Medieval weapons and armor: common misconceptions and frequently asked questions

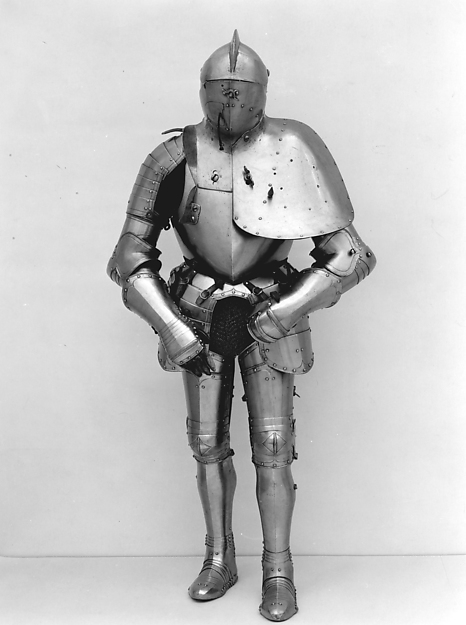

German armor of the XVI century for the knight and horse

The area of weapons and armor is surrounded by romantic legends, monstrous myths and widespread delusions. Their sources are often lack of knowledge and experience in dealing with real things and their history. Most of these ideas are absurd and not based on anything.

Perhaps one of the most notorious examples would be the opinion that “knights on horses should have been planted with a crane”, which is as absurd as popular opinion even among historians. In other cases, some technical details that defy the obvious description have become the object of passionate and fantastic in their ingenuity attempts to explain their purpose. Among them, the first place, apparently, is the emphasis for the spear, which protrudes from the right side of the breastplate.

')

The following text will try to correct the most popular misconceptions, and answer questions frequently asked during tours of museums.

Misconceptions and questions about armor

1. Armor was worn only by knights.

This erroneous but widespread opinion probably derives from the romantic notion of “a knight in shining armor,” a picture that in itself causes further misconceptions. First, the knights rarely fought alone, and the army in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance did not consist entirely of mounted knights. Although the knights were the dominant force of most of these armies, they were invariably - and over time all the more strongly - supported (and opposed them) by infantrymen, such as archers, pikemen, crossbowmen and soldiers with firearms. In the campaign, the knight depended on a group of servants, squires and soldiers who provided armed support and watched his horses, armor and other equipment, not to mention the peasants and artisans who made feudal society with the existence of the military class possible.

Armor for a knightly duel, the end of the XVI century

Secondly, it is wrong to believe that every noble person was a knight. Knights were not born, knights were created by other knights, feudal lords or sometimes priests. And under certain conditions, people of noble origin could be knighted (although knights were often considered the lowest rank of nobility). Sometimes mercenaries or civilians who fought as ordinary soldiers could be knighted because of the demonstration of extreme courage and courage, and later it became possible to purchase knighthood for money.

In other words, the ability to wear armor and fight in armor was not the prerogative of the knights. Marines from mercenaries, or groups of soldiers consisting of peasants, or burghers (city dwellers) also took part in armed conflicts and, accordingly, defended themselves with armor of different quality and size. In fact, burghers (of a certain age and above a certain income or wealth) in most cities of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance were obliged — often by law and decrees — to buy and store their own weapons and armor. Usually it was not a one-piece armor, but at least it included a helmet, body protection in the form of chain mail, cloth armor or breastplate, as well as a weapon — a spear, pike, bow, or crossbow.

17th Century Indian Mail

In wartime, this militia was obliged to protect the city or perform military duties for feudal lords or allied cities. During the 15th century, when some rich and powerful cities began to become more independent and presumptuous, even the burghers organized their own tournaments, in which they, of course, wore armor.

In this regard, not every piece of armor was ever worn by a knight, and not every person depicted in armor would be a knight. A man in armor would be more correct to be called a man-at-arms soldier or a man in armor.

2. Women of old never wore armor or fought in battles.

In most historical periods there is evidence of women involved in armed conflict. There is evidence of how noble ladies became military commanders, for example, Jeanne de Pentevr (1319–1384). There are rare references to women from lower society who have risen "under the gun." There are records that women fought in armor, but no illustrations of that time on this subject have been preserved. Jeanne d'Arc (1412–1431) is perhaps the most famous example of a female warrior, and there is evidence that she wore armor ordered for her by the French king Charles VII. But only one small illustration came to us with her image, made during her life, on which she is depicted with a sword and a banner, but without armor. The fact that contemporaries perceived a woman commanding an army, or even wearing armor, as something worthy of record, says that this spectacle was the exception, not the rule.

3. Armor was so expensive that only princes and rich noble gentlemen could afford it.

This idea could have been born from the fact that most of the armor exhibited in museums is of high quality equipment, and much of the simpler armor that belonged to ordinary people and the lower noble ones was hidden in the vaults or lost over the centuries.

Indeed, with the exception of mining armor on the battlefield or winning a tournament, the purchase of armor was a very expensive enterprise. However, since there are differences in the quality of the armor, differences in their value should have existed. The armor of low and medium quality, available to burghers, mercenaries and the lower nobility, could be bought off-the-shelf in markets, fairs and in city stores. On the other hand, there was a high-class armor, custom-made in the imperial or royal workshops and the famous German and Italian gunsmiths.

The armor of the king of England, Henry VIII, XVI century

The armor for the authorship of some of the most famous masters was the highest achievement of the art of armory and were extremely expensive.

Although examples of the cost of armor, weapons and equipment in some of the historical periods have reached us, it is very difficult to translate the historical cost into modern analogues. It is clear, however, that the cost of armor varied from low-cost, low-quality or outdated, second-hand items available to citizens and mercenaries, to the cost of the full armor of the English knight, which in 1374 was estimated at £ 16. It was analogous to the cost of 5-8 years of renting a merchant's house in London, or three years of salary for an experienced worker, and the price of a helmet alone (with visor, and probably with a barmitsa ) was more than the price of a cow.

At the upper end of the scale you can find such examples as a large set of armor (the main set, which with the help of additional items and plates could be adapted for various applications, both on the battlefield and in the tournament), ordered in 1546 by the German king (later - Emperor) for his son. In fulfillment of this order, for the year of work, court armorer Jörg Seuzenhofer from Innsbruck received an incredible amount of 1,200 gold coins, equivalent to the twelve annual salary of a senior court official.

4. Armor is extremely heavy and severely limits the mobility of its carrier.

Thanks for the tip in the comments on the article.

A full set of combat armor usually weighs from 20 to 25 kg, and a helmet from 2 to 4 kg. This is less than the full equipment of a firefighter with oxygen equipment, or the fact that modern soldiers have to be worn in battle since the nineteenth century. Moreover, while modern equipment usually hangs from shoulders or belts, the weight of well-fitted armor is distributed throughout the body. Only by the XVII century, the weight of combat armor was greatly increased to make them bulletproof, due to the increased accuracy of firearms. In this case, full armor began to occur less and less, and only important parts of the body: the head, torso and arms were protected by metal plates.

The opinion that wearing the armor (established by 1420-30) greatly reduced the mobility of a warrior is not true. Equipment lat was made of separate elements for each limb. Each element consisted of metal plates and plates connected by movable rivets and leather straps, which made it possible to perform any movements without restrictions imposed by the stiffness of the material. The common perception that a man in armor could barely move, and falling to the ground, could not rise, has no reason. On the contrary, historical sources tell about the famous French knight Jean II Le Mengre, nicknamed Busico (1366–1421), who, dressed in full armor, could, grasping the steps of the ladder from below, from the back of her side, climb it with the help of some hands Moreover, there are several illustrations of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, on which soldiers, squires or knights, in full armor, climb horses without outside help or any devices, without ladders and cranes. Modern experiments with real armor of the 15th and 16th centuries and with their exact copies showed that even an untrained person in a properly selected armor can climb and dismount from a horse, sit or lie, and then get up from the ground, run and move limbs freely and without inconvenience.

In some exceptional cases, the armor was very heavy or held the person wearing them in almost the same position, for example, in some types of tournaments. Tournament armor was made for special occasions and worn for a limited time. A man in armor then climbed a horse with the help of a squire or a small ladder, and the last elements of armor could be worn on him after he had settled in the saddle.

5. Knights had to be saddled with cranes

This idea, apparently, appeared in the late nineteenth century as a joke. She entered popular fiction in subsequent decades, and this picture was eventually immortalized in 1944, when Lawrence Olivier used it in his film King Henry V, despite the protests of historical advisers, among whom was such an eminent authority as James Mann, chief gunsmith of the Tower of London.

As stated above, most of the armor was light and flexible enough to not hold down the carrier. Most people in armor should have been able to put one foot in the stirrup without any problems and ride the horse without help. A stool or a squire's help would speed this process. But the crane was absolutely not needed.

6. How did people in the armor go to the toilet?

One of the most popular questions, especially among young visitors to the museum, unfortunately, does not have an exact answer. When a man in armor was not engaged in a battle, he did the same thing that people do today. He would have gone to the toilet (which in the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance was called a lavatory or latrine) or to another secluded place, filmed the appropriate parts of armor and clothing and indulged in the call of nature. On the battlefield, everything had to be different. In this case, the answer is unknown to us. However, it should be noted that the desire to go to the toilet in the heat of the battle was most likely at the end of the list of priorities.

7. Military salute originated from the gesture of raising the visor

Some believe that a military salute appeared in the days of the Roman Republic, when murder by order was in the order of things, and citizens approaching the officials needed to raise their right hand to show that there was no hidden weapon in it. A more common opinion is that modern military salute came from people in armor who raised their helmets before greeting their comrades or lords. This gesture made it possible to recognize the person, and also made him vulnerable and at the same time demonstrated that there was no weapon in his right hand (which usually held a sword). All these were signs of trust and good intentions.

Although these theories sound intriguing and romantic, there is practically no evidence that the military salute came from them. As for the Roman customs, it would be almost impossible to prove that they lasted fifteen centuries (or were restored during the Renaissance), and led to a modern military salute. There is also no direct confirmation of the theory with the visor, although it is later. After 1600, most military helmets were no longer equipped with visors, and after 1700 rarely anyone wore helmets on European battlefields.

One way or another, the military records of 17th century England reflect that "the formal act of greeting was the removal of the headdress." By 1745, the English regiment of the Coldstream Guard, apparently, had improved this procedure, transforming it into “putting a hand to the head and bowing at the meeting.”

Coldstream Guard

This practice was adapted by other British regiments, and then it could spread to America (during the War of Independence) and continental Europe (during the Napoleonic Wars). So the truth may be somewhere in the middle, in which a military salute originated from a gesture of respect and courtesy, in parallel with the civil habit of raising or touching the edge of a hat, perhaps with a combination of the warrior custom of showing the unaided right hand.

8. Mail - "chain mail" or "mail"?

German Mail XV century

Protective attire, consisting of intertwined rings, in English should correctly be called "mail" or "mail armor". The generally accepted term “chain mail” is a modern pleonasm (a linguistic error, meaning the use of more words than is necessary for a description). In our case, the “chain” (chain) and “mail” describe an object consisting of a sequence of intertwined rings. That is, the term “chain mail” simply repeats the same thing twice.

As in the case of other misconceptions, the roots of this error should be sought in the XIX century. When those who began to study armor looked at medieval paintings, they noticed, as they thought, many different types of armor: rings, chains, bracelets made of rings, scaly armor, small plates, etc. As a result, all the old armor was called “mail”, distinguishing it only in appearance, from which the terms “ring-mail”, “chain-mail”, “banded mail”, “scale-mail”, and “plate-mail” appeared. Today, it is considered that most of these different images were only different attempts by artists to correctly reflect the surface of that type of armor, which is difficult to capture in a painting and in sculpture. Instead of depicting individual rings, these details were stylized with dots, strokes, flourishes, circles, and other things, which led to errors.

9. How long did it take to make full armor?

Definitely answer the question is difficult for many reasons. First, evidence has not been preserved that can draw a complete picture for any of the periods. From about the 15th century, scattered examples of how armor was ordered, how long it took to order, and how much different parts of armor cost, have survived. Secondly, a full armor could consist of parts made by various gunsmiths with a narrow specialization. Parts of the armor could be sold in an unfinished form, and then for a certain amount to fit in place. Finally, the case was complicated by regional and national differences.

In the case of the German gunsmiths, most of the workshops were controlled by strict guild rules, which limited the number of students, and thus controlled the number of items that one master and his workshop could produce. In Italy, on the other hand, there were no such restrictions, and workshops could grow, which improved the speed of production and the quantity of products.

In any case, it is worth bearing in mind that the production of armor and weapons flourished in the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance. Gunsmiths, manufacturers of blades, pistols, bows, crossbows and arrows were present in any large city. As now, their market depended on supply and demand, and effective work was a key parameter for success. The common myth that making simple chain mail took several years was nonsense (but it cannot be denied that making chain mail was very labor-intensive).

The answer to this question is simple and elusive at the same time. The time of making the armor depended on several factors, for example, on the customer, on who was charged with making the order (the number of people in production and the employment of the workshop with other orders), and the quality of the armor. Two famous examples will serve us as an illustration.

In 1473, Martin Rondel [Martin Rondelle], possibly an Italian gunsmith who worked in Bruges, who called himself “the gunsmith of my bastard Burgundy,” wrote to his English client, Sir John Paston. The gunsmith informed Sir John that he could fulfill the request for the manufacture of armor, as soon as the English knight tells you which parts of the suit he needs, in what form, and the time by which the armor should be completed (unfortunately, the gunsmith did not indicate possible deadlines ). In the court workshops, the production of armor for higher persons, apparently, took more time. The court armorer Jörg Zoysenhofer (with a small number of assistants), making armor for the horse and large armor for the king, took, apparently, more than a year. The order was made in November 1546 by the king (later the emperor) Ferdinand I (1503–1564) for himself and his son, and was executed in November 1547. We do not know whether Zeuzenhofer and his workshop worked at that time on other orders.

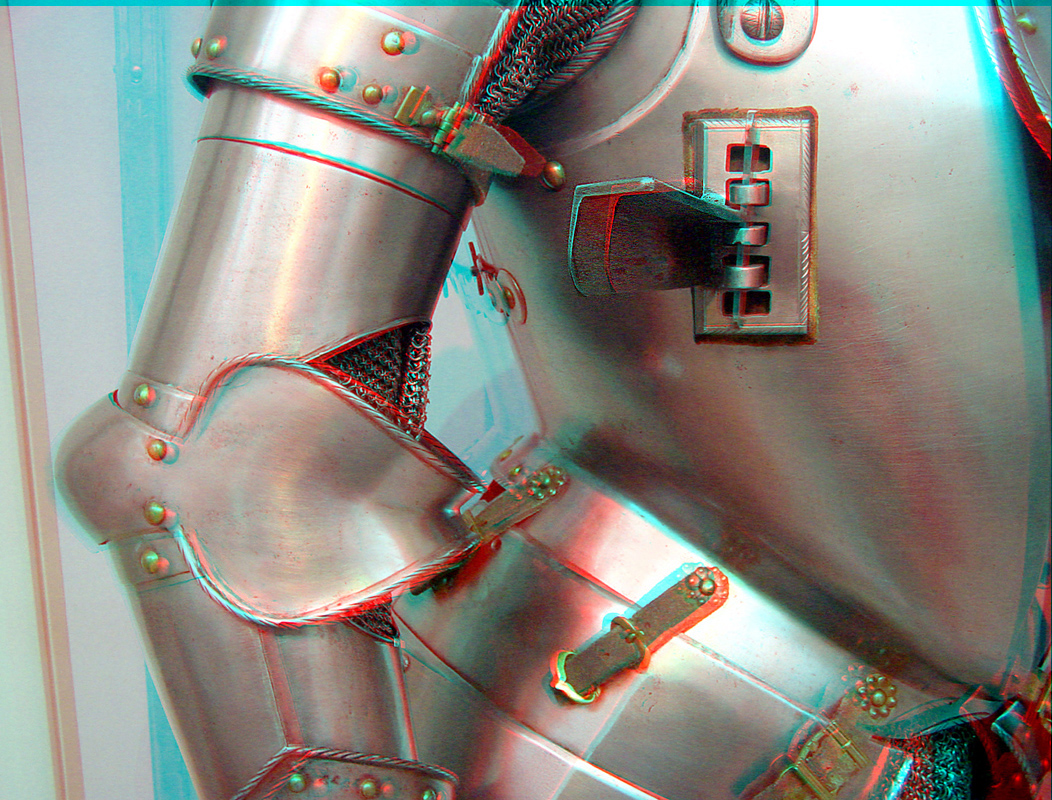

10. Details of armor - support for a spear and a codpiece

Two details of the armor inflame the public’s imagination more than others: one of them is described as “that thing sticking to the right of the chest”, and the second is mentioned after a muffled giggle, as “that thing between the legs”. In the terminology of weapons and armor, they are known as a support for a spear and a codpiece.

The support for the spear appeared shortly after the appearance of a solid chest plate at the end of the XIV century and existed until the armor began to disappear. In contrast to the literal meaning of the English term “lance rest” (spear stand), its main purpose was not to assume the weight of the spear. In fact, it was used for two purposes, which are better described by the French term “arrêt de cuirasse” (spear restraint). She let the supreme warrior hold her spear tightly under her right arm, restricting him from sliding backwards. This made it possible to stabilize the spear and balance it, which improved the sight. In addition, the overall weight and speed of the horse and rider were transferred to the tip of the spear, which made this weapon very formidable. If they hit the target, the support for the spear also worked as an absorber of the blow, preventing the “shot” of the spear back, and distributing the blow to the chest plate over the entire upper part of the body, and not just the right arm, wrist, elbow and shoulder. It is worth noting that on most combat armor the support for the spear could be folded up so as not to interfere with the mobility of the hand holding the sword after the warrior got rid of the spear.

The history of the armored codpiece is closely connected with his sister in civilian male costume. From the middle of the XIV century, the upper part of men's clothing began to shorten so much that it ceased to cover the crotch. In those days, pants were not yet invented, and men wore leggings, fastened to underwear or a belt, and the crotch was hidden behind a hollow, attached to the inside of the upper edge of each leggings. At the beginning of the XVI century, this floor began to fill and visually enlarge. And the codpiece remained a detail of a men's suit until the end of the 16th century. The codpiece on the armor as a separate plate protecting the genitals appeared in the second decade of the 16th century, and remained relevant until the 1570s. She had a thick lining inside and joined the armor in the center of the bottom edge of the shirt. The earliest varieties were cup-shaped, but due to the influence of civilian costume, it gradually transformed into an upwardly shaped form. It was not usually used when riding a horse, because, firstly, it would interfere, and secondly, the armored front of the saddle provided sufficient protection for the perineum. Therefore, the codpiece was usually used for armor intended for foot battles, both in war and in tournaments, and, despite some value as a defense, it was no less used for fashion.

11. Did the Vikings wear horns on their helmets?

One of the most stable and popular images of a medieval warrior is the image of a Viking, which can be instantly recognized by a helmet equipped with a pair of horns. However, there is very little evidence that the Vikings ever used horns to decorate their helmets.

The earliest example of the decoration of a helmet with a pair of stylized horns is a small group of helmets that has come down to us from the Celtic Bronze Age, found in Scandinavia and on the territory of modern France, Germany and Austria. These decorations were made of bronze and could take the form of two horns or a flat triangular profile. These helmets date from the XII or XI century BC. After two thousand years, from 1250, a pair of horns gained popularity in Europe and remained one of the most frequently used heraldic symbols on helmets for battle and tournaments in the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance. It is easy to see that these two periods do not coincide with what is usually associated with Scandinavian raids that took place from the end of the 8th to the end of the 11th centuries.

Viking helmets were usually conical or hemispherical, sometimes made from a single piece of metal, sometimes from segments fastened together by strips (Spangenhelm).

Many such helmets were equipped with face protection. The latter could take the form of a metal bar covering the nose, or a face sheet consisting of the protection of the nose and two eyes, as well as the upper part of the cheekbones, or the protection of the entire face and neck in the form of chain mail.

12. Armor was no longer needed due to the appearance of firearms.

, - , , - . XIV , XVII , 300 . XVI , , .

XIV

, , . , , , , , , . , , - .

13. ,

, , , , 150 . XV XVI .

, , . -, , , , ? -, , , , 2-5 , ( ) () .

, , ( ), ( «»). , , , , , , .

, , I, (1515–47), VIII, (1509–47). 180 , , , .

, XVI

I, XVI

Metropolitan Museum , 1530 , I (1503–1564), 1555 . , , . , , 193 , – 137 , 170 .

14. , .

, ( XIV XV , — XV—XVI , XVI ) , , . – , , , , .

, , . , , .

, XV

, XVI

, , , . , – , . , .

. . « » ( ), , , . (, ) - . – – , . , , , .

, , . - , XV XVI , – , . XIX .

, , , , « », , . . - . . – , .

. 1-2 , « » XIV-XVI 4,5 . , , . , , .

, XVIII

, XV

, , , , . «». , , , , . , , , , .

, , , , , . . , , , . , « ».

, , . -, . -, , , . , () , , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/397045/

All Articles