Entertaining music: Number 5 and a little about how the usability and the programmer “see” the music

Andrew Duncan, a software engineer and musician, begins his work “Combinatorial Theory of Music” by saying that there are no professions more distant than the musician and mathematician - however, paradoxically for musicians and mathematicians themselves, music and its creation can serve as excellent example of the work of a number of mathematical concepts.

In the materials of this series we recall some interesting examples and phenomena linking music, mathematics (in this case, combinatorics) and even history.

Pascal / PD Photography

Pascal / PD Photography

')

In fact, there are a lot of “magic” numbers in music: from the “seven notes” that we know from childhood, then the “magic number three” in a triad and 12 sounds of the chromatic scale. However, among all the numbers related to music in one way or another, one deserves special attention - this is the number 5 and the associated pentatonic scale.

This gamma is interesting primarily because it differs from the "traditional" western (diatonic) seven-seven version (the word "pentatonic" comes from the Greek "five" - according to the number of notes in the pentatonic scale), while it is not a truncated version of the conventional interval system ( just the pentatonic series - unlike the diatonic one - does not contain semitones). And despite the fact that now everyone is accustomed to "diatonic music", the pentatonic musical tradition, even though it sounds a bit unusual for modern hearing, is much older.

Saying "much", it is worth bearing in mind not thousands, but tens of thousands of years. It was on the pentatonic scale that the oldest musical instruments in the world were tuned (discovered to date). In 2008, archaeologists carried out excavations in the south of Germany and in one of the caves they found flutes made from vulture bones and mammoth tusks, which are approximately 35-40 thousand years old .

The fact that the age of the pentatonic scale is so ancient allows us to make assumptions about the role such music played in the life of primitive people. Ethan Hein , professor of music at the State University of Montclair, USA, inspired by the film Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams , in which these flutes were shown, makes the assumption that the pentatonic scale and “pentatonic music” were sacred for the ancients — if only because that making such a flute in the Stone Age was an incredibly complex and extremely time-consuming process.

By the way, on the flute tuned to the pentatonic scale, you can play “diatonic” music - which is what one of the paleontologists does, armed with a modern copy of an ancient instrument:

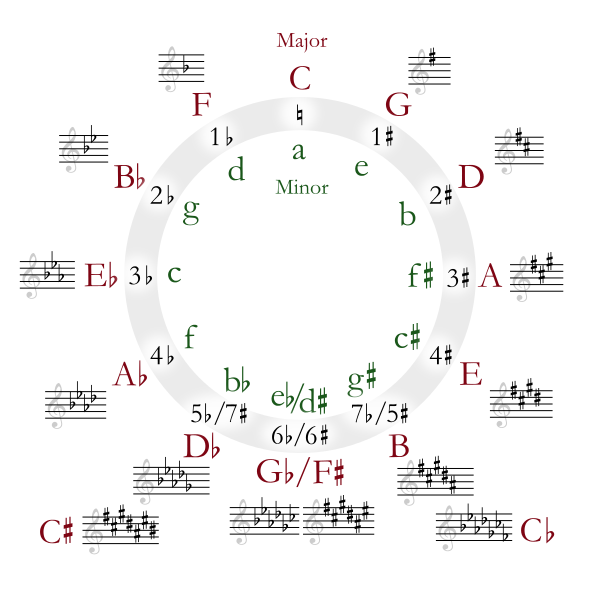

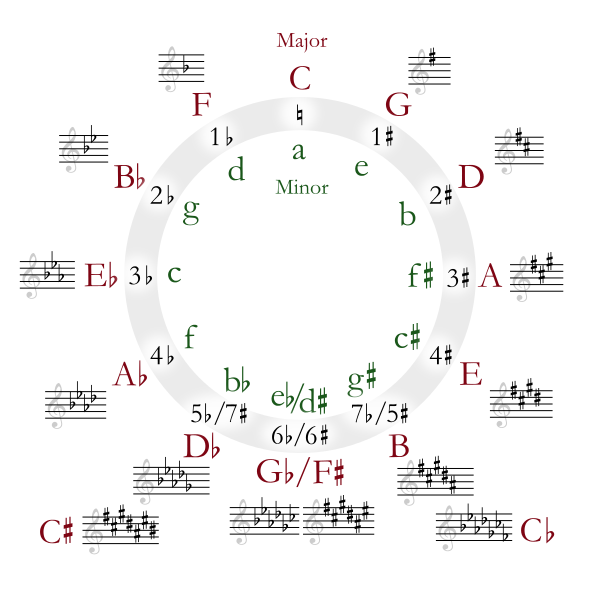

Another concept in music, closely related to the number 5 - the so-called quinte circle. The Quint Circle is a graphic scheme that allows musicians to systematize knowledge about keys, “signs at a key” and in some cases facilitates improvisation and writing music.

Quint circle of minor and major keys and their signs in the Wiki / CC key

Quint circle of minor and major keys and their signs in the Wiki / CC key

The quint circle was first described in the book “The Idea of the Musician Grammar” from 1679 by the Russian-Ukrainian composer Nikolai Diletsky (although, of course, the very idea of such a connection between the tonalities existed before). In detail about how (including from the “combinatorial” point of view) the fifth circle is built, we have already told here .

One has only to add that within the framework of one melody, the change of tonality to a “neighbor” in a quinte circle is not only logical from the standpoint of mathematics, but is also perceived by the ear as a harmonious musical transition. At the same time, as Ethan Hein remarks, the change of tonalities within the circle usually depends on the genre - in jazz, tonalities are replaced counterclockwise, in rock - clockwise.

By the way, the pentatonic scale and the quint circle are connected - in fact, the notes of the pentatonic scale go in a row on the fifth circle (more about this - and also about how the ancient pentatonic scale may sound in the modern jazz repertoire - you can read in the blog of the American saxophonist Anton Schwartz).

A question that torments many novice musicians - why is music recorded this way? There are several explanations, in addition, modern researchers do not leave attempts to come up with a new system of musical notation - more convenient for newly-made musicians or even scientists.

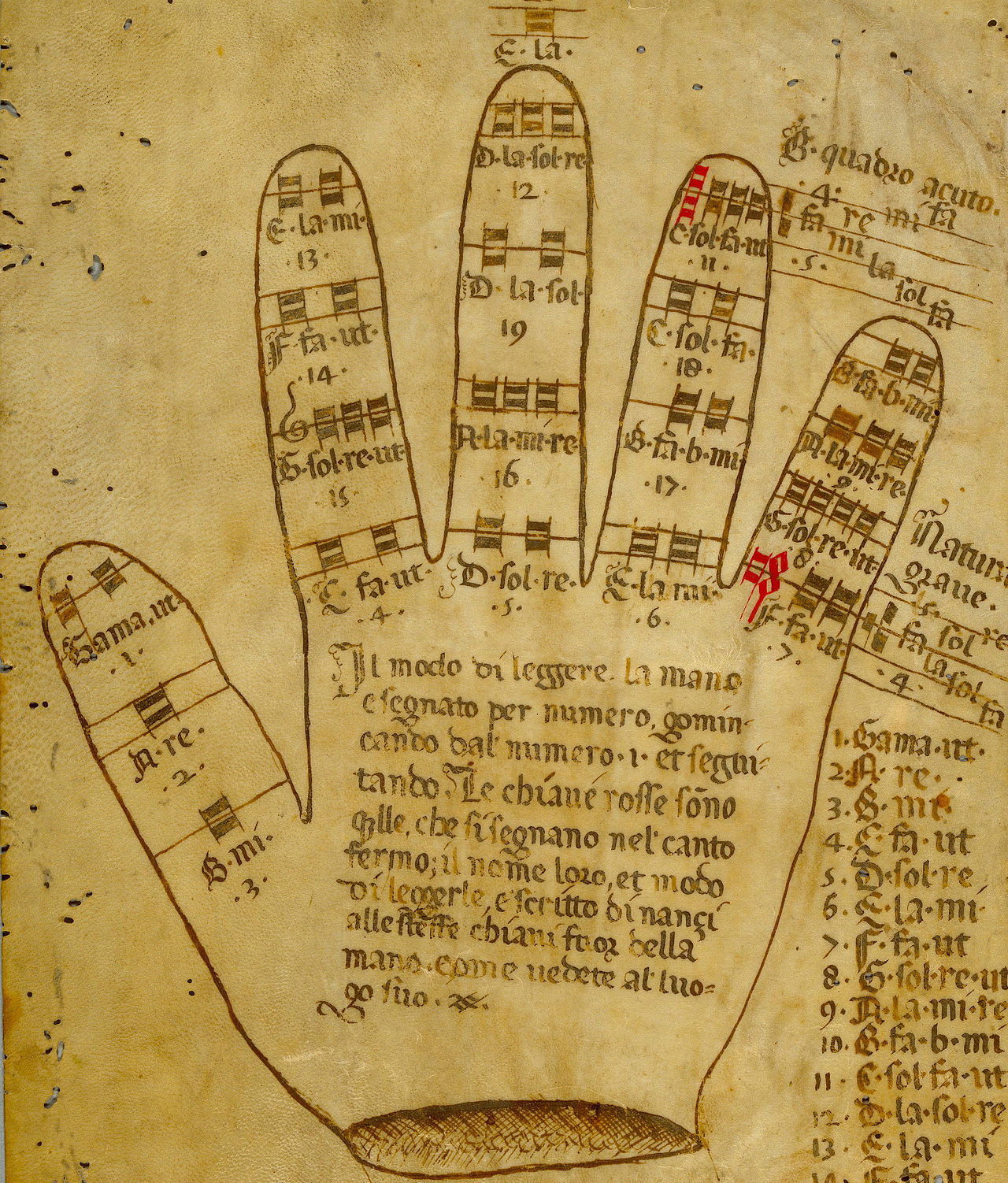

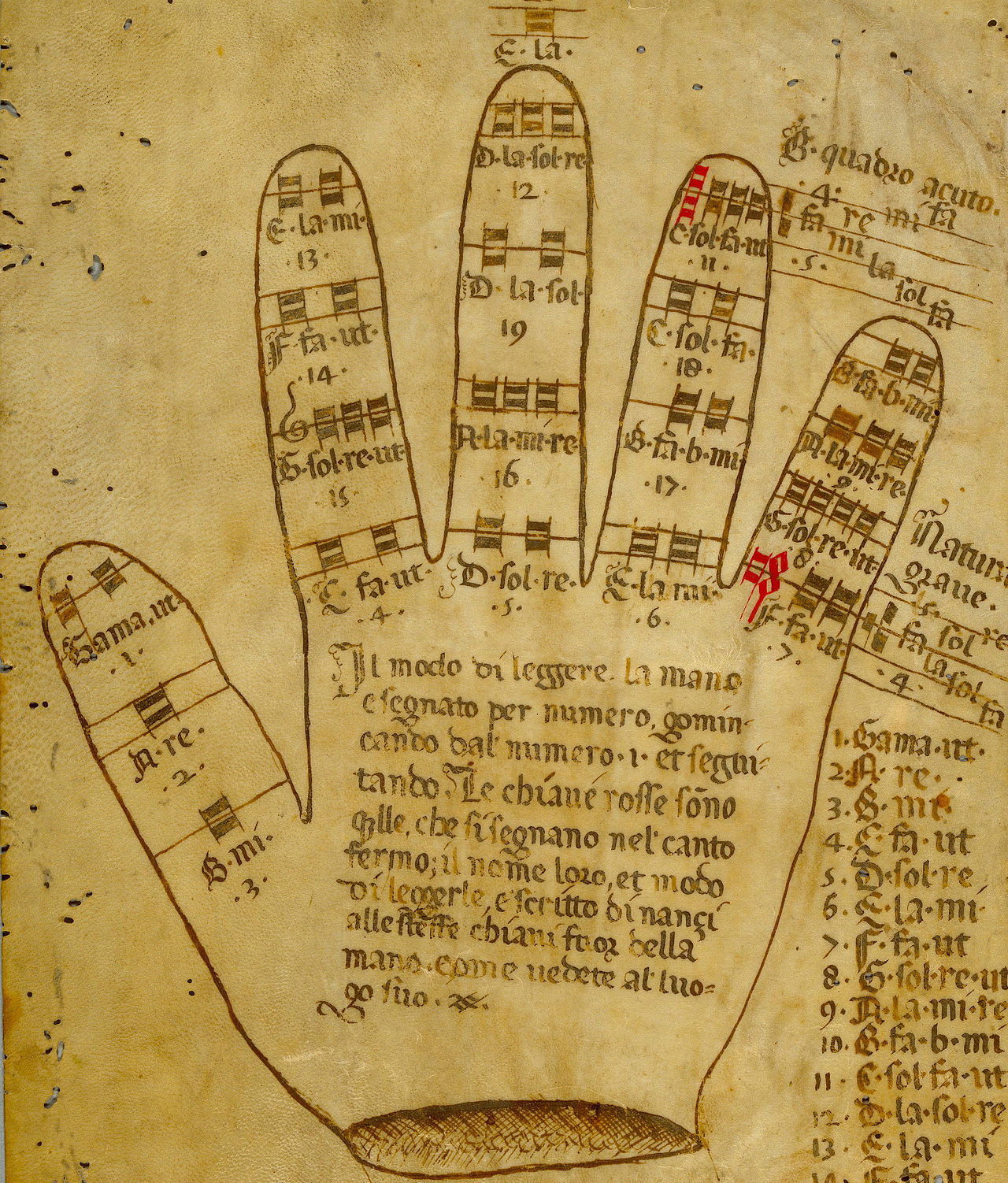

Guidonov hand. Miniature from the Mantuan manuscript of the end of the 15th century Wiki / PD

Guidonov hand. Miniature from the Mantuan manuscript of the end of the 15th century Wiki / PD

Historically, one of the earliest versions of musical notation (along with letter notations) was the so-called Gvidonov Hand, invented by the monk of the Benedictine Order Guido d'Arezzo (c. 991 - 1033). Such a recording system helped novices learn to memorize chorale melodies faster, calculate intervals and determine the pitch of sounds, and was the basis of Western musical theory for hundreds of years (we told more about how the Gvidon Hand “works” here ).

Strictly speaking, it is a system that allows understanding the relationship of notes and intervals within hexachords and memorizing one or another melodic sequence - it is of little use for recording classical and modern music, if only because it does not give any instructions regarding the rhythm of the melody, the duration of the sound ( and many other features that are commonly reflected in modern music).

Photo by Brandon Giesbrecht / PD

Modern musical notation (or the fact that most musicians are used to using now) is much more detailed and contains many specifying moments and nuances regarding rhythm and tempo, features of the game, pitch, level of expressiveness and other performance details. It should be noted that the “modern” musical notation did not become so immediately - as the European musical tradition developed, it also became more complicated.

The main problem of modern musical notation is its complexity. That is why, for example, many guitarists do not bother to study it, limited to tablature (by the way, not only guitar, but organ and harpsichord tablature were popular in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, and in general this kind of musical notation then competed with that that we consider “classical notes”).

By the way, at the beginning of the 19th century, an attempt was made to slightly simplify the classical system of musical notation: instead of the standard notation, it was proposed to write notes with ovals using various geometric figures . This method of notation, however, did not catch on - although a few studies have shown that it is really easier to read such notes from a sheet.

However, along with the “traditional” notation, modern musicians, composers and even scientists do not give up trying to derive a new system of schematic recording of notes (and even make attempts to create a “periodic music system” - by analogy with the periodic table - but more on that later). For example, Alex Couch, a UX specialist and great music lover, proposed a modern version of musical notation, convenient for beginners.

In his article on medium, he gives a recording option (and several pieces of music recorded in this way), which is suitable for novice pianists, and especially for those who want to quickly master the songs of modern pop singers. Such a notation (as the author himself confirms) does not provide information about the rhythm and speed of the game — in order to understand how the work actually needs to be played, the author advises to refer to the original and listen to the track in the recording.

However, this is not the only modern version of music visualization. So, for example, Andrew Duncan, already mentioned in the introduction to the article, set himself the goal of calculating how many variations there are in the 12-ton chromatic scale and how these variations, as well as chords and intervals, are related to each other.

To this end, he (as well as in the case of the fifth circle) decided to combine notes into a vicious circle of 12 elements, in which each element (or semitone) is colored black (if it is present in the selected key / interval / chord) or white (otherwise) [in the video below, the logic of coloring elements is the opposite - as the author himself says, this change in the original concept is made for simplicity of perception].

As a result, as it is easy to guess, the author received 2 ^ 12 = 4096 different variations. What is of interest here is what visual display this gigantic scheme received: in one image, the researcher did not just fit all the resulting tonalities, intervals and chords, but also painted them in the corresponding colors according to their equivalence classes (two or more were considered equivalent in this study combinations based on the same principles from different notes - for example, all quarts or all major triads).

In fact, this diagram shows the whole theory of music or, as the author himself says, “musical periodical system” (in the article devoted to this study of the author, there are even more interesting conclusions that such a scheme of visual representation allows to make).

PS In the following materials from this series we will continue to talk about music theory, the development of musical genres and how music is related to the exact sciences.

PPS Today we are holding Audio Monday - a big sale that will last only one day (while products are available).

In the materials of this series we recall some interesting examples and phenomena linking music, mathematics (in this case, combinatorics) and even history.

Pascal / PD Photography

Pascal / PD Photography')

"Magic" number 5

In fact, there are a lot of “magic” numbers in music: from the “seven notes” that we know from childhood, then the “magic number three” in a triad and 12 sounds of the chromatic scale. However, among all the numbers related to music in one way or another, one deserves special attention - this is the number 5 and the associated pentatonic scale.

This gamma is interesting primarily because it differs from the "traditional" western (diatonic) seven-seven version (the word "pentatonic" comes from the Greek "five" - according to the number of notes in the pentatonic scale), while it is not a truncated version of the conventional interval system ( just the pentatonic series - unlike the diatonic one - does not contain semitones). And despite the fact that now everyone is accustomed to "diatonic music", the pentatonic musical tradition, even though it sounds a bit unusual for modern hearing, is much older.

Saying "much", it is worth bearing in mind not thousands, but tens of thousands of years. It was on the pentatonic scale that the oldest musical instruments in the world were tuned (discovered to date). In 2008, archaeologists carried out excavations in the south of Germany and in one of the caves they found flutes made from vulture bones and mammoth tusks, which are approximately 35-40 thousand years old .

The fact that the age of the pentatonic scale is so ancient allows us to make assumptions about the role such music played in the life of primitive people. Ethan Hein , professor of music at the State University of Montclair, USA, inspired by the film Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams , in which these flutes were shown, makes the assumption that the pentatonic scale and “pentatonic music” were sacred for the ancients — if only because that making such a flute in the Stone Age was an incredibly complex and extremely time-consuming process.

By the way, on the flute tuned to the pentatonic scale, you can play “diatonic” music - which is what one of the paleontologists does, armed with a modern copy of an ancient instrument:

A couple more words about number 5

Another concept in music, closely related to the number 5 - the so-called quinte circle. The Quint Circle is a graphic scheme that allows musicians to systematize knowledge about keys, “signs at a key” and in some cases facilitates improvisation and writing music.

The quint circle was first described in the book “The Idea of the Musician Grammar” from 1679 by the Russian-Ukrainian composer Nikolai Diletsky (although, of course, the very idea of such a connection between the tonalities existed before). In detail about how (including from the “combinatorial” point of view) the fifth circle is built, we have already told here .

One has only to add that within the framework of one melody, the change of tonality to a “neighbor” in a quinte circle is not only logical from the standpoint of mathematics, but is also perceived by the ear as a harmonious musical transition. At the same time, as Ethan Hein remarks, the change of tonalities within the circle usually depends on the genre - in jazz, tonalities are replaced counterclockwise, in rock - clockwise.

By the way, the pentatonic scale and the quint circle are connected - in fact, the notes of the pentatonic scale go in a row on the fifth circle (more about this - and also about how the ancient pentatonic scale may sound in the modern jazz repertoire - you can read in the blog of the American saxophonist Anton Schwartz).

How can you visualize notes

A question that torments many novice musicians - why is music recorded this way? There are several explanations, in addition, modern researchers do not leave attempts to come up with a new system of musical notation - more convenient for newly-made musicians or even scientists.

Historical excursus: reading hands and drawing geometric shapes

Historically, one of the earliest versions of musical notation (along with letter notations) was the so-called Gvidonov Hand, invented by the monk of the Benedictine Order Guido d'Arezzo (c. 991 - 1033). Such a recording system helped novices learn to memorize chorale melodies faster, calculate intervals and determine the pitch of sounds, and was the basis of Western musical theory for hundreds of years (we told more about how the Gvidon Hand “works” here ).

Strictly speaking, it is a system that allows understanding the relationship of notes and intervals within hexachords and memorizing one or another melodic sequence - it is of little use for recording classical and modern music, if only because it does not give any instructions regarding the rhythm of the melody, the duration of the sound ( and many other features that are commonly reflected in modern music).

Photo by Brandon Giesbrecht / PD

Modern musical notation (or the fact that most musicians are used to using now) is much more detailed and contains many specifying moments and nuances regarding rhythm and tempo, features of the game, pitch, level of expressiveness and other performance details. It should be noted that the “modern” musical notation did not become so immediately - as the European musical tradition developed, it also became more complicated.

The main problem of modern musical notation is its complexity. That is why, for example, many guitarists do not bother to study it, limited to tablature (by the way, not only guitar, but organ and harpsichord tablature were popular in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, and in general this kind of musical notation then competed with that that we consider “classical notes”).

By the way, at the beginning of the 19th century, an attempt was made to slightly simplify the classical system of musical notation: instead of the standard notation, it was proposed to write notes with ovals using various geometric figures . This method of notation, however, did not catch on - although a few studies have shown that it is really easier to read such notes from a sheet.

Modern options: how the usability and the programmer "see" the music

However, along with the “traditional” notation, modern musicians, composers and even scientists do not give up trying to derive a new system of schematic recording of notes (and even make attempts to create a “periodic music system” - by analogy with the periodic table - but more on that later). For example, Alex Couch, a UX specialist and great music lover, proposed a modern version of musical notation, convenient for beginners.

In his article on medium, he gives a recording option (and several pieces of music recorded in this way), which is suitable for novice pianists, and especially for those who want to quickly master the songs of modern pop singers. Such a notation (as the author himself confirms) does not provide information about the rhythm and speed of the game — in order to understand how the work actually needs to be played, the author advises to refer to the original and listen to the track in the recording.

However, this is not the only modern version of music visualization. So, for example, Andrew Duncan, already mentioned in the introduction to the article, set himself the goal of calculating how many variations there are in the 12-ton chromatic scale and how these variations, as well as chords and intervals, are related to each other.

To this end, he (as well as in the case of the fifth circle) decided to combine notes into a vicious circle of 12 elements, in which each element (or semitone) is colored black (if it is present in the selected key / interval / chord) or white (otherwise) [in the video below, the logic of coloring elements is the opposite - as the author himself says, this change in the original concept is made for simplicity of perception].

As a result, as it is easy to guess, the author received 2 ^ 12 = 4096 different variations. What is of interest here is what visual display this gigantic scheme received: in one image, the researcher did not just fit all the resulting tonalities, intervals and chords, but also painted them in the corresponding colors according to their equivalence classes (two or more were considered equivalent in this study combinations based on the same principles from different notes - for example, all quarts or all major triads).

In fact, this diagram shows the whole theory of music or, as the author himself says, “musical periodical system” (in the article devoted to this study of the author, there are even more interesting conclusions that such a scheme of visual representation allows to make).

PS In the following materials from this series we will continue to talk about music theory, the development of musical genres and how music is related to the exact sciences.

PPS Today we are holding Audio Monday - a big sale that will last only one day (while products are available).

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/401179/

All Articles