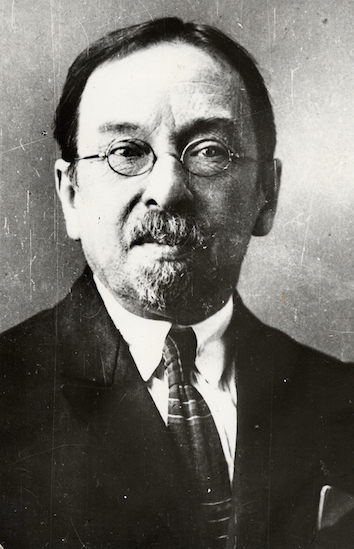

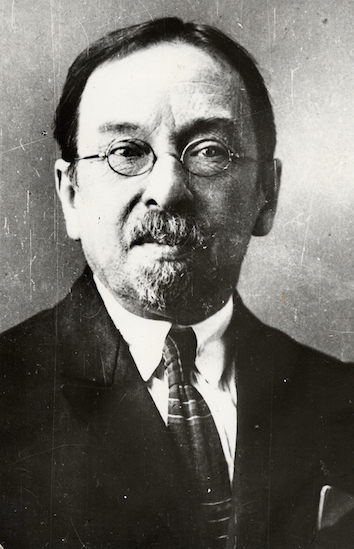

"Thinking machine" Shchukarev

Logical machines are an important stage in the development of modern computers. Their story begins in the XIII century with the work of the medieval philosopher and thinker Raymond Lullius (Raymundus Lullius), recognized as a reformer of logic. He wrote the book "Great Art" ("Ars magna") describing the theory of combining concepts. Logic machines reached their peak at the end of the 19th century thanks to the work of the Englishman William Stanley Jevons (1835–82), American Allan Marquand (1853–1924) and, somewhat later, the Russian inventors Pavel Dmitrievich Khrushchov (1849-1909) and Alexander Nikolaevich Shchukarev (1864-1936).

In the spring of 1914, at a lecture on “Knowledge and Thinking”, which was held at the Moscow Polytechnic Museum, Alexander Nikolaevich Schukarev, a professor of chemistry at the Kharkov Technological Institute, demonstrated the “logical thinking machine” to those present. This mechanical device is able to make simple logical conclusions from the given premises. The invention has caused a lot of controversy, because according to the scientists of the time, technology was not allowed to think ...

But first of all the story of the life of the developer himself - a talented professor Shchukarev.

')

Alexander Nikolaevich Shchukarev was born in November 1864 in Moscow. Abilities to mathematics and physics appeared in his childhood. After graduating from high school in 1885, he immediately entered Moscow University in the department of natural sciences of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics. After graduation, Shchukarev began working as a laboratory assistant in one of the first thermochemical laboratories of Professor Vladimir Fedorovich Lungin, where he conducted his research for seventeen years. He had very diverse scientific interests and besides chemistry, the scientist studied the logic, methodology of science, as well as the problems of mechanization of the formalized aspects of thinking.

In 1906, Shchukarev defended his master's thesis on the topic “Investigations of the internal energy of gaseous and liquid bodies”, after which he received the position of privat-docent at Moscow University. Four years later, he already defended his doctoral thesis entitled “Properties of Solutions at a Critical Displacement Temperature”.

In 1909, Alexander Nikolaevich improved the slide rule, which at that time was the main mathematical tool for most scientific and technical calculations. A year later, he became an extraordinary professor in the department of general chemistry at the Higher Mining School in Yekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk), where he discovered and described the phenomenon of chemical polarization and the magnetochemical effect.

In fact, in April 1914, Shchukarev presented his invention - the “machine of logical thinking”, which carried out simple logical conclusions based on the initial semantic premises. The scientist improved the device created by the English mathematician VS Jevons called the "logical piano" (1870). The logic machine of Shchukarev was smaller and consisted entirely of metal, and also technically proved to be more perfect.

Young Schukarev

From 1926 to 1931 at the Kharkov Institute of Technology (KTI) Shchukarev headed the department of physical chemistry. He worked in this position for about 20 years and even being a retired, continued to advise many research institutes (Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chamber of Weights and Measures, Institute of Experimental Medicine, etc.).

Alexander Nikolaevich was ardently devoted to science and never betrayed his principles and ideals. Even in the most difficult post-revolutionary years, he steadfastly defended his views. Schukarev remained aloof from politics and as a master of his craft, he accepted the thesis “where the struggle begins, there the creativity ends.”

One curious episode can give a more colorful idea of what kind of person it was. In 1919, after the establishment of Soviet power in Kharkov, Alexander Nikolayevich had to speak at the first meeting of the “Circle for the Study of Dialectical Materialism”. He read a scientific report and as soon as he finished, suddenly recollecting himself, he added: “Oh yes, I forgot that this is a circle for the study of dialectical materialism ... What can be said about the study of dialectical materialism? Just that you can do anything is the same, for example, collecting white mice. ” After this, Shchukarev calmly left, and the scandal that arose was somehow hushed up.

Alexander Nikolaevich was described as a typical professor with the classic habits of a true intellectual who lives only in science and does not notice anything around. He lived in his apartment, wore a coat, and always looked neat. Achievements and achievements of this man evoked universal respect, perhaps because of this he managed to avoid repression. Schukarev ended his life as a respectable and important professor. In November 1935, an eminent scientist became seriously ill and died five months later.

The history of the “Thinking Machine” begins in 1911, when Shchukarev accepted an invitation to work at the Kharkov Institute of Technology (KTI) at the Department of General and Inorganic Chemistry. Alexander Nikolayevich had a predecessor - KhTIv Khrushchov, a professor at the KhTI, who had studied the question of the mechanization of thinking and the methodology of science before him. Using the ideas of the English mathematician V.S. Jevons, Khrushchev built his own "logical piano".

Pavel Dmitrievich Khrushchev

This device fell into the hands of Shchukarev after the death of Khrushchov and attracted the attention of the first, as a technical means of mechanizing the formalized aspects of thinking. Since then, the scientist seriously carried away by improving the "machine of logical thinking." Being engaged in teaching activities together with research in the field of physical chemistry, he found time to develop the ideas of Jevons. As a result of his works, the “logical piano” was transformed; a light screen appeared in it, which can be considered the prototype of modern displays.

The logical machine of Khrushchov

Here is what Schukarev wrote about his work:

"The machine of logical thinking"

Schukarev modernized the “logical thinking machine” and presented it at a meeting of the Society of Physical and Chemical Sciences at Kharkov University in 1912. After that, the device was presented in several cities of the Russian Empire and finally in 1914 appeared before the Moscow scientific community. The demonstration was held in the Polytechnic Museum at the lecture "Knowledge and thinking." The car looked like a box with a height of 40 cm, a width of 5 cm and a length of 25 cm. It was equipped with a keyboard, the back row was subject, the front row was predicate. Inside, there were 16 rods (sticks) with a font at the back, each with 4 letters ABC and D. The rods began to move when you clicked the buttons on the input data input panel (meaning messages). In turn, the rods worked on the light panel, where the final result appeared in the form of words (logical conclusions from the given semantic premises).

During the presentation, Shchukarev tried to show his device to the public in the most detailed, complete and multifaceted way. For clarity, he asked the machine confusing logical puzzles, the "clumsiness" of the filing of which did not confuse the device at all. Below is an example of one of the tasks.

The initial premises were asked: “silver is metal; metals are conductors; conductors have free electrons; free electrons create a current under the action of an electric field. " The car received the following conclusions:

- not silver, but metal (for example, copper) is a conductor, it has free electrons, which under the action of an electric field create a current;

- not silver, not metal, but a conductor (for example, carbon), has free electrons that create a current under the action of an electric field;

- not silver, not metal, not a conductor (for example, sulfur) does not have free electrons and does not conduct electric current.

By the principle, if A = AB and B = BC, then A = ABC or if A = 1 / p B 2, and B = 1 / t C 3, then A = 1 / p 1 / t C.

An even more simple example is the creation of interesting conclusions from the premises: “the thief had a white hat and black hair” and “Karp had a white hat and black hair”. It turned out: “Karp had a white hat and black hair and he is a thief”, but further conclusions followed: “Karp who has both is not a thief” and “a thief who has both is not Karp”.

As mentioned above, the emergence of a “thinking machine” has caused a lot of heated debate in the scientific world. Two different camps were formed - some considered the invention a real breakthrough in science, others were convinced that all this was just tricks and tricks, because the process of logical thinking is not amenable to mechanization.

A plaque mounted on the gable of the building of the Chemical building of NTU "KPI"

Different professors expressed their opinions. For example, A.N. Sokov took the development of his colleague very, very positively. He drew parallels between arithmometers that knew how to add, subtract, multiply millions of numbers by turning a lever with a logical machine that yields logical conclusions with the help of keystrokes.

But Professor I.E. Orlov. In one of the leading ideological publications "Under the banner of Marxism", he criticized not only the "thinking machine", but also all the scientific activities of Schukarev. The article was titled “On the Rationalization of Intellectual Labor.” Orlov marked the presentation of the car as a comical performance, showing Jevons's school allowance as a “thinking” apparatus. The critic laughed at the naivety of the listeners who believed that thinking was formal and could be mechanized.

But unfortunately, it was precisely Orlov’s negative opinion that became prevalent in scientific circles. As a result, they began to call the “machine of logical thinking” unscientific, gradually losing any interest in it. In the late 20s, Shchukarev stopped public demonstrations of his logical machine and transferred the model for storage to the mathematics department at Kharkov University.

And only almost 40 years later, scientists again returned to the study of whether the machine is able to think. The reason for this was the study of the famous English mathematician Alan Mathison Turing (Alan Mathison Turing), who published the work “Can a car think?” .

Alan Matheson Turing (1912-1954)

As for Schukarev's “machine of logical thinking”, the fate of this device is lost in the tragic events of the subsequent wars - the First World and Civil Wars.

Alexander Nikolaevich Shchukarev has done quite a lot for modern science. Together with Professor Luginin, he founded modern thermochemistry, discovered the polarization current during a chemical reaction and the magnetochemical effect in electrochemistry, revealed the effect of deformation of the crystal lattice of metals and the effect of ultraviolet and X-ray irradiation on metals.

One of the works of Shchukarev - "Problems of the theory of knowledge . "

Directly to Alexander Nikolaevich belongs the derivation of the nominal equation of the dissolution kinetics of crystals, which has become classical, is given in modern textbooks of physical chemistry and is widely used in research. His idea of philosophical structuralism, described in the work "Essays on the Philosophy of Natural Science", which is mainly based on the assumption of the orderliness of the world, was one of the first in the philosophy of science.

In the spring of 1914, at a lecture on “Knowledge and Thinking”, which was held at the Moscow Polytechnic Museum, Alexander Nikolaevich Schukarev, a professor of chemistry at the Kharkov Technological Institute, demonstrated the “logical thinking machine” to those present. This mechanical device is able to make simple logical conclusions from the given premises. The invention has caused a lot of controversy, because according to the scientists of the time, technology was not allowed to think ...

But first of all the story of the life of the developer himself - a talented professor Shchukarev.

')

short biography

Alexander Nikolaevich Shchukarev was born in November 1864 in Moscow. Abilities to mathematics and physics appeared in his childhood. After graduating from high school in 1885, he immediately entered Moscow University in the department of natural sciences of the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics. After graduation, Shchukarev began working as a laboratory assistant in one of the first thermochemical laboratories of Professor Vladimir Fedorovich Lungin, where he conducted his research for seventeen years. He had very diverse scientific interests and besides chemistry, the scientist studied the logic, methodology of science, as well as the problems of mechanization of the formalized aspects of thinking.

In 1906, Shchukarev defended his master's thesis on the topic “Investigations of the internal energy of gaseous and liquid bodies”, after which he received the position of privat-docent at Moscow University. Four years later, he already defended his doctoral thesis entitled “Properties of Solutions at a Critical Displacement Temperature”.

In 1909, Alexander Nikolaevich improved the slide rule, which at that time was the main mathematical tool for most scientific and technical calculations. A year later, he became an extraordinary professor in the department of general chemistry at the Higher Mining School in Yekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk), where he discovered and described the phenomenon of chemical polarization and the magnetochemical effect.

In fact, in April 1914, Shchukarev presented his invention - the “machine of logical thinking”, which carried out simple logical conclusions based on the initial semantic premises. The scientist improved the device created by the English mathematician VS Jevons called the "logical piano" (1870). The logic machine of Shchukarev was smaller and consisted entirely of metal, and also technically proved to be more perfect.

Young Schukarev

From 1926 to 1931 at the Kharkov Institute of Technology (KTI) Shchukarev headed the department of physical chemistry. He worked in this position for about 20 years and even being a retired, continued to advise many research institutes (Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chamber of Weights and Measures, Institute of Experimental Medicine, etc.).

Alexander Nikolaevich was ardently devoted to science and never betrayed his principles and ideals. Even in the most difficult post-revolutionary years, he steadfastly defended his views. Schukarev remained aloof from politics and as a master of his craft, he accepted the thesis “where the struggle begins, there the creativity ends.”

One curious episode can give a more colorful idea of what kind of person it was. In 1919, after the establishment of Soviet power in Kharkov, Alexander Nikolayevich had to speak at the first meeting of the “Circle for the Study of Dialectical Materialism”. He read a scientific report and as soon as he finished, suddenly recollecting himself, he added: “Oh yes, I forgot that this is a circle for the study of dialectical materialism ... What can be said about the study of dialectical materialism? Just that you can do anything is the same, for example, collecting white mice. ” After this, Shchukarev calmly left, and the scandal that arose was somehow hushed up.

Alexander Nikolaevich was described as a typical professor with the classic habits of a true intellectual who lives only in science and does not notice anything around. He lived in his apartment, wore a coat, and always looked neat. Achievements and achievements of this man evoked universal respect, perhaps because of this he managed to avoid repression. Schukarev ended his life as a respectable and important professor. In November 1935, an eminent scientist became seriously ill and died five months later.

The history of the thinking machine

The history of the “Thinking Machine” begins in 1911, when Shchukarev accepted an invitation to work at the Kharkov Institute of Technology (KTI) at the Department of General and Inorganic Chemistry. Alexander Nikolayevich had a predecessor - KhTIv Khrushchov, a professor at the KhTI, who had studied the question of the mechanization of thinking and the methodology of science before him. Using the ideas of the English mathematician V.S. Jevons, Khrushchev built his own "logical piano".

Pavel Dmitrievich Khrushchev

This device fell into the hands of Shchukarev after the death of Khrushchov and attracted the attention of the first, as a technical means of mechanizing the formalized aspects of thinking. Since then, the scientist seriously carried away by improving the "machine of logical thinking." Being engaged in teaching activities together with research in the field of physical chemistry, he found time to develop the ideas of Jevons. As a result of his works, the “logical piano” was transformed; a light screen appeared in it, which can be considered the prototype of modern displays.

The logical machine of Khrushchov

Here is what Schukarev wrote about his work:

I tried to build a somewhat modified specimen, introducing some improvements to Jevons' design. These improvements, however, were not of a fundamental nature. I just gave the instrument a slightly smaller size, made it entirely out of metal and eliminated some structural defects, which, I must admit, in the Jevons device, it was pretty decent. Some further step forward was the addition of a special light screen to the instrument, to which the work of the machine is transmitted and on which the results of “thinking” do not appear in letter-like form, as on Jevons’s machine itself, but in ordinary verbal form.

"The machine of logical thinking"

Schukarev modernized the “logical thinking machine” and presented it at a meeting of the Society of Physical and Chemical Sciences at Kharkov University in 1912. After that, the device was presented in several cities of the Russian Empire and finally in 1914 appeared before the Moscow scientific community. The demonstration was held in the Polytechnic Museum at the lecture "Knowledge and thinking." The car looked like a box with a height of 40 cm, a width of 5 cm and a length of 25 cm. It was equipped with a keyboard, the back row was subject, the front row was predicate. Inside, there were 16 rods (sticks) with a font at the back, each with 4 letters ABC and D. The rods began to move when you clicked the buttons on the input data input panel (meaning messages). In turn, the rods worked on the light panel, where the final result appeared in the form of words (logical conclusions from the given semantic premises).

During the presentation, Shchukarev tried to show his device to the public in the most detailed, complete and multifaceted way. For clarity, he asked the machine confusing logical puzzles, the "clumsiness" of the filing of which did not confuse the device at all. Below is an example of one of the tasks.

The initial premises were asked: “silver is metal; metals are conductors; conductors have free electrons; free electrons create a current under the action of an electric field. " The car received the following conclusions:

- not silver, but metal (for example, copper) is a conductor, it has free electrons, which under the action of an electric field create a current;

- not silver, not metal, but a conductor (for example, carbon), has free electrons that create a current under the action of an electric field;

- not silver, not metal, not a conductor (for example, sulfur) does not have free electrons and does not conduct electric current.

By the principle, if A = AB and B = BC, then A = ABC or if A = 1 / p B 2, and B = 1 / t C 3, then A = 1 / p 1 / t C.

An even more simple example is the creation of interesting conclusions from the premises: “the thief had a white hat and black hair” and “Karp had a white hat and black hair”. It turned out: “Karp had a white hat and black hair and he is a thief”, but further conclusions followed: “Karp who has both is not a thief” and “a thief who has both is not Karp”.

"Can a car think?"

As mentioned above, the emergence of a “thinking machine” has caused a lot of heated debate in the scientific world. Two different camps were formed - some considered the invention a real breakthrough in science, others were convinced that all this was just tricks and tricks, because the process of logical thinking is not amenable to mechanization.

A plaque mounted on the gable of the building of the Chemical building of NTU "KPI"

Different professors expressed their opinions. For example, A.N. Sokov took the development of his colleague very, very positively. He drew parallels between arithmometers that knew how to add, subtract, multiply millions of numbers by turning a lever with a logical machine that yields logical conclusions with the help of keystrokes.

But Professor I.E. Orlov. In one of the leading ideological publications "Under the banner of Marxism", he criticized not only the "thinking machine", but also all the scientific activities of Schukarev. The article was titled “On the Rationalization of Intellectual Labor.” Orlov marked the presentation of the car as a comical performance, showing Jevons's school allowance as a “thinking” apparatus. The critic laughed at the naivety of the listeners who believed that thinking was formal and could be mechanized.

But unfortunately, it was precisely Orlov’s negative opinion that became prevalent in scientific circles. As a result, they began to call the “machine of logical thinking” unscientific, gradually losing any interest in it. In the late 20s, Shchukarev stopped public demonstrations of his logical machine and transferred the model for storage to the mathematics department at Kharkov University.

And only almost 40 years later, scientists again returned to the study of whether the machine is able to think. The reason for this was the study of the famous English mathematician Alan Mathison Turing (Alan Mathison Turing), who published the work “Can a car think?” .

Alan Matheson Turing (1912-1954)

As for Schukarev's “machine of logical thinking”, the fate of this device is lost in the tragic events of the subsequent wars - the First World and Civil Wars.

Alexander Nikolaevich Shchukarev has done quite a lot for modern science. Together with Professor Luginin, he founded modern thermochemistry, discovered the polarization current during a chemical reaction and the magnetochemical effect in electrochemistry, revealed the effect of deformation of the crystal lattice of metals and the effect of ultraviolet and X-ray irradiation on metals.

One of the works of Shchukarev - "Problems of the theory of knowledge . "

Directly to Alexander Nikolaevich belongs the derivation of the nominal equation of the dissolution kinetics of crystals, which has become classical, is given in modern textbooks of physical chemistry and is widely used in research. His idea of philosophical structuralism, described in the work "Essays on the Philosophy of Natural Science", which is mainly based on the assumption of the orderliness of the world, was one of the first in the philosophy of science.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/393773/

All Articles