Secret room 40

In wartime, secure communication channels were used to exchange data. And the interception of transmitted messages with their subsequent decoding - played an important role in the confrontation of states. The brilliant cryptographers of Bletchley Park did a tremendous job and greatly influenced the course of the Second World War. They have gained worldwide fame, forever imprinting their names in the history of cryptography. But the decryption of messages also engaged in the days of the First World War. In Britain, there was a deciphering organization called Room 40 (eng. Room 40), which intercepted and deciphered German messages.

Room 40 was also known as 40 SB. (Old building) and was a division of the leading cryptographic body of Great Britain during the First World War - the British Admiralty. The organization was formed in October 1914, shortly after the start of the war. Room 40 got its name thanks to the room number in the old building of the Admiralty, where it was located. For most of its existence, this organization was a cryptogram analysis and decryption bureau. Its employees decrypted about 15,000 German messages.

')

In 1911, the department of the Defense Committee of the Empire for communication, it was decided - in the event of the outbreak of war with Germany, you must immediately destroy the German underwater communications. On the morning of August 5, 1914, the cable vessel Alert identified and cut off 5 German transatlantic cables that reached the English Channel. Shortly thereafter, the 6 cables that ran between Britain and Germany were also cut off. As a result, increased the flow of messages transmitted by radio. Codes and ciphers were used to hide their content. But to decrypt such messages, neither the UK nor Germany had the relevant organizations. Messages that could be intercepted were sent to the Admiralty intelligence department, which was led by Rear Admiral Henry Oliver since 1913. But there were also no employees who could crack the code. Then Oliver turned to his friend, an engineer with radio communications experience, Sir Alfred Eingu, and asked to form a group to decrypt messages.

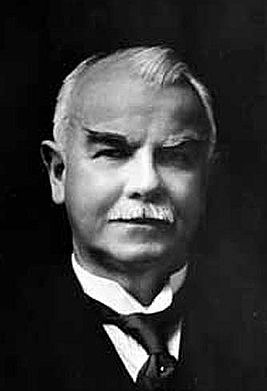

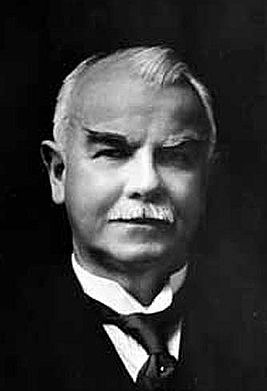

Sir James Alfred Ewing (1855-1935) is a Scottish physicist and engineer who is known for his work in the field of the magnetic properties of metals. In 1879 he designed a seismograph, close to modern. Being a close friend of Charles Parsons, Ewing helped him in developing the steam engine. In 1897, he took part in the sea trials of the experimental vessel Turbine, which developed the fastest speed at that time (35 knots).

Ewing eagerly took up the study of cryptographic materials stored in the library of the British Museum. Then he began studying codes at the city’s central post office, where copies of commercial codebooks were kept. In parallel with this, Ewing began to assemble a team, introducing four teachers from the naval colleges Osborne and Dartmouth to his activities. These were his friends, who are fluent in German. Together, they gathered in Ewing's office, studying incomprehensible lines of letters and numbers, having only the most general ideas about how to begin working to open ciphers.

By the middle of the autumn of 1914, the number of employees in the Ewing group had increased significantly; they were no longer located in his office. It took a more suitable and technically equipped room. As a result, the team of decoders moved into the old Admiralty building and became known as Room 40. It had a good location away from the busiest premises of the Admiralty and close enough to the operational department. Ewing became the director of Room 40, and the cryptographer Alistair Deniston was appointed his deputy.

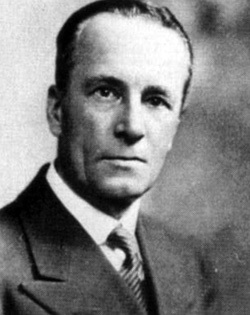

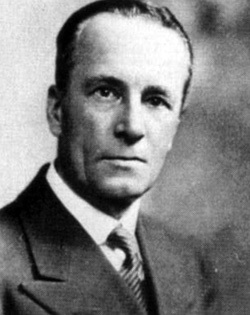

Alistair Guthrie Denniston (1881- 1961) - a British cryptographer, the first director of the secret service "Government Communications Center", who held this post in 1919 -1942.

All activities of Room 40 were kept in strict confidence, and very few officers in the Admiralty and on the ships of the English Navy knew of its existence. The ability to read radio reports of the German Navy gave staff more information about the operations and intentions of Admiral Scheer’s fleet than any other division of the Royal Navy had. Intercepted and decrypted text messages were sent to someone from a small group of dedicated officers of the operational management of the headquarters of the naval forces of Britain. For consideration of all messages and their interpretation from the point of view of information, Herbert Hope was chosen, who had previously worked on the routes of enemy ships. Hope was located in a small room, where he tried to understand the meaning of the received messages and make useful observations. But he received full access to information only over time, after a chance meeting with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir John Arbetnot Fisher.

A significant disadvantage of the organization of the work of Room 40 was that it could not act as an operational intelligence center. No messages processed by Room 40 could be sent without Oliver’s personal approval (with the exception of some approved by the First Lord or Admiralty Lord). The members of this organization understood that the information they had decrypted was not fully utilized due to the extreme secrecy and prohibitions to exchange it with other intelligence departments. As already mentioned, the transfer of instances prepared in Room 40 and only well-understood information was assigned to a small group of officers. But they did not have any special knowledge or the necessary skills in order to always correctly interpret the importance of transcripts and to manage their future fate in the most optimal way.

In 1917, some changes came - Room 40 stopped supplying raw information to the intelligence department and began transmitting all the actual materials in the form of thoughtful assessments of the intentions and character of the movements of German ships.

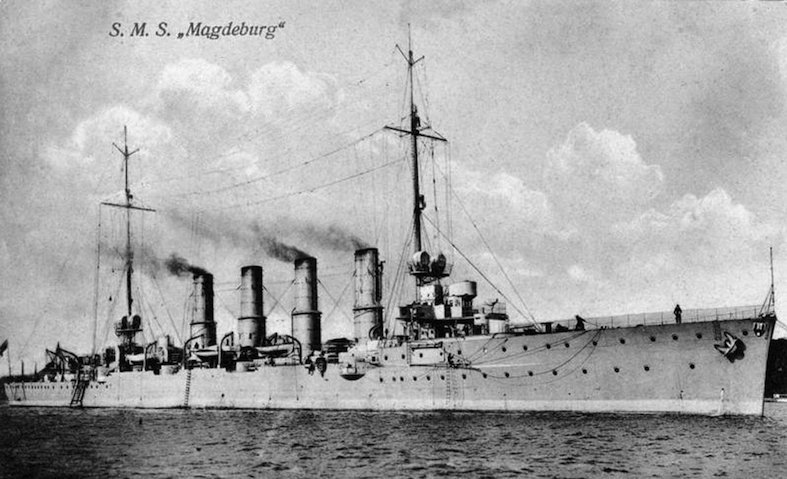

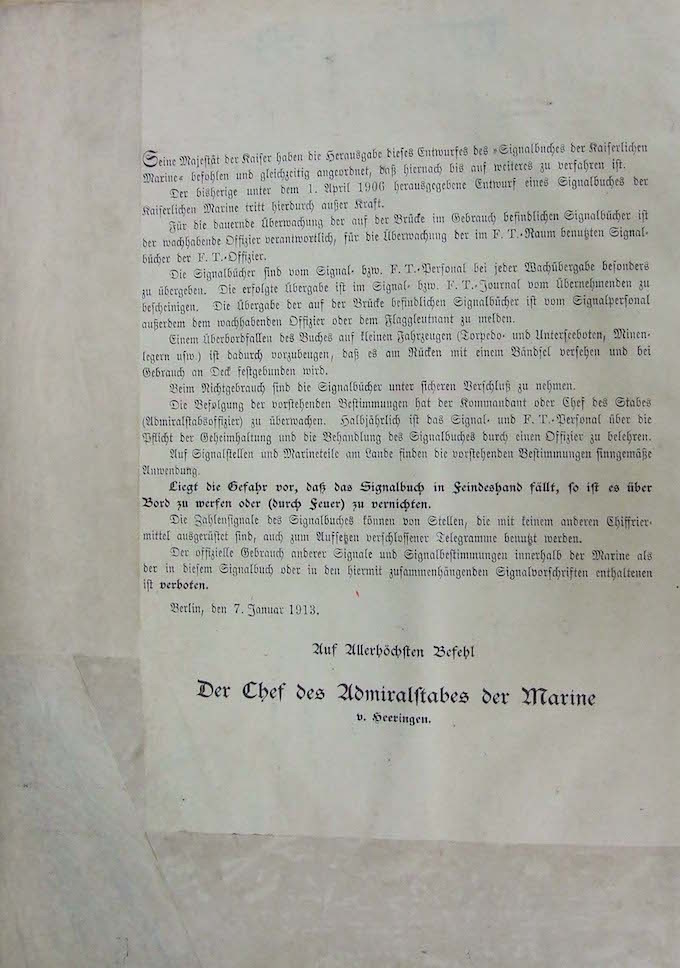

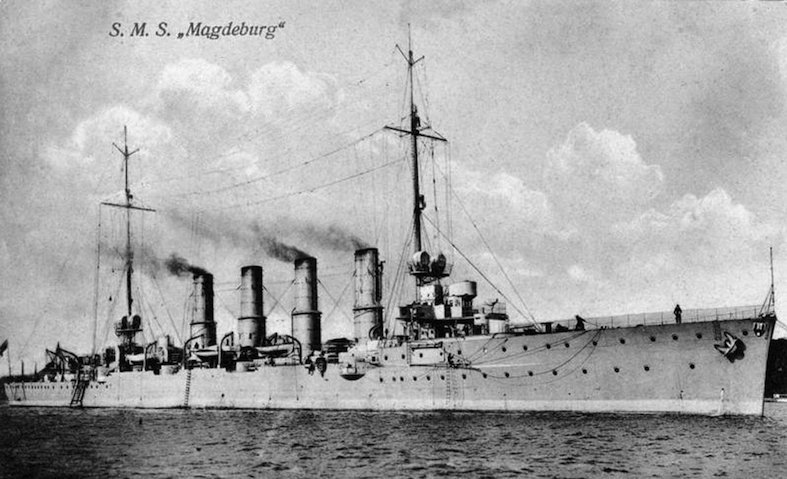

In 1914, Russia handed over to Great Britain the "Book of Signals of the Imperial Navy" (Signalbuch der Kaiserlich Marine, SKM), which was captured by Russian sailors on the German cruiser "Magdeburg". A British copy of the book was presented personally to the first Admiralty Lord Winston Leonard Churchill.

The cruiser "Magdeburg"

Getting SKM was the first breakthrough for Room 40 employees. In order to use the book, the current key was needed. The map of the Baltic states, the logbook and military diaries were also restored.

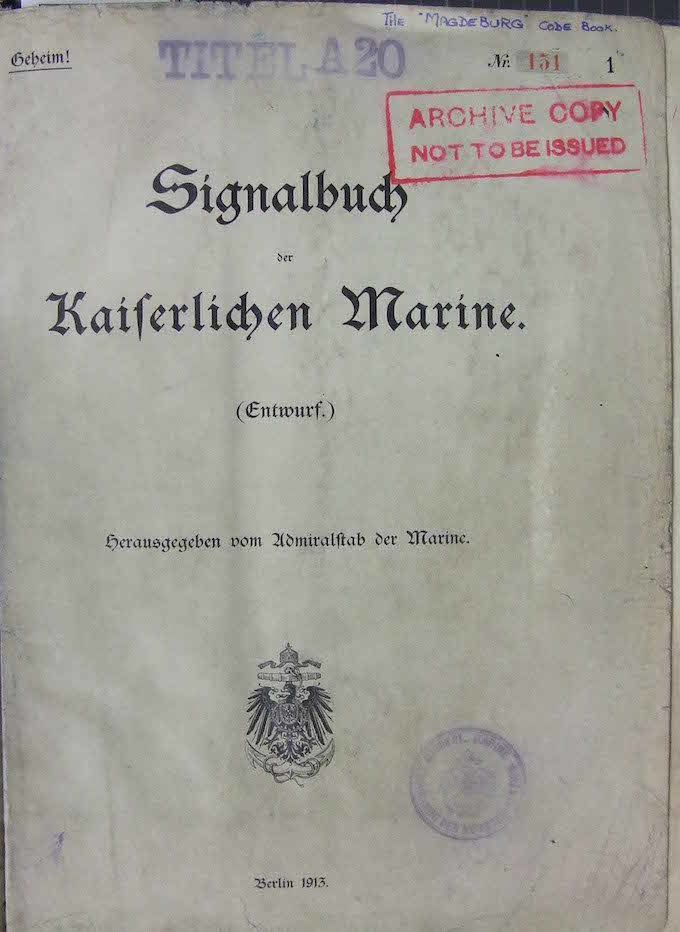

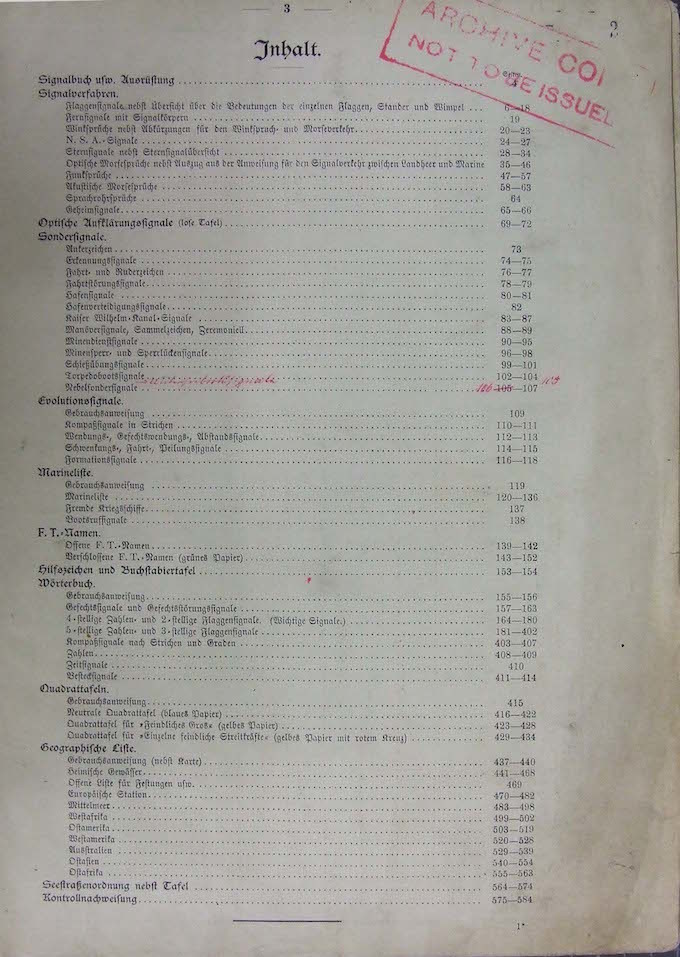

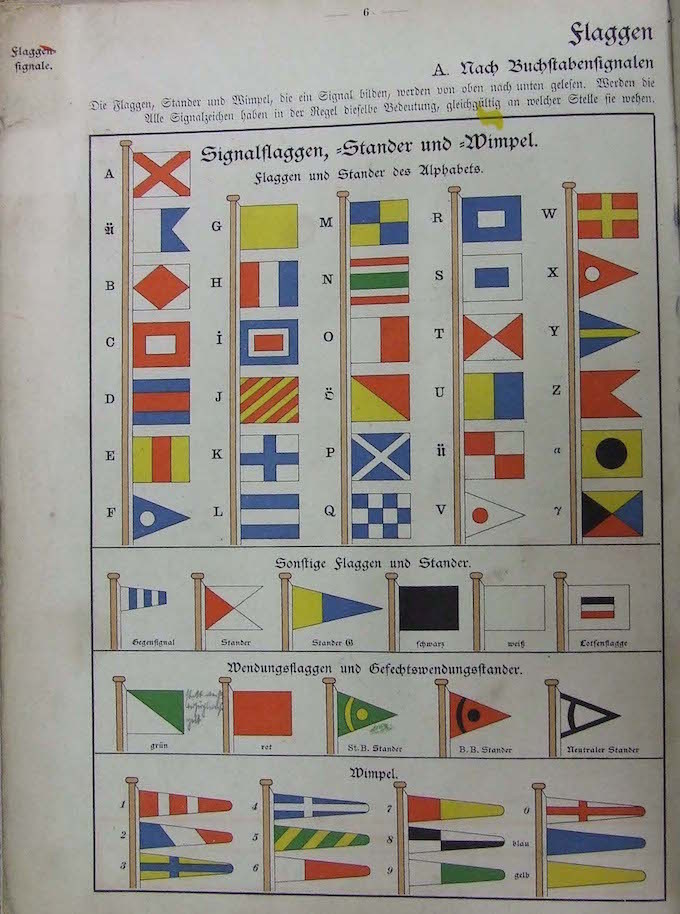

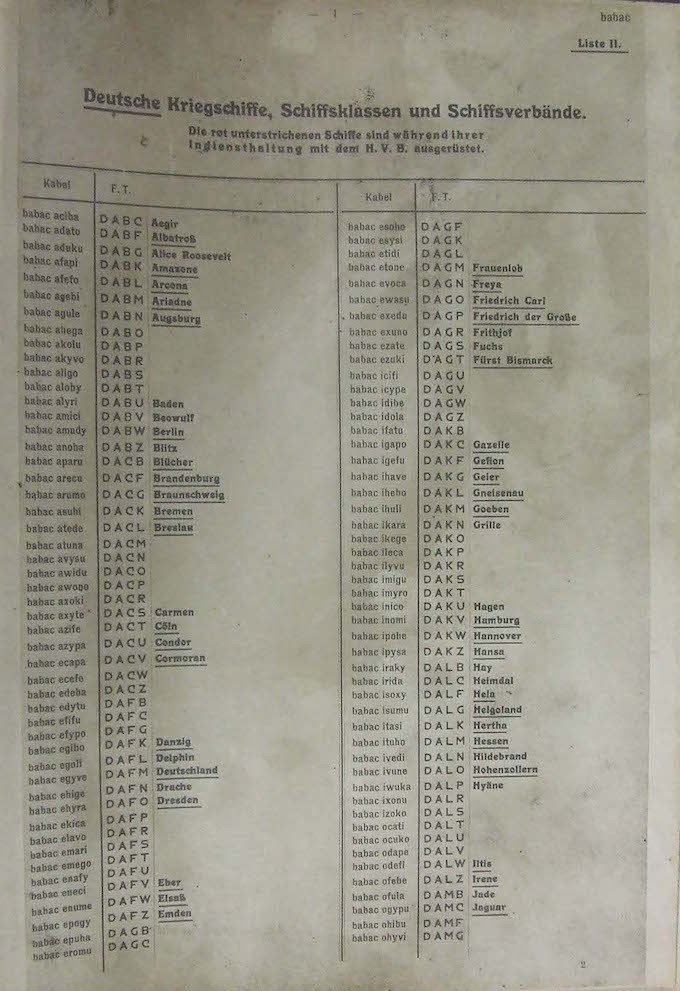

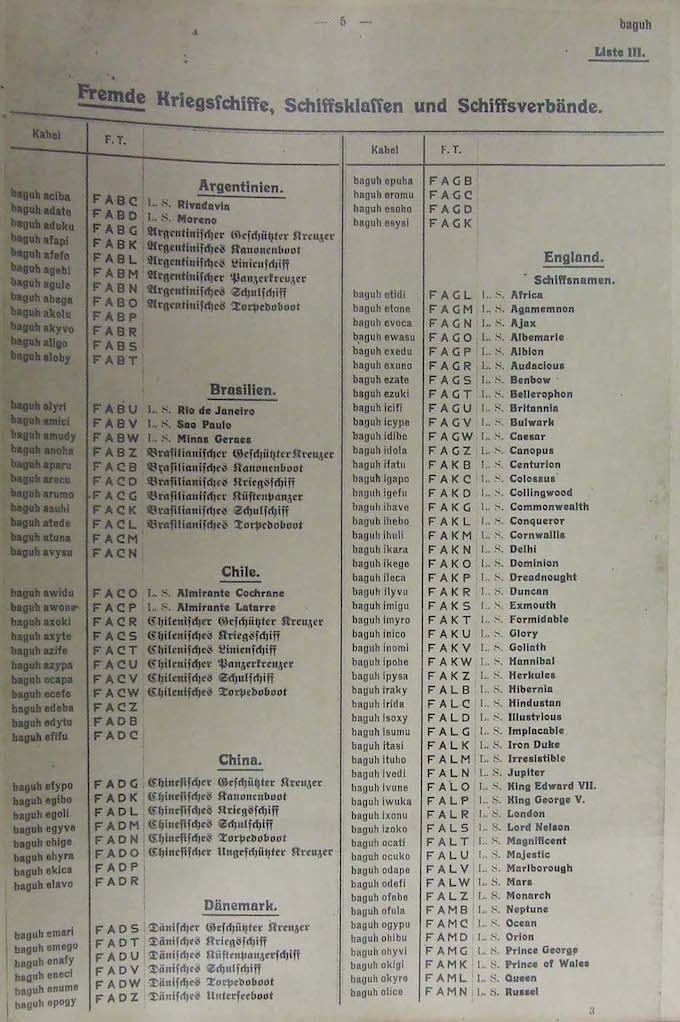

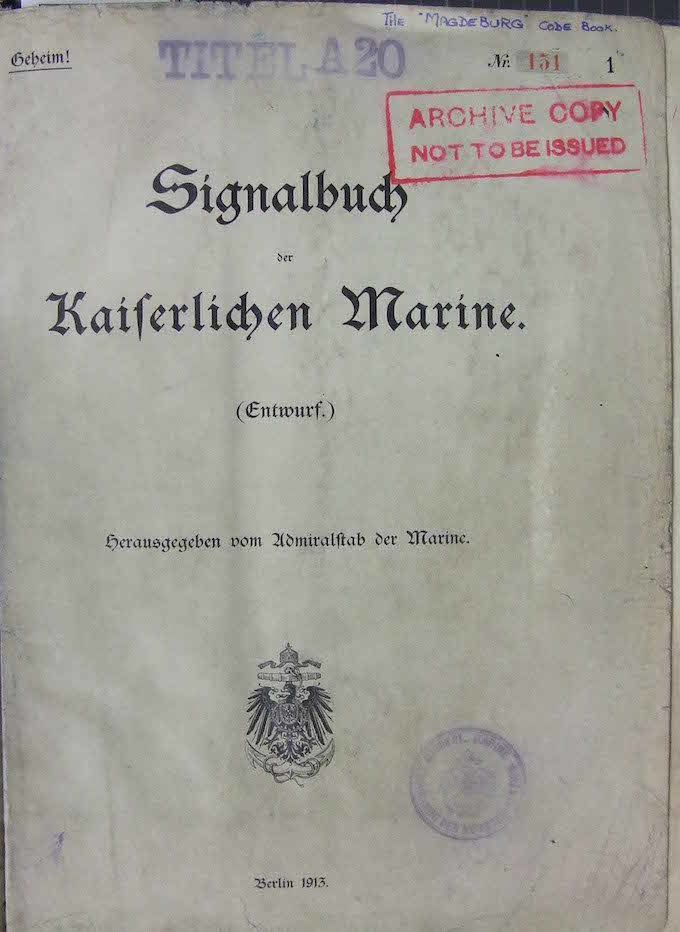

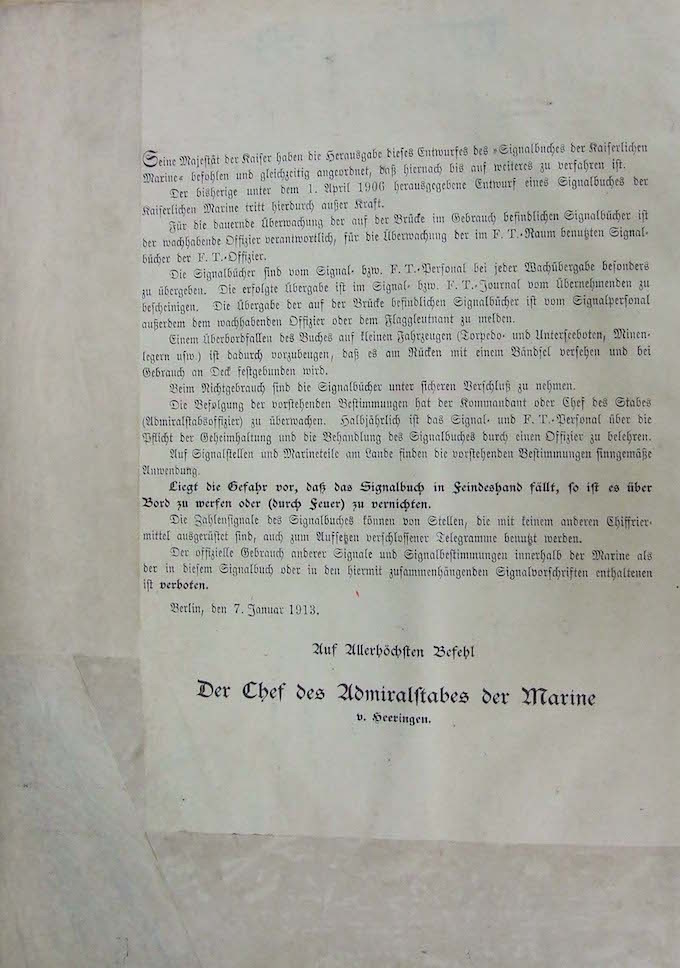

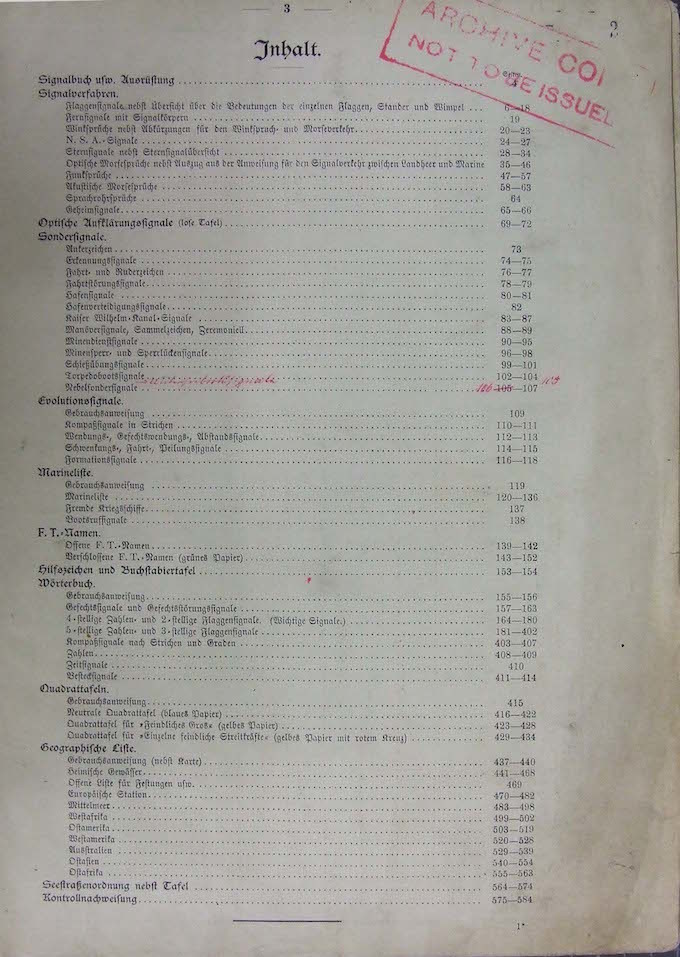

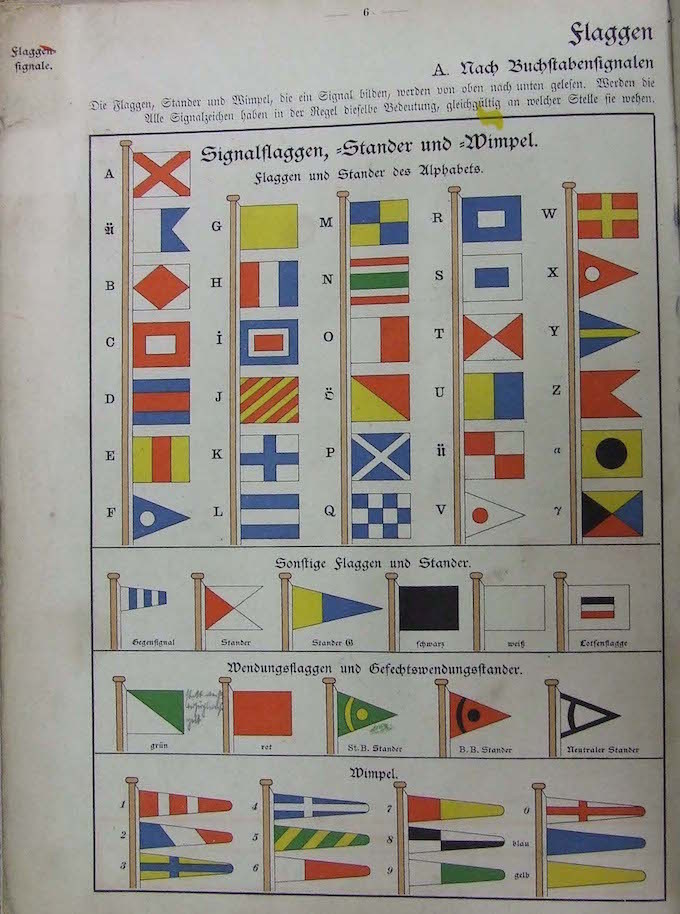

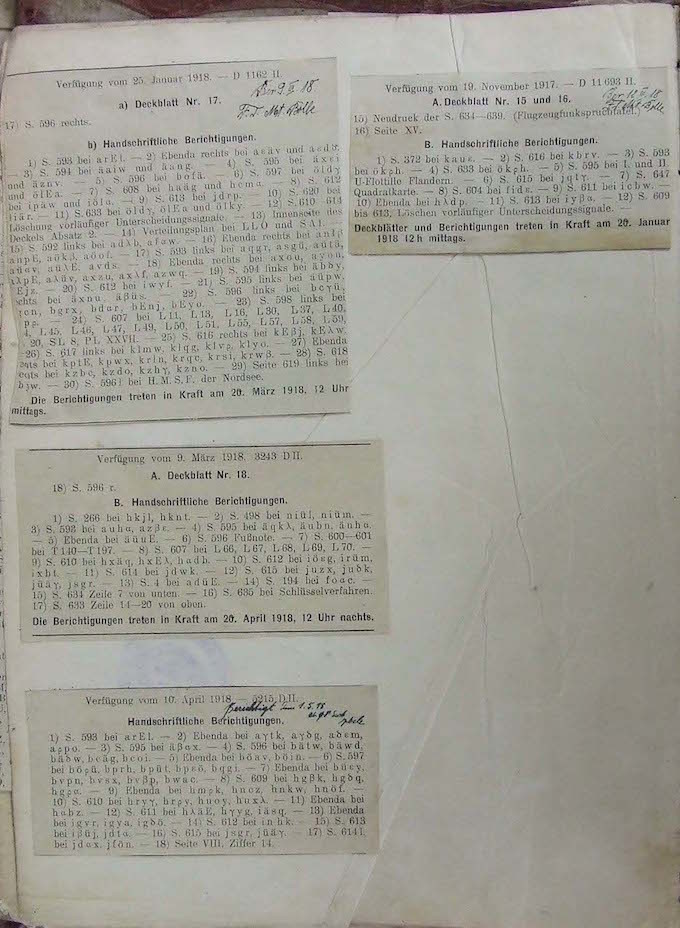

Sheets from the book SKM (more can be found here ):

By itself, the SKM was incomplete, since the messages were usually both encrypted and encoded. The German expert of the naval intelligence department, K.J.E. Rotter, was instructed to use SKM to interpret the intercepted encryption, most of which were meaningless when decrypted. The beginning of solving the problem was a series of transmitted messages from the transmitter German Norddeich. They were sequentially numbered and deciphered, appearing to be intelligence reports on the location of the allied ships. In fact, the cipher was cracked twice, because after a few days it changed and the general procedure for interpreting messages was determined. Encryption was a regular table replacing one letter with another in all messages.

The German fleet used SKM as a code during important actions. Transfer between ships took place in the form of simple combinations of signal flags or flashes of a lamp. SKM contained 34,000 instructions, each of which was represented by a different group of three letters. The signals used four characters that are not found in normal Morse code (because of which the interpreter had difficulties). But over time, cryptographers of Room 40 learned to recognize and use a standardized way of recording signals. Ships were identified by a group of three letters, starting with the beta symbol. Messages that are not covered by a predefined list could be spelled out using a lookup table for individual letters.

The huge size of the book was one of the reasons why it could not be easily changed. The code continued to be used until the summer of 1916. The valid lookup table that was used for encryption was generated by a mechanical device with thumbnails and letter compartments. Orders to change the key were sent by radio. The confusion that occurred during the change period led to the message being sent using a new cipher, and then repeated with the old one. Key changes did not occur often, only 6 times from March to the end of 1915, but since 1916 they have become frequent.

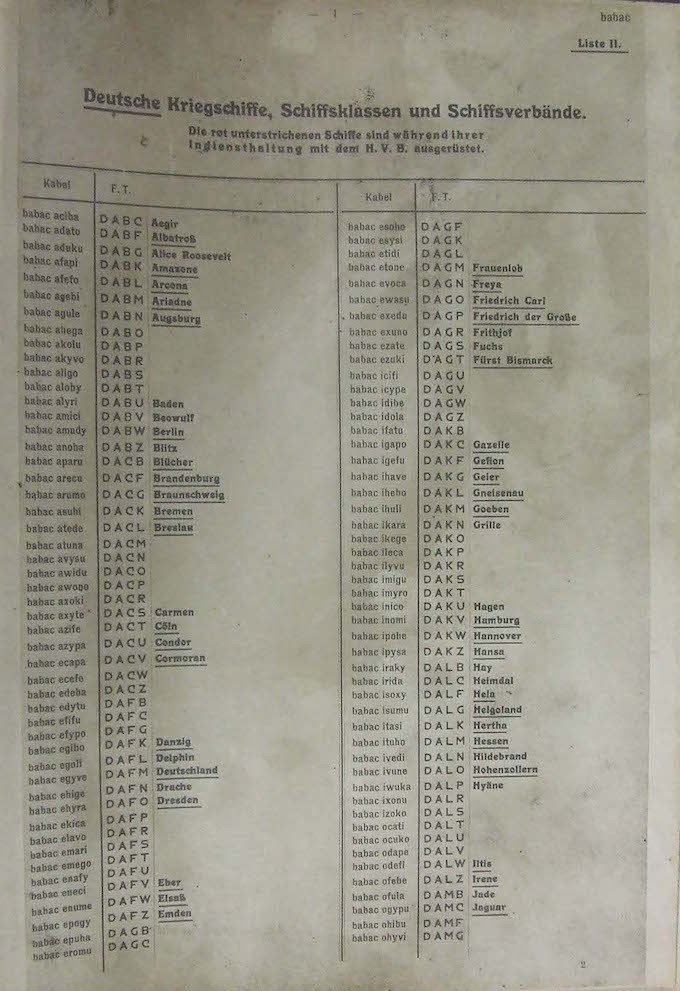

No less important code that was used by the German fleet was contained in the book Handelsverkehrsbuch (HVB). Its copy came to the British after the successful seizure of the German-Australian steamer "Hobart" in Australia on August 11, 1914. The German fleet used the code from the HVB code book to communicate with merchant ships, as well as inside the High Sea Fleet.

Sheets from the book HVB (more can be found here ):

HVB was released in 1913 for all warships with radio communications, naval commanders and coast stations, and also went to the main offices of eighteen German shipping companies to issue them to their own radio communications vessels. The code used 450,000 possible permutations of four letters. This gave an alternate representation of the same meaning, adding an additional ten letters grouped for use in messages. Most often, the code used patrol vessels. It was also used for normal tasks, such as entering and exiting the port. Submarines used a code with a more complex key.

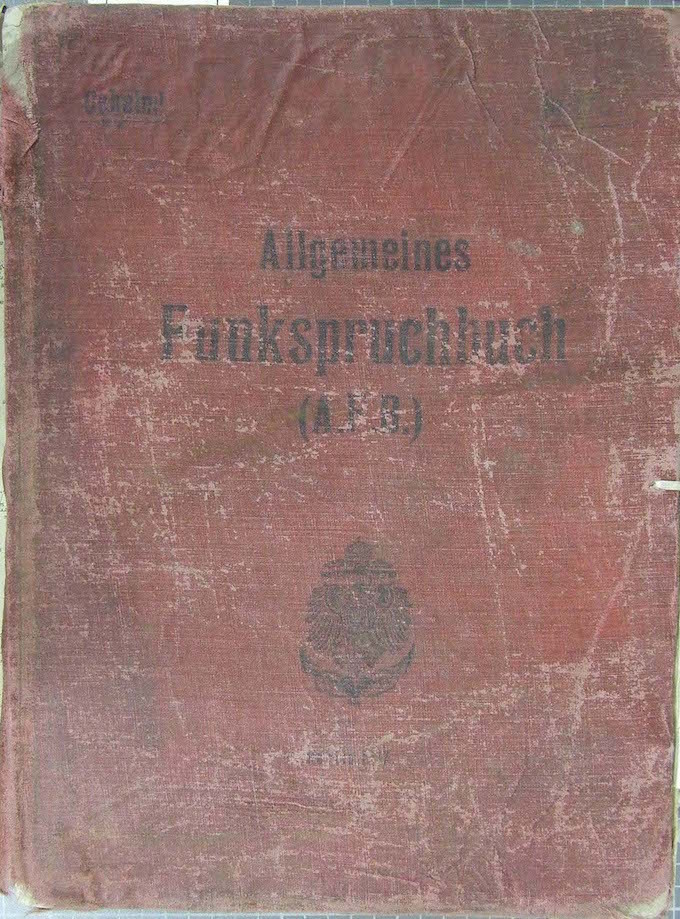

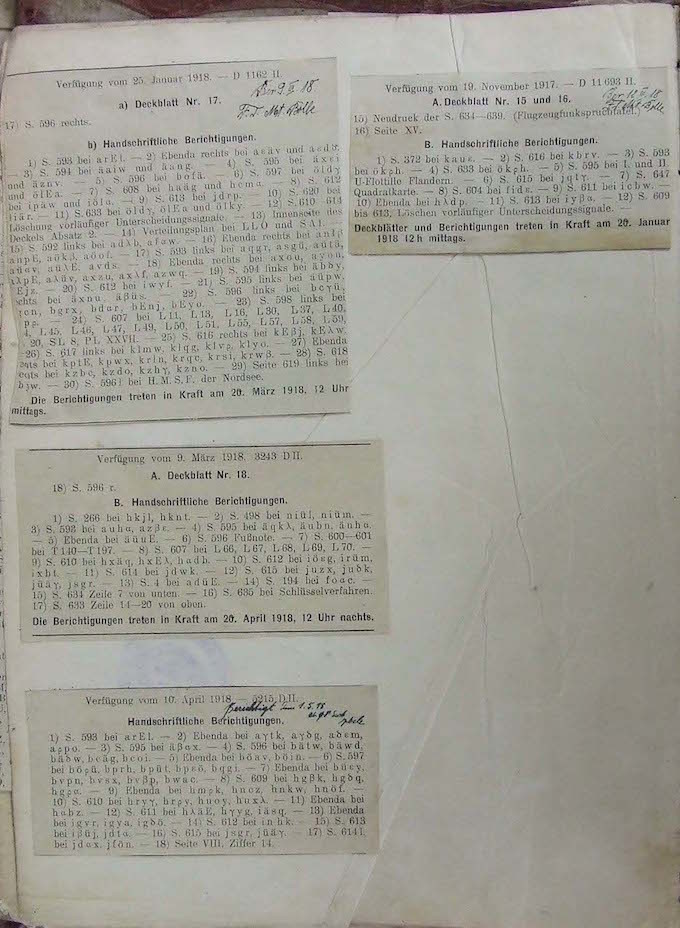

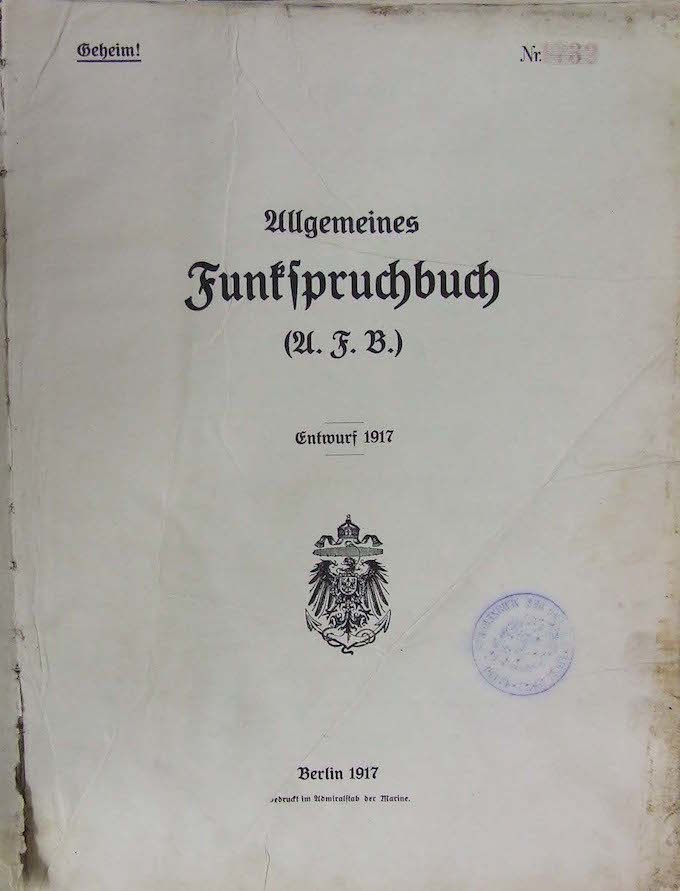

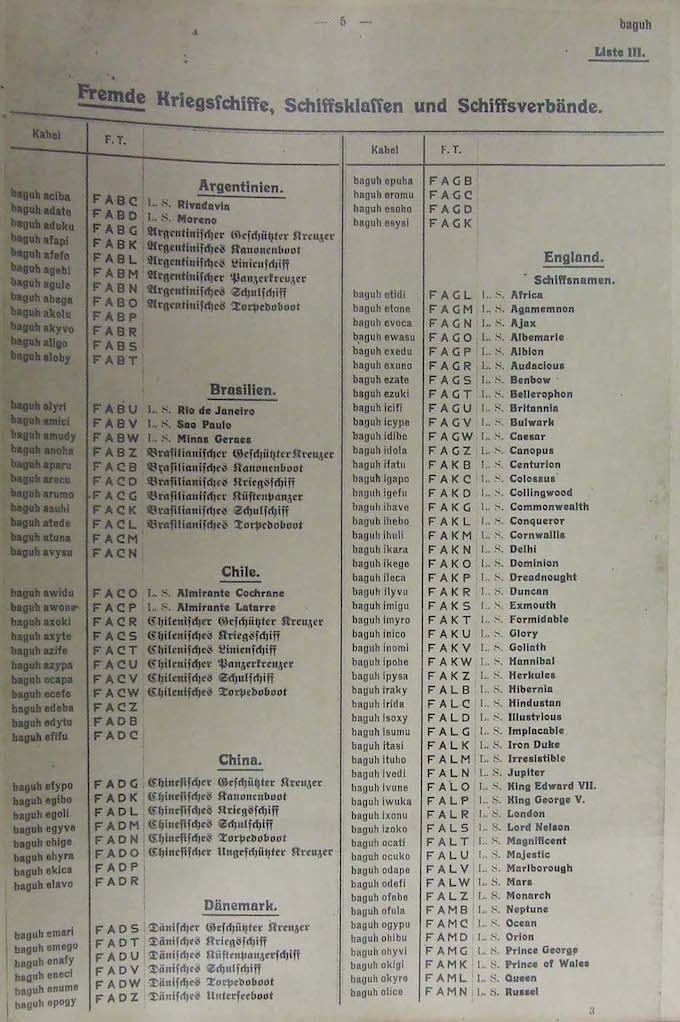

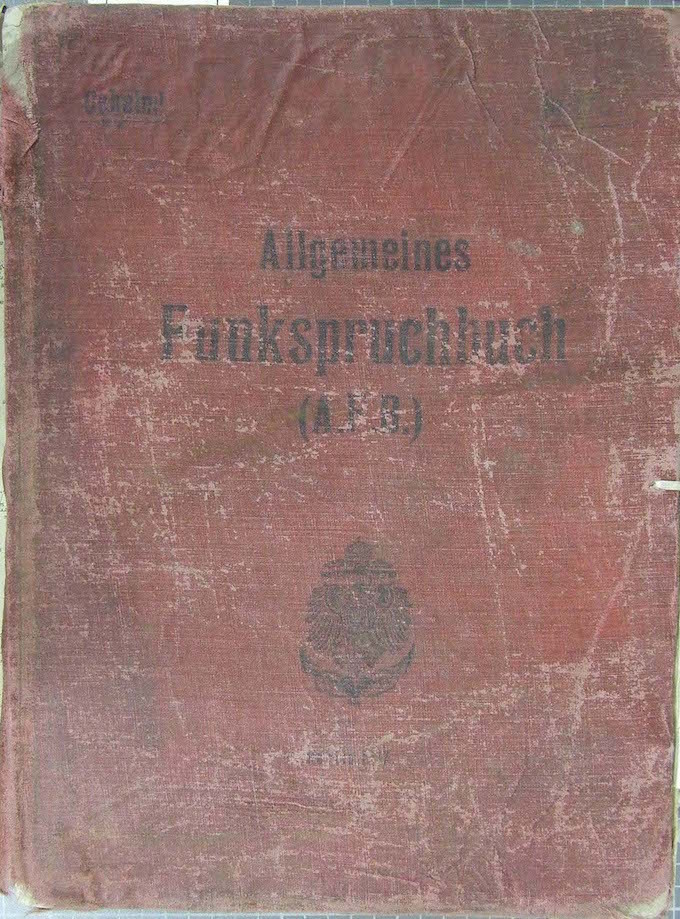

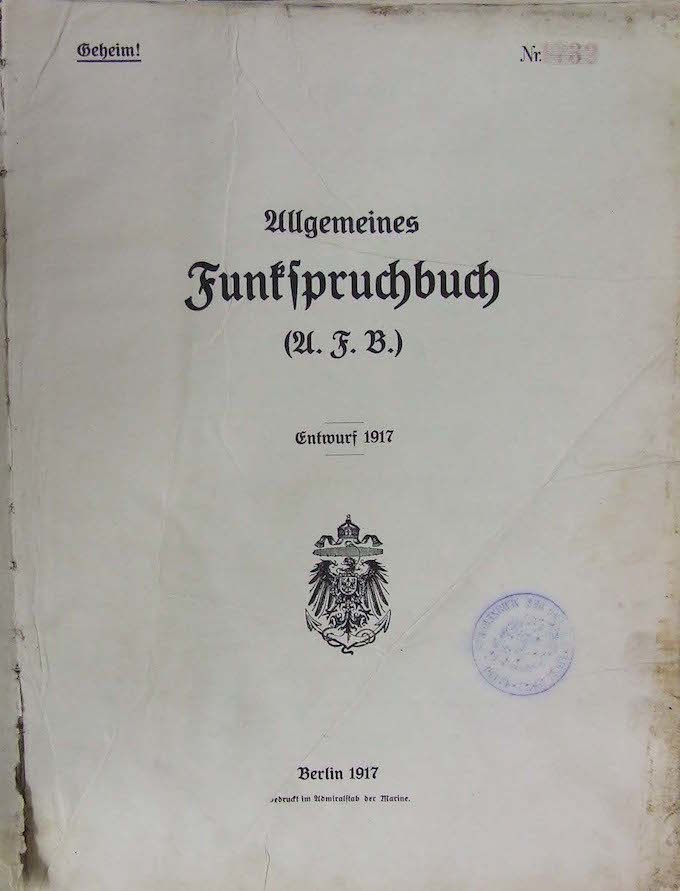

In 1914, it became known from radio communications that German intelligence learned about the transition of the HVB book to the British. But, all the less, the code was replaced only in 1916 with Allgemeinefunkspruchbuch (AFB) along with a new coding method. The British got a good idea of the new method of encrypting test signals before they entered it for real messages. This time even more organizations received a new code. Compared with its predecessor, AFB had more groups, but only with two letters. The first captured copy was taken from the downed "Zeppelin", while others were taken from the sunken submarines.

Sheets from the AFB book (more can be found here ):

In 1914, a copy of Germany’s third encryption book called “Verkehrsbuch” (VB) got into Room 40. It was restored after the sinking of the German destroyer S119 in the battle near the island of Texel. The commander threw overboard the secret documents in the lead box and it was believed that they were lost. But a month later, the box was dragged out and transferred to Room 40 employees for decryption. The box contained a copy of the “Verkehrsbuch” used by the commander of the German fleet. The code had 100,000 groups of 5 digits, each of which had a special meaning. It was used to encrypt telegrams sent abroad to warships and naval attaches, embassies and consulates.

The code from VB opened access to communications between naval attaches in Berlin, Madrid, Washington, Buenos Aires, Beijing and Constantinople.

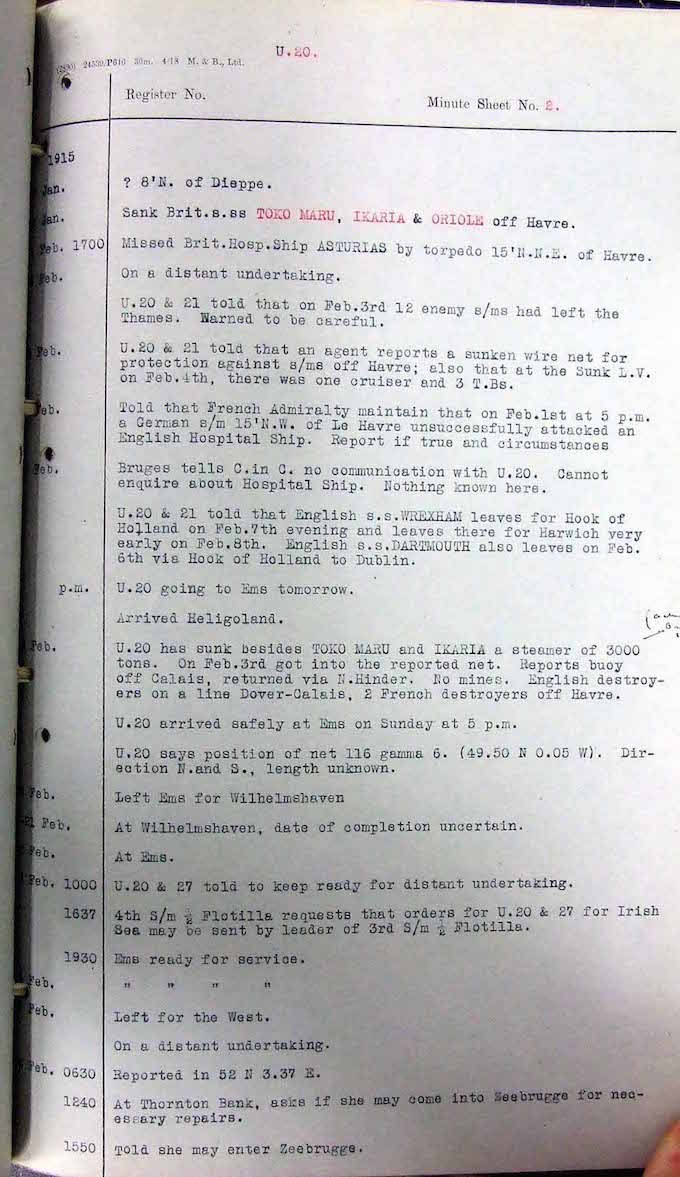

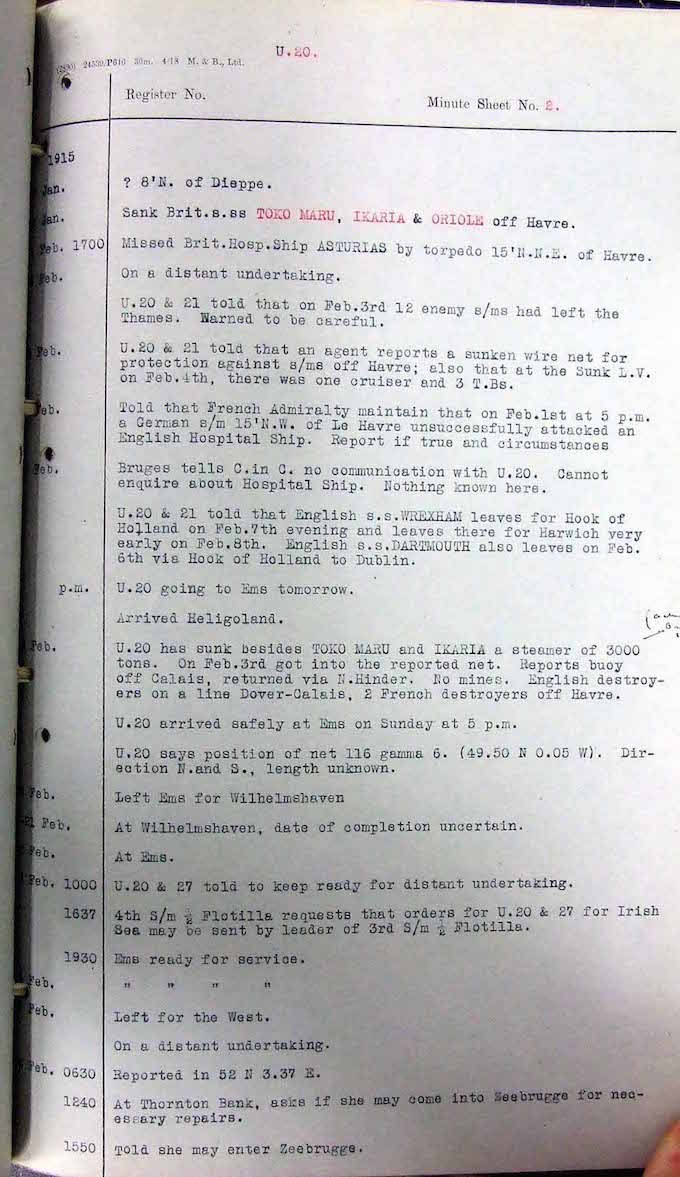

Declassified by the team of Room 40, the magazine of the German submarine U20 (located in the National Archives of London)

Room 40 regularly intercepted messages and possessed very accurate information about the position of the German ships. Nevertheless, the British ships received clear instructions indicating to use the radio as seldom as possible and at the lowest frequency.

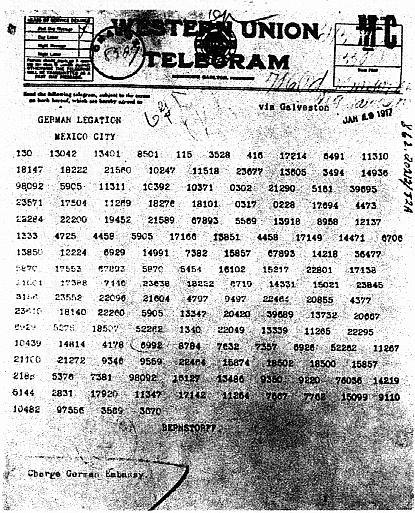

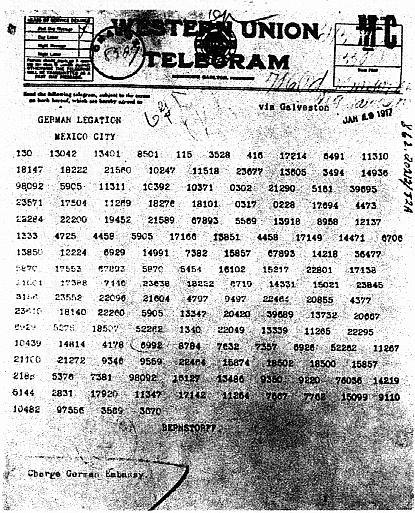

The most significant achievement of Room 40 in the history of naval battles was the decoding of the Zimmermann Telegram. It dated January 19, 1917 and traveled from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany to Ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt in Mexico.

Under the guise of a diplomatic message, the telegram was transmitted by radio and telegraph through neutral states: Sweden and the USA. Germany had to use the telegraph channels of Britain and America. The Germans were forced to take such a risk because they did not have direct telegraph access to the western hemisphere, as the British cut their transatlantic cables and destroyed the transmitting stations.

Telegram Zimmerman

The text of the telegram reported that German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman offered Mexico the territory of the United States (Arizona, New Mexico and Texas), if she took part in the war as an ally of Germany. The British government understood the value of this message. But it was worth solving two problems. First, explain to the Americans how the Telegram was received, without disclosing the fact that British intelligence is checking the diplomatic mail of neutral countries. Secondly, to give a public explanation of how the Telegram was deciphered, but so that Germany did not suspect anything (that the codes have been cracked).

The first problem was solved when the British received the cipher text of the Telegram from the telegraph office in Mexico. The German ambassador sent a message from Washington to Mexico with a commercial telegraph, so the Mexican telegraph office turned out to be a copy of the encrypted text. A British agent obtained this copy and handed it over to the Americans. The text was encrypted with code 13040, a sample of which Britain had acquired in Mesopotamia. The Germans encrypted their messages using the usual Foreign Ministry algorithm and the key number 0075, which experts in Room 40 had already partially cracked. The algorithm included the replacement of words (encoding), as well as the replacement of letters (encryption). This is a common practice that was used in Germany in another encryption method - the ADFGVX cipher.

According to the “official” version, the decrypted text of the Telegram was stolen by the British in Mexico and handed over to the Americans. And on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany.

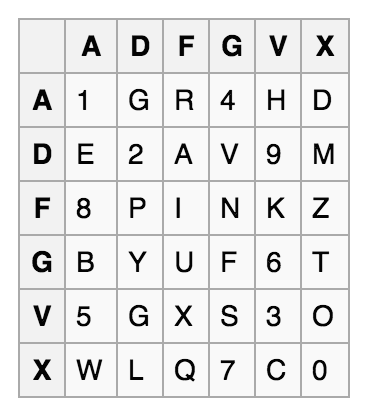

The font developer is Colonel Fritz Nebel, Communications Officer. The peculiarity of this cipher was that it was built on the combination of the basic operations of replacement and permutation. The part of the cipher that corresponds to the replacement was based on Polybius square .

The code contains only the letters “A”, “D”, “F”, “G” and “X” (hence the name of the cipher). The choice of these letters was not accidental. If you represent them as dots and dashes of Morse code, then they will differ significantly from each other. In fact - it was the square of Polybius, which in a certain order fit the Latin alphabet. Since 1918, the letter “V” has been added, complicating the cipher and increasing the encryption grid to 36 characters. This allowed to include in the plaintext numbers from 0 to 9, in addition the letters I and J were encrypted in different ways.

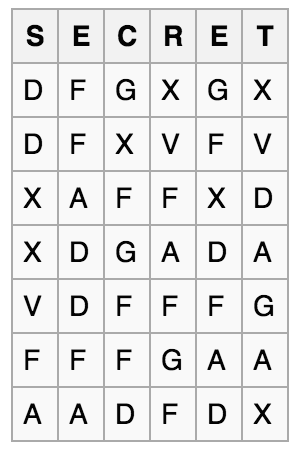

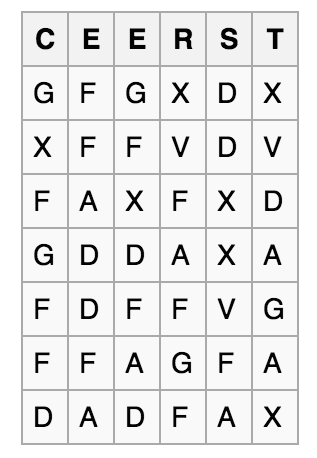

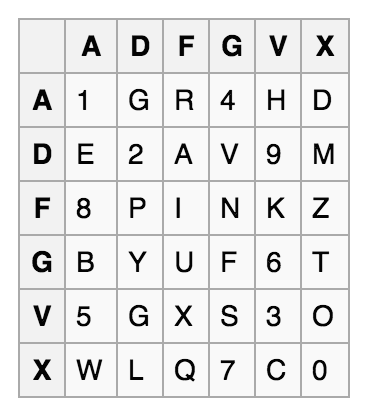

The cipher was based on 6 letters: “A”, “D”, “F”, “G”, “V” and “X”. The cipher exchange table for ADFGX was a 5 x 5 matrix, and for ADFGVX it was 6 x 6. Rows and columns were denoted by the letters in the cipher name. The arrangement of the elements in the table was part of the key.

The shifrozamena for the letter of the source text consisted of the letters denoting the row and column at the intersection of which it was located.

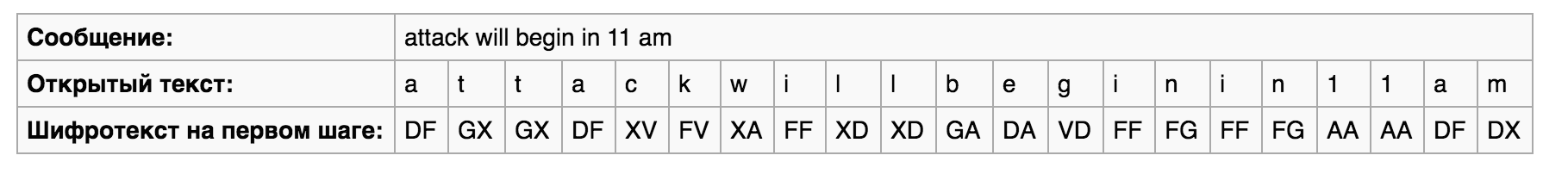

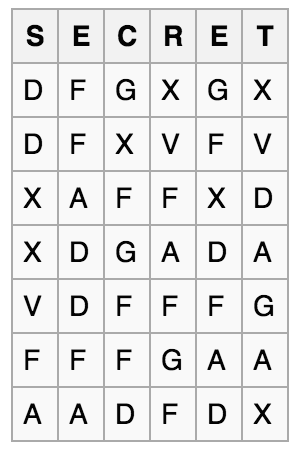

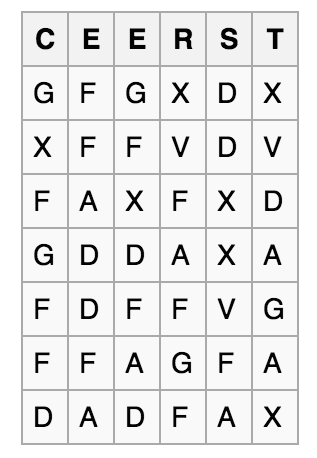

At the second stage, to perform the permutation, the received set of cipro-replacement fit line by line from top to bottom into the table. The number of columns was strictly defined in the table or it corresponded to the number of letters in the keyword. The numbering of the columns was either pre-negotiated by the parties or corresponded to the position of the letters of the keyword in the alphabet. A new table was created with the keyword in the top row.

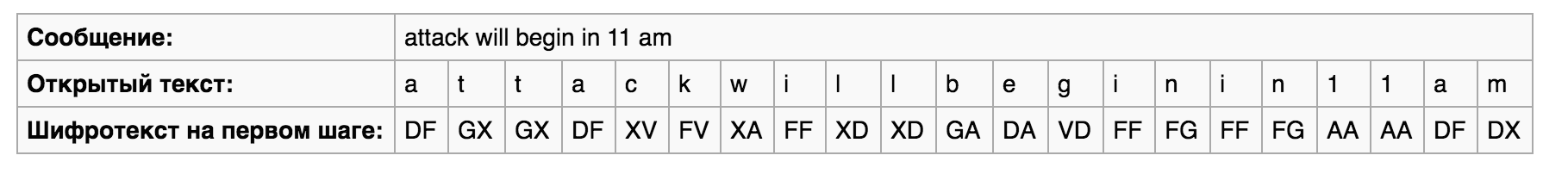

For example, consider the message in English: “attack will begin in 11 am”. As a key, you can take the word "SECRET". But as a rule, longer keywords or phrases were used.

The table columns were sorted alphabetically.

Further, the letters were written out from the columns in accordance with their numbering, in this case the reading took place in columns, and the letters were combined into five-letter groups. Thus, the final form of the ciphertext looked like this:

GXFGFFDFFADDFAGFXDFAD XVFAFGFDDXXVFAXVDAGAX

In order to restore the source code, it was necessary to perform actions that are inverse to encryption. The sequence of columns could be brought to the original order using a keyword. Knowing the locations of the characters in the source table helped decipher the text.

Telegram text:

The German command began to adjust its ciphers only from 1916, changing codes every month (and later even daily). But the principle of encryption remained the same. And by this time, specialists from Room 40 had already become completely familiar with the German encryption system, speeding up the process of decrypting a message. Sometimes the content of German radiograms in London was recognized before their addressee.

Old Admiralty

In 1919, Room 40 was disbanded and on its base, as well as on the basis of the cryptographic intelligence unit of the British Army MI1b (Eng. Military Intelligence, Section 1), the Government School of Coding and Encryption (GC & CS) was formed. During World War II, this school was located in Bletchley Park and subsequently became an electronic intelligence service independent of military intelligence. In 1946, it was renamed the Center for Government Communications (Eng. Government Communications Headquarters, GCHQ), and from 1951 to 1952 it was moved to Cheltenham. But the actual room 40 is still located on the first floor of the Whitehall Admiralty Building in London.

Room 40 was also known as 40 SB. (Old building) and was a division of the leading cryptographic body of Great Britain during the First World War - the British Admiralty. The organization was formed in October 1914, shortly after the start of the war. Room 40 got its name thanks to the room number in the old building of the Admiralty, where it was located. For most of its existence, this organization was a cryptogram analysis and decryption bureau. Its employees decrypted about 15,000 German messages.

')

Making Room 40

In 1911, the department of the Defense Committee of the Empire for communication, it was decided - in the event of the outbreak of war with Germany, you must immediately destroy the German underwater communications. On the morning of August 5, 1914, the cable vessel Alert identified and cut off 5 German transatlantic cables that reached the English Channel. Shortly thereafter, the 6 cables that ran between Britain and Germany were also cut off. As a result, increased the flow of messages transmitted by radio. Codes and ciphers were used to hide their content. But to decrypt such messages, neither the UK nor Germany had the relevant organizations. Messages that could be intercepted were sent to the Admiralty intelligence department, which was led by Rear Admiral Henry Oliver since 1913. But there were also no employees who could crack the code. Then Oliver turned to his friend, an engineer with radio communications experience, Sir Alfred Eingu, and asked to form a group to decrypt messages.

Sir James Alfred Ewing (1855-1935) is a Scottish physicist and engineer who is known for his work in the field of the magnetic properties of metals. In 1879 he designed a seismograph, close to modern. Being a close friend of Charles Parsons, Ewing helped him in developing the steam engine. In 1897, he took part in the sea trials of the experimental vessel Turbine, which developed the fastest speed at that time (35 knots).

Ewing eagerly took up the study of cryptographic materials stored in the library of the British Museum. Then he began studying codes at the city’s central post office, where copies of commercial codebooks were kept. In parallel with this, Ewing began to assemble a team, introducing four teachers from the naval colleges Osborne and Dartmouth to his activities. These were his friends, who are fluent in German. Together, they gathered in Ewing's office, studying incomprehensible lines of letters and numbers, having only the most general ideas about how to begin working to open ciphers.

By the middle of the autumn of 1914, the number of employees in the Ewing group had increased significantly; they were no longer located in his office. It took a more suitable and technically equipped room. As a result, the team of decoders moved into the old Admiralty building and became known as Room 40. It had a good location away from the busiest premises of the Admiralty and close enough to the operational department. Ewing became the director of Room 40, and the cryptographer Alistair Deniston was appointed his deputy.

Alistair Guthrie Denniston (1881- 1961) - a British cryptographer, the first director of the secret service "Government Communications Center", who held this post in 1919 -1942.

All activities of Room 40 were kept in strict confidence, and very few officers in the Admiralty and on the ships of the English Navy knew of its existence. The ability to read radio reports of the German Navy gave staff more information about the operations and intentions of Admiral Scheer’s fleet than any other division of the Royal Navy had. Intercepted and decrypted text messages were sent to someone from a small group of dedicated officers of the operational management of the headquarters of the naval forces of Britain. For consideration of all messages and their interpretation from the point of view of information, Herbert Hope was chosen, who had previously worked on the routes of enemy ships. Hope was located in a small room, where he tried to understand the meaning of the received messages and make useful observations. But he received full access to information only over time, after a chance meeting with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir John Arbetnot Fisher.

A significant disadvantage of the organization of the work of Room 40 was that it could not act as an operational intelligence center. No messages processed by Room 40 could be sent without Oliver’s personal approval (with the exception of some approved by the First Lord or Admiralty Lord). The members of this organization understood that the information they had decrypted was not fully utilized due to the extreme secrecy and prohibitions to exchange it with other intelligence departments. As already mentioned, the transfer of instances prepared in Room 40 and only well-understood information was assigned to a small group of officers. But they did not have any special knowledge or the necessary skills in order to always correctly interpret the importance of transcripts and to manage their future fate in the most optimal way.

In 1917, some changes came - Room 40 stopped supplying raw information to the intelligence department and began transmitting all the actual materials in the form of thoughtful assessments of the intentions and character of the movements of German ships.

SKM encryption book capture

In 1914, Russia handed over to Great Britain the "Book of Signals of the Imperial Navy" (Signalbuch der Kaiserlich Marine, SKM), which was captured by Russian sailors on the German cruiser "Magdeburg". A British copy of the book was presented personally to the first Admiralty Lord Winston Leonard Churchill.

The cruiser "Magdeburg"

Getting SKM was the first breakthrough for Room 40 employees. In order to use the book, the current key was needed. The map of the Baltic states, the logbook and military diaries were also restored.

Sheets from the book SKM (more can be found here ):

By itself, the SKM was incomplete, since the messages were usually both encrypted and encoded. The German expert of the naval intelligence department, K.J.E. Rotter, was instructed to use SKM to interpret the intercepted encryption, most of which were meaningless when decrypted. The beginning of solving the problem was a series of transmitted messages from the transmitter German Norddeich. They were sequentially numbered and deciphered, appearing to be intelligence reports on the location of the allied ships. In fact, the cipher was cracked twice, because after a few days it changed and the general procedure for interpreting messages was determined. Encryption was a regular table replacing one letter with another in all messages.

The German fleet used SKM as a code during important actions. Transfer between ships took place in the form of simple combinations of signal flags or flashes of a lamp. SKM contained 34,000 instructions, each of which was represented by a different group of three letters. The signals used four characters that are not found in normal Morse code (because of which the interpreter had difficulties). But over time, cryptographers of Room 40 learned to recognize and use a standardized way of recording signals. Ships were identified by a group of three letters, starting with the beta symbol. Messages that are not covered by a predefined list could be spelled out using a lookup table for individual letters.

The huge size of the book was one of the reasons why it could not be easily changed. The code continued to be used until the summer of 1916. The valid lookup table that was used for encryption was generated by a mechanical device with thumbnails and letter compartments. Orders to change the key were sent by radio. The confusion that occurred during the change period led to the message being sent using a new cipher, and then repeated with the old one. Key changes did not occur often, only 6 times from March to the end of 1915, but since 1916 they have become frequent.

HVB Encryption Book Capture

No less important code that was used by the German fleet was contained in the book Handelsverkehrsbuch (HVB). Its copy came to the British after the successful seizure of the German-Australian steamer "Hobart" in Australia on August 11, 1914. The German fleet used the code from the HVB code book to communicate with merchant ships, as well as inside the High Sea Fleet.

Sheets from the book HVB (more can be found here ):

HVB was released in 1913 for all warships with radio communications, naval commanders and coast stations, and also went to the main offices of eighteen German shipping companies to issue them to their own radio communications vessels. The code used 450,000 possible permutations of four letters. This gave an alternate representation of the same meaning, adding an additional ten letters grouped for use in messages. Most often, the code used patrol vessels. It was also used for normal tasks, such as entering and exiting the port. Submarines used a code with a more complex key.

In 1914, it became known from radio communications that German intelligence learned about the transition of the HVB book to the British. But, all the less, the code was replaced only in 1916 with Allgemeinefunkspruchbuch (AFB) along with a new coding method. The British got a good idea of the new method of encrypting test signals before they entered it for real messages. This time even more organizations received a new code. Compared with its predecessor, AFB had more groups, but only with two letters. The first captured copy was taken from the downed "Zeppelin", while others were taken from the sunken submarines.

Sheets from the AFB book (more can be found here ):

VB Encryption Book Capture

In 1914, a copy of Germany’s third encryption book called “Verkehrsbuch” (VB) got into Room 40. It was restored after the sinking of the German destroyer S119 in the battle near the island of Texel. The commander threw overboard the secret documents in the lead box and it was believed that they were lost. But a month later, the box was dragged out and transferred to Room 40 employees for decryption. The box contained a copy of the “Verkehrsbuch” used by the commander of the German fleet. The code had 100,000 groups of 5 digits, each of which had a special meaning. It was used to encrypt telegrams sent abroad to warships and naval attaches, embassies and consulates.

The code from VB opened access to communications between naval attaches in Berlin, Madrid, Washington, Buenos Aires, Beijing and Constantinople.

Declassified by the team of Room 40, the magazine of the German submarine U20 (located in the National Archives of London)

Room 40 regularly intercepted messages and possessed very accurate information about the position of the German ships. Nevertheless, the British ships received clear instructions indicating to use the radio as seldom as possible and at the lowest frequency.

Telegram Zimmerman

The most significant achievement of Room 40 in the history of naval battles was the decoding of the Zimmermann Telegram. It dated January 19, 1917 and traveled from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany to Ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt in Mexico.

Under the guise of a diplomatic message, the telegram was transmitted by radio and telegraph through neutral states: Sweden and the USA. Germany had to use the telegraph channels of Britain and America. The Germans were forced to take such a risk because they did not have direct telegraph access to the western hemisphere, as the British cut their transatlantic cables and destroyed the transmitting stations.

Telegram Zimmerman

The text of the telegram reported that German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman offered Mexico the territory of the United States (Arizona, New Mexico and Texas), if she took part in the war as an ally of Germany. The British government understood the value of this message. But it was worth solving two problems. First, explain to the Americans how the Telegram was received, without disclosing the fact that British intelligence is checking the diplomatic mail of neutral countries. Secondly, to give a public explanation of how the Telegram was deciphered, but so that Germany did not suspect anything (that the codes have been cracked).

The first problem was solved when the British received the cipher text of the Telegram from the telegraph office in Mexico. The German ambassador sent a message from Washington to Mexico with a commercial telegraph, so the Mexican telegraph office turned out to be a copy of the encrypted text. A British agent obtained this copy and handed it over to the Americans. The text was encrypted with code 13040, a sample of which Britain had acquired in Mesopotamia. The Germans encrypted their messages using the usual Foreign Ministry algorithm and the key number 0075, which experts in Room 40 had already partially cracked. The algorithm included the replacement of words (encoding), as well as the replacement of letters (encryption). This is a common practice that was used in Germany in another encryption method - the ADFGVX cipher.

According to the “official” version, the decrypted text of the Telegram was stolen by the British in Mexico and handed over to the Americans. And on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany.

Code ADFGVX

The font developer is Colonel Fritz Nebel, Communications Officer. The peculiarity of this cipher was that it was built on the combination of the basic operations of replacement and permutation. The part of the cipher that corresponds to the replacement was based on Polybius square .

The code contains only the letters “A”, “D”, “F”, “G” and “X” (hence the name of the cipher). The choice of these letters was not accidental. If you represent them as dots and dashes of Morse code, then they will differ significantly from each other. In fact - it was the square of Polybius, which in a certain order fit the Latin alphabet. Since 1918, the letter “V” has been added, complicating the cipher and increasing the encryption grid to 36 characters. This allowed to include in the plaintext numbers from 0 to 9, in addition the letters I and J were encrypted in different ways.

The cipher was based on 6 letters: “A”, “D”, “F”, “G”, “V” and “X”. The cipher exchange table for ADFGX was a 5 x 5 matrix, and for ADFGVX it was 6 x 6. Rows and columns were denoted by the letters in the cipher name. The arrangement of the elements in the table was part of the key.

The shifrozamena for the letter of the source text consisted of the letters denoting the row and column at the intersection of which it was located.

At the second stage, to perform the permutation, the received set of cipro-replacement fit line by line from top to bottom into the table. The number of columns was strictly defined in the table or it corresponded to the number of letters in the keyword. The numbering of the columns was either pre-negotiated by the parties or corresponded to the position of the letters of the keyword in the alphabet. A new table was created with the keyword in the top row.

For example, consider the message in English: “attack will begin in 11 am”. As a key, you can take the word "SECRET". But as a rule, longer keywords or phrases were used.

The table columns were sorted alphabetically.

Further, the letters were written out from the columns in accordance with their numbering, in this case the reading took place in columns, and the letters were combined into five-letter groups. Thus, the final form of the ciphertext looked like this:

GXFGFFDFFADDFAGFXDFAD XVFAFGFDDXXVFAXVDAGAX

In order to restore the source code, it was necessary to perform actions that are inverse to encryption. The sequence of columns could be brought to the original order using a keyword. Knowing the locations of the characters in the source table helped decipher the text.

Telegram text:

We intend to begin a merciless submarine war on February 1. In spite of everything, we will try to keep the United States in a state of neutrality. However, in the event of failure, we will offer Mexico: to wage war together and to make peace together. For our part, we will provide Mexico with financial assistance and assure that at the end of the war she will receive back the territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona that she lost. We entrust you to work out the details of this agreement. You will immediately and top-secretly warn President Carranza as soon as the declaration of war between us and the United States becomes a fact. Add that the president of Mexico can, on his own initiative, inform the Japanese ambassador that it would be very beneficial for Japan to join our union immediately. Pay the president’s attention to the fact that we will continue to make full use of our submarine forces, which will force England to sign the world in the coming months.

Story completion

The German command began to adjust its ciphers only from 1916, changing codes every month (and later even daily). But the principle of encryption remained the same. And by this time, specialists from Room 40 had already become completely familiar with the German encryption system, speeding up the process of decrypting a message. Sometimes the content of German radiograms in London was recognized before their addressee.

Old Admiralty

In 1919, Room 40 was disbanded and on its base, as well as on the basis of the cryptographic intelligence unit of the British Army MI1b (Eng. Military Intelligence, Section 1), the Government School of Coding and Encryption (GC & CS) was formed. During World War II, this school was located in Bletchley Park and subsequently became an electronic intelligence service independent of military intelligence. In 1946, it was renamed the Center for Government Communications (Eng. Government Communications Headquarters, GCHQ), and from 1951 to 1952 it was moved to Cheltenham. But the actual room 40 is still located on the first floor of the Whitehall Admiralty Building in London.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/394877/

All Articles