Details of the creation of a man-driven sports robot weighing 3600 kg

“It's like riding a mountain bike” - only, of course, on a bike weighing 3,600 kg and 4.5 m high

If everything was the way Jonathan Tippett wants, then not only people would perform at the Olympics of the future - he predicted the emergence of human-controlled robot athletes. At a technology exhibition in Toronto in July 2017, this Canadian mechanical engineer invited us to present races in which pilots would dress in massive exobionic mekh [ not to be confused with exhibitionists; exo - from the Greek exō, "external", and bionics - applied science on the application in technical devices and systems of principles of organization, properties, functions and structures of living nature / approx. trans. ]. Treat this as an overly bloated version of a two-handed loader, which Ripley managed in “Alien,” or equipment familiar to players in Titanfall.

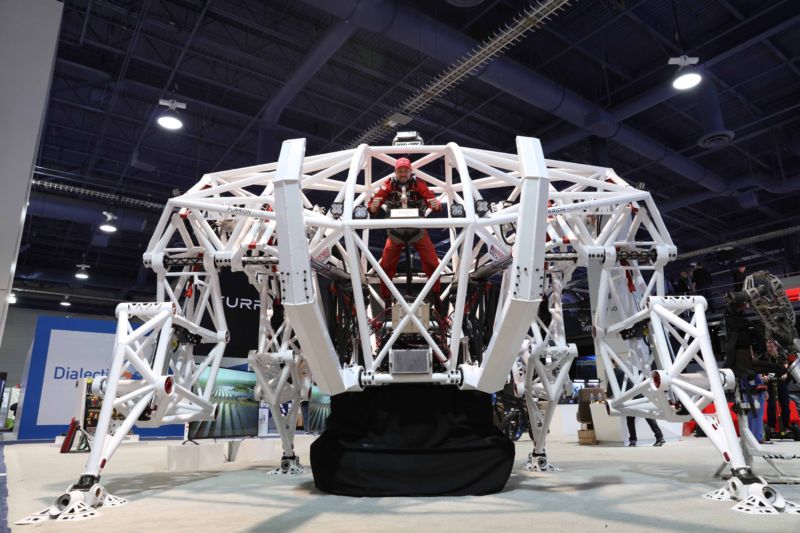

We didn’t need to strain our imagination for a long time. Tipet soon showed us the first participant in the races he offered, and the room quickly filled with sighs of surprise. Tipet introduced us to Prosthesis [eng. prosthesis - prosthesis], 4.5 m of exobionic platform weighing 3,600 kg, running on electricity, and amplifying the movement of the pilot sitting in the cockpit in the center of the fur. It is made of alloy steel containing chromium and molybdenum additives [eng. chromoly], and in the limit it is able to run at a speed of 34 km / h, jump up to 3 meters, and work without recharging for two hours.

For scale - a team of engineers

')

All this, of course, an impressive result of the work of production and engineers. But, talking to our magazine a few months later, Tipet says that his goal is more philosophical than it seems to many. “Prosthesis can be thought of as a high-tech machine, but it’s a metaphor weighing 3600 kg how technology allows us to do what we want and how important people in robotics are still playing.”

The robot from Titanfall (of course, worked much stronger)

It was in this spirit that Tipet, with his team from Indiana-based Furrion and working with him on Prosthesis, decided to add a cabin to the fur and make it an interface for controlling the person, instead of making the remotely controlled robot that we saw fighting in cages and drones races. “Prosthesis is a continuation of the pilot’s body,” Tipet says. “It's like riding a mountain bike, feeling with immediate perception, and not as an observer.”

Now Tipet is working on training pilots and adjusting the mechanics to ensure that the furs are ready to race. He will move in the manner of a gorilla - using all four limbs for walking and running - unlike us, two-legs. If Tipet wants Prosthesis to race without problems, what are his next steps in realizing this NF dream?

Ripley (aesthetically closer to Prosthesis)

But first, walking spiderbot

People meet with Prosthesis not for the first time. Giant fur has appeared at various technology fairs, for example, at CES 2017 and at the Burning Man festival this summer.

It was Burning Man that awakened the inventor in Tipet before he began work on Prosthesis. Tipet was engaged in engineering at the end of the training program for mechanical engineers at the University of British Columbia. Thanks to a small grant from the festival in Nevada in 2006, Tipet and his compatriots, engineers from Vancouver, built a robopauk Mondo, a mechanical walking spider powered by hydraulics and motors. CODE Live later commissioned engineers to remake Mondo to work on electricity for demonstration during the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. This allowed Mondo to work relatively quietly, recharge from solar energy and perform indoors without creating exhaust.

Spider Mondo, direct ancestor of Prosthesis

In 2013, Tipet said in an interview with Tested: “If you can transfer a walking spider weighing 750 kg from gasoline to electricity, then it can be done with anything at all!”

Project Mondo provoked appetite engineer Tipette. And when he began to rotate among the lovers of robots, he was already preparing the drawings of Prosthesis. Tipet needed something more, faster and better.

“Let's give the pilot the feeling of riding a wild roller coaster,” Tipet recalls the initial stages of development. “Being in a cabin four meters above the ground, using your limbs to control the movements of the fur — it disorients, terrifies, captures - and all at the same time.”

Tipetu is familiar with exciting feelings - among his hobbies are a motorcycle, a mountain bike and a snowboard. But the work on Prosthesis will be discouraging even before he has a chance to get into the cabin.

Creating a robot body

In the first approach to the development of Prosthesis, technical requirements alone discouraged Tipet. How should the suspension work for a walking unit weighing 3600 kg? How to ensure a constant balance of fur with four legs, and not eight?

The correct control cabin layout was central to the realization of the idea. The pilot, using a harness with fastening at five points, places his forearms in metal brackets, and his legs - in the holders wrapped around his calves. They are then fixed using devices that resemble a sleeve for measuring pressure.

Tipet decided to abandon the imitation of a human walk, and instead borrow the system of walking from the gorilla, down to the low-lying arms and legs. The movements of the pilot in the cockpit control the movements of Prosthesis: bend your elbow and the robot will try to sit down. Pull the limbs forward, and Prosthesis will roll.

To control the limbs, each of the legs of the fur is equipped with two hydraulic actuators. The “hip” drive is connected to the upper part of the leg and allows it to swing back and forth. The second actuator is attached to the back of the four pipe connection. The contraction of this drive shortens the leg and lifts it from the ground, while the drive of the thigh carries the leg forward. When taken off the ground, the foot moving forward is extended to meet the ground. The thigh drive can pull the leg back, and the shock absorbers support the weight of the car and soften the ride.

“The most interesting thing about all this is the responsiveness of the movements,” Tipet says. “We have been adjusting the harness, shock absorbers, cab buffers for several weeks so that everything works perfectly for the pilot.” He sighs. “Let me just say that managing Prosthesis is very difficult and exhausting.”

It can be expected that the overestimated goals in the development of Prosthesis led to a lot of trial and error. Tipet recalls how he rolled over with fur several times, comparing his feelings with another sport. “It's like a snowboard - how many times do you need to fall before you master?” - he says. “There was also a lot of trial and error with Prosthesis.”

Tipet and the team’s first step was to find the right balance, and now they are working on a smooth fur gait - not even on running yet, Tipet warns. To learn how to run, you first need to learn how to walk [ according to the American saying walk before you run / approx. trans. ].

“Observe the people who control the monster trucks as they train to create the right choreography,” Tipet says. - With Prosthesis everything is about the same. It is physically hard. But in the end, fans will like the human skill in piloting these robots. ”

He emphasizes, not for the first time, that "the machine is designed to fit the pilot, and not vice versa." Tipet adds that fur should be an extension of the human body, and create a feeling of symbiosis that is difficult to reproduce.

Jumping over obstacles

I spoke with several experts in robotics to find out what problems Tipet was expecting on his way. It may seem that the principle of movement on the feet is easy to reproduce, but it is deceptive - according to Jonathan Hirst, the technical director of Agility Robotics, it is extremely difficult. "In this motion, a well-developed mechanical system with precisely selected springs, inertia and control hierarchy is used." He adds that any hindrance for walking fur, for example, rugged terrain, can violate not only the trajectory of the movement of the legs, but also their inertia.

Who, if not him, be aware of this: in 2017, the company introduced its newest walking robot Cassie, who does not yet have a torso, and with hips with three degrees of freedom, similar to a person's hips. Such a device allows Cassie to swing her legs back and forth, sideways, and at the same time turn them.

Cassie, Agility Robotics two-legged robot

Hurst and colleagues would soon attach Cassie's arms, torso, and sensors, but for now research labs can order these legs with hips. “We believe that the robot can be useful for cargo delivery and territory research,” says Hurst about the possibilities for Cassie to use.

What Hirst and Tipet are trying to do is recalling the LS3, a short-lived walking robot from Boston Dynamics, which was advertised as a solution for military logistics tasks. Due to their limitations, the LS3 project was sent to the shelf in 2015. He made loud noises, was hard to repair, and was hardly integrated into the traditional patrol of the marines.

Hartmut Geyer, associate professor at the Institute of Robotics at Carnegie Malone University, does not want Prostozis to suffer the same fate as LS3, but it seems to him that the idea that the Prosthesis will inspire the creation of racing competitions for furs is an impossible dream. .

“The main problem lies in the management,” says Geyer. - Can powerful legs run fast enough, or are they suitable only for certain movements? And there is also a problem with overheating of the engine. ”

Some four-legged robots are already learning to overcome rough terrain, but the positive news in this area is related to the development of the University of California at San Diego, where they make a soft mango-sized soft robot. This, of course, is not fur. But still, it was made of rubber material printed on a 3D printer, and advertised as the first robot of this type, capable of walking on such rough surfaces as sand or pebbles. Also, their robot is able to change the method of movement from walking to crawling to climb into hard to reach places.

The potential for creating walking robots is so attractive that some universities devote entire units to this task - for example, the Leg Laboratory at MIT. On their website, you can track progress in researching the various stages of robots movement, from Uniroo 1991, copied from a kangaroo, to the first robot using feet and active ankles.

Race, not war

For now, it is easiest to compare the Prosthesis with similar furs from such gurus of robotics as MegaBots pushing giant furs against each other in battles. In September, fur from MegaBots, Mk. III fought with the Japanese Kuratas, produced by the Japanese company Suidobashi Heavy Industry. Co-founder of MegaBots Guy Cavalcanti told me that this was "the world's first battle of giant robots." Weight Mk. III - 6 tons, height - 4.5 m, and he is able to shoot balls with paint the size of a cannonball.

Cavalcanti compares the battles of robots driven by people from the booths with what Tipet wants to do with the Fur Racing League. “Everything is tied to human drama, to the history of man and sport,” he says. - Remove people, and the drama will subside. Look at BattleBots: this is a great show, but when the robot is falling apart into a dozen parts, the camera is switched to an upset operator with a remote control. This is not very interesting. We want to see the quarterback being demolished, the boxer being knocked out. ”

As a person who has undergone a large-scale production process, he positively assesses Tipet’s caution in not doing too much at once and not in a hurry with the preparation of Prosthesis. “We need to start without rushing, because our robots have a lot of movement,” says Cavalcanti. “He can hit his nose himself, and the pilot has a risk of getting a claw on the cockpit.”

Well, apart from the dangerous damage, Cavalcanti warns about the difficulties of creating robots for engineers, noting that "robots are a very big design problem." He recommends recalling the Model T and imagining how much cars have changed over the course of several decades — the underlying technology has undergone gradual changes. “And robots are harder than cars,” he says. “Machines have relatively few moving parts compared to humanoid robots, and such a massive robot like fur should work smoothly. With increasing scale, everything changes. Each new platform, such as robotics, needs to be nurtured for a very long time before it is released for everyone to see. ”

Prosthesis next to the office building

In addition to caring for the robot itself, Tipet thinks about the sport of races on furs. Now he draws inspiration from other athletic robots, for example, from the Drone Racing League. Teddy Tsanetos, the former head of engineering at DRL, and now a robot technology technologist at NASA, says Tipet’s key skill will be managing the hype associated with launching a new sport.

“You need to control how he makes an impression and what expectations he will have,” says Zanetos. “People, having heard about the“ fur races, ”will very easily imagine something like a computer game.” But, despite such a reasonable approach, the robot lover Zanetos has many questions for the league of furs races. “How to make really fast fur? Why is it necessary to use legs, and not something else? I would be interested. ”

So far, Tipet continues to slowly train pilots. At first, the team wanted to present the furs in Dubai, where the world's future sports games of the future will take place in December, but transporting a massive beast would be a difficult task, and, besides, it still needs to be worked on. According to the new plan, Tipet wants to make Prosthesis debut in April 2018 in the first race, the venue of which will be announced later. But the delayed debut and several obstacles didn’t stop Tipetta, and he constantly reflects on how this racing league could develop.

He says that some furs can be created for racing in ordinary terrain, while others can specialize in cross-country. Each fur will have its own personality, possibly associated with the person in the cabin. If Formula 1 racers can attract fans with their style and taste, why can't the fur pilots do this?

Perhaps the race of several furs will not take place right away. At first, it may just be running at the time when athletes will replace each other in the cabin of Prosthesis. Since the fur is controlled by the movements of a person, the speed and power of his run depend on the skills of the pilot. “Creating furs is an ambitious task, and I know that the barrier to entering this area is very high.”

But, despite all the problems, Tipet is optimistic about the possibility of creating a racing league of bellows. “When pilots demonstrate their skills and everything that their cars are capable of, it will excite everyone, especially people with money.” And, as in any industry, the emergence of hype and money will begin to fuel development in this area.

Tipet is not going to stop at the races of furs. "Holy Grail" for him is the participation of furs in the Olympics. But, as Prosthesis, you must first learn to walk, before running, not to mention competing, Tipet is ready for a while to confine himself to a less audacious dream. He does not exclude other types of events that can demonstrate all the possibilities of Prosthesis and the like.

“Why not make a show during the Super Bowl break? That would be perfect !, he exclaims. Then freezes, and you can see gears spinning in his head. - In general, if you really want to dream to the full, why not make a pin American football with furs ?! "

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/374071/

All Articles