Other chess

but because these things are not in the circle of our concepts.

Kozma Prutkov " Thoughts and Aphorisms "

Over the centuries of its development, chess gave us a lot of games. Chaturanga and Shatranj , Makruk and Sittuyin - it seems they have no number! Some of them, such as the Buryat Shatar , differ very little from the usual Chess , others have gone so far in their changes that it would seem that they have nothing in common with them. Today, I want to talk about the Korean chess tradition.

Starting a conversation about "Korean chess" will have, oddly enough, with China. It is officially believed that the modern version of Xiangqi was standardized by the emperor Wu Di from the Zhou dynasty in 569 AD, but the games “on the board with figures” were also played in China earlier. The most ancient game, with a preserved description of the rules, is considered to be a rather curious “ Xiangqi of the seven kingdoms ”, described by the adviser of the Song dynasty, named Sima Qian, who lived in 1019-1086 AD. Presumably, this game was distributed in the period of the "warring kingdoms" from 476 BC, up to the unification of China in 221 BC. It is known that there were more ancient "chess" games (such as " Big Bo " and " Little Bo "), but the descriptions of their rules have not survived to this day.

')

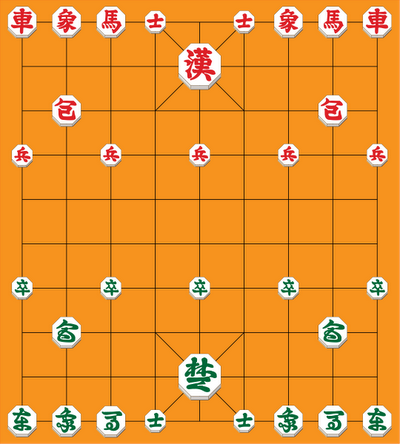

The board for Xiangqi is very different from the familiar chess board. The figures are placed at the intersection of orthogonal lines, and not in the cells of the board, as is common in other chess games. The board is divided into two parts by the “river”, which only certain types of figures can cross. “Palaces”, marked by intersecting diagonal lines, are striking. Generals (an analogue of chess kings), moving one step vertically or horizontally, and their advisers, who are able to move one step along diagonals, cannot leave the palace limits. This greatly simplifies the task of mating , since the general does not have to run all over the board. In addition, while generals cannot leave their “palace,” they can influence each other. Two generals cannot be on the same vertical if there are no figures between them.

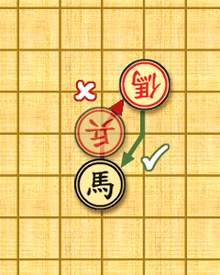

The arrangement of the figures on the first line, in general, resembles the western. On both sides, the palace is surrounded by "elephants", followed by "horses" and "carts." If the moves of the “wagons” are completely analogous to the rules for moving the chess “ rook, ” then there are important differences in the rules for moving other figures. The rules for moving a “horse” are similar to Western ones, but in Xiangqi the “horse” cannot “jump over” other figures (his own or the opponent's). This rule leads to interesting tactical situations, like the following:

The black “knight” cannot attack the enemy, since his movement is blocked by the enemy pawn, but can be eaten by the “red ones”, since the way ahead of their “knight” is free. The "jumping" figure in Xiangqi is the "elephant". It moves exactly two cells diagonally and cannot cross the “river”. However, even beyond the "river" these figures would not have been able to meet with the "elephants" of the enemy. Obviously, "elephants" are very weak figures, but when used properly (especially in pairs), they are very useful for protecting key points of their territory.

Just as the Japanese " Shogi " gave the world the principle of "dumping" of figures, "Chinese chess" gave us a "gun". These are completely unique pieces, two points ahead of the horses in the initial position. The quiet “cannon” move, in Xiangqi, is similar to the movement of a “wagon”, but for the “battle” of an enemy figure, it needs to “jump over” one more figure, its own or its opponent. This figure is called "screen" or "mafia". The guns are very dangerous at the beginning of the game, but towards the end, their value drops as the pieces on the board become smaller and it’s not easy to find the "carriage" to carry out the battle.

It remains to talk about the "pawns". There are fewer of them than in European chess and they cannot “support” each other by “fighting” diagonally. Pawns move just one point. Before crossing the "river" (that is, exactly one move), the "pawns" go only forward, but behind the "river", in the enemy's camp, they get the right to go sideways, left or right horizontally. Unlike Western chess, it does not make sense to rush to the last line with pawns. In "Chinese chess" pawns do not turn into anything (the one who was born a peasant - a peasant will end his life). Having reached the farthest level, pawns can only move sideways. However, this will not prevent them from entering the “palace” of the enemy in order to support the matt attack on the last line.

Xiangqi is very popular not only in China, but also beyond. In Vietnam, this game is widely known as Sò tuóng. In other countries, "Chinese chess" is less popular, but since the Chinese are spread all over the world, Xiangqi, perhaps, can be considered the most massive chess game. They play a very similar game in Korea, but the Koreans would not be Koreans if they had not made their own, very significant, changes to the game.

First of all, you will notice that the general, now, is located in the middle of his palace. In addition, in Janggi (this is the name of this version of the game), players are allowed to change the initial alignment of horses and elephants on their side of the board (which, to some extent, makes this game similar to Fisher's Chess and Sittwein ). In total, perhaps 16 options for the initial arrangement of the figures. The main requirement is the presence of a horse and an elephant on each flank.

There are also significant differences in the rules for moving figures. First of all, in Janggi, both the “general” and his “advisers” can move along all the marked lines inside the palace. Also, along the diagonal lines of the palace, "chariots" and "cannons" can be moved (provided that they entered the enemy palace). Of course, they are still obliged to move in a straight line, in compliance with all the rules for executing their turn. On the diagonal lines of the palace (but only forward), pawns who have entered the enemy's palace have the right to move. By the way, pawns, in Janggi, from the very beginning, on their own territory, already have the opportunity to move one point to the left or right, as well as the Xiangqi pawns who have entered the enemy’s camp. The elephant in Janggi goes in a completely new way:

As well as the "horse", it is not a "jumping" figure. Both cells, through which the "elephant" passes, must be empty. Elephants in Janggi can “walk” across the entire board (you can see that there is no “river” on the Korean board). The greatest changes have undergone "gun". In Janggi, for any of its moves (including the quiet one), the presence of a “mast” (one’s own or an enemy figure) is required. At the same time, the other gun can not serve as a "gun carriage". Also, the “gun” cannot be attacked by another “gun” (which allows you to effectively defend against attacks by guns).

Janggi, in Korea, is taken a little less seriously than Xiangqi in China. Janggi are considered the game of the common people. The intellectual elite of this country prefers Baduk (Korean name of the game is Guo ). Nevertheless, the game is popularly loved and has a rich history. One of the manifestations of such love can be considered the invention of various variants of the game according to changed rules. Most of all, in this respect, the Japanese distinguished themselves. There is simply an incredible number of options for the game Shogi , invented by them (not all here), but the Koreans also invented something .

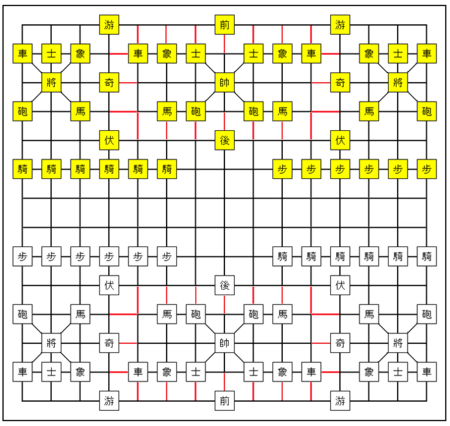

Here Gwangsanghui somehow immediately interested me. Still would! The game of the 18th century, in which there are as many as three "palaces" on each side! It remained to figure out how to go figure. Difficulties immediately arose with this. In principle, the required information existed, but it was in Korean . Google translate helped a little. Fortunately, a good Korean woman (by the name of Jooyoung Lee) was found in Innopolis, who translated this wonderful text to me in English.

Translation text

There are 15 vertical lines and 14 horizontal lines on the board. (15 boxes horizontally, 14 boxes vertically) 210 boxes over all.

It is divided into 6 lines, that is, “the whole army (三軍)”. The intersection of the middle vertical lines, which are 45 dots, are called “the center (中)” and . The 9 boxes are located at the very center of Naeyoung are called “Nine Palace (九宮)”. In the Nine Palace, there are diagonal lines that you can use in the middle.

Behind the King, you put sch (scholar). On both side of 士, you put 象. 車 should be placed on the left and right of. N should not be placed (where 士 didn’t take). 馬 should be placed 2 boxes before 象 (which is left and right of).

24 boxes surrounding “내영 (Naeyoung)” is called “외영 (waeyoung)”.

Placed is placed in the very center (that is 2 boxes above the king). 後將 2 (waeyoung) ”(that is 2 boxes below the king).

In “(waeyoung)”, you can put it on, and you伏.

Out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out out again again again

Inter (left army) 3 lines and 3 bottom lines, right (right army). It should be noted that it has been diagonal lines, where it should be.

Behind left of the left and right army, place a 士.

In the outer room, in the left and right army, in the put, and in the inner room, in the next room, in the put. 馬 left inside and 砲 outside.

Rules moving J 象 象 象 象 砲 and and same same same same same same same same same Only can only move forward 1 diagonally. 步 is the same as 卒 · 兵 in Janggi.

游 moves like 馬 in Chinese Janggi. 伏 can move 1 diagonally. 游 cannot be taken on the board. However, it can only be taken by 伏.

奇 can move horizontally or vertically.

You win if you capture, but if you didn't dominant side wins. It is a concept of the ownership changes. However, if you’re right afterwards, you can get all the lost pieces back.

Only can only be captured when exchanging.

From myself I can say that this is really a very interesting game. In addition to the traditional figures of Janggi, several new figures are added, but the essence is not even in them, but in the variety of tactical situations generated by the game. Most of the collisions in the game are asymmetric (we have already analyzed the situation with the “horses” above). For example, in the game there are two types of pawns - traditional and additional, moving and hitting one point diagonally. Initially, the pieces are arranged in such a way that pawns of different types stand opposite each other. The game has a figure (游) moving as a “horse” that cannot beat other figures and only 伏 can be beaten (there is a similar figure (Diplomat) in the Qiguo Xiangqi mentioned above, but there it is completely invulnerable and moves like chess queen ).

As I expected, the most interesting thing is with the additional "palaces". By capturing an enemy general, in one of these palaces, we gain control over all the figures assigned to him, but only on condition that the attacking figure will not be eaten by the next move. To some extent, this is consonant with the "rule of dumping" of the Japanese Shogi, according to which, the taken pieces are not removed from the board forever, but fall into the player's "reserve" and can be used by them afterwards. I think that, like the “discharge rule”, this rule is a metaphor for the conduct of hostilities from the point of view of the inhabitants of ancient Korea. Capturing the lock, we get all the servants in it, but if the attack is repulsed, the “defectors” are returned under the control of their rightful master:

For me, the phrase relating to the 前 and 後 figures was not completely clear. The rules say “can only be captured when exchanging”, while nowhere is it indicated how these figures go. I think they should remain motionless, protecting the extremely important, in strategic terms, central vertical. This is not an absolute defense, since the figures can be taken, but only by “exchange” (that is, with the loss of the attacking figure). In addition, the target behind them can be attacked by a “gun” (砲). By the way, it may seem that the central "guns" of both sides "shoot through" the side lines of the enemy "palace". Of course, this is not so! In "Korean chess", one "gun" can not use the other as a "mast". In addition, you can not start the game with the “gun” move.

The rest was a matter of technique. The game was developed using " Zillions of Games " and uploaded on GitHub . Those interested can be found. The illustration for the KDPV was taken from the article by Dmitry Skiryuk on art related to Xiangqi figures.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/395761/

All Articles