Chester Carlson - inventor of "Xerox"

Chester Carlson (Chester Carlson) was an American physicist who worked as a lawyer and in his spare time engaged in inventions. It was he who presented the world with a copy machine and made the first photocopy in history.

Chester Carlson was born on February 8, 1906 in Seattle (USA). The future inventor had to grow up too early. When he was still a child, the family moved to Mexico hoping to get rich (yielding to the insane idea of "American colonization of lands"). But they did not work. Moreover, Chester's mother fell ill with malaria and the family was on the verge of poverty. After 7 months of Mexican life, the Carlsons returned to the states. Difficult circumstances forced little Chester to work from 8 years. He studied in high school and worked in parallel for 2-3 hours before and after classes.

')

As Chester recalled:

At the age of 10, Carlson created the newspaper “This and That”, which he distributed among friends and acquaintances. His favorite toy was a set of rubber stamps for printing and a toy typewriter, which he received for Christmas 1916. Chester also tried to impose and publish a scientific journal for students. However, he quickly began to become frustrated with traditional copying methods. Then he first thought about how to come up with simpler ways to make copies. But because of the work, Carlson had to leave school for a year in San Bernardino High School.

In 1924, he joined Riverside College (Riverside Junior College) in the Faculty of Physics, alternating work and classes. Carlson's mother died from the disease and they were left alone with her father. In college, Chester had to work three jobs to pay rent for himself and his father. It was there that he met his first wife Elsa von Mallon (Elsa von Mallon) - she was the daughter of the mistress of the house. Now on that building there is a bronze plaque: “In this apartment Chester Carlson conducted the xerographic process for the first time on October 22, 1938”.

After Riverside, Chester transferred to the California Institute of Technology, with tuition fees of $ 260 per year. He graduated from the Faculty of Physics with good grades and received a bachelor's degree in 1930. Looking for a place, Carlson went around 82 companies, but none offered him a job. In 1936, he enrolled in a law school - the New York Law School (New York Law School), which he graduated three years later with a bachelor's degree in law.

Chester's position improved after he got a job as a research engineer in the Bell Telephone Laboratories lab in New York. But due to the Great Depression, he was fired. Then Chester moved to the patent office, where he became the head of the patent department in the company PR Mallory Company (now Duracell) from a simple lawyer assistant.

Even during the work of Bell Laboratories, Carlson wrote over 400 ideas of new inventions in his personal notebooks. Since he worked as a patent attorney assistant, he had to constantly make many copies of various documents and drawings. As a rule, copying in the department took place with the help of typists who reread patent applications in full and using a carbon paper making several copies. There were also other ways, like a rotator and photocopies, but they cost more than a carbon paper and had their limitations.

Working in the patent department, Carlson wanted to create a "copying" machine that could take an existing document and copy it onto a new sheet of paper without any intermediate steps. So the young inventor had the idea to create a “dry” (Greek xeros) photo without the need to show it. Together with the Austrian engineer-physicist Otto Cornei, they began to implement the conceived apparatus. And the first "laboratory" was the usual kitchen of Chester's mother in law.

Carlson’s experiments in building a photocopier included attempts to generate electrical current in the original sheet of paper using light. The scientist used light to "remove" static charge from a uniformly ionized photoconductor. Since the light did not reflect from the black marks on the paper, such areas remained charged on the photoconductor and, therefore, contained fine powder. He carried the powder on a clean sheet of paper, resulting in a duplicate of the original.

Carlson knew the value of patents, so he patented his development in stages. The inventor filed the first preliminary patent application on October 18, 1937. And in the middle of the autumn of 1938, he and Korney presented the first print. The Austrian wrote "10.-22.-38 ASTORIA" in ink on a glass microsample. He prepared a sulfur-coated zinc plate and a darkened room, rubbed the surface of the sulfur with a cotton scarf to apply an electric charge, then put the microscopic preparation on the plate, exposing it to a bright incandescent light. Next, sprinkled with lycopodia powder on the surface of sulfur, the microdrug was taken away, the excess was gently blown off and the image was transferred onto a waxed sheet of paper. Then they heated the paper, softening the wax so that the lycopodium stuck to it, and got the world's first xerographic copy.

Despite joint achievements, Kornei was very pessimistic about electrophotography. As a result, he ceased to cooperate with Carlson and even broke off the agreement, which promised him 10% of future income from the invention and partial ownership. A year later, when Xerox shares were up to par, Carlson sent Korney a present in the form of hundreds of company shares.

In 1942, Chester received a patent for his invention. But to introduce the device into the business turned out to be a very difficult task - companies were wary of the development. And only in 1944, Carlson found use of the invention thanks to Russell W. Dayton, a young engineer at the Battelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio. Chester made a strong impression on the young man, and although the institute did not develop other people's ideas, he was invited to Columbus, where he was offered to improve the technology.

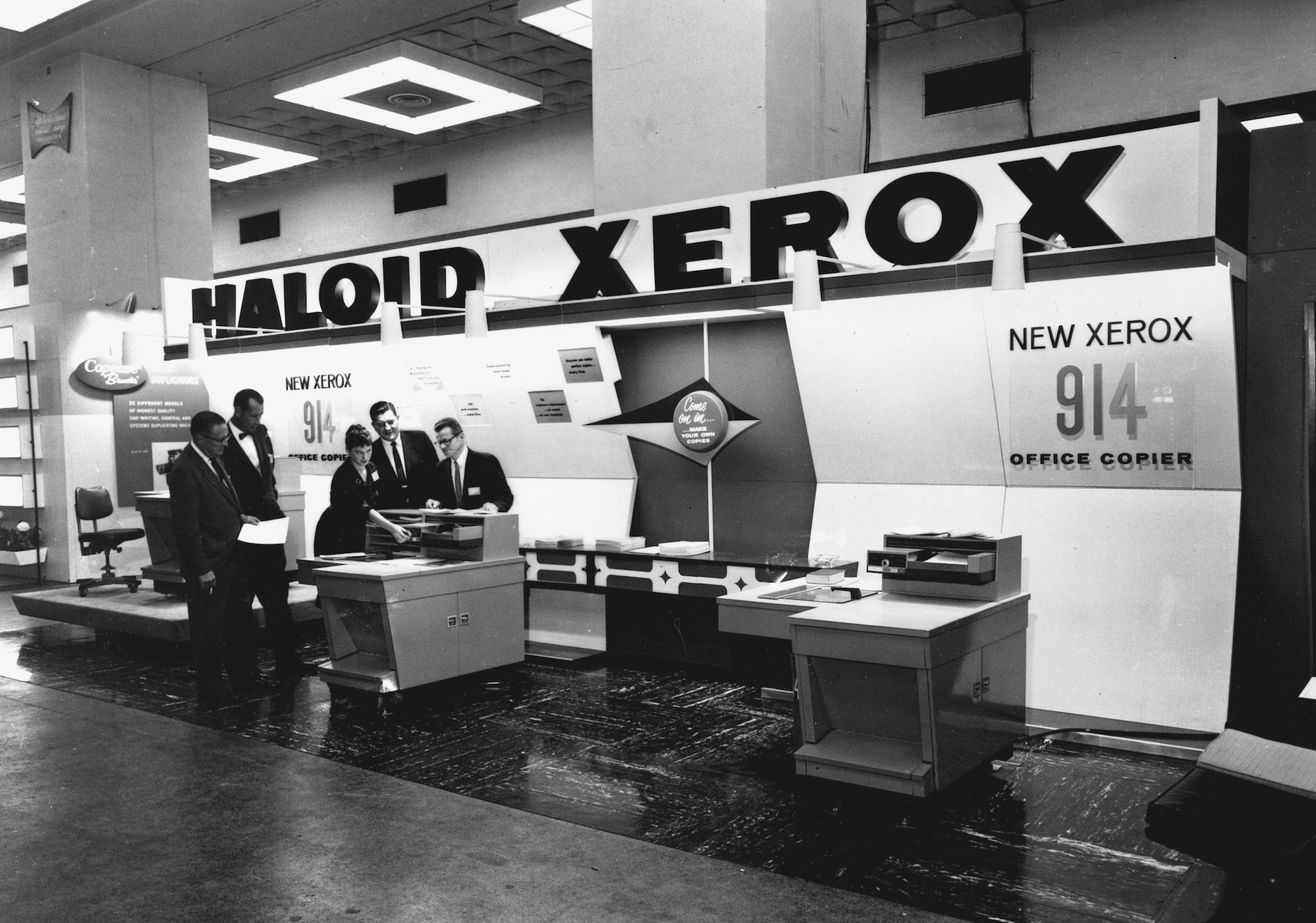

Haloid Company research director John Dessauer (John Dessauer) read an article about Carlson's invention. The company was engaged in the production of photographic paper and tried to get out of the shadow of its neighbor, Eastman Kodak. Electrophotography opened up prospects for Haloid, allowing you to cover a new field of activity. In December 1946, the first agreement on licensing electrophotography for a commercial product was signed between the Battel Institute, Carlson and Haloid.

By 1948, Haloid realized that it was necessary to make a public statement about electrophotography, thereby preserving its patent technology requirements. However, the term "electrophotography" seemed too scientific and difficult for consumers. After reviewing several options, Haloid chose the term “xerography” (other Greek: “dry” and “writing”), coined by a local philology professor at Ohio State University. A little later, Carlson simplify the name to a simple "Xerox".

On October 22, 1948, the Haloid Company made the first public statement on xerography. And in 1949, the company released the first commercial XeroX Model A Copier copying machine, known internally as the Ox Box.

The first copier in the modern sense was the Xerox 914. Despite its cumbersome and rude work, it allowed the operator to place the original on a sheet of glass, press a button and get a copy on plain paper. The Xerox 914 was introduced in 1959 at the Sherry Netherland Hotel (New York) and was a great success.

After the release of the first fully automatic Xerox 914 model, Haloid changed its name to Xerox Corporation. The popularity of the model was due to the relative ease of use, personal design and low maintenance costs compared to other machines that require special paper. But 914 also contributed to the success of the decision to lease the device (at a price of $ 25 per month, plus the cost of copies 4 cents for each copy). Xerox became available, unlike competing copiers.

For Carlson, the commercial success of the Xerox 914 was the culmination of his life. The author’s fee from the Battel Institute was about $ 15,000. He remained a consultant for Xerox Corporation until the end of his life, and from 1956 to 1965 he continued to receive royalties from Xerox, in the amount of approximately one sixteenth cent from each Xerox copy made worldwide .

In 1968, Fortune magazine ranked Carlson among the richest people in America. But this man dedicated his wealth to philanthropic goals. He donated more than $ 150 million to charity and actively supported the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Thanks to his second wife, Doris, he became interested in Hinduism, in particular, in ancient texts known as Vedanta, as well as Zen Buddhism. In their own home, they organized Buddhist meetings with meditation. After reading Philip Kapleau’s book, The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching, Practice, and Enlightenment, Doris invited Kaplo to join their meditation group. In June 1966, they provided funding that enabled Kaplo to open a Zen center in Rochester.

Chester Carlson died on September 19, 1968 of a heart attack at the Theater Festival, where he watched "The One That Controls the Tiger."

The New York City civil rights association was one of the beneficiaries of his will. The University of Virginia received $ 1 million with clear instructions that this money should be used only to finance research on parapsychology. The Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions received under the will of more than $ 4.2 million, in addition to more than $ 4 million, which Chester donated when he was alive.

In 1981, Carlson contributed inventors to the National Hall of Fame.

US law 100-538, approved by Ronald Reagan, appointed October 22, 1988 as the Day of National Recognition of Chester F. Carlson.

Also, the US Postal Service gave tribute to the inventor's fame, including it in a series of postage stamps entitled “Great Americans”.

The buildings in Rochester’s two largest institutions of higher education were named after Carlson: The Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, Department of Visual Information, department of the Rochester Institute of Technology, specializing in remote sensing and xerography; Scientific and Technical Library. Carlson University of Rochester (The University of Rochester’s Carlson Science and Engineering Library).

There are also awards and prizes that bear the name of the inventor.

Childhood and youth

Chester Carlson was born on February 8, 1906 in Seattle (USA). The future inventor had to grow up too early. When he was still a child, the family moved to Mexico hoping to get rich (yielding to the insane idea of "American colonization of lands"). But they did not work. Moreover, Chester's mother fell ill with malaria and the family was on the verge of poverty. After 7 months of Mexican life, the Carlsons returned to the states. Difficult circumstances forced little Chester to work from 8 years. He studied in high school and worked in parallel for 2-3 hours before and after classes.

')

As Chester recalled:

I had to work at an early age in my spare time. But when the opportunity arose, I returned to my own development, creating different things, experimenting and planning the future. I read the works of Thomas Edison and other successful inventors, dreaming of ever becoming the same as they. Inventions attracted by the fact that with their help I could improve my financial situation and improve my economic status. At the same time, I had the opportunity to realize my interest in the development of technical things and make a contribution to the development of society.

At the age of 10, Carlson created the newspaper “This and That”, which he distributed among friends and acquaintances. His favorite toy was a set of rubber stamps for printing and a toy typewriter, which he received for Christmas 1916. Chester also tried to impose and publish a scientific journal for students. However, he quickly began to become frustrated with traditional copying methods. Then he first thought about how to come up with simpler ways to make copies. But because of the work, Carlson had to leave school for a year in San Bernardino High School.

In 1924, he joined Riverside College (Riverside Junior College) in the Faculty of Physics, alternating work and classes. Carlson's mother died from the disease and they were left alone with her father. In college, Chester had to work three jobs to pay rent for himself and his father. It was there that he met his first wife Elsa von Mallon (Elsa von Mallon) - she was the daughter of the mistress of the house. Now on that building there is a bronze plaque: “In this apartment Chester Carlson conducted the xerographic process for the first time on October 22, 1938”.

After Riverside, Chester transferred to the California Institute of Technology, with tuition fees of $ 260 per year. He graduated from the Faculty of Physics with good grades and received a bachelor's degree in 1930. Looking for a place, Carlson went around 82 companies, but none offered him a job. In 1936, he enrolled in a law school - the New York Law School (New York Law School), which he graduated three years later with a bachelor's degree in law.

Career

Chester's position improved after he got a job as a research engineer in the Bell Telephone Laboratories lab in New York. But due to the Great Depression, he was fired. Then Chester moved to the patent office, where he became the head of the patent department in the company PR Mallory Company (now Duracell) from a simple lawyer assistant.

Even during the work of Bell Laboratories, Carlson wrote over 400 ideas of new inventions in his personal notebooks. Since he worked as a patent attorney assistant, he had to constantly make many copies of various documents and drawings. As a rule, copying in the department took place with the help of typists who reread patent applications in full and using a carbon paper making several copies. There were also other ways, like a rotator and photocopies, but they cost more than a carbon paper and had their limitations.

Working in the patent department, Carlson wanted to create a "copying" machine that could take an existing document and copy it onto a new sheet of paper without any intermediate steps. So the young inventor had the idea to create a “dry” (Greek xeros) photo without the need to show it. Together with the Austrian engineer-physicist Otto Cornei, they began to implement the conceived apparatus. And the first "laboratory" was the usual kitchen of Chester's mother in law.

Carlson’s experiments in building a photocopier included attempts to generate electrical current in the original sheet of paper using light. The scientist used light to "remove" static charge from a uniformly ionized photoconductor. Since the light did not reflect from the black marks on the paper, such areas remained charged on the photoconductor and, therefore, contained fine powder. He carried the powder on a clean sheet of paper, resulting in a duplicate of the original.

Carlson knew the value of patents, so he patented his development in stages. The inventor filed the first preliminary patent application on October 18, 1937. And in the middle of the autumn of 1938, he and Korney presented the first print. The Austrian wrote "10.-22.-38 ASTORIA" in ink on a glass microsample. He prepared a sulfur-coated zinc plate and a darkened room, rubbed the surface of the sulfur with a cotton scarf to apply an electric charge, then put the microscopic preparation on the plate, exposing it to a bright incandescent light. Next, sprinkled with lycopodia powder on the surface of sulfur, the microdrug was taken away, the excess was gently blown off and the image was transferred onto a waxed sheet of paper. Then they heated the paper, softening the wax so that the lycopodium stuck to it, and got the world's first xerographic copy.

Despite joint achievements, Kornei was very pessimistic about electrophotography. As a result, he ceased to cooperate with Carlson and even broke off the agreement, which promised him 10% of future income from the invention and partial ownership. A year later, when Xerox shares were up to par, Carlson sent Korney a present in the form of hundreds of company shares.

In 1942, Chester received a patent for his invention. But to introduce the device into the business turned out to be a very difficult task - companies were wary of the development. And only in 1944, Carlson found use of the invention thanks to Russell W. Dayton, a young engineer at the Battelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio. Chester made a strong impression on the young man, and although the institute did not develop other people's ideas, he was invited to Columbus, where he was offered to improve the technology.

Haloid Company research director John Dessauer (John Dessauer) read an article about Carlson's invention. The company was engaged in the production of photographic paper and tried to get out of the shadow of its neighbor, Eastman Kodak. Electrophotography opened up prospects for Haloid, allowing you to cover a new field of activity. In December 1946, the first agreement on licensing electrophotography for a commercial product was signed between the Battel Institute, Carlson and Haloid.

By 1948, Haloid realized that it was necessary to make a public statement about electrophotography, thereby preserving its patent technology requirements. However, the term "electrophotography" seemed too scientific and difficult for consumers. After reviewing several options, Haloid chose the term “xerography” (other Greek: “dry” and “writing”), coined by a local philology professor at Ohio State University. A little later, Carlson simplify the name to a simple "Xerox".

On October 22, 1948, the Haloid Company made the first public statement on xerography. And in 1949, the company released the first commercial XeroX Model A Copier copying machine, known internally as the Ox Box.

The first copier in the modern sense was the Xerox 914. Despite its cumbersome and rude work, it allowed the operator to place the original on a sheet of glass, press a button and get a copy on plain paper. The Xerox 914 was introduced in 1959 at the Sherry Netherland Hotel (New York) and was a great success.

After the release of the first fully automatic Xerox 914 model, Haloid changed its name to Xerox Corporation. The popularity of the model was due to the relative ease of use, personal design and low maintenance costs compared to other machines that require special paper. But 914 also contributed to the success of the decision to lease the device (at a price of $ 25 per month, plus the cost of copies 4 cents for each copy). Xerox became available, unlike competing copiers.

For Carlson, the commercial success of the Xerox 914 was the culmination of his life. The author’s fee from the Battel Institute was about $ 15,000. He remained a consultant for Xerox Corporation until the end of his life, and from 1956 to 1965 he continued to receive royalties from Xerox, in the amount of approximately one sixteenth cent from each Xerox copy made worldwide .

In 1968, Fortune magazine ranked Carlson among the richest people in America. But this man dedicated his wealth to philanthropic goals. He donated more than $ 150 million to charity and actively supported the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Thanks to his second wife, Doris, he became interested in Hinduism, in particular, in ancient texts known as Vedanta, as well as Zen Buddhism. In their own home, they organized Buddhist meetings with meditation. After reading Philip Kapleau’s book, The Three Pillars of Zen: Teaching, Practice, and Enlightenment, Doris invited Kaplo to join their meditation group. In June 1966, they provided funding that enabled Kaplo to open a Zen center in Rochester.

Chester Carlson died on September 19, 1968 of a heart attack at the Theater Festival, where he watched "The One That Controls the Tiger."

Heritage

The New York City civil rights association was one of the beneficiaries of his will. The University of Virginia received $ 1 million with clear instructions that this money should be used only to finance research on parapsychology. The Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions received under the will of more than $ 4.2 million, in addition to more than $ 4 million, which Chester donated when he was alive.

In 1981, Carlson contributed inventors to the National Hall of Fame.

US law 100-538, approved by Ronald Reagan, appointed October 22, 1988 as the Day of National Recognition of Chester F. Carlson.

Also, the US Postal Service gave tribute to the inventor's fame, including it in a series of postage stamps entitled “Great Americans”.

The buildings in Rochester’s two largest institutions of higher education were named after Carlson: The Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, Department of Visual Information, department of the Rochester Institute of Technology, specializing in remote sensing and xerography; Scientific and Technical Library. Carlson University of Rochester (The University of Rochester’s Carlson Science and Engineering Library).

There are also awards and prizes that bear the name of the inventor.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/395325/

All Articles