January 1, 1925: the day we opened the universe

The Andromeda nebula, photographed at the Yerkes Observatory around 1900. For us, this is obviously a galaxy. Then it was described as a "mass of luminous gas" of unknown origin.

And what is special about this date? A new year is just a random scrolling of the calendar, but it can also serve as a moment of elevation, renewal and revision of views. It happened with one of the most unusual dates in the history of science, January 1, 1925. It can be said that nothing remarkable happened then, just a regular report at a scientific conference. Or it can be celebrated as the birthday of modern cosmology, the moment when humanity discovered the Universe as it is.

Before that, astronomers had a short-sighted and limited view of reality. As often happens even with the most brilliant minds, they saw, but did not understand what they were looking at. But the key fact was right before their eyes. There were interesting spiral nebulae scattered across the sky, whirlpools of light resembling tops. The most famous of them, the Andromeda nebula, was so bright that it could easily be seen at night. But the significance of these omnipresent objects remained a mystery.

Some believed that spiral nebulae were huge and distant star systems, “island universes,” comparable to our Milky Way galaxy. Many others were convinced that these were just small, closely spaced clouds of gas. From their point of view, other galaxies, if they exist, were not visible, and were far in the depths of space. Or maybe there were no other galaxies, but there was only one Milky Way - one system defining the Universe. The disputes between the two sides were so hot that they led to the famous Great Dispute of 1920, which ended in an unsatisfactory draw.

')

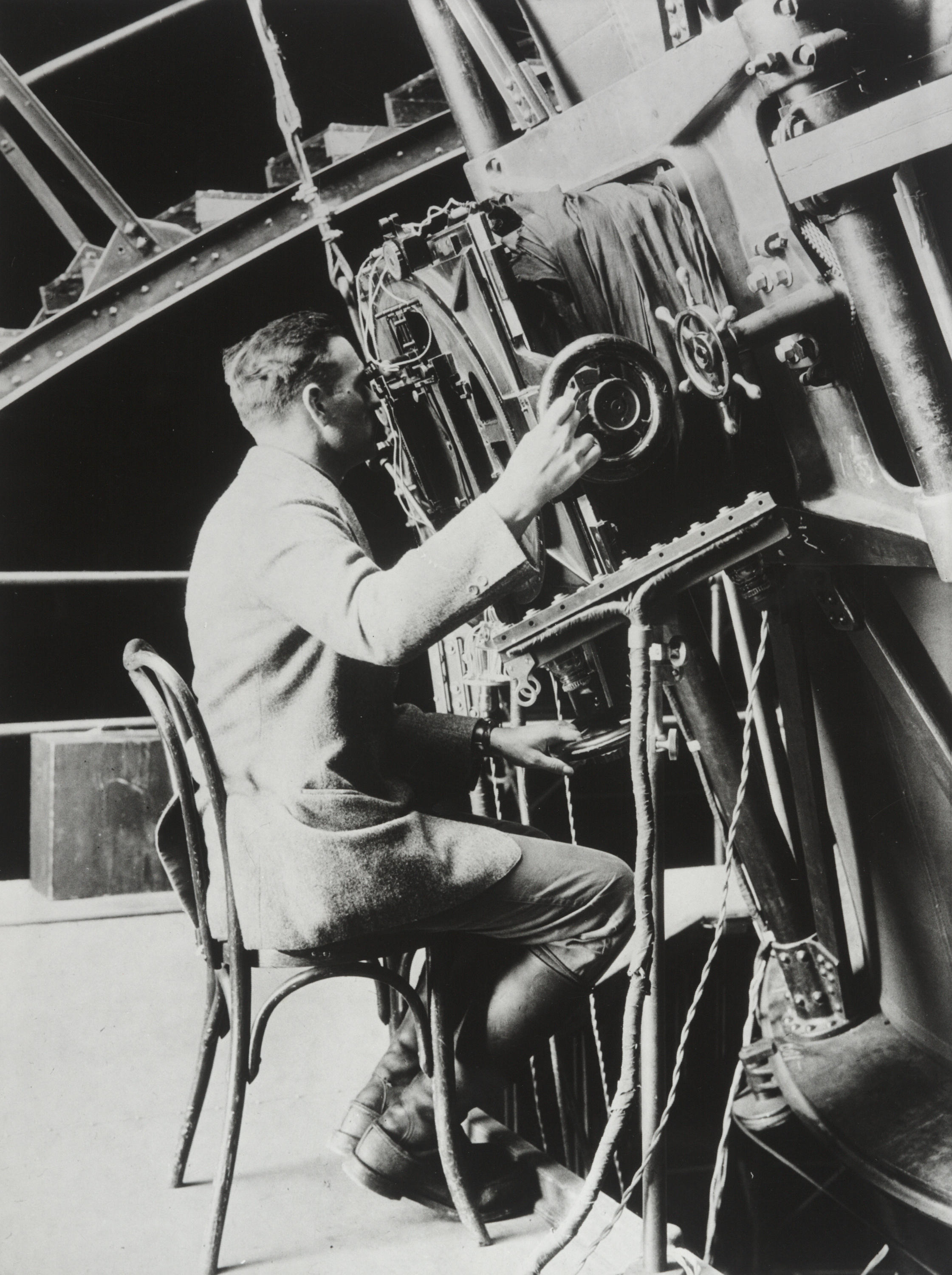

The correct idea of our place in the universe appeared only a few years later, in the work of one of the most famous astronomers: Edwin Powell Hubble. Since 1919, Hubble has become one of the most patient and meticulous observers at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California. But the observatory itself became the main avant-garde of astronomical research, the home of the recently created Hooker 100-inch telescope - then it was the largest telescope in the world. It was the perfect combination of the right observer in the right place at the right time.

Hubble was greatly helped by a previous study by Vesto Melvin Sliffer from Lowell Observatory, one of the unsung heroes of modern cosmology. Slipher discovered that many of the spiral nebulae are moving at tremendous speeds, faster than any of the known stars, and that they are moving mostly from us. For Slipher, this discovery was convincing evidence of the independence of these systems, driven by unknown mechanisms operating outside the Milky Way. But Slipfer lacked the necessary resources to prove his interpretation. He needed a giant telescope, such as Hubble managed on Mount Wilson. That's where our story switches to the top gear.

Edwin Hubble over the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson, circa 1922

Hubble was always careful about theories and interpretations. He concentrated his scientific attention on spiral nebulae without stressing the need to prove the theory of "island universes." He preferred to wait until he was able to present an unequivocal confirmation or refutation of this theory, depending on what the evidence indicated.

In 1922, another important piece of the puzzle appeared. That year, Swedish astronomer Knut Emil Lundmark saw what he considered to be separate stars in the arms of the spiral nebula M33. Shortly thereafter, John Duncan from the Mount Wilson Observatory noticed points of light fading and rising in the same nebula. Could these be variable stars, similar to those that exist in the Milky Way, but much dimmer because of the huge distance to them?

Feeling that the answer was close, Hubble redoubled his efforts. He spent the night in his favorite wooden chair, driving a steel mount of the Hooker telescope to eliminate the effects of the Earth's rotation. The attempt was crowned with success in the form of detailed images of the Andromeda nebula with a long exposure. The spotted light of the nebula began to turn into a multitude of bright dots that did not look like gas, but like a gigantic swarm of stars.

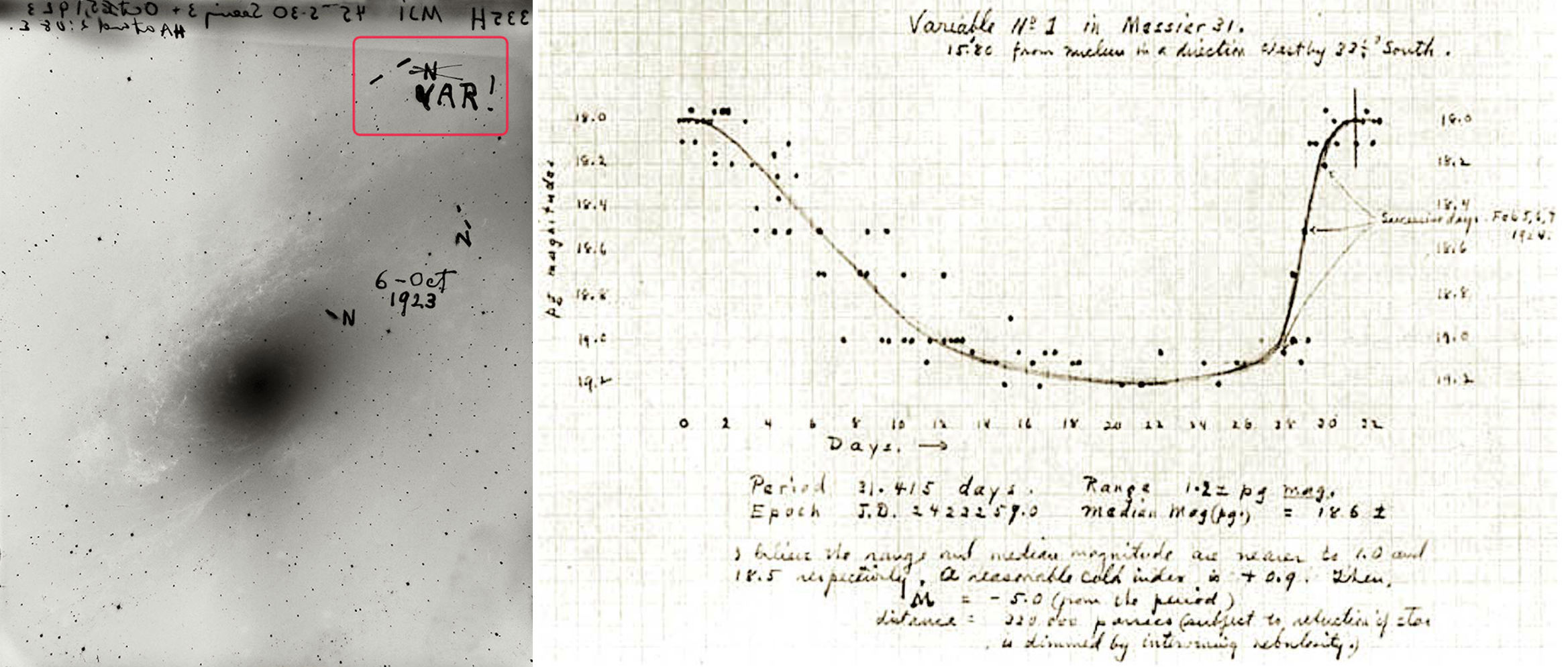

The final proof appeared in October 1923, when Hubble noticed the characteristic twinkling of a separate variable star from the Cepheid class in one of the Andromeda arms. The apparent brightness of such a star changes predictably and periodically, and its own brightness depends on the oscillation period. By just measuring the 31-day star blink cycle, Hubble could calculate the distance to it. According to his calculations, it turned out 930,000 light years - less than half of the current estimate, but for its time, it’s still a shocking figure. This distance positioned Andromeda, one of the brightest and, possibly, the nearest spiral nebulae, far beyond the Milky Way.

In principle, it was then that the Great Dispute was resolved. Spiral nebulae were other galaxies, and our Milky Way was just one of the outposts of a stunningly vast universe. But the story does not end there.

With his usual care, Hubble began to look for more evidence. The following February, he discovered, perhaps another Cepheid in Andromeda, several Cepheids in M33, and possibly another three nebulae. And when there was no doubt, he wrote about this news to his longtime rival, Harlow Shapley - a leading supporter of the idea of small and nearby spiral nebulae - with the aim of teasing him. “You will be interested to know that I found Cepheid in the Andromeda nebula,” the letter began.

Shapeley did not need to read further to understand the importance of Hubble’s words. “This letter has destroyed my universe,” said Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard, who turned out to be in the lab when Hubble arrived at the time, angrily. Payne-Gaposhkina was another key figure for modern astrophysics. By a surprising coincidence, her pioneering work on the stellar spectrum was completed on January 1, 1925!

Despite the obvious joyful excitement about discoveries in Andromeda, Hubble still hesitated with the publication of the results. With all the ostentatious confidence, he was terribly worried about the loud and premature announcement of the opening. Each time, going from a meeting to a formal dinner at 5 pm at the Monastery, living quarters of Mount Wilson, Hubble met with his fellow astronomers. Not all of them accepted the existence of other galaxies. Being a vain and carefully monitoring his reputation as a scientist, Hubble was afraid to look like a fool.

Adrian van Maanen, a cheerful and handsome Dutch astronomer on Mount Wilson, vigorously proved the opposite point of view. He was convinced that he observed the rotation of some of the spiral nebulae, which was possible only if they were small enough and were located close enough. Hubble was worried about the presence of a doubting scientist in his own ranks, and held on until he gained absolute confidence in the results. Van Maanen did not understand where he was wrong, and refused to admit the error. Hubble eventually revised the photographic plates of a colleague, and announced that "the rotations found earlier were the results of hidden systematic errors, and did not indicate nebula motion, real or apparent." From an academic point of view, this was a very harsh reproach.

The only variable star seen by Hubble in the Andromeda nebula has changed all of our ideas about the size of space. On the left - the image that helped the opening. On the right is the star's brightness curve.

Information about the discovery of Hubble inevitably leaked to the press. As a result, the first public announcement of an astronomical breakthrough was a small note that took place in The New York Times on November 23, 1924. The most important discovery related to space over the past three centuries, came out in the form of one piece of news from a whole heap!

And yet, Hubble was kept from formal publication. Renowned astronomer Henry Norris Russell persuaded him to present his discoveries at a meeting in the capital of the American Association for Scientific Achievements, which offered a prize of $ 1,000 for the best work. When Hubble never offered his job, Russell chuckled: “Well, he is a donkey. He is in the hands of a light thousand dollars, and he refuses to take it. ” And then Russell opened the mail, and found that the work from Hubble had just arrived.

And only now we come to the stunning public announcement. On January 1, 1925, Hubble was isolated on Mount Wilson, and Russell read his revolutionary work on the existence of other galaxies in front of a crowd full of enthusiasm. Hubble got part of the prize for the best work. She completed a big controversy, and not only. She dramatically increased the size of the known universe 100,000 times. She set the stage for the discovery of an expanding universe, and, as a result, the original Big Bang (which was already hinted at by the speeds recorded by Slipher). If you can assign a date to the birthday of modern cosmology, then it is her.

Strangely enough, it was Scheiply, not Hubble, who suggested astronomers adapt their nomenclature to a new reality and call external star systems “galaxies”. Hubble still enjoyed a conservative view of the world, which he himself had denied. He also naturally preferred to disagree with any ideas filed by his rival, Scheiply. Therefore, Edwin Hubble, the man who proved that the Milky Way is just one of an innumerable multitude of galaxies, never ceased to call these objects "extra-galactic nebulae."

By observing the cyclical fluctuations in the brightness of Cepheids in Andromeda, Hubble expanded the possibilities of the human mind in another way. He saved us from worrying about the fact that the stars distant from us may behave differently than those in our neighborhood. Now that scientists could explore stars in other galaxies, they could determine the constancy of the universe in space and time.

According to modern calculations, the Andromeda galaxy is located 2.5 million light years from us, that is, the visible light started 2.5 million years ago. It turns out that we see the stars of this galaxy not only distant by 2.5 million light years, but also living in 2.5 million years in the past. Nevertheless, they look like the stars closest to us. And when Edwin Hubble and other astronomers looked even further, they added more evidence of spatial and temporal uniformity. In all space and all times, the atoms, apparently, emit the same light, and variable stars obey the same physical laws.

This constancy of nature lent persuasiveness to the search for a single set of rules in effect throughout space. Or, as Albert Einstein would say, showed that God does not change the rules for the existence of the cosmos. It was a damn good birthday present for the human mind.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/401019/

All Articles