Turn over Armstrong or the story of the first moon walk broadcast

When 530 million people clung to their television screens to see the first man landing on the moon, except for the heroes of the day Armstrong and Aldrin were still dozens and hundreds of unnoticed Atlanteans who kept a live TV broadcast on their shoulders. And if some showed the highest professionalism, others made silly and now funny-looking mistakes. Because of one such mistake, for example, the first thirty seconds the image was upside down. Even a small immersion in the history of the first live broadcast from the surface of the moon gives us a collection of amazing stories.

Little materiel

On the Apollo 11 landing module, there was a slow-scan television camera that captures an image of 320 lines high and 10 frames per second.

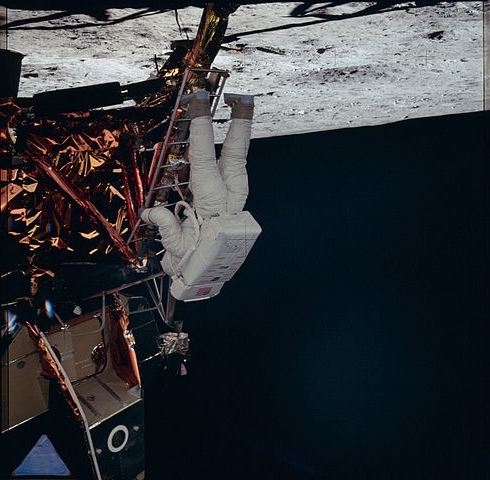

Important note: the camera was attached upside down, simply because its top was the only flat surface. On the opposite side, there is a handle that can be held in your hands or mounted on a tripod. With the pen down, it will already show the correct, not inverted image.

')

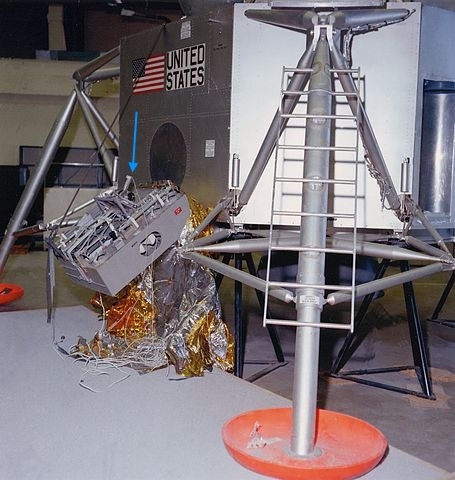

The camera was to the left of the hatch and the stairs on one of the legs of the lunar module (photo from the simulator):

The signal from the camera through the S-band antenna went directly (without retransmission through the command module) to Earth.

On Earth, it was received by four stations - Goldstone in California with an antenna diameter of 64 meters, Parks near the town of the same name in Australia with the same antenna, Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station near Canberra in Australia with an antenna diameter of 24 meters and Madrid in Spain with 34 meter antenna.

Parkes Station

At the time of the start of the astronauts coming to the surface of the moon, Madrid was on the other side of the earth, Goldstone was preparing to finish the work, and Parks with Honeycake Creek were about to start work.

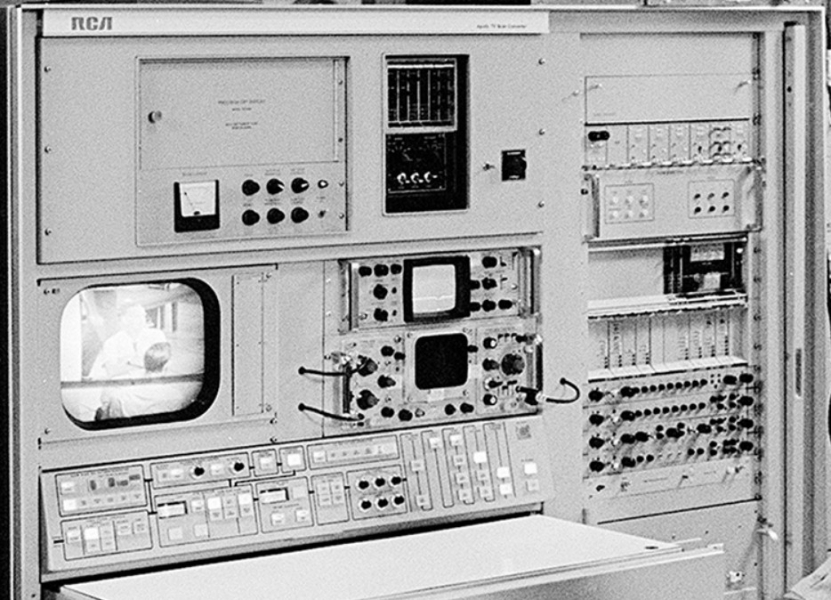

The received ground antenna signal was fed to a special device - a scan converter. The signal was displayed on a kinescope, which was shot by another NTSC camera with a standard resolution of 525 lines and 30 frames per second. Then the signal went through Houston to the television companies.

Scan converter

The first story. They fly - we repair

A few weeks before the Apollo 11 flight, the Parks station scan converter exploded. The reason was offensively simple. Scan converter American production required a three-phase current. According to American standards, black wire marked the phase, and green - the ground. But the Parks Observatory is located in Australia, where the black color of the wire is neutral. Despite the fact that the device was assembled correctly and had time to conduct several trainings, one fine evening one of the technicians rearranged the wires to the Australian manner and the next time the current was turned on, it was not at all where it was supposed to be. A lot of equipment burned down, the replacement of which had to be urgently purchased in Sydney. In addition to cameras, monitors and recorders, all the logic circuits burned, and the technicians had to rewire more than a hundred burnt transistors when the Apollo 11 was already on its way to the Moon. But people managed.

From left to right: Ted Knotts, Richard Hall (head) and Elmer Fredd against the background of a scan converter

The second story. Through the storm

The next problem was literally visible from the moon. Under the law of meanness, the weather was fine all the days of the flight, but on the day of the landing a cyclone appeared, approaching Australia.

The only photo from that day

Antenna Parks had a large sail, and it was forbidden to use in a strong wind. Worse, the moon was low above the horizon, and the antenna dish was supposed to turn to the maximum vertical position with the greatest sail. The wind gusts at 110 km / h beat it twice, knocking the antenna tuning, threatening to break the gears of the drives or, in the worst case, tear the antenna off the mounts. Under the sound of a warning signal, the staff checked the stretch sensors in the walls - whether the tower collapses under the antenna. Working in conditions of a tenfold excess of the design wind load, the staff retorted the antenna jerks from the wind and kept it manually directed to the Apollo 11 landing area. The antenna operator, Fox Mason, could not tear himself away for a second and could only see the exit to the surface of the moon in the evening, in repetition.

Fox mason

The third story. Broadcast

When the TV signal fuse was turned on at the Apollo 11, the original signal was turned on from the Goldstone station. And he was upside down! The staff simply forgot that the camera on the lunar module is lying upside down, and they need to turn on a special inverter. For thirty seconds, operators in Houston waited for Goldstone to switch one toggle switch, but without waiting for it, they turned the image around.

In addition to this problem, the signal from Goldstone was too contrasting. As it turned out later, there could be two reasons for this. Shortly before the Apollo 11 flight, Goldstone stations installed filters to improve the signal. But their bandwidth was about two times lower than the signal from the moon, which reduced the dynamic range of the image and made it black and white without halftones. The second version is incorrect setting of the black level in the scan converter. As a result, when the operators in Houston switched to HoneyCleak Creek with a 24-meter antenna, the image was better than on the 64-meter Goldstone antenna.

Four minutes later, an operator in Houston switches the picture from Honey Creek back to Goldstone, hoping that they have fixed their problems. But in Goldstone they switched the wrong toggle switch, and instead of flipping, the images show inverted colors with black instead of white! We have to go back to Honey Creek.

And what about Parks with a gorgeous 64-meter antenna? But he still can not turn around - the moon is too low. But the antenna has an offset feed when the less powerful receiver is out of focus of the antenna.

Fox Mason extremely professionally holds the antenna so that the offset receiver rises and the main receiver is at the lowest level in order to pick up the signal as quickly as possible:

But the signal is still bad. The picture from the offset receiver jumps, then appearing, then disappearing. Finally, the moon rises high enough, and Parks moves to the main receiver. But operators in Houston are in no hurry to switch! Richard Hall even had to start swearing with an operator choosing a signal so that Parks would be noticed. Only in the ninth minute Houston finally switched to the best signal.

Here is a video that went on the TV viewers, obviously, on the channel CBS.

On it you can see:

2:26 - Start of the inverted broadcast.

2:54 - The image is turned back.

4:06 - Image brightens, switched to Honey Creek.

7:17 - Switch to a negative image of Goldstone.

11:30 - Image enhancement, Parks finally turned on.

Relatively recently, the image was restored, and in the improved version there are no these artifacts.

But, alas, this restoration is worse than it could be. Remember the story of “lost NASA tapes”? Magnetic films of an initial signal in a format of television with slow scanning were meant. These films were not put in a separate special storage, and, most likely, they were overwritten with some new data. And in vain. Those who photographed the screens on which the original signal was sent, clearly saw that the scan converter made the image much worse.

However, this sadness is not so great. In addition to the camera on the lunar module, there was another 16-mm camera that shot the same events in color with much better quality. And you can look at the same events from two or even three (+ astronaut cameras) points.

And about the events in Parks there is a wonderful film “The Dish” .

The main source is “On eagle's wings. The Parkes Observatory's Support for the Apollo 11 Mission

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/396189/

All Articles