Lithium-ion batteries turned 25 years old. Why in a quarter of a century their active materials have changed so little

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the launch of the first lithium-ion batteries manufactured by Sony in 1991. Over a quarter of a century, their capacity almost doubled from 110 Wh / kg to 200 Wh / kg, but, despite such tremendous progress and numerous studies of electrochemical mechanisms, today chemical processes and materials inside lithium-ion batteries are almost the same as 25 years backwards This article will tell you how the formation and development of this technology went, as well as what difficulties the developers of new materials are facing today.

1. Technology development: 1980-2000

Back in the 70s, scientists found that there are materials called chalcogenides (for example, MoS 2 ), which are capable of engaging in a reversible reaction with lithium ions, embedding them in their layered crystal structure. The first prototype of a lithium-ion battery consisting of chalcogenides at the cathode and metallic lithium at the anode was immediately proposed. Theoretically, during discharging, lithium ions “released” by the anode should be incorporated into the layered structure of MoS 2 , and when charging, settle back to the anode, returning to its original state.

But the first attempts to create such batteries were unsuccessful, since when charging the lithium ions did not want to turn back into a flat plate of metallic lithium, but settled on the anode as it were, resulting in an increase in dendrites (metallic lithium chains), short circuit, and explosion of the batteries. This was followed by a stage of detailed study of the intercalation reaction (incorporation of lithium into crystals with a special structure), which made it possible to replace metallic lithium with carbon: first with coke, and then with graphite, which is still in use and also has a layered structure capable of embedding ions lithium.

A lithium-ion battery with a lithium metal anode (a) and a layered anode (b). Source: nature.com

Starting to use carbon materials at the anode, the scientists realized that nature made humanity a great gift. On graphite, at the very first charge, a protective layer of decomposed electrolyte, called the SEI (Solid Electrolyte Interface), is formed. The exact mechanism of its formation and composition has not yet been fully studied, but it is known that without this unique passivating layer, the electrolyte would continue to decompose at the anode, the electrode would collapse, and the battery would become unusable. Thus, the first working anode based on carbon materials appeared, which was put on sale as part of lithium-ion batteries in the 90s.

Simultaneously with the anode, the cathode also changed: it turned out that not only chalcogenides, but also some transition metal oxides, for example LiMO 2 (M = Ni, Co, Mn), which are not only more stable chemically, have a layered structure capable of embedding lithium ions, but also allow you to create cells with higher voltage. And it was LiCoO 2 that was used in the cathode of the first commercial prototype of batteries.

Source: www.iycr2014.org

2. New reactions and fashion for nanomaterials: 2000-2010

In the 2000s, the nanomaterials boom began. Naturally, progress in nanotechnology has not bypassed lithium-ion batteries. And thanks to them, the scientists made a material that seemed completely unsuitable for this technology, LiFePO 4 , one of the leaders in the use of electromobile batteries in the cathodes.

But the thing is that ordinary, bulky particles of ferric phosphate very poorly carry ions, and their electronic conductivity is very low. But due to lithium nanostructuring, it is not necessary to move long distances to integrate into a nanocrystal, so intercalation is much faster, and coating nanocrystals with a thin carbon film improves their conductivity. As a result, not only less dangerous material, which does not emit oxygen at high temperature (like oxides), but also material having the ability to operate at higher currents, went on sale. That is why such cathode material is preferred by car manufacturers, despite the slightly lower capacity than that of LiCoO 2 .

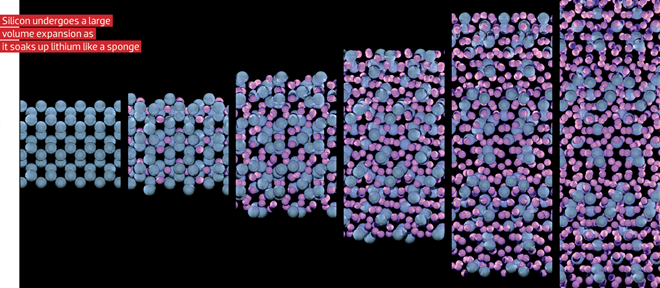

At the same time, scientists were looking for new materials that interact with lithium. And, as it turned out, intercalation, or the incorporation of lithium into a crystal, is not the only reaction on electrodes in lithium-ion batteries. For example, some elements, namely Si, Sn, Sb, etc., form an "alloy" with lithium, if used in the anode. The capacity of such an electrode is 10 times the capacity of graphite, but there is one "but": such an electrode during the formation of the alloy greatly increases in volume, which leads to its rapid cracking and coming into disrepair. And in order to reduce the mechanical stress of the electrode with such an increase in volume, the element (for example, silicon) is proposed to be used in the form of nanoparticles encased in a carbon matrix that “absorbs” volume changes.

Source: chargedevs.com

But the change in volume is not the only problem of the materials forming the alloys, and preventing their widespread use. As mentioned above, graphite forms a "gift of nature" - SEI. And on the materials forming the alloy, the electrolyte decomposes continuously and increases the resistance of the electrode. But nevertheless, from time to time we see in the news that in some batteries a “silicon anode” is used. Yes, silicon is really used in it, but in very small quantities and mixed with graphite so that the "side effects" are not too noticeable. Naturally, when the amount of silicon in the anode is only a few percent, and the rest is graphite, a significant increase in capacity will not work.

And if the topic of anodes, forming alloys, is now developing, then some studies begun in the past decade, very quickly came to a standstill. This concerns, for example, the so-called conversion reactions. In this reaction, some metal compounds (oxides, nitrides, sulfides, etc.) interact with lithium, turning into a metal mixed with lithium compounds:

M a X b ==> aM + bLi n X

M: metal

X: O, N, C, S ...

And, as you can imagine, during the course of such a reaction, such changes occur with the material that even silicon did not dream of. For example, cobalt oxide is converted to cobalt metal nanoparticles enclosed in a matrix of lithium oxides:

Source: J. Phys. Chem C 117, 14518 (2013)

Naturally, such a reaction is poorly reversible, besides between charging and discharging a large voltage difference, which makes such materials useless in the application.

It is interesting to note that when this reaction was discovered, hundreds of articles on this topic were published in scientific journals. But here you want to quote Professor Tarascon from Collège de France, who said that "conversion reactions were a real field of experimentation for studying materials with nanoarchitecture, which allowed scientists to make beautiful pictures using a transmission electron microscope and publish in well-known journals, despite the absolute practical the futility of these materials. "

In general, to sum up, despite the fact that in the last decade hundreds of new materials for electrodes have been synthesized, almost the same materials used 25 years ago are used in batteries. Why did this happen?

3. Present: the main difficulties in developing new batteries.

As you can see, in the above excursion into the history of lithium-ion batteries, not a word was said about another, the most important element: electrolyte. And there is a reason for this: the electrolyte has remained almost unchanged for 25 years and there have been no proposed alternatives. Today, as in the 90s, lithium salts (mainly LiPF 6 ) are used in the form of electrolyte in an organic solution of carbonates (ethylene carbonate (EC) + dimethyl carbonate (DMC)). But precisely because of the electrolyte, the progress in increasing the capacity of batteries in recent years has slowed.

I will give a concrete example: today there are materials for electrodes that could significantly increase the capacity of lithium-ion batteries. These include, for example, LiNi 0.5 Mn 1.5 O 4 , which would allow the battery to be made with a cell voltage of 5 volts. But alas, in such voltage ranges, the electrolyte based on carbonates becomes unstable. Or another example: as mentioned above, today, in order to use significant amounts of silicon (or other metals forming alloys with lithium) in the anode, one of the main problems must be solved: the formation of a passivating layer (SEI) that would prevent the continuous decomposition of electrolyte and the destruction of the electrode, and for this it is necessary to develop a fundamentally new electrolyte composition. But why is it so difficult to find an alternative to the existing composition, because lithium salts are full, and there are enough organic solvents ?!

And the difficulty lies in the fact that the electrolyte must simultaneously have the following characteristics:

- It must be chemically stable while the battery is running, or rather, it must be resistant to the oxidizing cathode and the reducing anode. This means that attempts to increase the energy consumption of the battery, that is, the use of even more oxidizing cathodes and regenerating anodes, should not lead to the decomposition of the electrolyte.

- The electrolyte should also have good ionic conductivity and low viscosity to transport lithium ions over a wide range of temperatures. For this, DMC has been added to viscous ethylene carbonate since 1994.

- Lithium salts should be well dissolved in an organic solvent.

- The electrolyte must form an effective passivating layer. In ethylene carbonate, this is excellent, while other solvents, such as propylene carbonate, which was originally tested by Sony, destroy the structure of the anode, since it is embedded in it in parallel with lithium.

Naturally, to create an electrolyte that has all these characteristics at once is very difficult, but scientists do not lose hope. First, there are active searches for new solvents that would work in a wider range of voltages than carbonates, which would allow the use of new materials and increase the power consumption of batteries. Several types of organic solvents are under development: esters, sulfones, sulphoxides, etc. But alas, increasing the resistance of electrolytes to oxidation decreases their resistance to recovery, and as a result, the cell voltage does not change at all. In addition, not all solvents form a protective passivating layer on the anode. That is why special additives are often added to the electrolyte, for example, vinylene carbonate, which artificially contribute to the formation of this layer.

In parallel with the improvement of existing technologies, scientists are working on innovative solutions. And these solutions can be reduced to trying to get rid of liquid carbonate-based solvent. These technologies include, for example, ionic liquids. Ionic liquids are essentially molten salts that have a very low melting point, and some of them remain liquid even at room temperature. And all this is due to the fact that these salts have a special, sterically hindered structure, which will complicate crystallization.

Source: www.eurare.eu

It would seem a great idea to completely eliminate the solvent, which is highly flammable and enters into parasitic reactions with lithium. But in fact, the exclusion of the solvent creates at the moment more problems than it solves. First, in conventional electrolytes, part of the solvent "sacrifices itself" to build a protective layer on the surface of the electrodes. And the components of ionic liquids cannot cope with this task yet (anions, by the way, can also enter into parasitic reactions with electrodes, like solvents). Secondly, it is very difficult to choose an ionic liquid with the correct anion, since they affect not only the melting point of the salt, but also the electrochemical stability. And alas, the most stable anions form salts, which melt at high temperatures, and, respectively, vice versa.

Another way to get rid of carbonate-based solvent is to use solid polymers (for example, polyesters) that conduct lithium, which, firstly, would minimize the risk of electrolyte leakage to the outside, and also prevent dendrites from growing by using metallic lithium at the anode. But the main difficulty facing the creators of polymer electrolytes is their very low ionic conductivity, since lithium ions find it difficult to move in such a viscous medium. This, of course, severely limits the power of the batteries. A decrease in viscosity entails the germination of dendrites.

Source: www.polito.it

The researchers also study solid inorganic substances that conduct lithium with the help of defects in the crystal, and try to apply them in the form of electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. At first glance, such a system is ideal: chemical and electrochemical stability, resistance with increasing temperature and mechanical strength. But these materials, again, have very low ionic conductivity, and it is reasonable to use them only as thin films. In addition, these materials work best at high temperatures. And finally, with solid electrolyte it is very difficult to create a mechanical contact between the electrolyte and the electrodes (in this area, liquid electrolytes have no equal).

4. Conclusion.

Since the release of lithium-ion batteries for sale, attempts to increase their capacity have not ceased. But in recent years, the increase in capacity has slowed, despite the hundreds of new materials proposed for electrodes. And the thing is that the majority of these new materials "lie on the shelf" and wait until a new electrolyte suitable for them appears. And the development of new electrolytes, in my opinion, is a much more difficult task than the development of new electrodes, since it is necessary to take into account not only the electrochemical properties of the electrolyte itself, but also all its interactions with the electrodes. In general, reading news such as "a new super-electrode has been developed ..." it is necessary to check how such an electrode interacts with an electrolyte, and whether there is a suitable electrolyte for such an electrode in principle.

Sources:

Electrochem. Soc. Interface Fall 2016 volume 25, issue 3, 79-83

Chem. Rev., 2014, 114 (23), pp 11503–11618

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/399107/

All Articles