How to get ice with a temperature of + 151 ° C

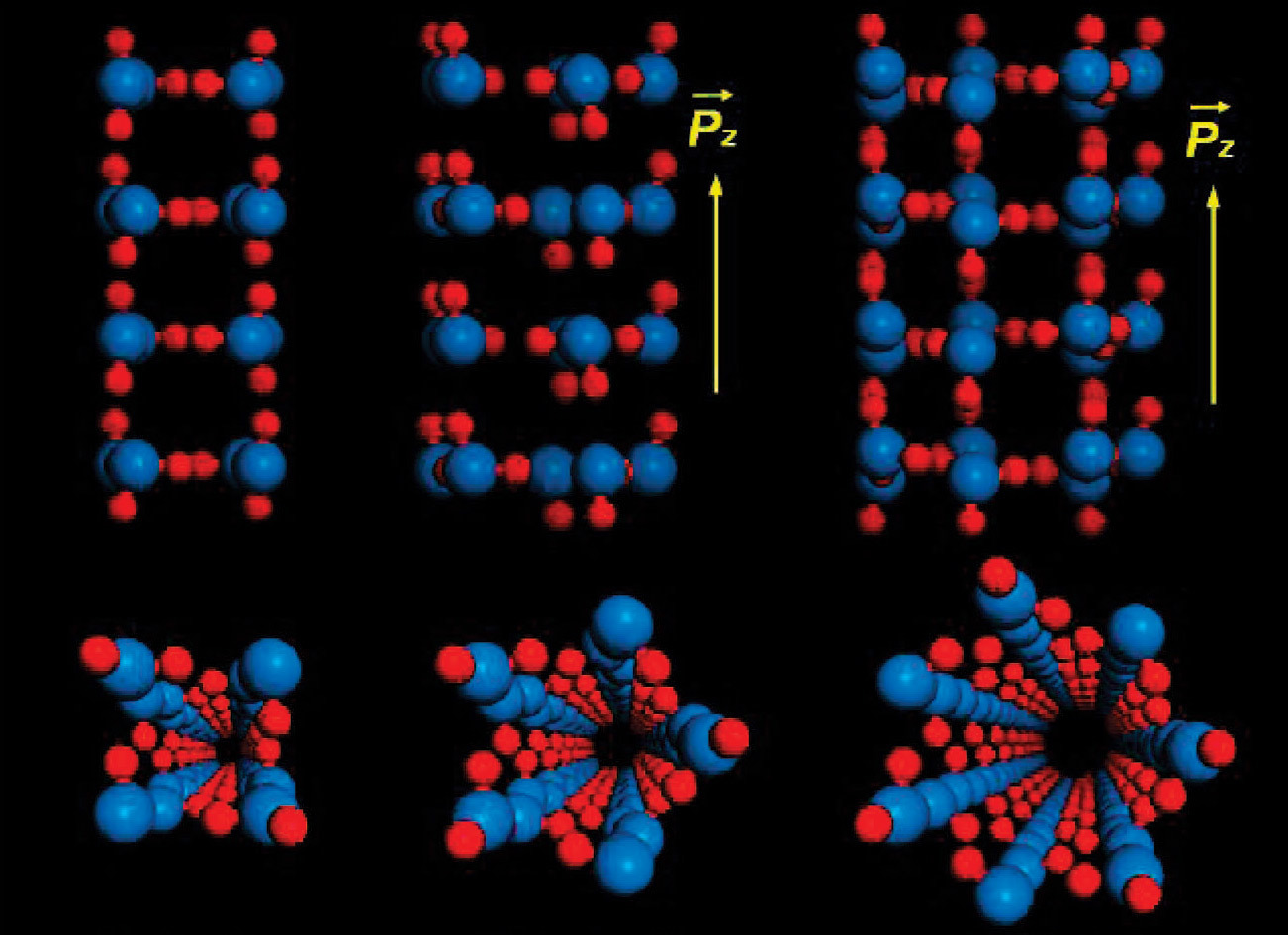

The structure of a quadrangular, pentagonal and heptagonal nanold inside a single-layer nanotube. Blue and red balls correspond to oxygen and hydrogen atoms. Source: 2008 simulation results

The unusual properties of water have long been the object of scrutiny by scientists. Ten years ago, it turned out that inside a nanotube with a diameter of less than 2.5 nm, water does not freeze, but continues to flow even at temperatures close to absolute zero (−273.15 ° C). The oddities do not end there.

The phase transitions of water with the change of the aggregative state inside carbon nanotubes clearly do not fit into the standard theory of thermodynamics. This applies not only to the freezing point, but also to the boiling point. As is known, at normal atmospheric pressure, the boiling point of water is about 100 ° C. As the pressure in the container increases, the boiling point increases - this principle is used by pressure cookers to cook food faster. Conversely, the boiling point of water can be reduced by reducing the pressure. For example, in the mountains at an altitude of 5 km, it is impossible in principle to cook some food, because there the boiling point of water is only 83 ° C due to the reduced atmospheric pressure.

Scientists also know that the temperature of phase transitions of water also depends on the shape and size of the vessel. If the pressure remains unchanged, the boiling point or the freezing point can be shifted by about 10 ° C using the vessel volume. But in carbon nanotubes, everything gets upside down. As already mentioned, water retains a liquid state there at temperatures close to absolute zero. Now scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have investigated in detail another interesting phenomenon - the phase transition to a solid state (ice nanotubes) at high temperature, when under normal conditions the water should evaporate.

')

This phenomenon was discovered in 2001 by a group of Japanese and American scientists. Ice nanotubes are of particular interest because they are formed at high temperatures and can be used in various electronic nanodevices, including gas nanoturbines , flow nanosensors, and high-flux membranes. Moreover, the ability of water to freeze into ice nanotubes at temperatures well above 0 ° C makes it possible to use ice nanotubes in heat transfer systems . Experimental confirmations of such use have been obtained, but until now the exact dimensions and parameters of carbon nanotubes, which are necessary for solidifying water at room temperature and above, have not been studied.

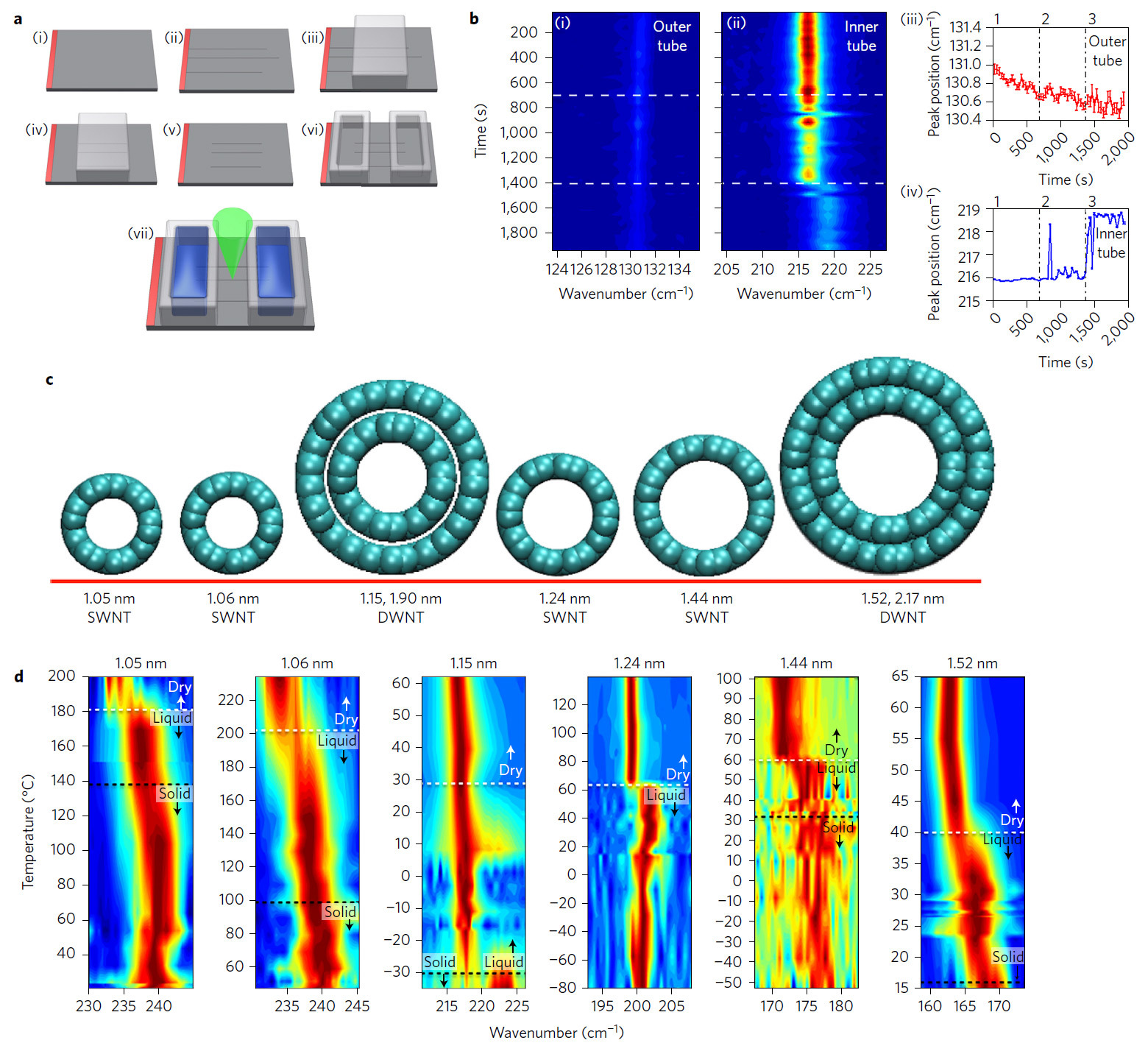

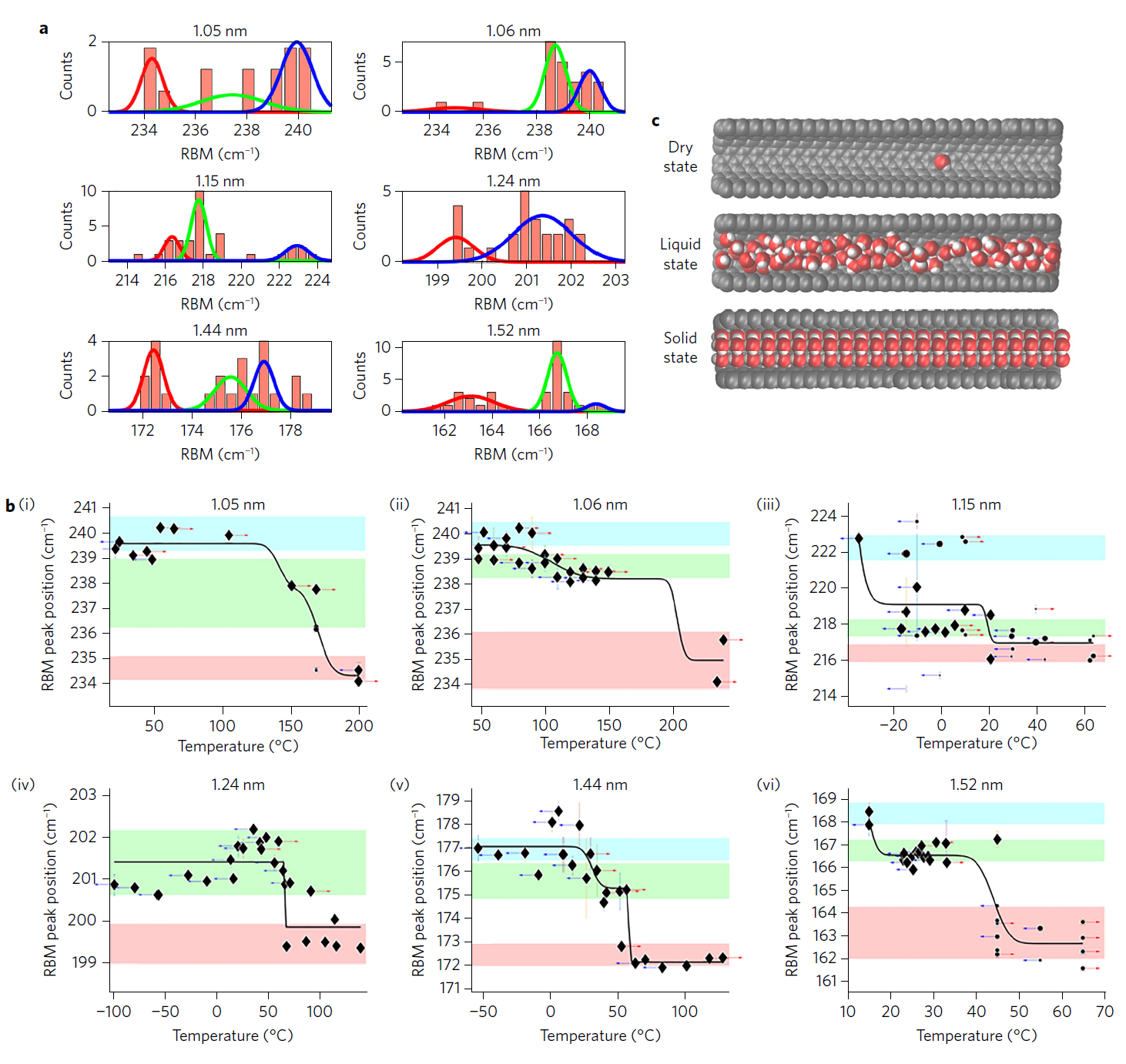

Until now, most of the experiments with the phase transition of water in carbon nanotubes were limited to computer-based molecular dynamics simulations, rather than actual physical experiments. As a result of the simulation, it turned out that the properties of water strongly depend on the diameter of the carbon nanotube. For example, in pores with a diameter of 0.8–1.0 nm, water is well stabilized in the vapor state, and somewhere between 1.1 and 1.2 nm tube diameters simulations show stabilization in the form of ice, that is, in solid form. Then, as the diameter increases above 1.4 nm, stabilization in liquid form again occurs. All this is very interesting - and therefore, MIT developed a methodology for physical experiments to test the properties of water in carbon nanotubes with a diameter of 1.05 to 1.52 nm with single and double walls. The authors of the experiment also developed a technique for monitoring water in nanotubes using Raman spectroscopy (radial oscillations, RBM).

An experimental setup for growing nanotubes and filling them with water (why hydrophobic nanotubes pass water inside - scientists also do not fully understand); computer models of single-layer and two-layer nanotubes for the experiment; Raman spectroscopy results

Experiments have shown that on some diameters of nanotubes, water passes into a solid state of aggregation at temperatures above 100 ° C. The maximum recorded phase transition temperature is from 105 ° C to 151 ° C (more precisely, it could not be measured) with a single-layer nanotube diameter of 1.05 nm. This is much higher than the parameters that the theory predicted . In some cases, the actual freezing point was almost 100 ° C higher than the theory predicted. For the first time, the experiments were carried out in real laboratory conditions - as it turned out, for good reason. No one expected such a big difference in the properties of water in nanotubes with a diameter of 1.05 and 1.06 nm.

The blue color on the diagram is a solid state of water, green is a liquid state, red is empty nanotubes (dry state)

After passing through the freezing point, the scientists lowered the temperature and returned the water to a liquid state, proving the process reversibility. In nanotubes with a diameter of 1.06 nm, ice melted at a temperature of 87–117 ° C, in nanotubes of 1.44 and 1.52 nm, the freezing point is between 15–49 ° C and 3–30 ° C, respectively.

Nano-ice has an interesting combination of electrical and thermal properties. The presence of ice, which does not melt at temperatures up to + 151 ° C, may be of interest to engineers and designers. At room temperature, such ice will be absolutely stable, it is quite possible to use it as wires in electronics and other devices (water is one of the best proton conductors known to science ), which do not heat up to + 151 ° , otherwise this conductor will melt.

The scientific work was published on November 28, 2016 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology (doi: 10.1038 / nnano.2016.254, pdf ).

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/399679/

All Articles