Do babies understand the world from birth?

Rebecca Sachs' first son, Arthur, first hit the MRI machine pipe to build a brain scan when he was only a month old. Sachs, a cognitive science specialist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, went there with him. She was uncomfortable lying on her stomach, placing her face next to the diaper of the child, but she stroked and reassured him while the magnet of three tesla was spinning around them. Arthur showed no concern and fell asleep.

All parents are interested in what is happening in the baby’s head, but few have the opportunity to find out. By the time Sachs got pregnant, she had been working with her colleagues for years on developing a scheme for imaging brain activity in babies. But her estimated date of delivery in September 2013 gave the project the momentum needed to complete it.

Over the past 20 years, researchers have used functional MRI to examine the brain of children and adults. But fMRI, like the 19th century daguerreotype, requires complete immobility of the scanned object, or the picture will be smeared. A waking baby is a nervous lump of movements, and it is impossible to persuade or promise them to make them lie still. A small amount of fMRI research that exists today has been done on the basis of brain images of sleeping babies who played music.

')

But Sachs wanted to find out how babies see the world while awake. She needed to get an image of Arthur's brain, looking at video clips. With older subjects it is easy. It was necessary in order to get closer to a more serious question: does the brain of babies work as a miniature copy of the adult brain , or are they fundamentally different? “I have a fundamental question about brain development, and I have a baby with a developing brain,” she says. “The two most important things in my life temporarily merged inside the MRI machine.”

Sachs spent maternity leave, hanging out with Arthur inside the car. “Sometimes he didn’t like it, sometimes he would fall asleep, or be capricious, or get it done,” she says. “It’s rare to get good data on the infant brain.” Between sessions, Sacks and colleagues examined the data, arranged the experiments, looked for patterns in the work of Arthur's brain. When they managed to get the first useful result, Arthur was 4 months old, and Sachs "jumped to the ceiling for joy."

The recent work in Nature Communications is the culmination of more than two years of working with images of Arthur’s brain and eight other babies. In their work, scientists have found unexpected similarities with which the brain of infants and adults responds to visual stimulation, as well as several intriguing differences. This study is the first step on the path that Sachs hopes will be a large-scale attempt to understand the very early stages of the development of the mind.

* * *

fMRI is perhaps the most useful tool, with the exception of opening the skull, which scientists have. It depends on changes in blood flow in the most active areas of the brain, which create a signal detectable by the machine. Technicians also have critics, because this system does not directly measure brain activity, and simple and clear pictures depend on statistical manipulation that takes place behind the scenes of the process. However, fMRI opened up new possibilities, and gave scientists, as Sachs says, a "moving brain map." Scientists have discovered in the smallest detail how different parts of the brain are engaged in staging their activity, depending on what a person does, feels or thinks.

Different areas of the cerebral cortex also perform different tasks. Nancy Kanwisher , a neuroscientist at MIT and former research supervisor, Sachs, opened the “fusiform facial area” area of KGM, which responds more strongly to face images than to other visual stimuli. In her laboratory, they also worked on the opening of the parahippocampal gyrus, responding to images of places. As a graduate student and working in the Kenweiser laboratory, Sax discovered a brain area designed to work with a model of the human psyche (understanding someone else's consciousness) —that is, to process thoughts related to other people's thinking. Since then, several laboratories have already found regions of the brain involved in the analysis of social situations and decision-making.

Sachs, fast-talking and radiant with intelligence, are most concerned with philosophical and fundamental questions about the brain. From her point of view, the next obvious question is: how did the organization of the brain appear? “When you see the rich and abstract functions performed by the brain — the morality, the mental state model — you immediately wonder how it all came about?” She says.

Has the brain evolved in such a way as to separate areas for the most important things for our survival? Or “we are born with an amazing multi-functional toolkit that can learn the organization of the world that it has been given?” Do we come to this world with innate drawings, according to which special areas appear in the brain, for example, for face recognition, or do we develop Are these special areas months or years after we see many faces around us? "The basic structure of the human brain can be similar in all people, because for all people and the world is about the same," she says. Or these basics may be present from birth.

* * *

Riley LeBlanc spits out his nipple and starts yelling. She is five months old, with a pile of wavy brown hair on her head, and she fusses in her diapers, while Heather Kosakowski, laboratory manager Sachs, rocking Riley, stands next to a huge MRT machine on the first floor of the building Department of Brain Research and Cognitive Studies at MIT. Lori Fauci [Lori Fauci], Riley's mother, who sits on the scanner bed, pulls out another baby's dummy from her back pocket.

Here, everything is done so as to reassure Riley. The room is not brightly lit, lullabies are heard from the speakers in the form of tinkling versions of popular songs for a toy piano (at the moment it is Guns N 'Roses, "Sweet Child o' Mine").

Not a toy piano at all, but good performance

On the scanner lounger is a specially designed radio frequency coil - a bedding and a child-sized helmet - which should work as an antenna for radio signals during scanning. The MRI machine is programmed to produce less noise than usual, so as not to damage the delicate hearing of the infant.

After a few false starts, Riley is ready to lie in a reel without fuss. Her mother is lying on her stomach, so that her hands and face are close to Riley and can calm her down. Kozakovski pushes the mother and child into the scanner and goes into the next room, and Lyneé Herrera, another laboratory technician, stays in the room with an MRI and hands Kozakovski to know if Riley’s eyes are open and she looks in the mirror above her head, which displays images projected from the back of the machine.

The goal of the team is to collect 10 minutes of data from each infant, without the movement of the watching video. This is usually enough data collected in two hours of work. “The more often a baby comes to us, the more likely it is to score 10 minutes,” says Kozakovski. This is the eighth visit of Riley.

When Herrera signals that Riley is awake, Kozakowski launches the scanner and launches a set of video clips, since children are more likely to look at moving images than on still images. After a while, Herrera squeezes her fingers, indicating that Riley’s eyes were closed again. “Sometimes it seems to me that our babies sleep best of all,” Kozakovski laughs.

Studying babies always required creativity. “It was an interesting challenge,” says Charles Nelson , a neuroscientist from the Harvard Medical School and the Boston Children's Hospital, who studies development of children, “because you are dealing with a non-verbal, attention-deficient body, and are trying to figure out what happens to in his head. " Sometimes the technology to study babies coincides with the technology to study primate animals, or children with disabilities, unable to speak. “We have a whole range of hidden techniques that allow you to look inside a monkey, baby, or child with developmental problems,” says Nelson.

It is easiest to observe his behavior and mark the direction of his gaze, either through external observation or through technology to track eye movements. You can measure brain activity. For example, for electroencephalography, you only need to attach a helmet with electrodes and wires to the baby's head, and you can remove the fluctuations of brain waves. In the new technology, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR spectroscopy; near near infrared spectroscopy, NIRS), light passes through the soft and thin skull of an infant to help determine changes in the blood circulation of the brain.

Both methods track changes in brain activity, but NIR spectroscopy reaches only the upper layers, and EEG does not show which specific areas of the brain are activated. “In order to study the detailed spatial organization and get to deep parts of the brain, one has to use fMRI,” says Ben Dean , the first author of the study, now working at Rockefeller University.

With the help of other methods, researchers have found hints that babies react differently to visual stimuli of different categories, in particular, to faces. Persons are “a prominent part of the environment,” says Michelle de Haan , a neuroscientist specializing in brain development at University College London. In the first few weeks of life, the baby’s eyes focus best on objects that are within the distance of the face of the nursing mother. Some researchers believe that babies have a congenital mechanism that directs their eyes to their faces.

There is evidence that babies linger on faces for the longest time. With time and experience, the reaction to the face in an infant becomes more specific. For example, it is difficult for adults to distinguish faces upside down, but for babies up to 4 years old there is no such problem - they distinguish inverted faces as well as non-inverted ones. But after 4 months of life, they acquire a tendency to properly located persons. At the age of 6 months, babies who have seen a face will have an ECG similar to the ECG of a person who is examining the face of an adult.

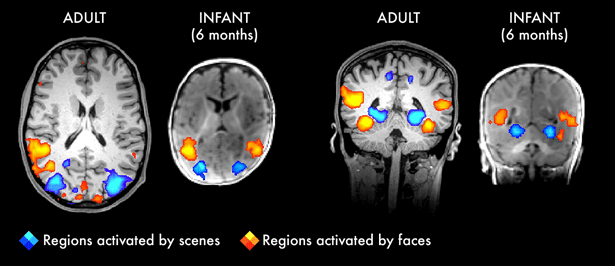

White and blue colors mark regions of the brain that react to the situation. Yellow, orange and red - regions that react to faces

But, according to Dean, although the study claims that there may be a certain specialization for certain categories in the brain of babies, "we have very few details about where these signals come from."

For the current work, Sachs and colleagues received data on nine of the 17 babies scanned by them. And although the laboratory increasingly relies on the help of third parties, they were greatly helped by the “flow of laboratory babies,” including Arthur, the second son of Sachs, Percy, the son of her sister, and the son of a candidate of science. Babies were shown films with faces, images of nature, human bodies, toys, and mixed images that had parts mixed up. Sachs says that those focused on faces, not on the setting, because in the brains of adults, these two reactions are clearly different and occur in very different parts of the brain.

Interestingly, the same pattern was found in infants. “Every region we know, with a preference for responding to faces or environments, also reacts in babies between 4 and 6 months,” says Saks. This shows that the bark "already has a specialization."

Are children born with these opportunities? “You can't strictly say that everything is inborn,” says Dean. "We can say that it develops very early." Sachs notes that these reactions extend beyond the visual cortex. The researchers also found differences in the frontal part of the cortex, which is responsible for emotions, assessment and self-perception. “It’s great to see how babies activate their frontal lobes,” she says. - It is believed that this part is developing one of the last.

However, although the Sachs team found that similar areas of the brain were active in both infants and adults, they did not find evidence that infants have areas that process only one specific type of input, such as individuals or environments. Nelson, who has not worked with this team, says that it follows from this that babies' brains are “more universal.” "This points to the fundamental differences between the brain of an infant and an adult."

* * *

It's amazing how the brain work of babies and adults is similar, considering how much they differ. On the computer screen in the room next to the MRI in MIT, I can see the images of Riley's brain at that moment when she was asleep. Compared to adult brain scans, which show various structures, Riley's brain is frighteningly dark.

“It looks like a bad photo, isn't it?” Kozakowski says. She explains that at this stage in infants the fatty insulation of nerve fibers, the myelin , which makes up the white matter, is underdeveloped. The corpus callosum, a nerve fiber clamp connecting the two hemispheres of the brain, is barely visible.

At this age, the brain is still expanding - in the first year of life, the cerebral cortex swells by 88%. Cells change organization, quickly form new connections, many of which disappear already in childhood and adolescence. At this stage, the brain is amazingly flexible: when children have strokes or seizures that require the removal of a whole hemisphere of the brain , they recover remarkably well. But this flexibility also has limitations; if babies are mistreated, learning deficiencies may remain with them for life.

A study of the development of a healthy brain can help to understand why this process is sometimes distorted. For example, it is known that many children and adults with autism have difficulties with social aspects, for example, with the interpretation of individuals . Are these problems present in the early stages of brain development, or are they part of the children's experience, and caused by a lack of attention to individuals and social subtleties?

We are just beginning to understand the organization of the brain in babies. Building a complete picture of how their brains work will take much more hours to collect data from a much larger number of children. But Sachs and his colleagues showed that such a study is possible, and this opens up new areas for science. “It is possible to get qualitative data from fMRI in awake babies — to be extremely patient,” says Saks. - Now we will try to understand what we can learn thanks to this.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/400937/

All Articles