History of capacitors part 1: the first discoveries

The history of capacitors begins with the first attempts to study electricity. I liken them to the first steps of aviation, when people made planes of wood and fabric and tried to jump up into the air, not understanding aerodynamics enough to figure out how to stay at the top. There was a similar period in the study of electricity. By the time the capacitor opened, our understanding was so primitive that it was thought that electricity was a liquid that existed in two forms — glassy and resinous. And, as you will see later, everything changed in the early years of the development of capacitors.

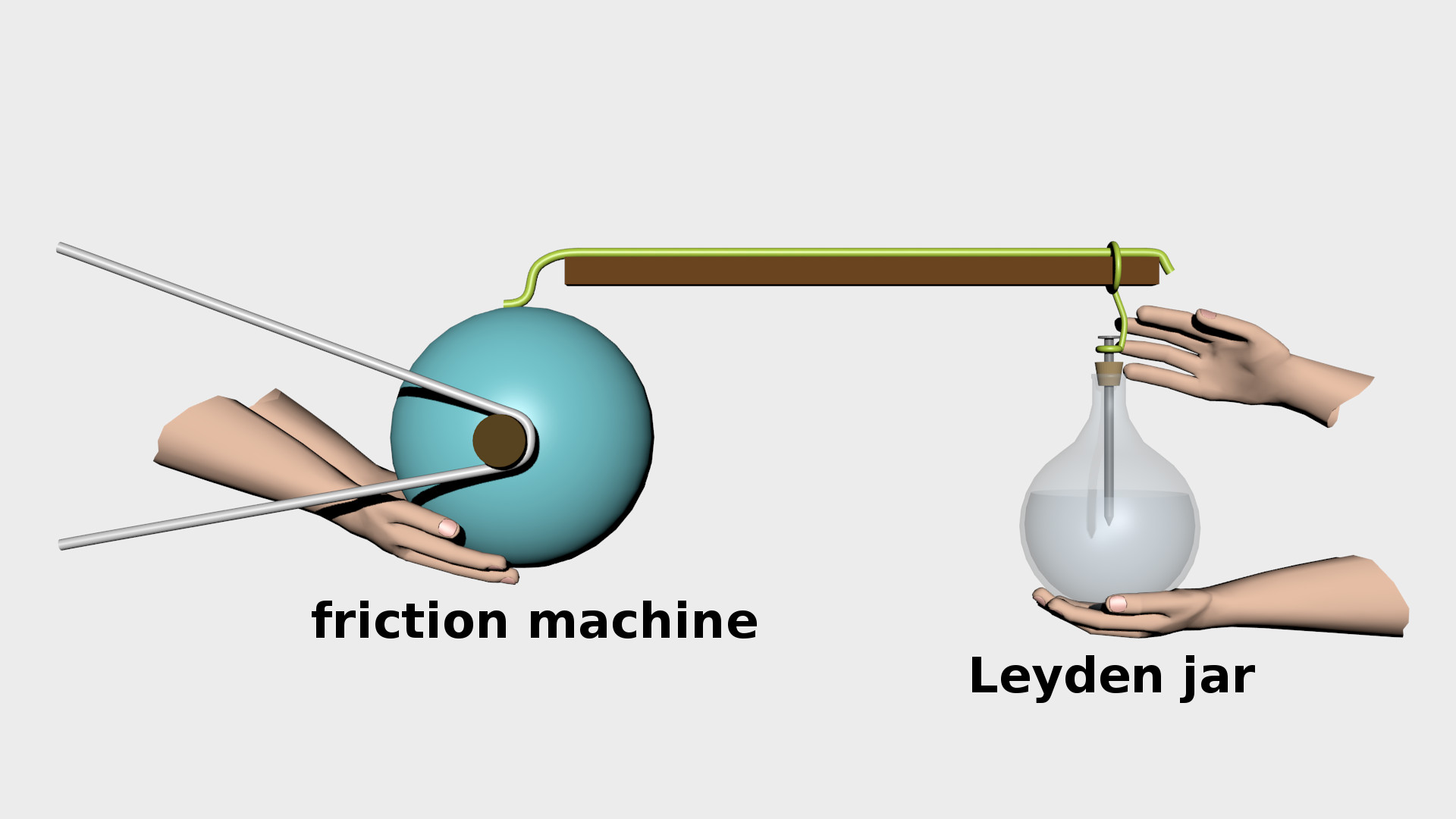

The story begins in 1745. At that time, electricity could only be generated by an electrostatic generator. The glass ball rotated at a speed of several hundred revolutions per minute, and the experimenter touched it with his hands. The electricity accumulated on it could be discharged. Today we call this effect triboelectric - here you can see how it can be used to power an LCD screen.

')

In 1745, Ewald Jurgen von Kleist from Pomerania (Germany) tried to store electricity in alcohol, deciding that he could transfer electricity through a conductor from a generator to a glass medical vessel. Since electricity was considered liquid, this approach seemed reasonable. He believed that glass would prevent electric fluid from escaping from alcohol. He did it in much the same way as shown in the picture, passing the nail through the cork and lowering it into alcohol, holding the glass bottle with one hand. At that moment he did not guess the important role of the hand. Von Kleist discovered that he could get a spark if he touched a wire that was more powerful than if he used only one generator.

He announced his discovery to a group of German scientists at the end of 1745, and the news reached the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, but was misplaced along the way. In 1746, Peter van Mushenbruk and his student Andreas Kuneus successfully repeated the experiment, only with water. Mushenbruck informed the wider French scientific community about the results of the experiment. It is believed that Mushenbrook made this discovery independently. But this was only the beginning.

Jean-Antoine Nolé (also known as Abbot Nolé), a French experimenter, dubbed the vessel Leiden and sold it as a special kind of bottles to rich people interested in science.

It was at Leiden University that they found that the experiment only works if you hold the container with your hand and not support it with insulating material.

Today we understand that the liquid in contact with the glass worked like one plate of a capacitor, and the hand like the other, the glass was a dielectric. The high voltage source was the generator, and the arm and body provided the ground connection.

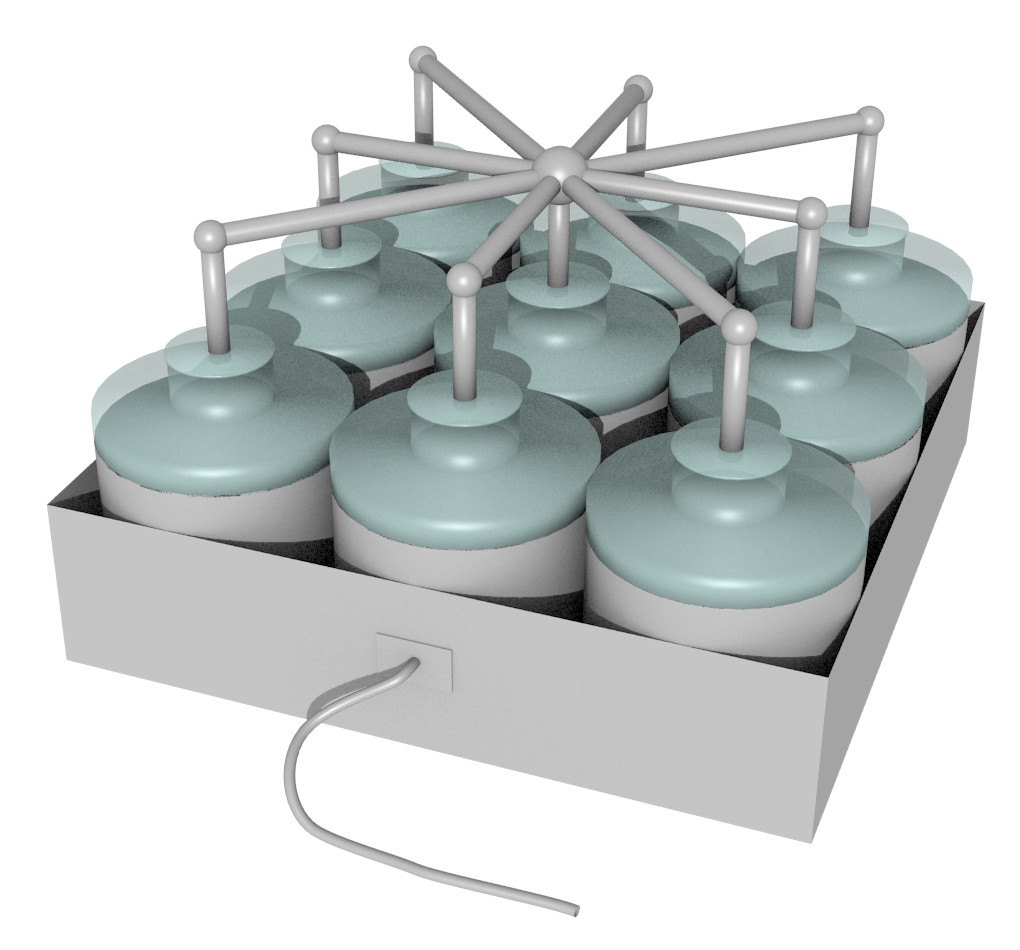

Daniel Gralat, a physicist and mayor of Gdansk (Poland), was the first to unite several vessels in parallel, thereby increasing the amount of stored charge. In the 1740s and 1750s, Benjamin Franklin also experimented with leyden banks in a territory that soon turned into the United States of America and called the collection of several cans a battery, because of its similarity to a battery of guns.

Leyden battery

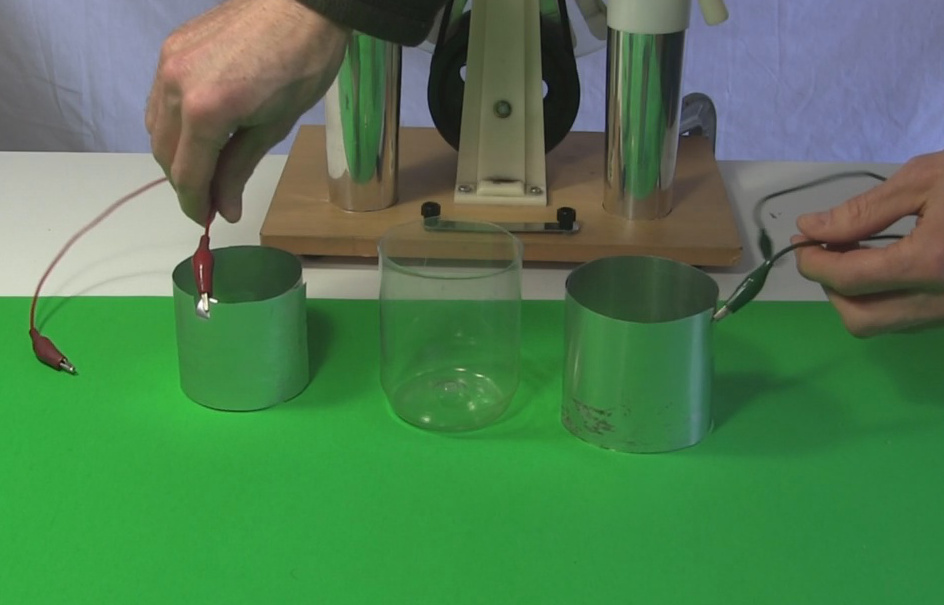

parse the can

disassembled bank

Franklin experimented with bottled water and with the foil that washed the bottles, and decided that the charge was stored in glass, not in water. He worked with collapsible Leyden jars, in which the outer and inner foil was removed from the glass. It was later proved that he was wrong. Franklin worked with absorbent glass, and when he removed the foil, the charge moved through the corona discharge into moisture in the glass. If you use a container made of hard paraffin or tempered glass, the charge remains on the metal plates. There is another effect, dielectric absorption , due to dipoles in a dielectric, in which the capacitor retains charge even after shorting the plates.

Franklin worked with flat glass plates, with foil on both sides, describing the construction of several such capacitors in one of the letters.

Around the same time, other experiments of Franklin showed that only one substance is responsible for charge transfer, although it was still considered liquid - the discovery of an electron was to happen only around 1800. He found that in a charged object there is either an excess of this “liquid” or a deficiency. This disproved the hypothesis of two types of electricity.

In 1776, Alessandro Volta, working with various methods for measuring electric potential, or voltage (V) and charge (Q), discovered that for a given object, V and Q are proportional, calling it “the law of capacitance”. Thanks to this study, the voltage unit was named after him.

The term “capacitor” was not used until the 1920s. For a long time they were called condensers, and they are still called so in some countries and for some purposes [for example, in our country, in English they are called “capacitor” from the word “capacity” - “capacity” / approx. trans.]. The term condenser was proposed by Volta in 1782, and was derived from the Italian condensatore. The name meant the ability of the device to store a higher charge density than an insulated conductor.

Faraday Apparatus

In the 1830s, Michael Faraday conducted experiments that determined that the material between the plates of a capacitor affects the amount of charge remaining on the plates. He experimented with spherical condensers - two concentric metal spheres, between which could be air, glass, wax, shellac (resin) or other materials. Using Coulomb torsion scales , he measured the charge of a capacitor when there was air between the spheres. Then, keeping the voltage unchanged, he measured the charge, filling the gap with other materials. He found that the charge was greater if other materials were used instead of air. He called it a special inductive capacity, and because of this his work, the capacity units are called farads.

The term "dielectric" was first used in a letter from William Uivela to Faraday, where he described how Faraday coined the term "dimagnet" by analogy with "dielectric", and that probably would have to use the term "diamagnetic", but then it would be inconvenient use the term "dielectric" because of three vowels in a row.

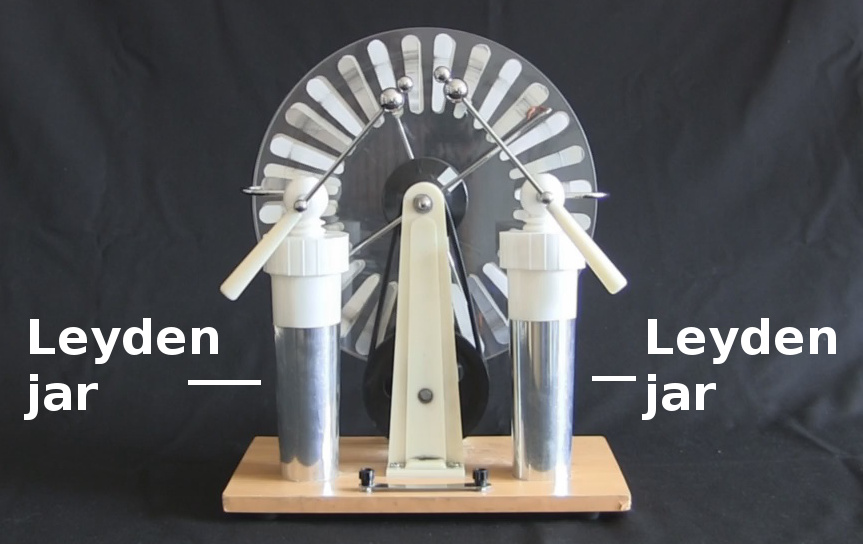

Wimshurst generator

Leyden jars and capacitors made of flat glass and foil were used for spark transmitters and medical electrotherapy until the end of the 18th century. With the invention of radio capacitors began to gradually take the modern form, mainly because of the need to reduce the inductance, to work at high frequencies. Small capacitors were made of flexible dielectric sheets, such as oiled paper, often curled, with foil on both sides. The history of modern capacitors is described in a separate post.

Interestingly, the early capacitors are very similar to homemade, and some were really made by enthusiasts. Leyden banks are now used by high-voltage amateurs, as in this Weimsherst generator, printed on a 3D printer , and as in this entertainment with a " death can ."

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/396509/

All Articles