Parallax: Deep Vision

How do we determine the depth - the distance from our location to another object? There are several ways to do this, and one of the most common and easy to understand includes such a geometric phenomenon as parallax . This extremely simple principle is used by our eyes and the brain to form our three-dimensional image of the world, and astronomers have used it for centuries to determine distances (or relative distances) from the Earth to astronomical objects.

Another common way to determine distances involves sending a wave (sound, light, something else) traveling at a known speed, which is reflected from the object and returns to us; the time taken to return the wave - echo - tells us the distance to the object. According to this principle, bats determine the distance to food and obstacles, and the radar also works.

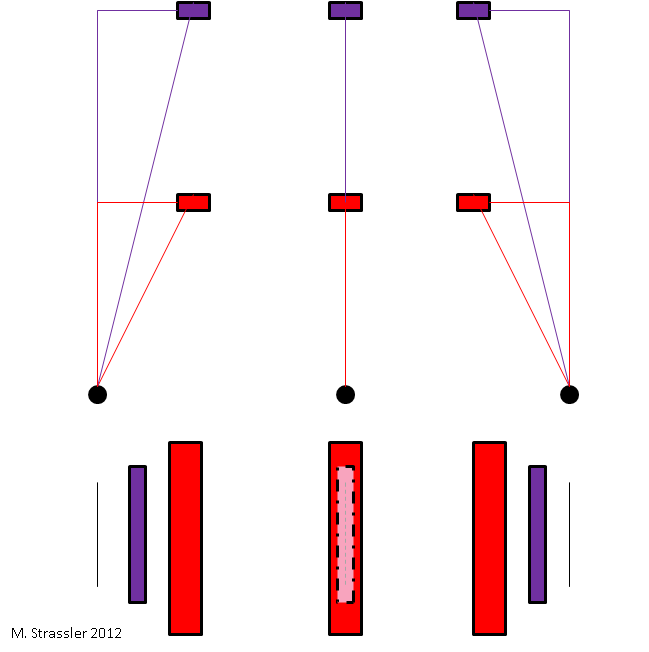

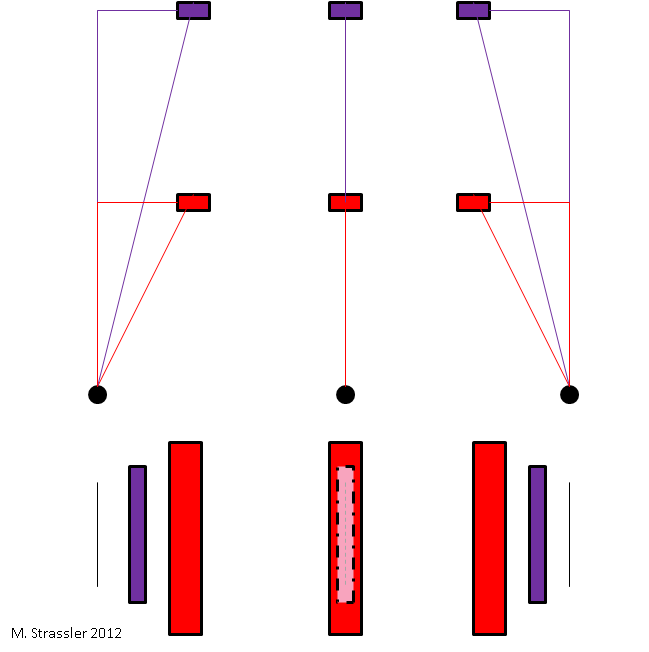

Fig. one

We perceive parallax without even thinking about it, every time we move our heads. Imagine what will happen if your friend hides from you, standing a few meters behind a large tree (Fig. 1, in the center). If you move far enough left or right, your friend will be visible (Fig. 1, left and right). We know that the whole matter is simply in perspective; at a certain angle of view, the tree will no longer block your mysterious friend. Geometrically what is happening is shown in Fig. 1. When you move left and right, looking forward, nearby objects change their angle relative to what is right in front of you, faster than objects further away. From the rate of change of the angle when you move - from the movement parallax - you can understand how far the object is located.

')

Every child knows this, because when you look out the window of a moving car, lampposts rush past very quickly, distant buildings pass more slowly, and the Moon, which is so far away that the angle of view relative to the observer does not change by a noticeable amount as the car goes on the highway, as if moving with the car. It is a small parallax, which is a consequence of a great distance, that causes the moon to “follow the machine”.

Anyone who watched old two-dimensional cartoons (and many modern ones), such as the Flintstones, know that this fact is used to depict depth. When characters travel in a car, moving from left to right, the car is drawn still, trees are drawn in another layer, which moves from right to left at high speed, and hills in the distance draw on the third layer, which moves from right to left a little slower (see Fig. 2) .

Fig. 2

Our ability to perceive depth, even without moving our head, is based on the same principle. The left and right eyes see the world from slightly different angles. Try to place a couple of objects - no matter what, even if it will be your thumbs - so that one of them is twice as far as the other, and is right behind it. Close your left eye and look at them with your right; then change eyes; then change it again, and do it a few times - and you will see that the objects move, as in fig. 1, only your left eye will see the nearest object to the right of what is next, and the right eye will see it slightly to the left.

So why do you perceive these objects with the help of both eyes as if they are one after the other? Your optical system has a very clever information processor - a kind of computer. For you, he creates not such a picture of the world, which your eyes see directly, but a picture built on its basis with the help of complex transformations. You can perceive the depth of information obtained from two eyes and combined together (this is mainly - although the movement parallax also contributes). None of your eyes can determine the depth if you are standing still. Try to close your eyes, turn the other way and open one eye. Can you accurately describe the distance to the items? The world looks flatter, more two-dimensional than usual. With both eyes open, you have no such problems. This use of two images to use a three-dimensional world map is called a stereo effect .

But even with one open eye, you can quickly appreciate the depth if you move your head. Your brain is able to use motion parallax — a faster change in the angle of view of nearby objects relative to distant ones when moving left or right — to help restore some of the depth information that is usually obtained by comparing the view from two different eyes (Fig. 2).

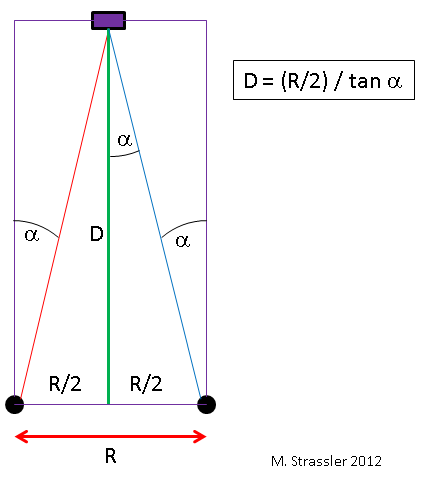

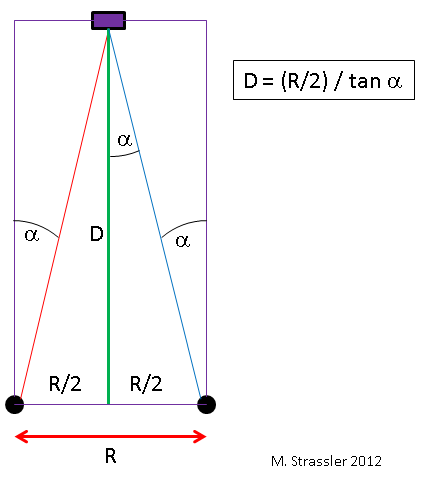

Fig. 3

What are the main calculations used by our optical system? The simplest case is shown in fig. 3. Suppose an object is right in front of you. If your eyes are at a distance R from each other, and your left eye sees an object at an angle α to the right in relation to the look straight ahead, and the right eye sees an object at an angle α to the left, then according to the simplest geometry of right-angled triangles, the distance D to the object will be dress

From the formula it can be seen that when D is smaller, the angle at which the line of sight at the object is separated from the direct view becomes larger. This is what we expect from parallax.

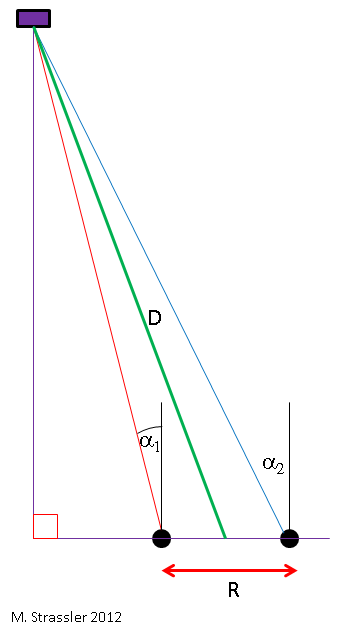

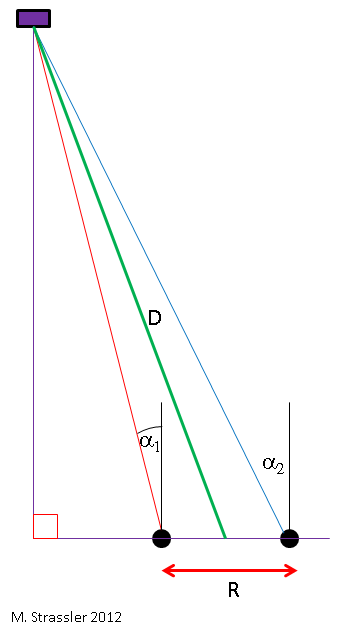

In the more general case shown in fig. 4, when the object is not directly in front of you, it turns out to be slightly more complicated, like trigonometric formulas, but the same basic principle works in it and, as a result, it is not so difficult to calculate. Your brain makes such calculations so quickly (using a technique that we haven’t yet discovered) that you don’t even know about it.

For sufficiently distant objects, the angle α is too small to be perceived by your eyes and brain. At this moment, your sense of depth disappears. Therefore, the Moon does not seem located closer than the stars; they are too far away to feel the depth. Also, your sense of depth is usually not enough to understand whether the plane will pass in front of or behind a mountain in the distance. But this is just a limitation of your eyes.

Fig. four

How to determine the distance to more distant objects? There are two options; develop a scientific instrument that can measure angles more accurately than your eye; increase R to compare not the view from the eyes, but, for example, the view from two cameras standing a few meters from each other, or even in different places of the continent. And when astronomers want to measure the longest distances that can be measured using parallax, they compare the images of a distant star made with a difference of six months to get the maximum distance R on the basis that the Earth travels a rather large distance over the course of a year. The details of these techniques are different, but the basic principle is the same as shown in fig. 3 and fig. 4 - the principle of parallax.

Another common way to determine distances involves sending a wave (sound, light, something else) traveling at a known speed, which is reflected from the object and returns to us; the time taken to return the wave - echo - tells us the distance to the object. According to this principle, bats determine the distance to food and obstacles, and the radar also works.

Fig. one

We perceive parallax without even thinking about it, every time we move our heads. Imagine what will happen if your friend hides from you, standing a few meters behind a large tree (Fig. 1, in the center). If you move far enough left or right, your friend will be visible (Fig. 1, left and right). We know that the whole matter is simply in perspective; at a certain angle of view, the tree will no longer block your mysterious friend. Geometrically what is happening is shown in Fig. 1. When you move left and right, looking forward, nearby objects change their angle relative to what is right in front of you, faster than objects further away. From the rate of change of the angle when you move - from the movement parallax - you can understand how far the object is located.

')

Every child knows this, because when you look out the window of a moving car, lampposts rush past very quickly, distant buildings pass more slowly, and the Moon, which is so far away that the angle of view relative to the observer does not change by a noticeable amount as the car goes on the highway, as if moving with the car. It is a small parallax, which is a consequence of a great distance, that causes the moon to “follow the machine”.

Anyone who watched old two-dimensional cartoons (and many modern ones), such as the Flintstones, know that this fact is used to depict depth. When characters travel in a car, moving from left to right, the car is drawn still, trees are drawn in another layer, which moves from right to left at high speed, and hills in the distance draw on the third layer, which moves from right to left a little slower (see Fig. 2) .

Fig. 2

Our ability to perceive depth, even without moving our head, is based on the same principle. The left and right eyes see the world from slightly different angles. Try to place a couple of objects - no matter what, even if it will be your thumbs - so that one of them is twice as far as the other, and is right behind it. Close your left eye and look at them with your right; then change eyes; then change it again, and do it a few times - and you will see that the objects move, as in fig. 1, only your left eye will see the nearest object to the right of what is next, and the right eye will see it slightly to the left.

So why do you perceive these objects with the help of both eyes as if they are one after the other? Your optical system has a very clever information processor - a kind of computer. For you, he creates not such a picture of the world, which your eyes see directly, but a picture built on its basis with the help of complex transformations. You can perceive the depth of information obtained from two eyes and combined together (this is mainly - although the movement parallax also contributes). None of your eyes can determine the depth if you are standing still. Try to close your eyes, turn the other way and open one eye. Can you accurately describe the distance to the items? The world looks flatter, more two-dimensional than usual. With both eyes open, you have no such problems. This use of two images to use a three-dimensional world map is called a stereo effect .

But even with one open eye, you can quickly appreciate the depth if you move your head. Your brain is able to use motion parallax — a faster change in the angle of view of nearby objects relative to distant ones when moving left or right — to help restore some of the depth information that is usually obtained by comparing the view from two different eyes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3

What are the main calculations used by our optical system? The simplest case is shown in fig. 3. Suppose an object is right in front of you. If your eyes are at a distance R from each other, and your left eye sees an object at an angle α to the right in relation to the look straight ahead, and the right eye sees an object at an angle α to the left, then according to the simplest geometry of right-angled triangles, the distance D to the object will be dress

From the formula it can be seen that when D is smaller, the angle at which the line of sight at the object is separated from the direct view becomes larger. This is what we expect from parallax.

In the more general case shown in fig. 4, when the object is not directly in front of you, it turns out to be slightly more complicated, like trigonometric formulas, but the same basic principle works in it and, as a result, it is not so difficult to calculate. Your brain makes such calculations so quickly (using a technique that we haven’t yet discovered) that you don’t even know about it.

For sufficiently distant objects, the angle α is too small to be perceived by your eyes and brain. At this moment, your sense of depth disappears. Therefore, the Moon does not seem located closer than the stars; they are too far away to feel the depth. Also, your sense of depth is usually not enough to understand whether the plane will pass in front of or behind a mountain in the distance. But this is just a limitation of your eyes.

Fig. four

How to determine the distance to more distant objects? There are two options; develop a scientific instrument that can measure angles more accurately than your eye; increase R to compare not the view from the eyes, but, for example, the view from two cameras standing a few meters from each other, or even in different places of the continent. And when astronomers want to measure the longest distances that can be measured using parallax, they compare the images of a distant star made with a difference of six months to get the maximum distance R on the basis that the Earth travels a rather large distance over the course of a year. The details of these techniques are different, but the basic principle is the same as shown in fig. 3 and fig. 4 - the principle of parallax.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/374213/

All Articles