The use of calligraphy and other educational myths

One woman, a newcomer to a group of home education adherents that our family also attends, said that one of the disappointments that led her to take her son out of the school system was that he was not allowed to write stories at school. He loves to do it, and it is rather strange that the school impedes his enthusiasm. But the teacher declared that he was not ready for this, as he had not yet mastered calligraphy.

As for me, it serves as a symbol of incomprehensible obsession, shared by many countries, about how children should learn to write. We teach them to form letters based on what they see in the primers. And then we force them to learn this skill anew, only by continuous writing. However, there is no evidence of the advantages of italics over other writing styles, for example, over a manuscript in which letters are not connected, for the majority of normally developed children.

')

I'm not talking about a letter by hand as such, which is often associated with italics. There is ample evidence that handwriting develops cognitive abilities in a way that a seal cannot do: it is worth teaching. I confess that I myself am rather old-fashioned, and I think that good handwriting is the right and necessary skill, not only for cases when the laptop battery sits down, but also to express your personality and character. I will also say that italics is a good thing, sometimes beautiful, and children should have the opportunity to teach it, in the case of time and inclination. My elder loves italics and he has a very beautiful handwriting, which I am proud of. And I like Victorian calligraphy.

But to force to learn calligraphy from an early age is another matter. There must be a reason for this, as well as for everything else that children teach. But calligraphy stubbornly remains one of the objects only because of a mixture of traditionalism, educational inertia, folklore, prejudice and bribes. It seems that what the teachers “know” about how children should learn is the result of culture, not the data of the research. Scrapbook training is hardly so unique in educational practice. What causes the question: what about the evidence?

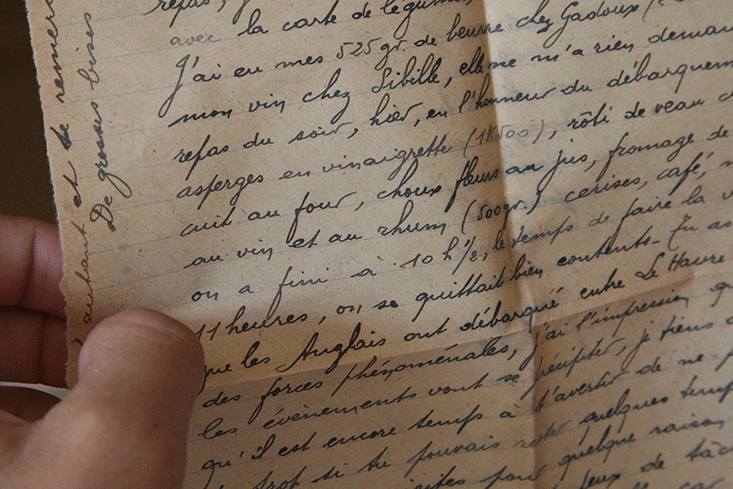

Modern italics appeared in the Renaissance Italy, perhaps in order not to tear the delicate pen from the paper once again in order to avoid damage to it and splashing of ink. By the 19th century, calligraphic handwriting was associated with good education and character. Teaching children a letter in which letters are not joined together began only in the USA in the 1920s. In many countries, children are usually taught to write in separate letters in the first grade, and then in one letter in the second or third. In France, children should write in italics right from the kindergarten, and in Mexico they teach only writing in separate letters. Variants are possible in the United States and Britain, but it has been suggested that italics should become the usual method of writing for students. Learning italics can be forced, and students are under-graded if they write wrong. In France, the italic form is universal and standardized, and children are not recommended to develop their own writing style.

Despite such a scatter, calligraphy training often takes place under the auspices of correctness. Just need to do. If you ask the teachers why - they will look at you strangely, and then they will give you answers, among which may be the following:

• So write faster.

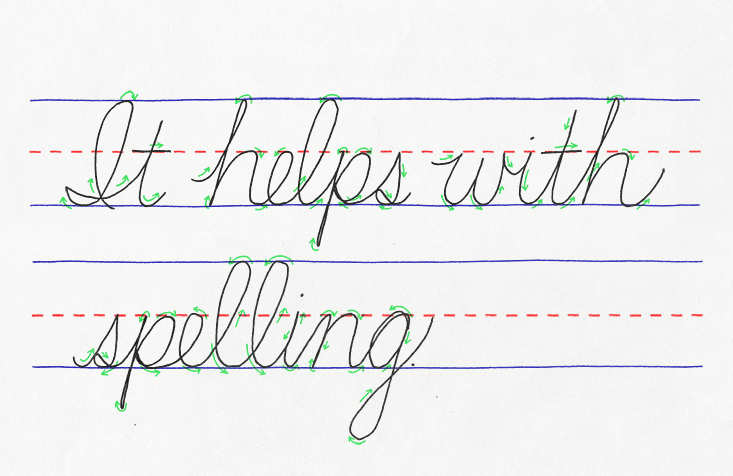

• It helps to write correctly.

• It helps with dyslexia.

What do the studies say? And they could not find any evidence of the benefits of italics over other forms of writing. “There is no convincing evidence of the benefits of studying italics for the cognitive development of children,” says Karin Harman James, associate professor in the Department of Psychology and Neurology at Indiana University, who studies brain development under the influence of learning.

James warns that this issue is very difficult to study, since it is difficult to find children whose education would differ only in the style of writing. Moreover, most of the evidence is rather old and of dubious quality, and some of the discoveries are also contradictory. Simply put, our understanding of how children react to different styles of writing is surprisingly fragmentary and terribly inadequate.

Consider what we know. Many people, including teachers, swear that italics are faster to write, and refer to the fact that they do not need to tear the pen from the paper, and to their own experience. Of course, the last argument sounds as if I declared that English is faster than French, because I can write and speak it faster. Naturally, this is the case when you have been doing something all your life.

The past writing speed tests were inconclusive. One of the best and most recent was held in 2013 by Florence Bar, now working at the University of Toulouse in France, and Marie-France Morin from the University of Sherbrooke in Canada. They compared the writing speed of francophone pupils in their countries. And although in France they are forced to teach italics, in Canada they are more liberal about this. Some Canadians first learn a separate letter, and then - merged, some immediately learn to write together.

And was the merged letter faster? No, it was slower. The fastest of all was a personal mixture of separate and consistent letters, appearing by itself among students in grades 4-5. Even in France, a quarter of students abandoned italics for the 4th grade for the sake of mixed style. They learned a separate writing style thanks to reading books, despite the fact that they were taught differently.

And although on average italics turned out to be slower, this style was more legible than that of the students, who were taught only separate writing. But the mixed style allows you to write faster, while almost keeping up with legibility.

Bara and Maureen made recommendations on teaching a particular writing style, and only mentioned that it would be unwise to insist on any of the styles. This idea is supported by Virginia Berninger [Virginia Berninger], a professor of psychology at Washington University. “The evidence supports the practice of teaching both writing styles, after which the student himself chooses the most suitable way for him,” she writes in her 2012 paper.

Does italics help deal with problems like dyslexia? There is some evidence. “Some children who have a hard time coping with printed text are helped to learn italics, because they may not tear the pencil from paper too often,” says James. And he adds, "these children are rather an exception, and these results cannot be generalized for all."

In the case of ordinary children, there is reason to believe that separate writing has its advantages. Italics are more complex to coordinate movements, its letters are also more complicated, and some studies from the 1930s and 1960s say that children learn to write earlier and more legibly using separate letters. They often have to tear the pen from the paper, so they can better prepare for the next letter. Some studies suggest that the release of recognition resources spent on the removal of complex cursive forms helps children to write more precisely and expressively.

There is also an opinion that the difference in the appearance of letters can slow down the development of reading skills, and it will be harder for children to transfer skills between reading and writing, since there is no italics in books. Reading and Literacy Expert Randall Wallace of the University of Missouri says: “It would be strange if the first readers, who were used to recognizing split letters, would be offered to learn another writing style.”

But it is not clear how much these difficulties manifest themselves in practice. In a 2009 study in Quebec, Bar and Maureen did not find reading problems in elementary school students related to italics. And in their later study, comparing Canadian and French elementary school students, they found that those who taught only italics coped with letter recognition and corresponding sounds worse than those who taught both italics and separate writing.

Regardless of the importance and duration of these differences, it seems logical that they should be. There is evidence, both behavioral and neurological, that tactile familiarity with the shapes of letters helps early reading skills, indicating a connection between motor skills and visual letter recognition. This, by the way, is one of the reasons why it is important to teach children to write by hand, and not just type on the keyboard.

But the difference between the letter forms is much less clear. In a study on brain scanning in older children, James did not observe "the difference between the two writing styles." The type of letter does not affect tactile feedback and reinforcement skills, as long as the children draw the letters themselves, and do not lead the pen along the lines.

In general, it remains to be decided what it is better to teach children - separate writing, merged, or both forms at once. In all cases, there may be pros and cons. And even if learning to both styles reveals advantages, it is not clear whether it will be possible to spend time and class resources in a more productive way.

Why do some educational systems attach so much importance to studying italics? How, if not addressing the evidence, is a learning policy formed?

“It seems to me that cursive is taught because of the tradition and demands of the parents, and not because there is some scientific basis for its benefits,” Wallace says. The bad thing is that inertia and prejudice distort perceptions and rules through scientific evidence.

In 2011, Bar and Maureen decided to study the work of the teachers in more detail. They interviewed 45 teachers in Quebec and France, asking how and why they teach penmanship.

The results were sobering. The teachers had only fragmentary knowledge about scientific research, especially regarding the aspects of motility in writing. Their views were shaped by culture and educational institution.

While the views of Canadian teachers on which form of letter is harder to teach, were divided, the French were unanimous. Four-fifths of them insisted that italics are no more difficult than separate letters, and 3/4 said that italics are faster — which is refuted by research. More than half of teachers in Quebec believed that when studying separate letters it would be easier to learn to read, and in France only 10% share this opinion.

In other words, the teachers, whom their Ministry of Education recommends to teach in italics, are convinced that there are grounds for that. And teachers in Canada, who solve these questions themselves, believe that there are grounds that justify their decisions.

The lack of rational arguments for calligraphy suggests that emotions are involved. My previous article for the British magazine, where I condemned the hegemony of italics, received the maximum number of responses in its entire history. A couple of popular arguments in defense of italics:

Imagine the frustration of your children when they find the letters of the grandmothers in the attic and cannot read them! Without italics, you deprive them of their past.

Italics are beautiful, and the separate letter looks like children's scribbles.

Italic is not another language. You can learn to read it in an hour. And how many people keep grandmother's letters in graceful italics in the attic? I like the original manuscripts of Jane Austen, but it is clear that most people have italics far from perfect. And the childishness of a separate letter depends on the observer.

Beliefs in favor of italics resemble the hydra - cut off one head, grow another. Take an article in The New York Times from 2014 about the pros and cons of penmanship. She refers to a study from 2012 that allegedly shows that italics can help children with dysgraphia, letter disorder, associated with difficulty in controlling motor skills while writing; It can prevent the writing of letters in reverse. It is stated so often that I decided to go deeper into it.

I found a job as education researcher Diane Montgomery [Diane Montgomery], describing a study that used Cognitive Process Strategies for Spelling (CPSS) to help students with writing problems that are usually diagnosed as dyslexia. In this method, children are taught in italics, and no comparisons are made with other writing styles.

Montgomery explains the choice of italics by saying that experiments with children were successful, and that italics were used in other projects, but he cites only one “evidence”. This is a study from 1998, where, according to Montgomery, it is reported that "italic text, apparently, contributes to speed writing." At the same time, this statement is not only contrary to the work of Bar and Maureen, but he is not even actually in the work of 1998. There it is simply reported that the acceleration of the letter slightly worsens his intelligibility.

Montgomery also quotes a work from 1976 that allegedly advocates “exclusive use of italics from the very beginning.” And again there is no such thing at all. It describes a study comparing the education of children who confused order and writing letters, which they immediately taught in italics, with the education of children with writing problems, who were first taught separate writing. The first ones, as a result, began to make slightly less mistakes, but the author himself admits that due to the smallness of the sample, these data cannot be considered proof of the superiority of a merged letter over a separate letter.

This is how it is. But at the same time, many people will be convinced that the benefits of italics are confirmed by The New York Times. No wonder teachers got confused.

Debate over writing styles should be held, but definitely not in schools and ministries of education. And every time when I find out that a student is undervalued for the lack of perfect motility, or forbidden to express himself only because he does not use acceptable handwriting, I see that our unfounded obsession with italics is not only meaningless, but also destructive.

The question arises: what else in education is determined by the belief that “right” is not supported by evidence? Education and training is difficult to evaluate in research. Teaching practices change, and it is often impossible to define control groups. But often it is precisely the absence of solid objective evidence that makes one rely on incomprehensible dogmas. This is dangerous in education, since any topics related to the upbringing and development of children are subject to emotional judgments.

Some evidence exists. But the teachers practically do not listen to them, and more importantly, the regulators. Too often, education turns into political football. In 2013, former Education Minister Michael Gove was hated by teachers in Britain for imposing educational rules on his ideas. He rejected the advice of experts, which became clear from his interview when he stated that “in this country, experts are already tired of everything”. And this disregard for research results is not limited by policy; training and education are influenced by all ideologies.

It is necessary to examine how strongly scientific evidence affects education. Are we looking closely enough at them? Or is children's learning more dependent on precedents and cultural norms? Judging by the calligraphy, everything is very bad.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/397699/

All Articles