Why string theory is not a scientific theory

Scientists are working on it, it is coordinated with science, and hopes are expressed that it can be the greatest scientific breakthrough. But it lacks the key ingredient.

Now string theorists have no explanation for why there are three large spatial dimensions and time, and the other dimensions are microscopic. Assumptions on this subject are made very different.

- Edward Whitten

')

There are many ways to define science, but one of those with which everyone can agree, perhaps, describes science as a process, as a result of which:

knowledge is gathered about natural processes or a particular phenomenon;

a verifiable hypothesis is put forward, containing a natural, physical explanation of this phenomenon;

this hypothesis is tested and either confirmed or refuted;

a more general framework, or scientific theory, is constructed, describing a hypothesis and making predictions of other phenomena;

it, in turn, is also checked and either confirmed, in which case the search for new phenomena begins, which can be checked (back to the 3rd step), or refuted, in which case a new tested hypothesis is put forward (back to the 2nd step).

And so on. This scientific process always includes the constant collection of new data, the refinement or replacement of hypotheses when the process is beyond the scope of the hypothesis, and the verification of the theory with the aim of its confirmation or refutation.

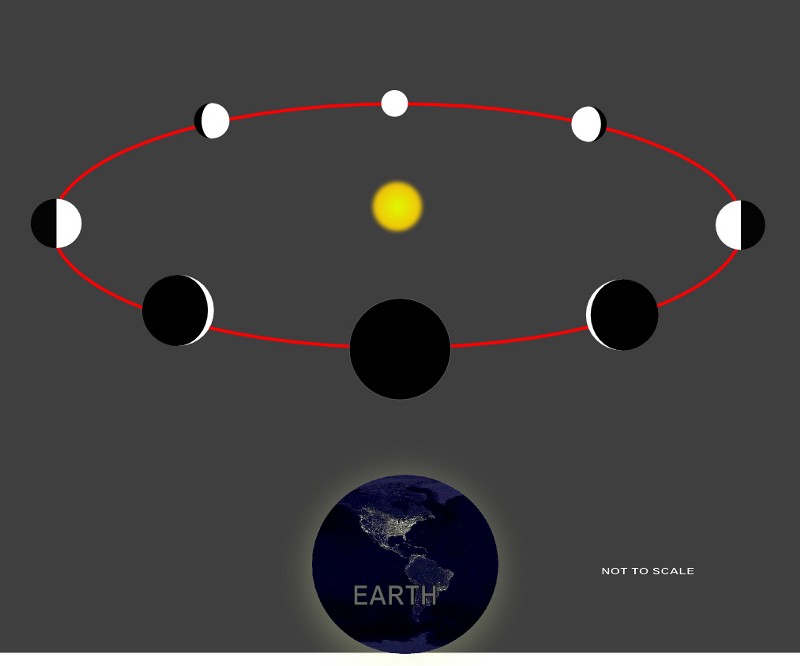

This is how science has always advanced, whether we admit it or not. Heliocentrism replaced geocentrism because it explained phenomena that geocentrism could not explain, including:

- the moons of Jupiter;

- the phases and relative sizes of Venus and Mars at different times of the year;

- frequency of cometary orbits.

Newtonian gravity replaced the Kepler laws because of its ability to make predictions, combining ground and celestial mechanics. Even Einstein's theory of relativity, general and special, appeared in response to the impossibility of Newtonian mechanics to explain behavior at speeds close to the speed of light, as well as in strong gravitational fields. To do this, it was necessary to conduct observations that were impossible during Newton's time, for example, to measure the lifetime of particles appearing during radioactive decay and the orbit of Mercury around the Sun over the centuries. Continuing data collection — in new conditions, with increased accuracy and over longer intervals — enabled us to see flaws in bright, but short-lived scientific theories, and also to see the potential for expansion beyond them.

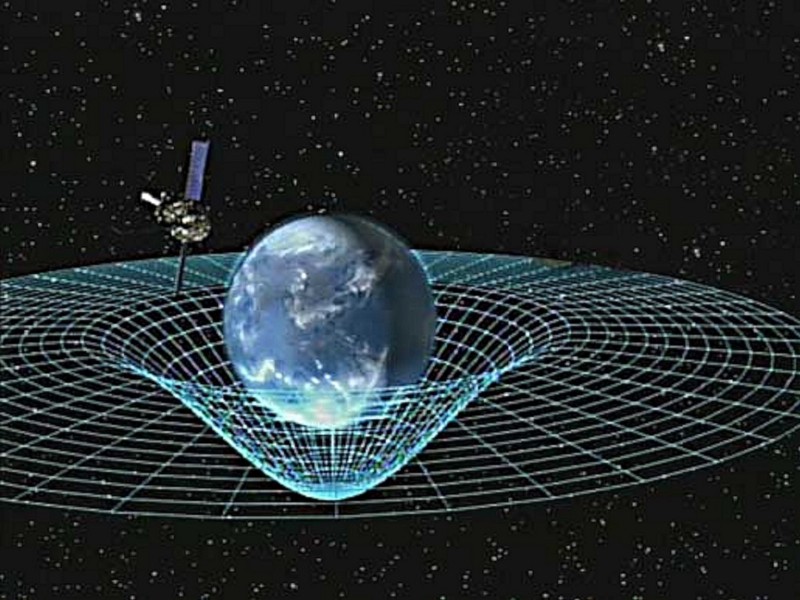

Fast forward to today. Einstein's GTR remains the leading theory of gravity, she passed all the experiments and observations she underwent, from gravitational lensing to entrainment of inertial reference systems and reducing the orbits of double pulsars, and the three remaining fundamental interactions — electromagnetism, weak and strong — are described by quantum field theories. These two classes of theories are incompatible and incomplete, which shows that there are many things in the Universe that we do not understand, despite the success of the Standard Model and the need for the quantum theory of gravity.

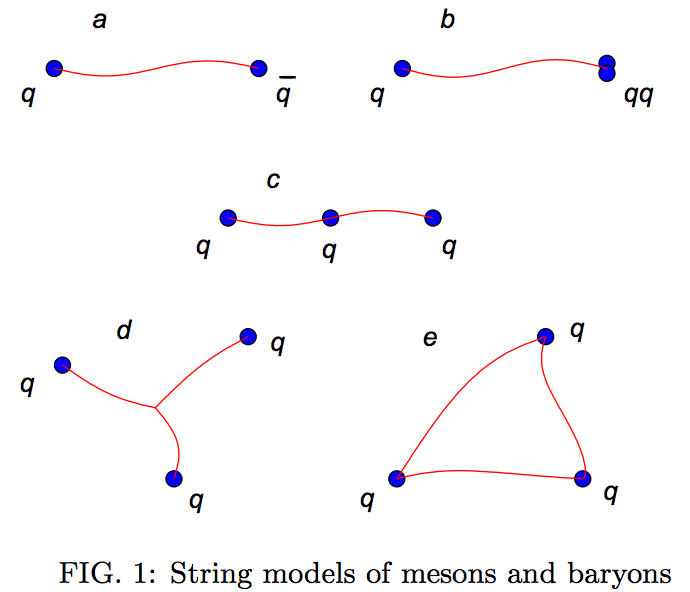

One solution to this puzzle is string theory, the idea that everything that we perceive as particles or interactions is only a manifestation of open or closed strings vibrating at certain unique frequencies.

It may seem that since we call the idea of string theory and offer it as a possible solution to a scientific problem, we have already answered the question in the affirmative: yes, string theory is scientific. But it can be called a theory only in a mathematical sense, that it has its own set of axioms, postulates, elements, theorems and conclusions that can be drawn from this. Set theory, group theory and number theory are examples of mathematical theories, and string theory is another similar example.

But is this a physical theory?

She makes physical predictions, for example:

- the existence of ten dimensions;

- about the predetermination of the fundamental constants "vacuum";

- the existence of supersymmetric particles;

- about the existence of mathematical equivalence between the theory of quantum gravity in, say, five-dimensional space and field theory without gravity on the boundary of this space (four-dimensional).

This, of course, predictions about the physics of the universe. But can they be checked?

So far the answer is no. The first problem is extremely serious: you need to get rid of six dimensions in order to arrive at a perceived Universe, and this can be done in so many ways that their number is greater than the atoms in the Universe. Even worse, each of them gives its own version of the “vacuum” in string theory, without an understandable way of obtaining the fundamental constants describing our Universe - and this is the second prediction.

The third has not yet been confirmed, but we will need energy ~ 10 15 times greater than what the LHC gives to completely eliminate string theory and disprove it. In addition, supersymmetric particles are not a unique prediction of string theory. Their discovery will only mean that the string theory is not excluded, and not that it is correct. And the last prediction is mathematical, not physical. It does not give us the opportunity to observe or test something.

And although recently there was an entire conference on it, the impetus for which was controversial work written last year by George Ellis and Joe Silk, the answer is clear: no, string theory is not scientific. People are trying to turn it into a science — as Sabrina Hossenfelder and David Castelvecci [Sabine Hossenfelder and Davide Castelvecchi] said — by changing the definition of science.

This is such nonsense! If I show you a tulip and say, “This is a rose,” you can show me all the roses in the world and say, “No, these are roses, and you have a tulip.” And if I change the definition of a rose so that it includes tulips, will it become a rose because of it? Or will I just turn a useful definition and separation into a less useful one?

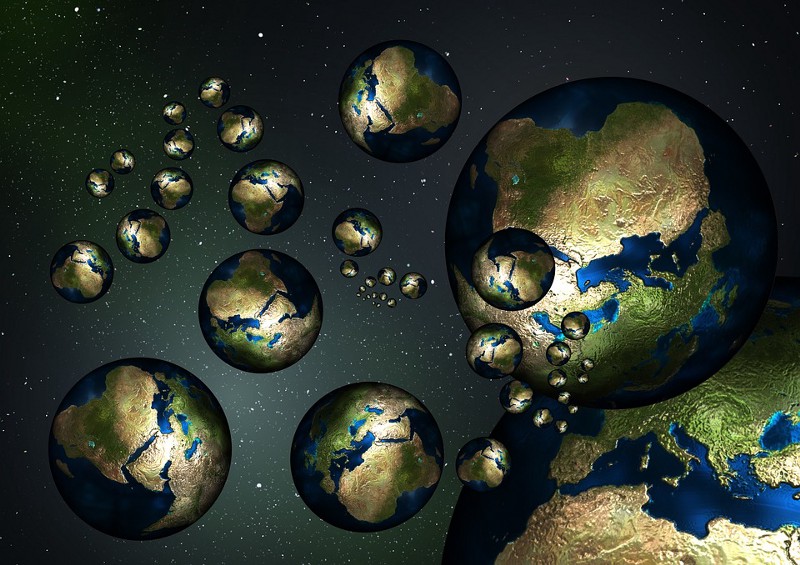

To rise to the level of a scientific theory, you need to make a verifiable — and therefore refutable — prediction. Even a physical state arising from an established theory, such as multiple universes, will not be a scientific theory until we find a way to confirm or deny it; it is only a hypothesis, even if it is a good hypothesis. Interestingly, when the string theory was proposed for the first time, it was called the string hypothesis, since everyone understood that it had not yet risen to the level of an adult theory. (Of course, at that time she postulated that the strings were fundamental entities inside atomic nuclei instead of quarks and gluons).

And this is still a physical hypothesis, and perhaps someday it will become a physically interesting scientific theory. On this day, we are all proud to welcome the string theory, which is part of the scientific community. Until then, we agree that the string theory is interesting, thanks to the possibilities contained in it. Whether these possibilities have meaning and meaning for our Universe - today's science cannot answer this question.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/396263/

All Articles