Pain medications that can stop an opioid crisis

Perhaps researchers will soon be able to save us from pain, without causing addiction and other destructive side effects.

Every time James Zadina publishes a new work or press reference, the phone in his lab in New Orleans starts ringing. Emails overflow the box. Messages come from people from all over the country complaining of pain.

')

“They call me and say,“ I have such terrible pains. When will your medicine appear? “, Says Zadina. And I answer “I can’t give it to you now, I work as fast as I can”. That's all I can say. But it is difficult".

For the past 20 years, Zadina, a researcher at the University of Tullein Medical School and the Veterans Health System of Southeast Louisiana, is at the forefront of the battle with the ancient enemy of humanity: physical pain. Recently, his work has gained new urgency. In the United States, opioid mortality and attachment rates are reaching epidemic proportions and Zadina is trying to create a new type of pain medication that does not have such devastating side effects that often prescribed drugs like Oxycodone have.

His search is complicated by the fact that the very same mechanisms that allow drugs to effectively neutralize pain are responsible for addiction and drug abuse. Just like their close chemical cousin, heroin, opioids can cause physical dependence in people. For decades, researchers have been trying to “separate opioid addictive and analgesic properties,” says David Thomas, administrator at the State Institute for Drug Dependence and one of the founders of the Pain Consortium at the State Health Institute. "They go hand in hand."

But Zadina believes that he is already close to their separation. Just last winter, he and his team published a work in the journal Neuropharmacology, in which he described how they saved the rats from pain without appearing in those five most common side effects associated with opioids, including increased tolerance, impaired motor function, respiratory depression, which is cause the majority of opioid-related deaths. The next step is testing in humans.

This is just one of many attempts to do away with the long-term damage done while saving people from pain. According to the State Institute of Drug Addiction, up to 8% of patients who have been prescribed narcotic painkillers for chronic pain develop addiction. Therefore, it was quite difficult for patients to get opioids such as codeine to reduce pain, says Thomas. This situation began to change in the 1990s. New opioids, for example, Oxycodone (and new advertising campaigns of pharmaceutical companies) came together with the compelling demands of doctors who treat pain and advocates for patients who claimed that many people with chronic pain - and this disease affects about 100 million Americans - are tormented unnecessarily.

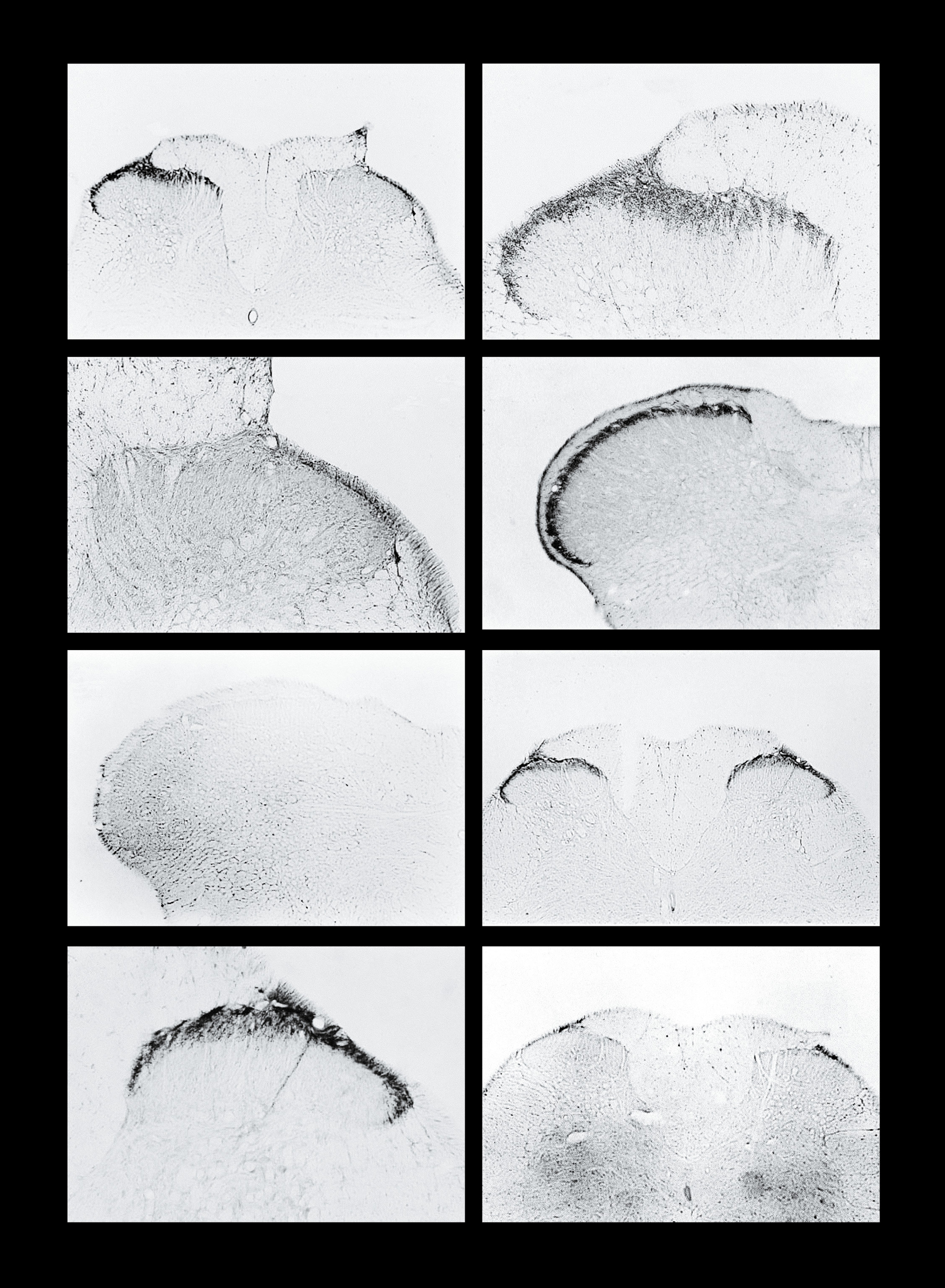

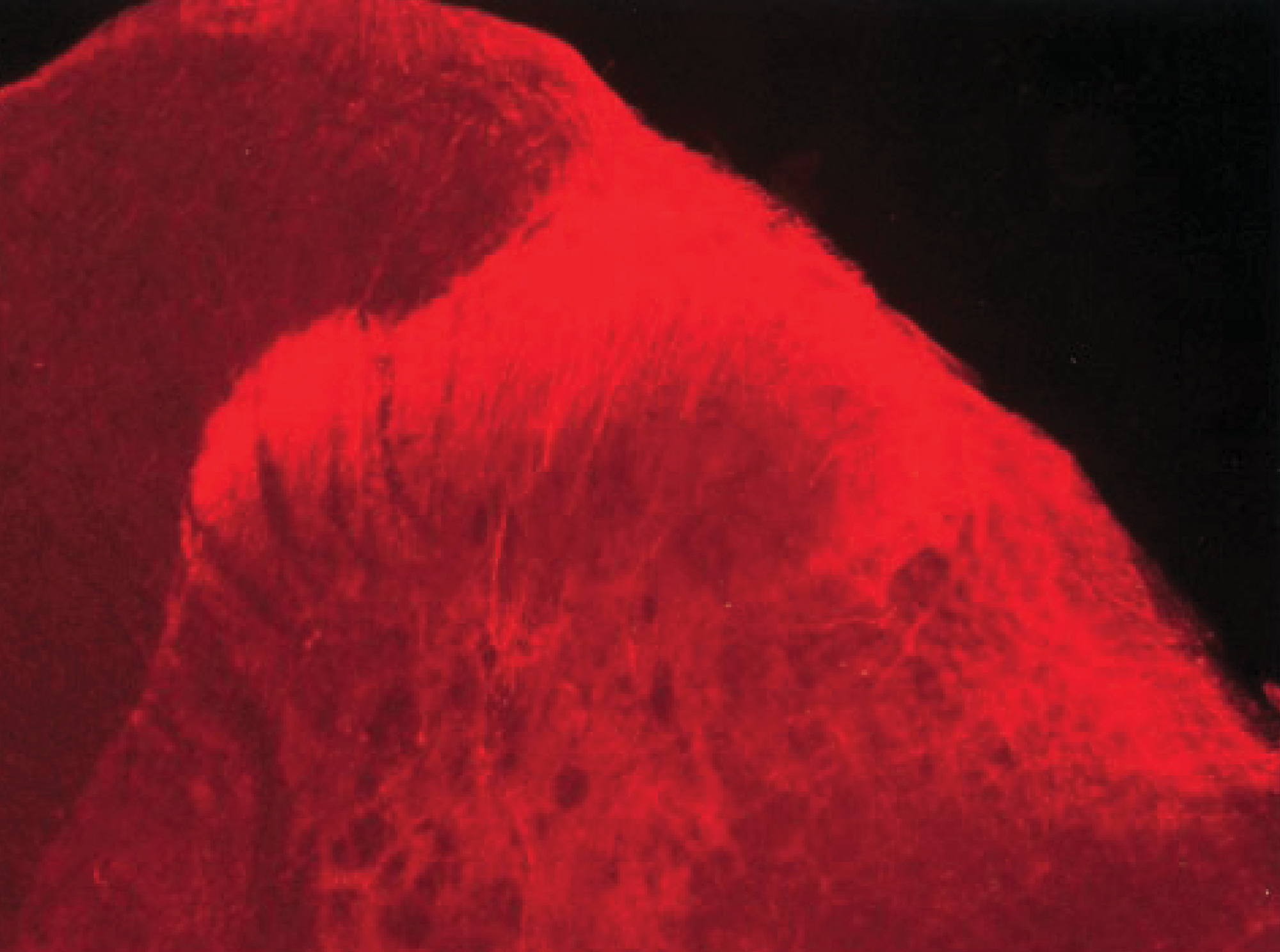

Analgesic substance, endomorphin, reacts with rat spinal cord cells

But the pendulum swung back so far that opioids became the default remedy, even with the best alternatives. Dan Clauw, director of the University of Michigan Research Center for Fatigue and Chronic Pain, says too many doctors tell patients "I was taught that opioids do well with any type of pain and if the pain is too strong and you are already desperate, I I will try this medicine, despite the risk of addiction. "

The consequences were devastating. In 2014, the number of deaths from opioid overdose exceeded 18,000, about 50 people a day — three times more than in 2001. And this statistic does not yet include patients who have switched to heroin to satisfy their cravings. Officials at the Centers for Disease Control compared this problem with the HIV epidemic in the 1980s.

The development of better-quality painkillers faces difficulties as the pain in our body goes along difficult paths. Brain-reaching signals, interpreted as pain, are sometimes caused by problems at the periphery, or on the surface of the body, as in the case of cuts. In other cases, the source of the pain lies deeper: it comes from nerve damage from a serious wound or back injury. Researchers, in particular, Clauw, find evidence that many pain syndromes are caused by the third type of pain: malfunctioning of the brain.

But having such different mechanisms for the occurrence of pain means that there are several different ways to solve the problem of opioids. While Zadina and other scientists are trying to eliminate the dangerous properties of opioids, other painkillers can be aimed at fundamentally different mechanisms of the body.

Stop her

The main way to deal with pain is to reduce the signals sent by the body to the brain.

Almost all of our tissues have so-called. “Nociceptive” nerve endings, tiny fibers that collect information and transmit it to the central nervous system and to the brain for processing. These fibers work as pain sensors. Some nerve endings respond to pressure by sending electrical impulses to the spinal cord, and then we feel pain. Other endings respond to changes in temperature, creating pain signals if we are too cold or too hot. After getting injured, inflammatory cells come to this place and release a dozen different chemicals that cause other cells to fight pathogens, clean up debris and start building new cells. But these same inflammatory cells lead to the fact that the nerve endings at the site of injury send more pain signals. With local injury, for example, when you pulled your ankle or sprained your knee, ice, or anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen, you can drown out pain signals.

But sometimes, after a serious injury, amputation, diabetic nerve damage, nerve fibers or the cells from which they originate, physically change. Some genes can be turned on or off. This changes the number or type of active cellular machinery known as sodium channels — proteins protruding from the cells and regulating their ability to generate electrical impulses. Nerve cells can communicate with each other through these impulses and the sudden activity of additional sodium channels can cause the nerve to give impulses, like a machine gun, "spontaneously, even in the absence of threatening stimuli," explains Stephen Waxman, professor of neurology at Yale University, managing the Center for Neurology and Regeneration Research at the Connecticut Veterans Hospital. These impulses cause people acute pain. One of the common causes is chemotherapy. “Sometimes the pain is so strong that people say,“ I can't stand it, ”says Waxman. "I'd rather die of cancer than experience pain from the treatment."

There are nine types of sodium channels. A painkiller used by dentists is capable of locally blunting it all at once. But this approach does not work in the general case, since some of these channels are present in the brain and the central nervous system. But Waksman is a backbone of researchers looking for ways to influence only one key channel. He discovered its importance by studying people with genetic abnormalities that impede the formation of this channel. Their channel is missing this channel, and they live without feeling pain. Conversely, people born with the hyperactive version of this channel feel “as if their body is in contact with lava,” says Waxman.

The drug, created on the basis of Vaxman's discoveries by Pfizer, was tested on five patients. In addition, similar painkillers are being developed. Theoretically, they should not have serious side effects.

Which brings us back to opioids.

Click switch

Our peripheral nerves, which send us signals of pain, go to the spinal column, where they connect to nerve cells that carry messages to the central nervous system and neurons in the brain, after which we begin to feel pain.

This is where all the opioids, from Oxycodone to heroin and morphine, do their magic. They do this by attaching to mu receptors at the junctions where the nerve cells meet. This causes the switch to click, reducing the ability of these cells to generate signals. And when the nerve fibers in the periphery of the body send pain signals to the brain, the neurons that make us feel pain do not respond.

"Opioids do not affect the source of pain, they only disable brain pain awareness," says Lewis Nelson, an ambulance professor at New York University School of Medicine, who met on the commission that issued recommendations on the use of opioids at the Centers for Disease Control. "A small dose of opioid changes the feeling from being extremely annoying, to one that you don't have to think about."

Mu receptors respond not only to painkillers, but also to "endogenous opioids" - natural signaling compounds produced by our body, such as endorphins, produced during exercise and leading to a "runner high". The problem is that the body does not respond to drugs like heroin or Oxycodone as well as endogenous substances.

Unlike endogenous opioids, pain relievers often activate specific cells in the CNS, known as glia. Glia cleans up cellular debris in the body and helps manage the response to injuries of the central nervous system. After activation, they produce inflammatory substances that can cause the body to register more pain signals. Many researchers believe that an increase in the activation of glial cells can lead to addiction, which is why opioids lose effectiveness over time and the patient needs increased doses to achieve the effect. In the end, these doses can lead to deadly breathing problems.

All this could have been avoided if Zadina could develop a synthetic opioid, more similar to the body's own substances, such as those that act on mu receptors without affecting the glial cells. In the 1990s, he and a team isolated a previously unknown neurochemical compound in the brain, a substance that reduces pain, which was called endomorphine. Since then, he has been trying to create his improved synthetic version.

And one of the versions was a medicine, tested Back on rats, which was described in a paper published last winter in the journal Neuropharmacology. As in the case of other compounds developed by him, this version proved to be no worse, and perhaps better, morphine in ridding animals of pain without the occurrence of side effects. Now he is negotiating with several investors and biotech companies interested in turning this substance into a medicine. When he and his colleagues find enough money to open their company, or sign a contract with a partner under a license, they will ask for approval to conduct early tests on people. “Until you check on people, you will not know,” he says.

The drug of Zadina will still most likely activate the areas of the brain associated with the reward and can lead to a slight euphoria that can incline someone to addiction. But the rapid addiction, usually occurring with opioids - and the withdrawal symptoms that accompany people stopping their medication - are likely to disappear. “I want to eliminate the dilemma faced by doctors and patients,“ Is it possible to eliminate pain completely with the risk of causing addiction, or to eliminate it completely, because I do not want to use opioids? ”Zadina says. “This is my main incentive.”

But even if this new drug is successful, neither he nor the new painkillers working with sodium channels will be able to cope with the new type of pain, the existence of which we didn’t suspect until recently - pain that does not respond to opioids. Clauv from Michigan has been studying this kind of pain for the past 20 years. Based on snapshots of the brain, he determined that it was due to the malfunctioning of the neurons, and not because of a problem in a place that seems to be a source of pain. He believes that this is the most common cause of pain in young people suffering from diseases that confused doctors, including fibromyalgia , certain headaches and irritable bowel syndrome. What should these patients take instead of the often prescribed opioids? Many, according to Klauv, must take medications that eliminate the incorrect activation of neurons by enhancing neurotransmitters. Some drugs that have been developed as antidepressants can achieve this effect.

Image from 1998, showing the presence of endomorphine in the ways in which pain is transmitted to the brain

Thomas from the State Institute of Health believes that the Klauwa study proves that opioids are prescribed too often today.

"If you got into an accident, were hurt in a fight, your arm was torn off, or something like that, and it really hurts you, they will cut off very strong boles very quickly," says Thomas. “But now they are used in many different cases where opioids do not benefit the patient in the long term."

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/396875/

All Articles