe at a time, we cannot perceive an infinite array of moments at a time. Instead, our perception reflects our perspective of embedded observers living in single moments. Moving from a global to a local point of view, we restore the familiar signs of time.

The multiverse can also correct our view of space. “Why does the world look classic?” Asks Carroll. “Why does space-time exist in four dimensions?” Carroll, who made a blog entry on the union of the multiverse, acknowledges that Everett does not answer these questions, “but gives you a platform on which to base them.”

He believes that space is not fundamental, but is the result of some phenomenon. But where does it come from? What actually exists? For Carroll, Everett’s image provides a simple answer to this question. “The world is a wave function,” says Carroll. - This is an element of the Hilbert space. That's all".

Hilbert space is a mathematical space associated with a quantum wave function. This is an abstract representation of all possible system states. It is a bit like Euclidean, but the number of measurements varies, and depends on the number of permissible system states. In qubit - the fundamental unit of data in quantum computers capable of taking the value 0, 1, or in their superposition, the Hilbert space is two-dimensional. A continuous quantity, such as position or velocity, corresponds to an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space.

Physicists usually start with a system that exists in real space, and derive the Hilbert space from it, but Carroll believes that this process can be reversed. Imagine all possible states of the universe and come to the point in which of the spaces the system should exist - if it exists at all in a certain space. A system can exist not in one, but in several spaces at the same time, and then we will call it a multiverse. Such a view "naturally lies on the idea of the emerging space-time," says Carroll.

Some people - especially philosophers - refuse such an approach. Hilbert space can be a valid mathematical tool, but this does not mean that we live in it. Wallace, who supports the multi-world interpretation, says that the Hilbert space is not literally an existing structure, but a way of describing real things - strings, particles, fields, or what else the universe consists of.“In a metaphorical sense, we live in a Hilbert space, but not literally,” he says.

Hugh Everett did not live to see a renewed interest in his version of quantum mechanics. He died of a heart attack in 1982, at 51. He was an unshakable atheist and was convinced that this was the end; his wife, following his instructions, threw the ashes along with the garbage. But his message is probably starting to take root. It can be summarized briefly: be serious about quantum mechanics. In this case, we discover that the world is a surprise! - becomes richer and more than we imagined. Just like Voltaire, the silkworm saw only its network, we see only a small piece of the multiverse, but thanks to Everett and his followers, we can still squeeze through a crack in the crystalline shell “where the earth meets the sky” and take a quick look on what extends beyond.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/401331/

All Articles