White spots right

The world has completely plunged into the era of digital technology and the Internet. With the development of search engines, online media, social networks and the accumulation of a huge reservoir of personal data, the user's right to protect privacy in the network is increasingly becoming the subject of not only public debate, but also litigation. One of the defense mechanisms was the so-called “right to oblivion” or “the right to be forgotten” (Right To Be Forgotten), around which in recent years a lot of noise and discussions in different countries.

The beginning was made when in 2014 the European Court of Justice (CJEU - Court of Justice of the European Union) in the decision in the case of Google Spain v. AEPD and MK. Gonzalez explained that data subjects have the right to remove information about them from search results (delisting, de-listing) if such information is “incorrect, irrelevant or redundant” (inadequate, irrelevant or excessive).

')

Since then, Google has introduced a special section in its Transparency Report reports in which it publishes statistics on the use of the “right to be forgotten” in Europe with the publication of examples when the IT giant satisfies or reject user requests to remove information about them from the search result.

Well, the very first such case started because of the complaint of a Spanish citizen Mario Costeja González, who was dissatisfied with the fact that an article in the Catalan newspaper “La Vanguardia” dated 1998 was issued in Google search results which refers to the auction in connection with his debts and the arrest of the house. He claimed that this information directly violated his right to privacy, since he has since paid all his debts. According to Gonzalez, this publication could potentially cause irreparable damage to both its public image and its business, providing potential customers with inaccurate information about its financial position. Gonzalez demanded that the Catalan newspaper remove or change information, and from Google, remove it from the search results. As a result, the case was referred to the EU Court of Justice, which set this known precedent.

Having resolved this dispute, the court also formulated the criteria for removing information from search engines, stating that in each individual case it is necessary to evaluate a number of circumstances:

- whether such information is of public interest;

- Does not violate the rights of users to access information;

- Will delisting not restrict the right to freedom of speech (for example, for authors of materials, site owners and online media).

This landmark case gave impetus to the establishment of a new standard for the protection of the right to privacy. Legislative bodies of different countries have responded to this loud case, having normatively established the right to oblivion, including Russia.

The right to oblivion in the international arena

The right to privacy is guaranteed and by article 8 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (Rome, November 4, 1950), this international treaty is one of the fundamental documents of the Council of Europe, of which Russia is also a member.

The jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) includes questions on the interpretation and application of the Convention. In the Von Hannover v. Germany case (N 2) (Von Hannover v. Germany N 2, on the complaint NN 40660/08 and 60641/08, Resolution of February 7, 2012), the ECHR clarified that when searching for a balance between the right to freedom of expression opinions and the right to privacy in principle, both rights deserve the same respect.

The court found a number of relevant circumstances in finding a balance between these rights:

- the contribution that controversial information makes to a discussion on a subject of public interest;

- degree of fame of the person involved;

- subject (topic) of publication;

- prior behavior of the person involved;

- the consequences of publication;

- circumstances under which photographs were taken (when applicable).

In turn, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media (from 2010 to 2016), Dunja Mijatović, believes that “private information related to public figures and public interests should always be available to the media; sites and search engines should not be subject to restrictions and be held accountable in this context; excessive burdens and restrictions imposed on intermediaries and content providers cause risks of soft censorship or self-censorship. ”

International non-governmental organizations have also formulated recommendations regarding the application of the right to oblivion. For example, the organization “Article 19” in January 2018 formulated and published the Global Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy (Global Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy), developed in collaboration with experts from around the world based on existing documents and recommendations of international organizations. The document also refers to another important international document - the “Manila Principles” , which contain clear requirements for content removal requests, and earlier, in 2015, “Article 19” published the results of the legal analysis of the Russian norms on the “right to oblivion”, correlating them with international standards on this topic.

One of the global principles formulated by the “Article 19” organization is devoted to the “right to oblivion” and delisting. Principle N18 “Requests for deletion from search results” contains a list of factors that, according to experts, should be taken into account when deciding whether to exclude any information from the search results:

- whether the information relates to the privacy or personal data of the applicant;

- whether the applicant had reasonable grounds to expect such information to be kept secret or the information in question became publicly available as a result of the actions of the applicant himself;

- whether such information is of public interest;

- whether such information relates to a public figure;

- whether such information is contained in open sources (in the publicly available electronic systems of state bodies, journalistic or scientific materials, works of art);

- whether such information causes substantial harm to the applicant;

- how long such information was published and whether it retains public value;

- whether it is more expedient to use alternative remedies, such as a request to delete content from the site owner, on which the content was originally posted; defamation complaint; those. whether such protections should first be exhausted or used at all instead of a request to remove from the search results;

- whether delisting is proportional to the restriction of the right to freedom of expression, taking into account all the circumstances of the case.

Also, Article 19 states that the scope of the right to oblivion must be strictly limited to the domain name of the country in which this right is recognized and where significant damage has been done to the person.

However, in recent years, global law enforcement practice has tended to ensure that search engines must remove information from search results not only in the national domain, but also in domains around the world. Google on this score believes that “no country should extend its rules to citizens of other countries, especially when it comes to legal content.” The case of the legality of a global delisting involving Google and the French regulator for the protection of personal data is now being considered by the EU Justice Court. The case began three years ago, when the French regulator for the protection of personal data (CNIL) demanded that Google delist certain information in all domains, not only in the domains of the European Union. CNIL believes that the right to oblivion does not actually work because users outside Europe still see links in search results, and there are technologies that allow circumventing filtering.

In general, there is a uniform attitude of the ECtHR and the European Court of Justice to the mechanism for applying the right to oblivion: it is necessary to assess the situation on the basis of a criterion of public importance, a criterion of protecting the right to freedom of speech, a criterion of the nature and nature of the disputed information.

The right to oblivion in Russia

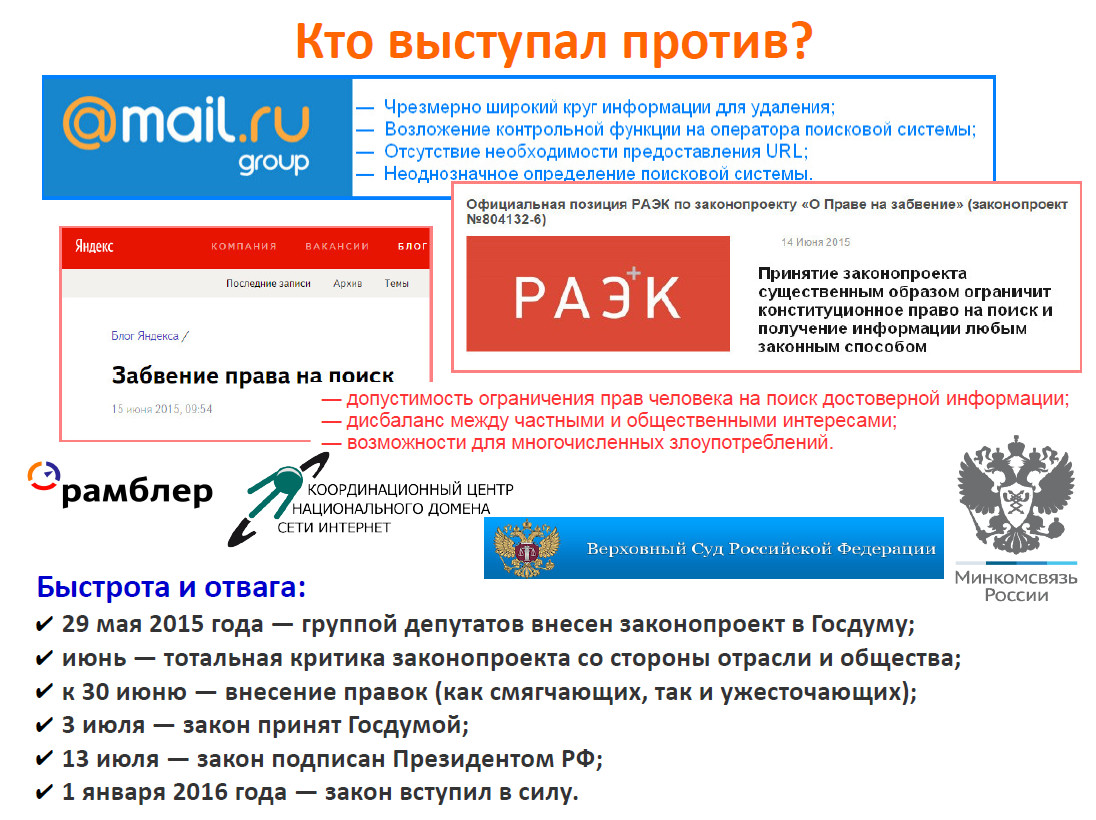

Russia also enshrined in the law the right to oblivion, despite widespread industry criticism and public outcry .

From January 1, 2016, Federal Law No. 264- came into force, which introduced Article 5 of the Law. 10.3 of the Federal Law No. 149- “On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection”. This provision allows the user (applicant) to require the search engine operator to remove from the search results links to pages of sites that contain information about the applicant, if at least one of the following is respected:

- information is distributed in violation of the legislation of the Russian Federation;

- information is unreliable;

- information is not relevant;

- the information has become meaningless to the applicant due to subsequent events or actions of the applicant.

At the same time, it is important to note that the law prohibits the deletion of information on outstanding convictions (Section 10.3 of the Law “On Information”). Simultaneously with Article 10.3 of the Law “On Information”, relevant amendments were made to the Civil Procedure Code of the Russian Federation: Part 6.2 of Art. 29 provides the plaintiff to sue at his place of residence. However, a special judicial procedure for appealing a delisting for site owners, authors whose rights to freedom of speech on the network may be violated, was not determined by the legislators.

When the “law on the right to oblivion” only came into force, its implementation took on very odd forms.

For example, in the spring of 2016, the Solnechnogorsky Court of the Moscow Region decided to deregulate the domain of the RIA FederalPress website following a complaint from two entrepreneurs who did not like the availability of information about their business litigation and who could not clear out the references to their names using the “oblivion law”.

And the chairman of a dacha cooperative, who demanded from the online publication NewsProm.Ru (in the form of a simple statement) to remove a number of articles published on this portal, which, in his opinion, have lost their relevance, harm his business reputation, and also cause a negative attitude from the owners of land. It is obvious that the applicant was wrong, because the law on the right to be forgotten applies only to search engines, not the media.

Russian practice on the right to oblivion shows that search engines more often refuse to exclude links from search results. As follows from the report of Yandex , as of the end of March 2016, Yandex satisfied only 27% of the total number of processed requests, 73% of the requests were rejected (including 9% each with a partial refusal (satisfied the requirements for some links from the circulation) As for Google , the company refused to 56.7% of user requests, and satisfied 43.3% of calls (Google data applies only to users of the European Union).

Such refusals were expected and provoked citizens who were dissatisfied with the caution of search engines during the implementation of delisting, to submit applications to the courts of residence according to part 6.2 of Art. 29 Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation. The relevant judicial practice indicates that telecom operators, as a rule, refuse to citizens lawfully and fairly, and the reason is the mistakes of the applicants themselves in the interpretation and application of art. 10.3 of the Law "On Information".

Taking into account judicial practice, citizens-applicants should consider the following nuances of the realization of the “right to oblivion”:

- When sending a request to the search engine operator, it is necessary to clearly indicate what kind of information on each of the pages is unreliable, irrelevant or distributed in violation of the law, also attach a full list of links to such pages.

- Provide proof that the information on the pages applies to you (for example, a copy of your passport).

- Provide evidence of the loss of relevance of the information or its inaccuracy or distribution in violation of the legislation of the Russian Federation (for example, a court decision confirming the fact of disseminating information discrediting honor, dignity or business reputation, a court decision recognizing information on the Internet is untrue, etc.).

- If the search engine operator needs additional documents (this may be including an identity document) in order to make a decision on delisting, be sure to fill in the required information within the established deadlines, eliminate inaccuracies and errors.

- It is worth noting that often requests to remove information about a canceled criminal record are not satisfied, therefore, it is worthwhile to pay attention to the provision of all evidence as much as possible.

When considering cases of the “right to oblivion”, the courts have repeatedly noted that search engines are not empowered to establish the fact of reliability or inaccuracy, relevance or irrelevance of information posted on third-party websites . Therefore, applicants should independently collect documents confirming the grounds for delisting, merely indicating irrelevance, inaccuracy or illegality of information will not be enough.

Separately, it is worth explaining the logic of the courts when considering cases of the “right to oblivion” regarding the deletion of information on the applicant's criminal record. This category of information is specified in Art. 10.3 of the Law “On Information” as an exception to the rule, and not as one of the categories of information that can be removed from the search result on the “right to oblivion”.

However, some applicants perceive this rule in such a way as if the redemption of a criminal record automatically makes information on a criminal record and the relevant court case irrelevant, and therefore it must be removed from the search engine. However, this is not the case; irrelevance must be proved by additional means and arguments.

For example, in case no. 2-1479 / 16 of a citizen’s appeal against the refusal of “Yandex” to stop issuing references allowing access to the text of the sentence in relation to the claimant, the Privokzalny District Court of Tula took the side of the search engine operator and supported the preservation of links to the specified information in the search results. According to the decision of September 21, 2016, the court concluded that the possibility of searching, receiving, transmitting and disseminating information about the crime committed by the claimant on the pages indicated by him should be retained, because the text of the court decision is copied on these pages Currently available for viewing on the site (ie, the relevance of the information is preserved).

In Russian judicial practice, there is also an example with the opposite logic, when references to criminal record information were still deleted by the search system operator, and the distributor of information did not agree with that.

For example, the case on the claim of the public organization Center Sova, which received two notifications from Google about the removal of links to 2 news notes on criminal cases of convicted neo-Nazis, is at the cassation appeal stage . Neo-Nazis committed a socially dangerous crime (they beat up Angolan and tagged video clips of beatings on the network), and removing any information about these cases is contrary to the criterion of social significance, therefore the Sova Center intends to restore Google’s search results news notes. So far this is the only known lawsuit initiated not by the citizen-applicant, but by the owner of the site and the distributor of information who does not even want to partially disappear from the search results.

Conclusion

The emergence of the right to oblivion blurred the boundaries between public and private individuals, expanded the latter’s decision-making responsibilities, similarly to judicial bodies. Correctly balancing the clash of fundamental rights: the right to privacy, the right to access information and the right to freedom of speech, is a daunting task.

Obviously, the Russian legislator should make appropriate amendments to the legislation, detailing the essential circumstances that should be taken into account when deciding to apply the right to be forgotten or to refuse, while taking into account the principles developed by international organizations and courts. This will make it possible to properly expand the ability to control their personal data, while not violating other fundamental rights, such as the right to freedom of speech and access to information.

Many existing laws inevitably had to come into conflict with modern technologies, and only a broad discussion and reform of the law can resolve this conflict.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/374261/

All Articles