Loss of the eleventh day of the month and other dates

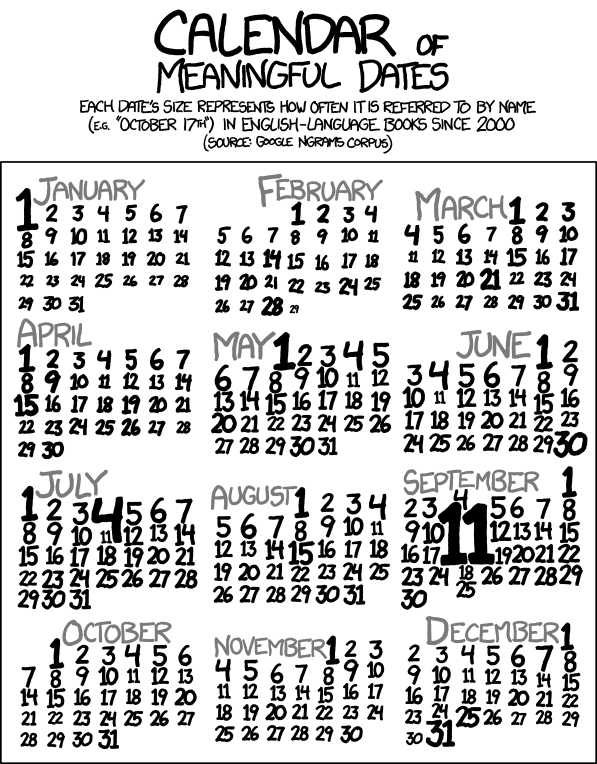

In November 2012, Randal Monroe published the xkcd comic with a calendar in which the size of the numbers of each month was proportional to how often this number is mentioned in books by its name (for example, "October 14th") in the Google Ngrams database since 2000. Most of the big dates are pretty obvious: July 4, December 25 , the first day of every month, the last day of almost all the months, well, September 11 , leaving everyone behind. Not so many days looks much less than the rest. For example, February 29 is a tiny point. But if you look closely, you can see that the 11th of each month is relatively small. There was a note to the comic book: “In all the others, except September, months, the 11th is mentioned less often than other dates. It was the same until September 11 [2001], and I don’t know why this is so. ” I rummaged in the data, and I think I figured out why.

At first I made sure that the 11th is different from the rest. A month can be up to 31 days, and some of these days are sure to be the smallest of all. Maybe the 11th on the calendar is not the smallest, just our eye clings to it. So I compared the real data, and not just studied the comics. The Ngrams database returns the total number of times the phrase is mentioned for the year, normalized by the number of books published that year.

I chose the number of each day of the year (January 1, January 2) and built the medians by month for each day of the month (January 1, February 1, etc.) for each year. This showed how often the 11th and 30 other days are mentioned in the selected year. The median allows you to smooth out bursts from the July 4th type days. A median will look unusual only if the sequence number is very different in at least 6 of 12 months.

')

I built the medians for each serial number from 2000 to 2008. Below is a histogram for 31 medians. The first number stands out from all, and 15 is barely visible among the rest. But the result of the 11th is the least of all by a fairly large amount (with a P-value <0.05), which at first glance is difficult to explain.

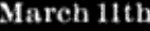

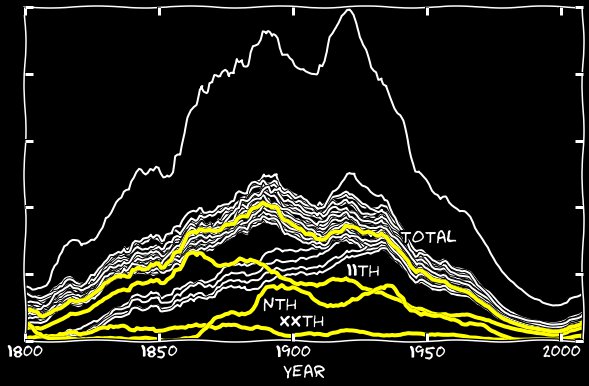

And this deficiency has existed for a long time. In the following graph, all the sequence numbers for each of the years of the span of 1800–2008. The data is smoothed over 11 years to remove noise. Even at the very beginning the 11th is much lower than the main group. Its small flaw persists for several decades, and then in the 1860s the 11th suddenly deviates from its position as the last in the series of averages. The gap between the 11th and ordinary ordinal numbers increases sharply, and as a result, the value for the frequency of its mentionings becomes about half lower, which continues in the first half of the 20th century. In the second half, the gap narrows, but does not disappear to the very end.

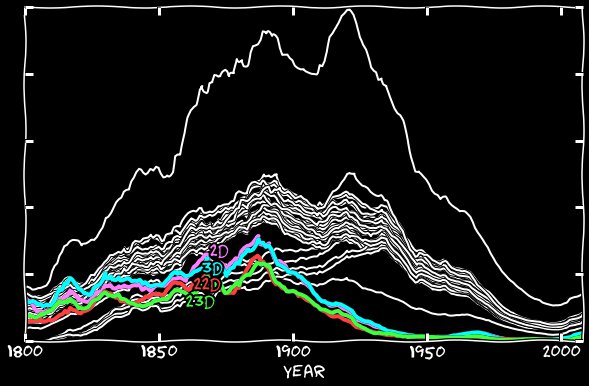

Attentive readers will notice another oddity. There are 4 more lines that are lower than they should be. Top down is the 2nd, 3rd, 22nd and 23rd numbers. From 1800 to 1890, they are even lower than the 11th. But from 1900 their gap shrinks, while the gap from the 11th begins to widen, and disappears completely by 1930. This is also quite an interesting topic, which we will discuss later.

Typographic oddities

Starting research, I hoped to find a secret taboo on the events of the 11th or typographical deviation from the rules of printing. Alas, the reason turned out to be much more mundane: the number 1 is very similar to the uppercase I (i) or lowercase l (L) in most fonts used to print books. And also 11 can be confused with n. Algorithms from Google are wrong, recognizing 11 on the page, and interpret the sequence number as a kind of word.

We can directly search for meaningless phrases such as ll March or II July or ii May. 11 can be confused with nine combinations of I, l and i. Five of them are actually found in the database, at least for one month: II-th, Il-ny, ii-ny, li-ny and ll-ny. Also there were options with only one wrong character, 1l-ny, 1i-ny and l1-ny. I called these errors xxth. Google Books makes inquiries to a newer database than Ngrams, but examples of such errors can still be found. For example , Google recognizes the following as January II:

Like February February :

But li mar:

There are plenty of such examples in the database. You can find other mistakenly interpreted sequence numbers, but the 11th is much more common.

I added January II, January January, etc., to my calculations, and did the same for the other months. The following chart shows that the 11th gets a big boost from this addition. Until the 1860s, the difference between the 11th and the main group disappeared. After the 1860s, a third or a quarter of this difference disappeared.

And what happened to the rest of the 11th? From the 1860s, the Google algorithm begins to err in a strange way: instead of 11, it recognizes n-n. Here is an example of a page filled with the nth January numbers:

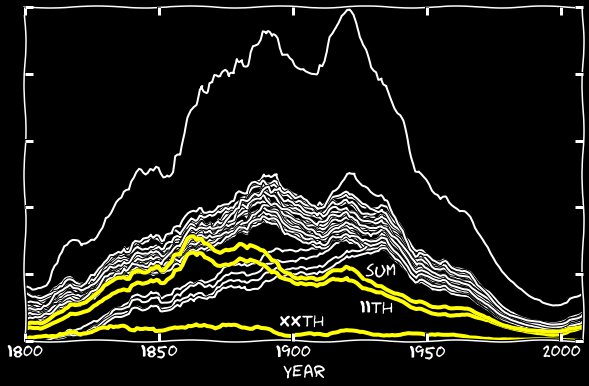

In some years, the number of incorrect recognitions exceeds the number of correct ones. I added the nth number of January to the 11th of January, and did the same with the other months. The following graph shows both the n'th numbers and their sum with the 11th. Until the 1860s, their contribution was insignificant, but then this error begins to be responsible for almost all the missing 11th.

Combined schedule

Adding xxth and nth errors to the 11th chart, I fixed the gap along the entire length of the graph, and the 11th began to look the same as all the other dates. It turns out that the incorrect recognition of the 11th in the form of the nth, II, ll, and so on, is responsible for a small number of 11 numbers among the other days of the month.

Typographic machines

Although it is clear why the 11th was more often recognized incorrectly, why the number of errors is so uneven? What happened in the 1860s because of what the percentage of errors jumped so much? I suspect that this is due to the invention of a device such as a typewriter in the 1860s. The earliest typewriters did not have a separate key for the number 1 . It was proposed instead to use the letter l (L) in lowercase. And when the algorithm recognizes the llth of October, it actually does it more correctly than we thought. There are not so many typed documents in Google books, but this popular device has greatly influenced the development of fonts. 1 and l did not differ on the increasingly widespread typewriters, and even typographical font began to justify the expectations of this similarity. Compare these characters in the 1850 font:

Visible difference between l without a serif at the top and 1 with a clear serif. Compare them in 1920 font:

The characters are identical, with the exception of kerning. And today, most of the fonts represent 1 and l in the form of tall characters with two serifs at the bottom and one directed to the left, at the top. Only the angle of serif 1 is slightly larger than that of l. The print quality of books since 1970 helps to reduce the number of misrecognitions, but they have not completely disappeared, so the remaining problems appeared on the xkcd comic.

The question of the popularity of an error, in which 11 is replaced by the n-th, remains open. This is a rather strange mistake. The n-th is often found in mathematics and scientific publications, and this may affect its popularity. In most fonts, the upper part of n is very thin, and probably may not be visible in the texts on which the algorithm was trained. But there is a big difference in growth of 1 and n, especially in the era of typewriters, where many errors occur. But the phrase n-January is nonsense, so the chances of such recognition should have decreased. Perhaps some modern texts contained errors, and in them the 11th were marked as n-ny, which was the source of errors? The only way to find out is to open the source code of a text recognition algorithm from Google. This exercise we will leave to the reader.

Loss of 2, 3, 22 and 23

We figured out the 11 numbers, but during the study of their behavior, I ran into another mystery - an incomprehensible low number of 2, 3, 22 and 23 numbers, but only until the 1930s, after what their number is aligned.

On the chart below are all the numbers, and it appears that in the 1800s these dates are not used at all. The first mentions of our dates appear in the 1810s, their number grows at the same speed as other dates, but at the same time it maintains a gap with them - their number is approximately two times less. Suddenly, the gap widens in the 1890s, and this happens until the 1930s, when they finally merge into the main group.

Prerevolutionary style

So, the numbers 2 and 3 in the nineteenth century were unhappy? Algorithm from Google hardly recognized twos and triples in old fonts? No, it turns out that earlier instead of the current English record “2nd, 3rd, 22nd, 23rd” it was customary to write “2d, 3d, 22d, 23d”. I built the median for January 2d, February 2d and other months, and did the same with the remaining dates. The graph below shows the frequency of the appearance of these dates in the old style of recording - they begin with the frequency of other dates, but then gradually disappear by 1890, and completely dissolve by 1930.

Sometimes it is possible to meet the modern use of the old record form, if it is used in a name with a long history, such as 3d Marine Division. But the residual use of such a record is mainly due to the existence of reprints of old books and publications of old diaries.

Combined schedule

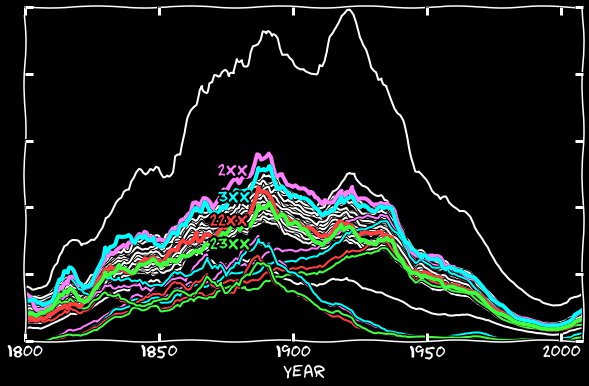

If we add the old style to the new, we get the following graph. It follows from it that correctly calculated dates are almost indistinguishable from all the others.

Why now it turns out that the mention of 2 and 3 numbers sometimes exceed the rest in frequency, it remains incomprehensible to me. I think that because of the too frequent mentioning on the 1st of the month, the 2nd and 3rd should also be mentioned a little more often. But if you search Google Books for the occurrences of January 2d or January 2nd, you can find quite a few similar passages:

Apparently, Google Books ignores commas. So, although the dates of the month from 1 to 4 do not represent anything special, such examples here can affect the statistics.

Reasoning

Why did the writers used such single letter abbreviations before? Perhaps because of Latin, where the sequence number indicator was the letter o. In such Romance languages as Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, are still used o or a. We would still use d if it were not for 1st, 4th, etc., in which the last consonant is not expressed in English in one letter. It turned out that following the English language outweighed the desire to imitate Latin.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/397869/

All Articles