75,000 futures

The global stock market has become an artificially created world inhabited by algorithms and exotic financial instruments. The scale of the economic rivalry of these creatures and the speed of their actions are beyond the limits of which the human mind can grasp. But, in companies that analyze markets, there are people who look like zoologists who systematize new biological species. They, like detectives, are looking for traces that algorithms leave among the market data. They build graphics, as Linnaeus painted animals and plants, make lists of strange and beautiful images, and, looking at them, often give them names. "75,000 Futures" is a project of Gunnar Green and Bernd Hopfengartner , inspired by the desire to understand new forms of digital "life."

Sasha Pokhlepp

When Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz arrived in London in 1673, he was immediately surrounded by a crowd of people on the London Bridge. These people were not interested in German science. What they needed was news about the Dutch war, which Leibnitz or his companions could find out during the trip. Leibniz, to the delight of others, was very talkative. And while he was sharing rumors and observations, some people decided that he had learned enough.

“One pushed through the stairs, and a crowd of bouncing barefoot boys immediately surrounded him. The gentleman quickly wrote something on a piece of paper and gave it to a boy who jumped higher than the others. He made his way through the crowd of comrades, soared up the stairs through three steps, jumped over the cart, shoved the fish vendor and ran over the bridge. From here to the coast was a hundred and something yards and about six hundred more to the Stock Exchange - at a pace of about three minutes. ”

To an inexperienced observer this scene from Neil Stevenson’s novel Mercury may seem like a game, but what we see here happens for purely economic reasons. Valuable information is exchanged for money on the London Stock Exchange. Leibniz then told the crowd that he had heard the shots, but he also added - already after the boy ran away, that these were not simple shots: “ Rare. Most likely these were signals. The encrypted information spread through the fog, so impenetrable to light and so transparent to sound ... "

')

On March 2, 1791, about eighty years after Leibniz’s death, the Frenchman Claude Chappe invented and created the first working system for optical transmission of messages over distances. “If you succeed, you will be covered with glory,” the system was successfully tested on this text. The invention was called the telegraph.

By 1830, there were already about 1000 telegraph towers throughout Europe. With their help it was possible, for example, to send messages from Paris to Amsterdam or from Brest to Vienna. At the peak of the prevalence of new means of communication, in 1850, only the French telegraph system covered 29 cities. It consisted of 556 stations, the telegraph network stretched about 4,800 kilometers. For all this to work, good visibility was needed. If there was a fog, nothing could be transmitted over the optical telegraph.

Nowadays, to conduct business operations "in thick fog" is a common thing. Trading algorithms are constantly competing with each other, chasing profits over underground cables of global networks. Financial instruments are bought in some places, where their price is lower, in order to sell on the site where they are more expensive. And so - until the price in different places is equal.

Sometimes there is a direct interdependence between assets: for example, if the price of crude oil goes up, it is highly likely that the value of the shares of oil companies will rise. If the algorithm wants to make money, it must be faster than its comrades in the workshop. So far, everything is simple. However, the matter becomes more complicated if the algorithms not only try to work as quickly as possible, but also watch the rivals, and try to hide the signs of their actions from them, while trying to identify patterns in the behavior of other algorithms.

Algorithms of digital trading systems have long been something more than just a set of rules regarding the purchase and sale of shares. They study everything around in search of correlations, driven by the need to adapt to the environment, they are becoming faster and more complex.

Getting close to understanding some things is possible only when they stop working properly or break. Worldwide racing trading algorithms, usually invisible to non-professionals, attracted widespread attention on May 6th, 2010. Then there was an "instant collapse" of the market, one of the sharpest collapses in the history of the American stock exchange. It was caused by the algorithmic sale of 75,000 E-mini futures. The market recovered very soon, but precedent is important: for the first time, high-frequency trading was associated with similar events. It lasted only a few minutes, but in order to understand the cause of the incident, the researchers needed years.

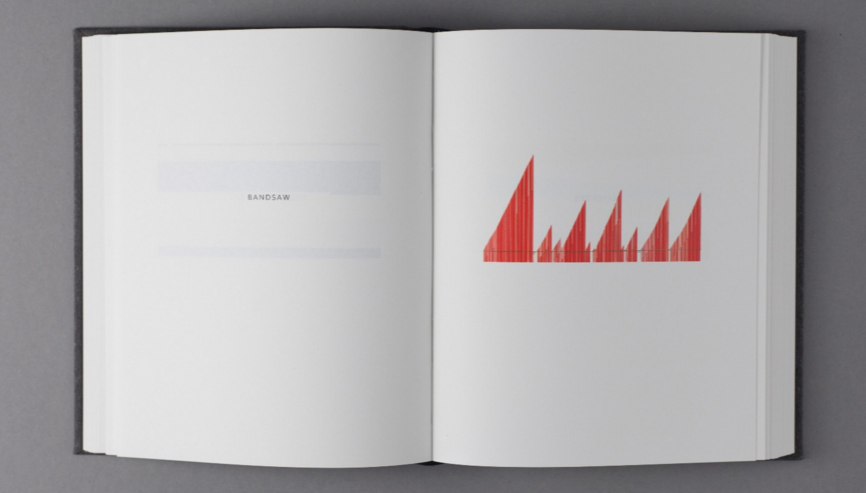

It must be said that not every unusual market activity can be quickly noticed. Algorithm trading causes microscopic price fluctuations in millisecond ranges, these fluctuations resemble staccato that a person does not play. Thus, usually, at the time of their occurrence, unusual actions go unnoticed. Nanex specializes in the study of historical trade data. In the course of such studies, unusual samples of interesting algorithmic trading sequences were identified and collected. They were posted on the site and gave them the names: "Castle Wall", "To the moon, Alice!", "Sunshowers", "Broken Highway".

From an economic point of view, these charts are still inexplicable. We cannot read them as an open book, but this does not mean that they are useless. They are like Dadaist poems, when the main thing is form, rhythm, color, and not content. The names of the graphs turn them into pictures. Here, for example, "Castle Wall", or "Fortress Wall". In the mind of the one who sees the chart and reads the name, the crazy round dance of the strokes slowly turns into fortress walls. Of course, there are no walls here, they are the product of our imagination and the desire to understand them, by relating them to what we are familiar with.

Probably, the graphics are hints of what the world of algorithms looks like. After all, algorithms - in fact, they are very similar to us. When, driven by a thirst for success, they go through the fog, night birds may seem to them robbers and monsters. Fantasy sometimes plays evil jokes with those who have it. Just like us, the algorithms set their own order and establish connections, create pictures and see what is not. If the person and the algorithm rested on the lawn and looked at the sky, then both of them would see faces in the outlines of the clouds. It seems to us that the collapse of the market in 2010 is not only financial, but also a semiotic problem.

We consider graphics, but we do not understand them. “They are beautiful,” we think. With every movement of the line, millions of dollars pass from hand to hand. The only thing that can be stated with confidence is that the graphs reflect certain events. But where exactly and how exactly they happened is a mystery.

Our book, inspired by the beauty of graphs, is trying to enhance the effect that their contemplation causes. We have removed all unnecessary. There are no names of financial instruments, no time stamps or numeric values. There are only abstract images. Color, shape, space.

We have collected, on several hundred pages, traces of algorithms left by them in time. We have a kind of catalog of rarities. Our task is not to identify or classify finds. The most important thing is to show the life of the algorithms.

Looking again at these images, we realized that now they speak to us differently than before. There are no more graphs of mysterious functions or recorder curves. Instead, we see unknown landscapes, space travel, sunsets and sunrises. This is 75,000 futures.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/398175/

All Articles