Animals and children can count without language and symbols.

People think that babies absorb information like a sponge, but they do not analyze the world around them. The study of the neuroscientist Elizabeth Brannon refutes this opinion - both monkeys and small children have abstract thinking. They can think without knowing what a “figure” is and without understanding the language.

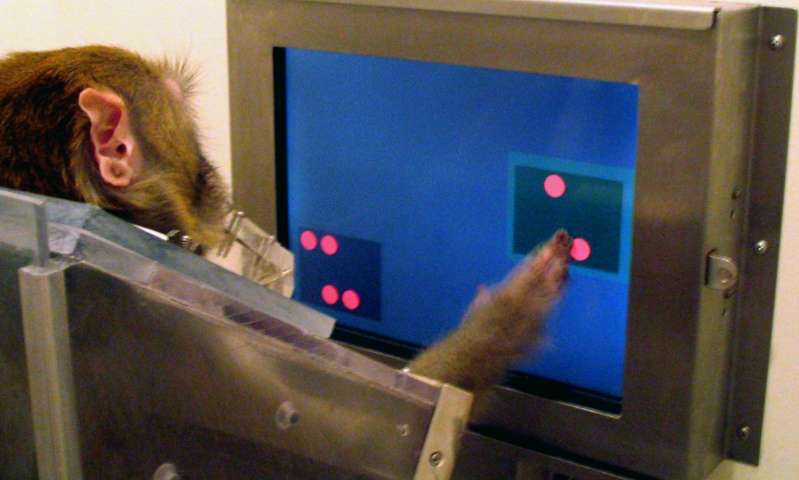

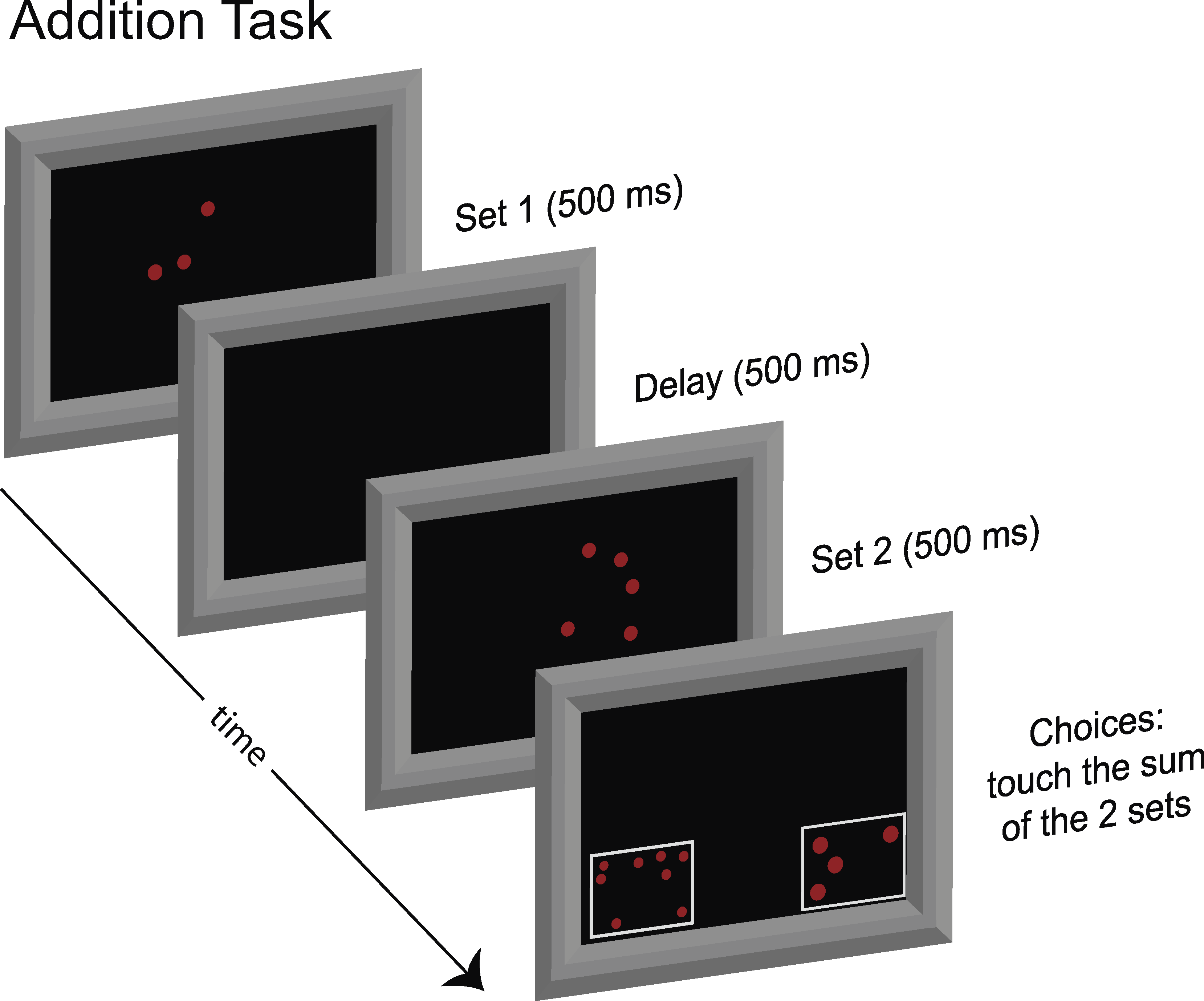

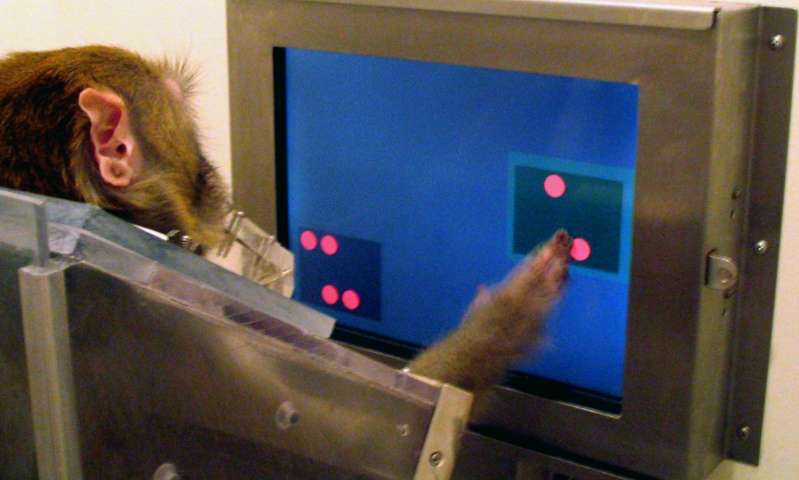

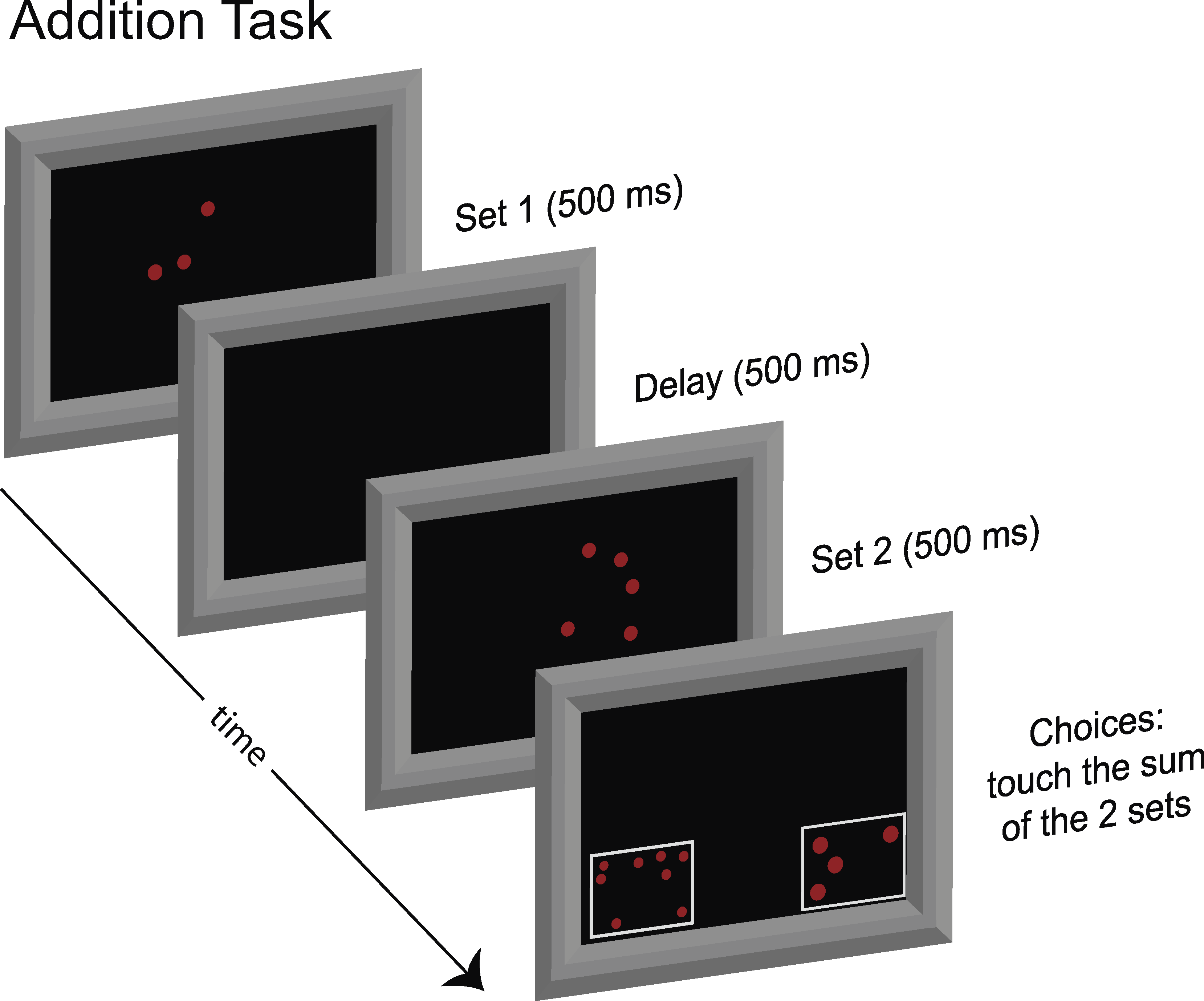

For twenty years, Elizabeth Brannon and her colleagues have been studying the abilities of rhesus monkeys in mathematics. These primates are not only able to distinguish between “more” and “less”, but are also able to determine addition and subtraction. Monkeys were taught to solve problems with dots on the screen - for the right choice they get juice as a reward.

Scientists have found that monkeys distribute sets of points in ascending and descending order, and understand when sets of points have been folded or subtracted. Moreover, the monkeys memorize the number of tones heard and can choose a set from the number of points, which coincides with the number of notes in the melody.

')

Example of a task: a monkey must choose the sum of the points shown before.

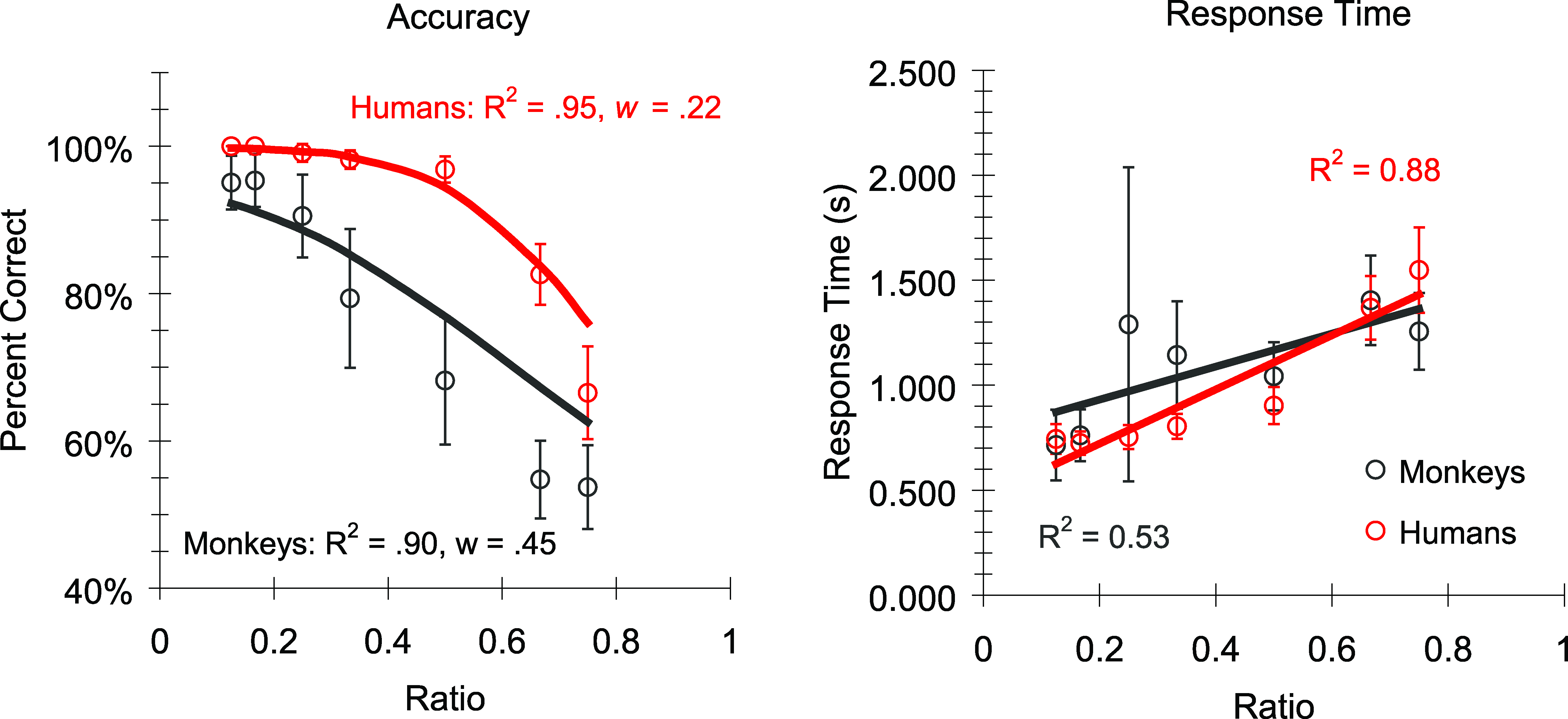

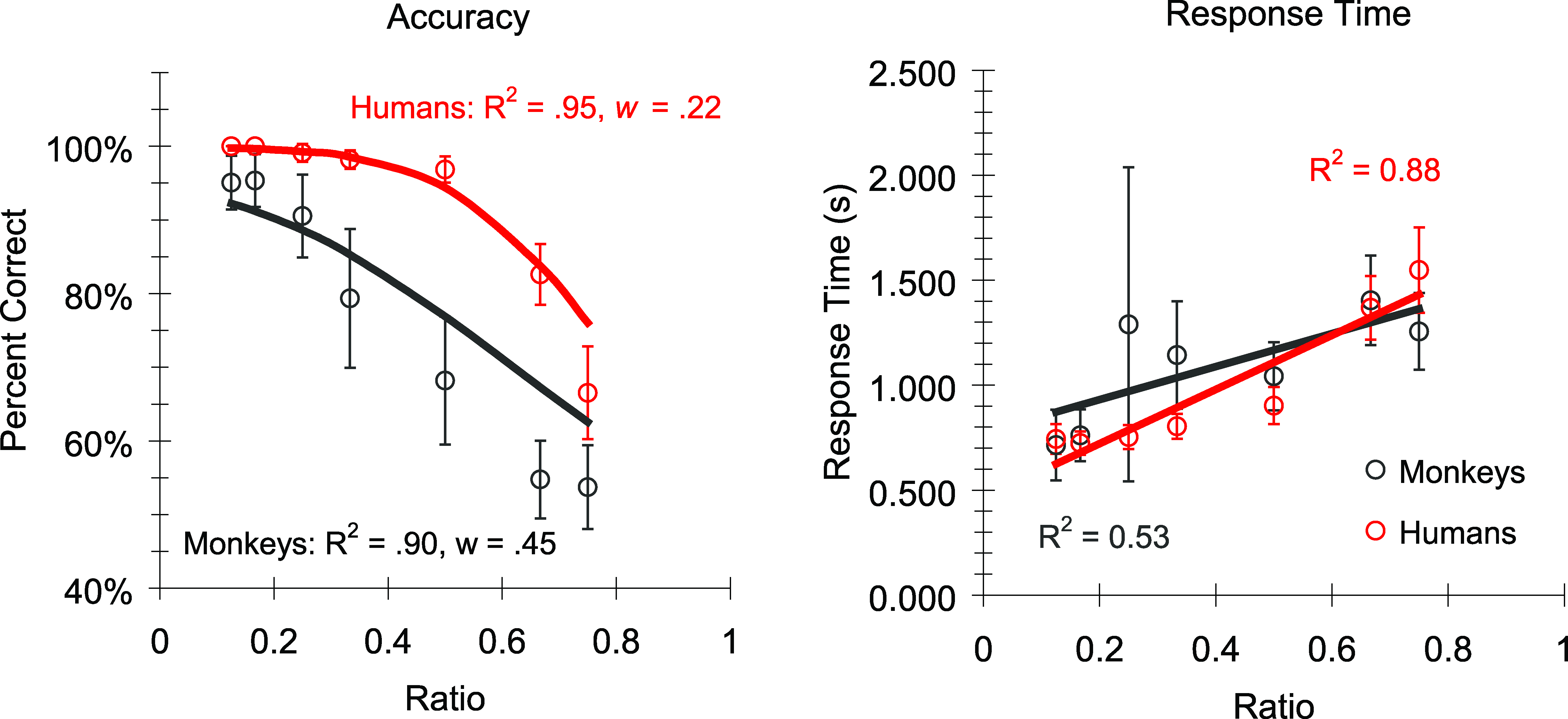

Monkeys compared with ordinary students. Students can properly solve complex problems, but monkeys with simple tasks cope a little faster - perhaps because the macaques had a stimulus in the form of juice, and the students were not fed.

As in the case of humans, monkeys show the best result when comparing small groups of points - it is easier for them to understand that six are more than four than twelve are more than ten. “We observe the same process in monkeys by the same rules as in humans, both in adults and in children,” comments Brannon. In her opinion, this proves that it is not abstract thinking that distinguishes man from animals.

Small children are able to see the difference in the number of objects before they learn to count. Researchers showed the baby several sets of six points in different configurations on the screen, while the baby didn’t get bored - he got used to this number of points. If, after changing the image, the child began to look at the screen for a long time, it means that he noticed the difference - for example, between the new twelve points and the previous six.

It turns out that symbols and language are not always needed to understand math. The study provides a more complete picture of what scientists call an "approximate system of calculation." Although a two-year-old child cannot always count eight candies, he is able to estimate that eight candies are more than three. For example, crows use the same system - they are also able to count .

For twenty years, Elizabeth Brannon and her colleagues have been studying the abilities of rhesus monkeys in mathematics. These primates are not only able to distinguish between “more” and “less”, but are also able to determine addition and subtraction. Monkeys were taught to solve problems with dots on the screen - for the right choice they get juice as a reward.

Scientists have found that monkeys distribute sets of points in ascending and descending order, and understand when sets of points have been folded or subtracted. Moreover, the monkeys memorize the number of tones heard and can choose a set from the number of points, which coincides with the number of notes in the melody.

')

Example of a task: a monkey must choose the sum of the points shown before.

Monkeys compared with ordinary students. Students can properly solve complex problems, but monkeys with simple tasks cope a little faster - perhaps because the macaques had a stimulus in the form of juice, and the students were not fed.

As in the case of humans, monkeys show the best result when comparing small groups of points - it is easier for them to understand that six are more than four than twelve are more than ten. “We observe the same process in monkeys by the same rules as in humans, both in adults and in children,” comments Brannon. In her opinion, this proves that it is not abstract thinking that distinguishes man from animals.

Small children are able to see the difference in the number of objects before they learn to count. Researchers showed the baby several sets of six points in different configurations on the screen, while the baby didn’t get bored - he got used to this number of points. If, after changing the image, the child began to look at the screen for a long time, it means that he noticed the difference - for example, between the new twelve points and the previous six.

It turns out that symbols and language are not always needed to understand math. The study provides a more complete picture of what scientists call an "approximate system of calculation." Although a two-year-old child cannot always count eight candies, he is able to estimate that eight candies are more than three. For example, crows use the same system - they are also able to count .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/393427/

All Articles