10% of wildlife destroyed in 25 years. Well done people

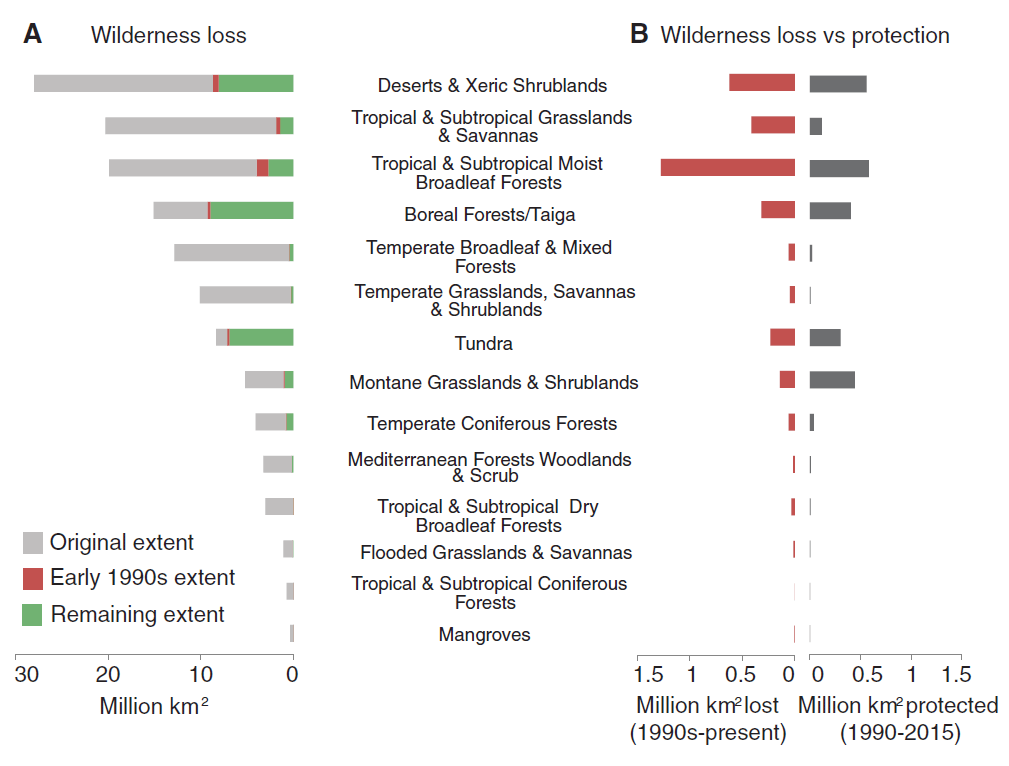

The change in the area of untouched nature from the early 1990s to 2015 (light red and light green), including on “globally significant” large areas of more than 10 000 km 2 (dark red and dark green)

People are actively changing the Earth’s ecosystem for several centuries . Nevertheless, there are still relatively untouched wilderness areas on the planet, where ecological and evolutionary processes take place with minimal human participation. These wilderness areas are exceptionally important to humanity as critical bastions that maintain species diversity , bind and store excess CO 2 , soften and regulate climate . Despite this, the wilderness areas are almost completely ignored by the global political establishment, these areas almost never enter into international agreements on environmental issues. It is believed that wildlife is relatively safe from the destructive activity of people. Therefore, it is not a priority object of security activity. This is a big mistake.

A group of scientists from the University of Queensland in Brisbane (Australia), the environmental organization Wildlife Conservation Society (USA), University. James Cook, University. Griffith (both - Australia) and the University of Northern British Columbia (Canada) published a scientific paper in which this thesis is disputed. They made comparative maps of areas of wildlife on Earth as of 1993 and 2015, using the method of assessing human influence on the environment, which takes into account population density, changes in the landscape (river beds, coast, roads and railways), power lines, etc. According to the accepted methodology, Antarctica and other ecoregions covered with stones, ice and “lakes” were excluded from the map of untouched nature.

According to this methodology, wildlife now occupies 30.1 million km 2 or 23.2% of the Earth’s land and is predominantly located in North America, North Asia (Siberia), North Africa and Australia.

')

Since the beginning of the 1990s, the planet has lost 3.3 million km 2 of untouched nature, that is, approximately 9.6% of the total.

The reduction of intact areas also affects the “globally significant” areas of untouched nature - these are areas of more than 10,000 km 2 . 74% of large natural blocks underwent similar erosion. As a result, 37 out of 350 large areas of wild nature that are globally significant for humanity have gone beyond the lower limit of 10,000 km 2 in area and are no longer considered globally significant. The world's largest natural block, Amazonia, has decreased from 1.8 million km 2 to 1.3 million km 2 . In 3 of the 14 terrestrial terrestrial biomes, there are no areas of untouched nature left over 10,000 km 2 .

It should be noted that "untouched nature" does not mean the complete absence of man. Quite the contrary, many wilderness areas are the most important conditions for the survival of small indigenous peoples. These tribes do not spoil the environment at all, they can even contribute to increasing the natural diversity .

Scientists have noted the threatening rate of a decrease in the total area of untouched nature around the world by about 10%, especially in the Amazon (by 30%) and Central Africa (by 14%).

The authors of the scientific work draw attention to the fact that over the same time period from the 1990s to our time, there has been an increase in environmental protection activity. But it does not help. The diagram shows that the area of lost wilderness almost everywhere exceeds the area of protected areas. Globally, 3.3 million km 2 is lost, and 2.5 million km 2 is under protection

It can be concluded that this activity does not bring results: either people are trying to protect not something that really needs protection, or our efforts are not enough.

Environmentalists urge the immediate adoption of international agreements that postulate the global significance of the untouched nature and the unprecedented threat to which it is exposed. We need to act quickly and globally.

It is known that the forest on Earth binds a significant part of terrestrial carbon. About 1950 petagrams of carbon (1 950 000 000 000 tons) are associated in plants. This is more than in the atmosphere (598 Pg), coal (446 Pg), gas (383 Pg) and oil (173 Pg). Only Amazonia accounts for 228.7 Pg of carbon. Conservation of forests, especially in pristine natural areas, is very important for stabilizing the atmospheric concentration of CO 2 .

Wild regions need protection from people, otherwise it could catastrophically affect CO 2 emissions. For example, due to human fires in Borneo and Sumatra in 1997, more than 1 Pg of CO2 was emitted into the atmosphere, which is approximately 10% of the average annual emissions of man-made mankind into the atmosphere during the anthropogenic era.

If we talk about the ensuing anthropocene epoch, when human activity affects many systemic processes on Earth, untouched natural territories also serve as natural laboratories in which we can study the ecological and evolutionary influence of global changes that occur due to man’s fault. This is a kind of “control points” with which you can compare other areas where intensive development and exploitation of land for the needs of civilization continues.

As large areas of pristine ecosystems become less common, their value increases. The loss of wildlife is an important global problem with highly unpredictable consequences for humans and nature, scientists believe. If nothing is done, and the current trend continues, then by the end of this century, the Earth may remain untouched corners of nature with an area of more than 10,000 km 2 .

Proactive protection of the remaining wildlife regions on Earth is the only way out. “You cannot restore wildlife. If it has disappeared, if the ecological processes that support these ecosystems have ended, then they can never be returned to their original state. The only way out is proactive defense, says James Watson of the University of Queensland, one of the authors of the study. “We must act for our children and their children.”

The scientific work “Catastrophic Declines in Wilderness Areas Undermine Global Environment Targets” was published in the journal Current Biology (doi: 10.1016 / j.c.2016.2016.08.049).

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/397343/

All Articles