When the USAF realized a flaw with average numbers

Excerpt from Todd Rose's The End of Average

In the early 1950s, Americans measured the bodies of more than 4,000 pilots, according to 140 characteristics, to design the perfect cockpit for the average pilot.

In the late 1940s, the US Air Force had a serious problem: the pilots lost control of the aircraft. Then came the era of jet engines, so that the aircraft became faster and more difficult to manage. But catastrophes happened so often and on so many different planes that the USAF faced the real problem of saving lives. At worst, up to 17 pilots were broken in a day.

For such non-combat accidents, there were two official designations: accidents ( incidents ) and accidents, and they ranged from an unintended dive and a bad landing to fatal accidents and the destruction of an aircraft. At first, the aviation authorities dumped the blame on people in the cockpits, calling the "pilot error" the main reason in the accident reports. Such an assessment seemed reasonable, since in the aircraft themselves technical failures were rare. Engineers confirmed this again and again, testing mechanics and electronics, where they did not find any defects. The pilots were also confused. One thing they knew for sure: that their piloting abilities are not the cause. If this is not a human or mechanical error, then what is it?

')

After numerous investigations without answers, officials paid attention to the design of the cabin itself. Back in 1926, when the army designed the very first cockpit, the engineers measured the physical parameters of hundreds of male pilots (no one seriously considered the possibility of controlling the aircraft of a woman), and used this data to standardize the size of the cockpit. Over the next three decades, the size and shape of the chair, the distance to the pedals and the steering wheel, the height of the windscreen, and even the shape of the helmet corresponded to the average parameters of a 1926 pilot.

Now, military engineers began to wonder if the pilots had grown since 1926. To get the new values of the physical parameters of the pilots, the air force initiated the largest research pilots ever conducted. In 1950, more than 4,000 pilots were measured by 140 size parameters at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, including the length of the thumb, the height of the perineum, and the distance from the eye to the ear. As a result, they calculated the average value of each parameter. Everyone believed that a more thorough calculation of the parameters of the average pilot would lead to the creation of a more comfortable cockpit and reduce the number of accidents. Or almost everything. One 23-year-old scientist who recently entered the service had doubts.

Lieutenant Gilbert S. Daniels did not look like a typical character of air battles boiling from testosterone. He was thin and wore glasses. He liked flowers and landscape design, and in high school, Gilbert headed the botanical garden club. Before being distributed to the aeromedical laboratory at Wright-Patterson air base right after the university, he never flew an airplane. But that didn't matter. As a novice researcher, he was assigned to measure the limbs of the pilots with the help of a tape measure.

For Gilbert, this was not the first time. Aeromedical Laboratory took it, because at Harvard the student specialized in physical anthropology, which studied the anatomy of people. In the first half of the 20th century, this area of science largely focused on the classification of human personalities by types of groups according to their average body shape - a practice known as “typing”. For example, many physical anthropologists believed that a low and heavy figure corresponds to funny and funny people, and high hairline and plump lips reflect a "criminal personality type."

However, Daniels was not interested in typing. Instead, his thesis contained a rather laborious and painstaking comparison of the shape of the hands of 250 Harvard male students. All students were similar in ethnic and socio-cultural status (that is, white and rich), but unexpectedly for anthropologists there was no similarity in their hands at all. Even more surprising, Daniels discovered, the average hand didn’t match any of the individual measurements! There was no such thing as a medium sized hand. “When I left Harvard, it was clear to me that for designing something for a particular human being, the average parameters were completely useless,” Daniels told me.

So when the army landed the young Gilbert to measure the pilots, he held a secret belief about the average size, which contradicted almost a century of the military design philosophy. Sitting in the aeromedical laboratory, measuring his arms, legs, waist and foreheads, he continued to ask himself the same question: How many pilots really have an average size?

Gilbert decided to find out. Using data from 4063 pilots, Daniels calculated the average of 10 physical characteristics that were considered most important for design, including height, chest circumference and sleeve length. So he got the dimensions of the "average pilot", which the researcher considered such, whose parameters are in the average 30% of the range of values for each parameter. So, for example, when, after the calculation, an exact average height of 175 cm was obtained, Daniels determined a height of 170 to 180 cm for the “average pilot”. Then he carefully, one by one, compared each individual pilot with average values.

Up to this point, the generally accepted opinion among fellow researchers from the Air Force was that the absolute majority of pilots would fit into the average range for most parameters. In the end, the pilots initially underwent a preliminary selection in order to meet the average parameters. (For example, if your height is 200 cm, then you will never be taken as a pilot in the first place). Scientists assumed that a significant number of pilots would correspond to the average range in all 10 parameters. But Gilbert Daniels was amazed when he determined the true number of such pilots.

Zero.

Of the 4063 pilots, not one person corresponded to the average range in all 10 parameters. One had arms longer than average and legs shorter than average, the other could have a wide chest, but small hips. What is even more striking is that Daniels found out that if you take just three out of ten size parameters - for example, neck circumference, hip circumference and wrist circumference - less than 3.5% of the pilots corresponded to the average parameters for all three indicators. Daniel's conclusions were clear and irrefutable. there was no such thing as an average pilot . If you design the cockpit for the average pilot, then in reality it will not be suitable for anyone.

Daniels revelation was so significant that it could end the era of basic assumptions about individual features and start a new era. But even the most important ideas require proper interpretation. We like to think that the facts speak for themselves, but in reality this is not so. After all, Gilbert Daniels was not the first to discover the absence of an average person.

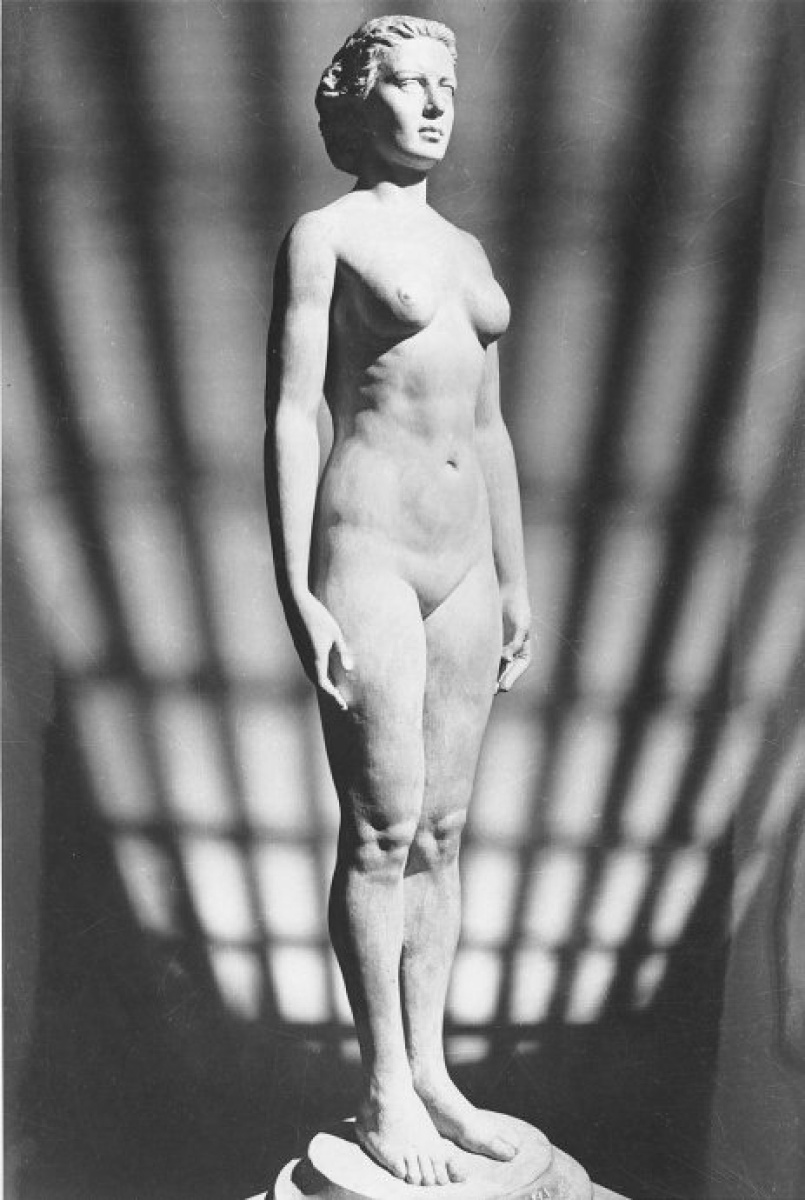

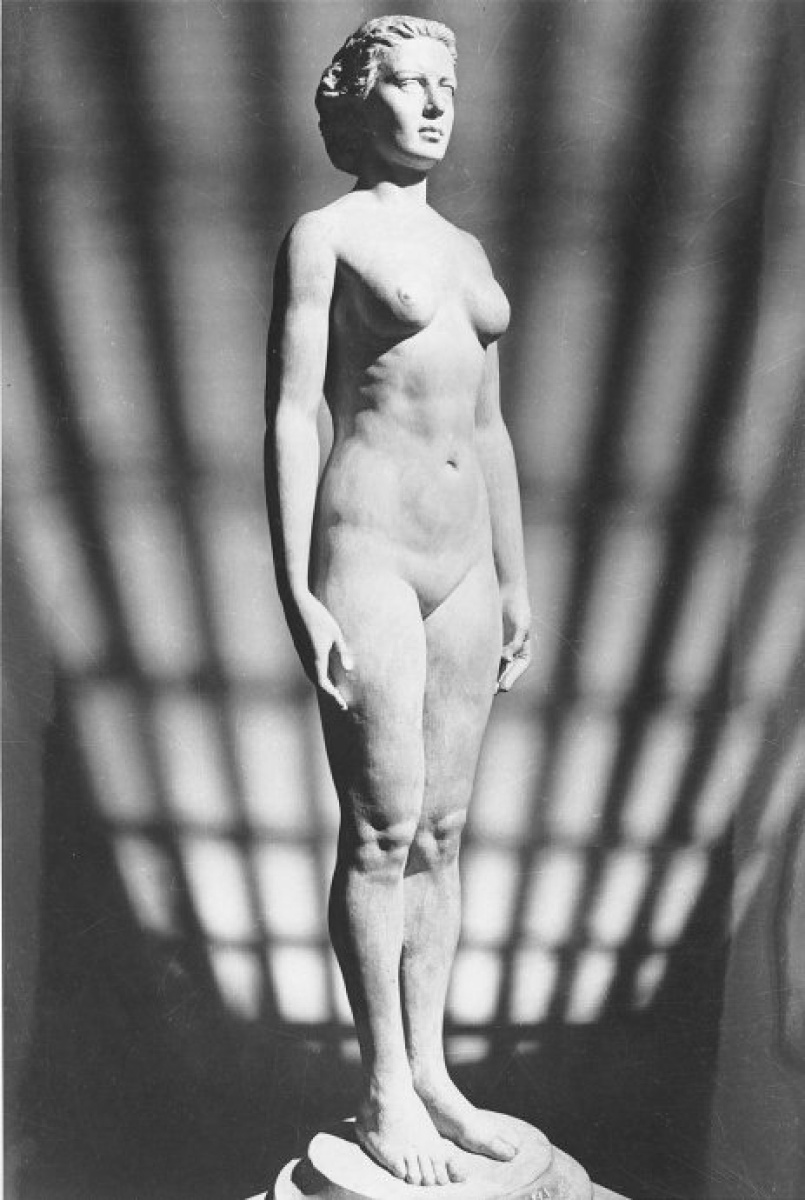

The norm was designed to demonstrate “ideal” female forms as measured by 15,000 young adult women. The statue was installed in the Cleveland Medical Museum, created by a gynecologist Dr. Robert L. Dickinson (Robert L. Dickinson) and his assistant, Abram Belskie

Seven years earlier, the Cleveland newspaper Plain Dealer announced a competition for illustration for the front page, and the Cleveland Medical Museum, the Cleveland Medical Academy, the medical school, and the Cleveland Education Council also sponsored. The winners of the contest were promised military bonds for $ 100, $ 50 and $ 25, and ten more lucky girls could qualify for military brands with a face value of $ 10. Competition? The girls were asked to send the parameters of their bodies, which are closest to the parameters of a typical woman, Norma, which is immortalized in a statue from the Cleveland Medical Museum.

Norma was the creation of the famous gynecologist Robert L. Dickinson and his assistant Abram Belsky, who made a figure by measuring 15,000 young adult women. Dr. Dickinson was an influential figure for his time: Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Brooklyn Hospital, President of the American Society of Gynecologists and Chairman of Obstetrics at the American Medical Association. He was also an artist - Rodin from obstetrics, as one colleague called him - and his entire career made sketches of women, their various shapes and sizes, studying the relationship of body types and behavior.

Like many scientists of those days, Dickinson believed that the truth can be determined by collecting and averaging a large amount of data. "Norm" personifies such a truth. For Dickinson, the collection of thousands of indicators of the size of the female body and the calculation of the average value provided an insight into a typical female physique — someone normal.

Simultaneously with the display of the statue, the Cleveland Medical Museum began selling miniature reproductions of Norma, advertising her as the “Perfect Girl,” giving a start to the real mania around Norma. One well-known physical anthropologist said that Norma's physique is "a kind of perfection of bodily form," the artists proclaimed her beauty as a "great standard", and physical education teachers showed her as a demonstration of how a young girl should look. They prescribed to perform individual exercises based on the specific differences of the individual student from the ideal. Norma was printed in Time magazine , she was in newspaper cartoons, and in the documentary series on CBS ( This American Look ) her parameters were read out loud so that every girl could check that she had a normal body too.

On November 23, 1945, Cleveland Plain Dealer announced the winner: a slender brunette, a theater teller named Martha Skidmore. The newspaper wrote that Skidmore loves to dance, swim and play bowling - in other words, her tastes are just as normal as her figure, which was considered the ideal of female forms.

Before the competition, the judges assumed that the parameters of the majority of the contestants would be quite close to the average, and that millimeters would have to be considered to determine the winner. In reality, nothing like this was close. Less than 40 out of 3,864 contestants fell into an average size of just 5 out of 9 parameters, and not a single contestant — not even Martha Skidmore — was close to the average for all 9 parameters. Just as Daniels’s study determined the absence of such a notion as an average pilot, the competition for the role of Norma showed that an average woman does not exist either.

But although Daniels and the contest organizers got the same result, they made completely different conclusions from this. Most doctors and scientists of that time did not consider at all that Norma was the wrong ideal. Quite the contrary: they concluded that most American women are unwell and do not maintain their normal form. One of these was Dr. Bruno Gebhard, director of the Cleveland Medical Museum: he lamented that post-war women were largely unsuitable for military service, and reproached them by mentioning poor fitness, making them “poor producers and poor consumers ".

Daniels’s interpretation was exactly the opposite. “The tendency to think in terms of the" average man "is a trap that many lead to miscalculations," he wrote in 1952. “It’s almost impossible to find an average pilot not because of some individual features of his group, but because of the large variation in body size of all people.”

Instead of suggesting pilots to make efforts to comply with the artificial ideal of normality, Daniels analysis led him to a conclusion that seemed to contradict common sense and is the cornerstone of his book: any system designed for the average person is doomed to failure . ”

Daniels published his results in 1952 in a technical note of the Air Force called The "Average Man"? In it, he argued that if the army wants to improve the effectiveness of its soldiers, including pilots, it must change the design of any environment in which soldiers are supposed to work. Radical changes are recommended: the environment should correspond to individual parameters, not the average.

Surprisingly, to the honor of the air force, they listened to the arguments of the scientist. “The old designs of the Air Force were all based on a search for pilots similar to the average pilot,” Daniels explained to me. “But when we showed them that the average pilot was a useless concept, they found the strength to focus on designing the cockpits individually for each pilot. That's when the situation began to change for the better. "

Rejecting the orientation on average values, the Air Force initiated a revolution in the philosophy of military design, based on the main principle: individual adjustment. Instead of fitting a person to the norms of the system, the army began to customize the system for an individual. Immediately, the United States Air Force made new demands that the cockpits fit all pilots whose dimensions fall within the range of distribution between 5% and 95% for each characteristic.

When the aircraft manufacturers learned about the new requirements, they started abutting, insisting that the changes would cost too much and take years to solve the related engineering problems. But the military refused to compromise, and then - to everyone's surprise - aviation engineers very quickly offered rather cheap and easy-to-implement solutions. They designed adjustable seats — technology that is now standard in all cars. They designed adjustable pedals. They designed adjustable helmet straps and flight suits.

After these and other design solutions were implemented, the efficiency of the pilots increased. Soon, similar requirements were put forward for each branch of service in the American army, that equipment and equipment should correspond to a large range of body parameters, rather than medium.

Why did the military want to make such a radical change so quickly? Because changing the system was not an intellectual exercise — it was a practical solution to an urgent problem. When pilots at supersonic speeds need to perform a difficult maneuver using a complex array of controls, we cannot allow any sensor to be out of sight or it’s difficult to reach the switch. When vital decisions are made in a split second, the pilots were forced to take them in an environment that was already opposed to them.

In the early 1950s, Americans measured the bodies of more than 4,000 pilots, according to 140 characteristics, to design the perfect cockpit for the average pilot.

In the late 1940s, the US Air Force had a serious problem: the pilots lost control of the aircraft. Then came the era of jet engines, so that the aircraft became faster and more difficult to manage. But catastrophes happened so often and on so many different planes that the USAF faced the real problem of saving lives. At worst, up to 17 pilots were broken in a day.

For such non-combat accidents, there were two official designations: accidents ( incidents ) and accidents, and they ranged from an unintended dive and a bad landing to fatal accidents and the destruction of an aircraft. At first, the aviation authorities dumped the blame on people in the cockpits, calling the "pilot error" the main reason in the accident reports. Such an assessment seemed reasonable, since in the aircraft themselves technical failures were rare. Engineers confirmed this again and again, testing mechanics and electronics, where they did not find any defects. The pilots were also confused. One thing they knew for sure: that their piloting abilities are not the cause. If this is not a human or mechanical error, then what is it?

')

After numerous investigations without answers, officials paid attention to the design of the cabin itself. Back in 1926, when the army designed the very first cockpit, the engineers measured the physical parameters of hundreds of male pilots (no one seriously considered the possibility of controlling the aircraft of a woman), and used this data to standardize the size of the cockpit. Over the next three decades, the size and shape of the chair, the distance to the pedals and the steering wheel, the height of the windscreen, and even the shape of the helmet corresponded to the average parameters of a 1926 pilot.

Now, military engineers began to wonder if the pilots had grown since 1926. To get the new values of the physical parameters of the pilots, the air force initiated the largest research pilots ever conducted. In 1950, more than 4,000 pilots were measured by 140 size parameters at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, including the length of the thumb, the height of the perineum, and the distance from the eye to the ear. As a result, they calculated the average value of each parameter. Everyone believed that a more thorough calculation of the parameters of the average pilot would lead to the creation of a more comfortable cockpit and reduce the number of accidents. Or almost everything. One 23-year-old scientist who recently entered the service had doubts.

Lieutenant Gilbert S. Daniels did not look like a typical character of air battles boiling from testosterone. He was thin and wore glasses. He liked flowers and landscape design, and in high school, Gilbert headed the botanical garden club. Before being distributed to the aeromedical laboratory at Wright-Patterson air base right after the university, he never flew an airplane. But that didn't matter. As a novice researcher, he was assigned to measure the limbs of the pilots with the help of a tape measure.

For Gilbert, this was not the first time. Aeromedical Laboratory took it, because at Harvard the student specialized in physical anthropology, which studied the anatomy of people. In the first half of the 20th century, this area of science largely focused on the classification of human personalities by types of groups according to their average body shape - a practice known as “typing”. For example, many physical anthropologists believed that a low and heavy figure corresponds to funny and funny people, and high hairline and plump lips reflect a "criminal personality type."

However, Daniels was not interested in typing. Instead, his thesis contained a rather laborious and painstaking comparison of the shape of the hands of 250 Harvard male students. All students were similar in ethnic and socio-cultural status (that is, white and rich), but unexpectedly for anthropologists there was no similarity in their hands at all. Even more surprising, Daniels discovered, the average hand didn’t match any of the individual measurements! There was no such thing as a medium sized hand. “When I left Harvard, it was clear to me that for designing something for a particular human being, the average parameters were completely useless,” Daniels told me.

So when the army landed the young Gilbert to measure the pilots, he held a secret belief about the average size, which contradicted almost a century of the military design philosophy. Sitting in the aeromedical laboratory, measuring his arms, legs, waist and foreheads, he continued to ask himself the same question: How many pilots really have an average size?

Gilbert decided to find out. Using data from 4063 pilots, Daniels calculated the average of 10 physical characteristics that were considered most important for design, including height, chest circumference and sleeve length. So he got the dimensions of the "average pilot", which the researcher considered such, whose parameters are in the average 30% of the range of values for each parameter. So, for example, when, after the calculation, an exact average height of 175 cm was obtained, Daniels determined a height of 170 to 180 cm for the “average pilot”. Then he carefully, one by one, compared each individual pilot with average values.

Up to this point, the generally accepted opinion among fellow researchers from the Air Force was that the absolute majority of pilots would fit into the average range for most parameters. In the end, the pilots initially underwent a preliminary selection in order to meet the average parameters. (For example, if your height is 200 cm, then you will never be taken as a pilot in the first place). Scientists assumed that a significant number of pilots would correspond to the average range in all 10 parameters. But Gilbert Daniels was amazed when he determined the true number of such pilots.

Zero.

Of the 4063 pilots, not one person corresponded to the average range in all 10 parameters. One had arms longer than average and legs shorter than average, the other could have a wide chest, but small hips. What is even more striking is that Daniels found out that if you take just three out of ten size parameters - for example, neck circumference, hip circumference and wrist circumference - less than 3.5% of the pilots corresponded to the average parameters for all three indicators. Daniel's conclusions were clear and irrefutable. there was no such thing as an average pilot . If you design the cockpit for the average pilot, then in reality it will not be suitable for anyone.

Daniels revelation was so significant that it could end the era of basic assumptions about individual features and start a new era. But even the most important ideas require proper interpretation. We like to think that the facts speak for themselves, but in reality this is not so. After all, Gilbert Daniels was not the first to discover the absence of an average person.

The norm was designed to demonstrate “ideal” female forms as measured by 15,000 young adult women. The statue was installed in the Cleveland Medical Museum, created by a gynecologist Dr. Robert L. Dickinson (Robert L. Dickinson) and his assistant, Abram Belskie

Wrong ideal

Seven years earlier, the Cleveland newspaper Plain Dealer announced a competition for illustration for the front page, and the Cleveland Medical Museum, the Cleveland Medical Academy, the medical school, and the Cleveland Education Council also sponsored. The winners of the contest were promised military bonds for $ 100, $ 50 and $ 25, and ten more lucky girls could qualify for military brands with a face value of $ 10. Competition? The girls were asked to send the parameters of their bodies, which are closest to the parameters of a typical woman, Norma, which is immortalized in a statue from the Cleveland Medical Museum.

Norma was the creation of the famous gynecologist Robert L. Dickinson and his assistant Abram Belsky, who made a figure by measuring 15,000 young adult women. Dr. Dickinson was an influential figure for his time: Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Brooklyn Hospital, President of the American Society of Gynecologists and Chairman of Obstetrics at the American Medical Association. He was also an artist - Rodin from obstetrics, as one colleague called him - and his entire career made sketches of women, their various shapes and sizes, studying the relationship of body types and behavior.

Like many scientists of those days, Dickinson believed that the truth can be determined by collecting and averaging a large amount of data. "Norm" personifies such a truth. For Dickinson, the collection of thousands of indicators of the size of the female body and the calculation of the average value provided an insight into a typical female physique — someone normal.

Simultaneously with the display of the statue, the Cleveland Medical Museum began selling miniature reproductions of Norma, advertising her as the “Perfect Girl,” giving a start to the real mania around Norma. One well-known physical anthropologist said that Norma's physique is "a kind of perfection of bodily form," the artists proclaimed her beauty as a "great standard", and physical education teachers showed her as a demonstration of how a young girl should look. They prescribed to perform individual exercises based on the specific differences of the individual student from the ideal. Norma was printed in Time magazine , she was in newspaper cartoons, and in the documentary series on CBS ( This American Look ) her parameters were read out loud so that every girl could check that she had a normal body too.

On November 23, 1945, Cleveland Plain Dealer announced the winner: a slender brunette, a theater teller named Martha Skidmore. The newspaper wrote that Skidmore loves to dance, swim and play bowling - in other words, her tastes are just as normal as her figure, which was considered the ideal of female forms.

Before the competition, the judges assumed that the parameters of the majority of the contestants would be quite close to the average, and that millimeters would have to be considered to determine the winner. In reality, nothing like this was close. Less than 40 out of 3,864 contestants fell into an average size of just 5 out of 9 parameters, and not a single contestant — not even Martha Skidmore — was close to the average for all 9 parameters. Just as Daniels’s study determined the absence of such a notion as an average pilot, the competition for the role of Norma showed that an average woman does not exist either.

But although Daniels and the contest organizers got the same result, they made completely different conclusions from this. Most doctors and scientists of that time did not consider at all that Norma was the wrong ideal. Quite the contrary: they concluded that most American women are unwell and do not maintain their normal form. One of these was Dr. Bruno Gebhard, director of the Cleveland Medical Museum: he lamented that post-war women were largely unsuitable for military service, and reproached them by mentioning poor fitness, making them “poor producers and poor consumers ".

Daniels’s interpretation was exactly the opposite. “The tendency to think in terms of the" average man "is a trap that many lead to miscalculations," he wrote in 1952. “It’s almost impossible to find an average pilot not because of some individual features of his group, but because of the large variation in body size of all people.”

Instead of suggesting pilots to make efforts to comply with the artificial ideal of normality, Daniels analysis led him to a conclusion that seemed to contradict common sense and is the cornerstone of his book: any system designed for the average person is doomed to failure . ”

Daniels published his results in 1952 in a technical note of the Air Force called The "Average Man"? In it, he argued that if the army wants to improve the effectiveness of its soldiers, including pilots, it must change the design of any environment in which soldiers are supposed to work. Radical changes are recommended: the environment should correspond to individual parameters, not the average.

Surprisingly, to the honor of the air force, they listened to the arguments of the scientist. “The old designs of the Air Force were all based on a search for pilots similar to the average pilot,” Daniels explained to me. “But when we showed them that the average pilot was a useless concept, they found the strength to focus on designing the cockpits individually for each pilot. That's when the situation began to change for the better. "

Rejecting the orientation on average values, the Air Force initiated a revolution in the philosophy of military design, based on the main principle: individual adjustment. Instead of fitting a person to the norms of the system, the army began to customize the system for an individual. Immediately, the United States Air Force made new demands that the cockpits fit all pilots whose dimensions fall within the range of distribution between 5% and 95% for each characteristic.

When the aircraft manufacturers learned about the new requirements, they started abutting, insisting that the changes would cost too much and take years to solve the related engineering problems. But the military refused to compromise, and then - to everyone's surprise - aviation engineers very quickly offered rather cheap and easy-to-implement solutions. They designed adjustable seats — technology that is now standard in all cars. They designed adjustable pedals. They designed adjustable helmet straps and flight suits.

After these and other design solutions were implemented, the efficiency of the pilots increased. Soon, similar requirements were put forward for each branch of service in the American army, that equipment and equipment should correspond to a large range of body parameters, rather than medium.

Why did the military want to make such a radical change so quickly? Because changing the system was not an intellectual exercise — it was a practical solution to an urgent problem. When pilots at supersonic speeds need to perform a difficult maneuver using a complex array of controls, we cannot allow any sensor to be out of sight or it’s difficult to reach the switch. When vital decisions are made in a split second, the pilots were forced to take them in an environment that was already opposed to them.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/391425/

All Articles