The hunt for the best sugar

When the history of sugar is written, 2016 can be remembered as the year when its image changed. Of course, we always knew that these sweet white crystals destroy teeth and make people gain extra pounds. Obesity and diabetes have become a national disaster, with the latter costing 10% of all US health care expenditures.

But now an increasing number of researchers and the book The Case Against Sugar have also begun to associate our favorite natural sweetener with such terrible conditions as heart disease, Alzheimer's disease and cancer. (These conclusions are still far from generally accepted.) Thickening the paint can be assumed that the sugar industry paid Harvard scientists in the 1960s to minimize their role in ischemic problems, and instead the main culprit was designated saturated fats, which formed the direction of nutrition research and to this day.

“Sugar is new tobacco” in the public mind, says David Turner, global food and beverage analyst at research firm Mintel.

')

And the war for public health began. Several cities responded with taxes on sugary drinks, and next year the FDA will begin to require companies to disclose the amount of added sugars on the product packaging.

Consumers seem to hear the calls. The NPD Group research firm discovered that sugar is the No. 1 substance that they are trying to reduce or remove from their diets. Of course, “trying” is not the best word. Whatever their aspirations, people do not stop eating it. Americans now consume a total of 76 pounds of sugar each year, which is 8% higher than in 1970.

This is a problem for food companies: they are built on this. According to a recent study by The Lancet, about 74% of packaged foods and drinks in the United States contain some form of sweetener, making it a more than $ 100 billion market. Companies “use hedonistic substances, and sugar is the most ubiquitous hedonic substance,” says Robert Lustig, a professor at the University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine and chief critic for this topic. This is an academic way of saying that food companies know that customers are hungry for sugar rush.

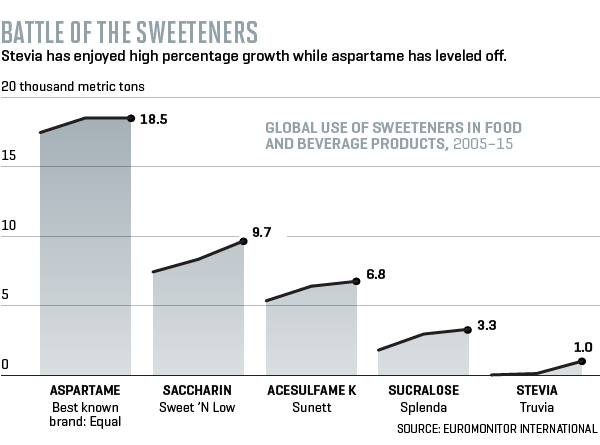

All this has poured new energy into the desire to find low-calorie sweeteners. And this is because existing alternatives face even more skepticism. According to Mintel, 39% of consumers believe that it is better to avoid products that contain artificial ingredients, such as aspartame and saccharin, because of the health risks. Sales of such substitutes fell by 13% from 2011 to 2016.

This brings us to the last factor that strongly influences food companies: an increasingly aggressive appetite for "natural", unprocessed foods. “Health and well-being used to be synonymous with reducing calorie intake,” said Bernstein analyst Ali Dibaj. According to this standard, as he put it, referring to the cult first diet cola, “Tab used to be damn healthy”. No more.

Think of the plight of food companies in this way: the best scientists in the industry have spent decades trying to find or invent a non-caloric sweetener that tastes as good as sugar extracted from pure cane. And now, after they have largely failed to cope with this difficult, difficult task, the level of complexity rises even higher: this incredible mixture cannot be designed by scientists.

Let's stop here to look at the sugar embrace of food companies and the American consumer. You can rightly blame consumers for their insistence on an impossible product. But who has indulged their fantasies for many decades, promising sweet, good taste and no calories? Companies, of course. Now, customers are increasing rates - and it’s not at all clear that companies can take the test.

It is not by chance that sugar was a food supplement 10,000 years ago. Historians monitor the first use of sugar cane in New Guinea. By 500 BC some farmers in India turned cane into raw sugar. Sucrose, as scientists know, is an almost perfect compound. She canned. It is leavened and caramelized. It provides viscosity and taste, texture and mass. It improves the taste of other ingredients. Like even a newborn will tell you that she is the gold standard of sweetness.

This did not prevent several aspirants from overthrowing it. A series of sweeteners - saccharin, aspartame and sucralose - they all appeared on the scene for decades, each of them claimed the maximum sweetness and minimum calories. Each product followed a similar trajectory: originally presented as a scientific miracle, with assurances that it tasted exactly the same as the original, it is popular before it eventually disappoints consumers with a strange aftertaste or, in some cases, causes concern about its effects on health

The most recent low-calorie miracle is stevia - the most famous brand is Truvia, and it is extolled as natural because it comes from plant leaves. The history of stevia illustrates the possibility — and the riddle — of sugar replacement missions, so I went to Illinois to visit PureCircle, the largest producer in the world.

Winter weather does not agree with stevia, which thrives in warm climates. “You have to forgive our plants,” said Faith Son, head of global marketing and innovation, and she looks at the seedlings on the table in the conference room. "This is January in Chicago." Her company has built its entire business on the small green leaves that Dream put in front of us.

The sweetness of the stevia is unexpected. For a start, it is extracted not from the fruit, but from the leaves of the plant. More surprising, however, is how sweetness is felt. Even a few minutes after I bit, chewed and spit, it stays in my mouth. “It's almost a miracle of nature,” says Son.

Compounds that give the plant its magical properties are called steviol glycosides. They are 100-350 times sweeter than sugar, and make up only a small part of the weight of the leaf. This is what the industry calls a high-intensity sweetener that delivers a taste of sugar, but not any other attributes, like its mouthfeel or texture.

Stevia was supposed to be the answer to a great dilemma. But, like its predecessors, it is burdened with a tragic flaw: a constant bitter aftertaste due to steviol glycosides, along with a metallic and licorice flavor. “It tastes like sucking a penny!” Is not a type of product that manufacturers can sell well.

Scientists believed that the antidote to bitterness lurks inside more than 40 different glycosides that were found in the leaves. In Cargill, one of the competitors of PureCircle, scientists initially believed that there was one bad actor, the only glycoside that he could remove and solve the problems of taste.

Everything turned out to be more difficult. Each chemical compound has a unique sweetness and bitterness. Cargill scientists began to classify each person’s taste profile individually and in combination to create a complex model of what works best. “It was unintuitive,” says Andy Ohms, who runs a high intensity sweetener business. In 2014, Cargill released ViaTech, a sweetening system based on this work, which combines a selection of nine glycosides approved for use. Some, including the best tastings, for example, such as Reb M, are present in less than 1% of the leaf. Cargill and PureCircle are trying to create them by crossing.

Stevia has other disadvantages. Some product developers say they are harder to use than artificial sweeteners, which are more like sugar and therefore can be more easily used as a substitute. PepsiCo CEO Indra Noah, for example, said that stevia does not work well in a stake.

Like other sweeteners, stevia enjoyed an early moment of glory. Companies that do not recognize that known glycosides can replace only 70% - 80% of sweets in typical soda, have released really awful products. At a certain point, the addition of more stevia leads to a reduction in taste and makes its drawbacks more noticeable. Stevia was used to reduce the number of calories of the product, and not completely eliminate them. Even then, glycosides act differently depending on the product. Reb A works well in tea, for example, but may not be compatible with citrus flavors. There is no single solution even for one product category. “This is an unpredictable ingredient,” says John Martin, head of technical development and innovation at PureCircle.

Currently, many companies are experimenting with the improvement or modification of sweeteners. For example, MycoTechnology in Colorado uses the root system of mushrooms to block the taste of stevia. It can also reduce the need for sugar by masking bitterness in foods such as wheat bread. Sensient in Milwaukee is looking for the right qualities in natural ingredients, such as tree roots or bark, which can increase the sweetness of sugar, so creators can use them less. Coca-Cola's Chromocell does the same job as Senomyx, which works with PepsiCo.

Most people in business believe that a “systems approach” - mixing ingredients, rather than a single molecule - is the future of the natural sweetener industry. “I don’t think you’ll see only one thing,” says Mike Harrison, senior vice president of product development for the UK giant Tate & Lyle.

For some people, all of this will never be enough to make a stevia tasty. When I was at the Tate & Lyle US office in Chicago, I tried a lemon-cucumber stevia drink made by their team. I find it light and refreshing, albeit a little sweet, with a few hints of bitterness. But I looked at my host, Harrison, and saw his grimace. “I can't drink this,” he says. "It is disgusting." After an hour, the sensation still bothered him. Harrison opened a can of beer to try to stifle the sensation in his mouth.

This is not the fault of his team. Harrison's high sensitivity is unusual, but, in truth, almost half of the population has an aversion to the bitterness of stevia. This is unacceptable for a company hoping to enter the mass market. "If you make a food product, and about 40% refuse it," says Harrison, "this is a very big problem." Another 20% of the population show no bitterness at all. It depends only on your genes. “This threshold is different for everyone,” says John Smythe, head of the Tate & Lyle sensory system.

Tate & Lyle is working on new incarnations of stevia, mixing glycosides in different ways. His second generation, which will be on the market next year, is not as bright in taste as sugar; it’s a little easier, explains Smythe (who worked for the wine company). The next generation Tate & Lyle, in development, is getting closer. But don't expect to see it on the market anytime soon. Now it's just too expensive.

However, even this expensive version has a sweetness that slowly dissipates, suggesting that the problem of stevia simply cannot be fixed. This is partly due to the fact that the taste of sugar consists not only of intensity, but also of more subtle aspects. The sweetness of sugar grows quickly, and then disappears almost as quickly. Replication requires replication of this curve. “Making the same profile looks more like a miracle,” admits Smythe.

PureCircle solves this problem by speaking in advance about the taste of stevia. "People will tell us when we come up with new ones: 'Well, this is not like sugar.' No, it tastes like stevia, ”says Son. "We recognize that they differ from each other."

However, every time I eat something sweet and it's not sugar, it seems artificial to me. That is how my brain and taste buds are connected. “We think: it tastes like sugar, well,” says Smythe. "It tastes like something else is not good."

For decades after World War II, “scientific” food production was seen as the pinnacle of progress. Today, of course, consumers want their food to be “natural” and simple.

This greatly complicated the search for a low-calorie sweetener. Buyers see products with fewer ingredients that are healthier than those with long assortments. “The goal is not to add something,” said consultant Alex Wu, who worked at Kraft and PepsiCo. If the ingredients need to be added, he says, our position is “to declare that there are no artificial flavors or sweeteners”.

This is the essence of the current dilemma. How do you develop a natural solution? For example, Cargill attempts to create some of the rarest and best tasting steviol glycosides during the fermentation process. The product, called EverSweet, was postponed due to production costs, but there is also the problem of whether consumers will perceive the product as natural if it is not derived from leaves.

The same can be said about erythritol, alcohol with calorie-free sugar, which is found in fruits, whose ingredients the company can also produce by fermenting yeast. Erythritol is often combined with stevia, especially in sweeteners such as Truvia Cargill's, to simulate the mass and volume of sugar. “Our biggest problem is that the consumer does not understand how wonderful erythritol is,” says A. Aumok, global marketing leader for Cargill for Truvia. Some of them fear its chemical name and its classification as sugar alcohol, some of them are related to what is known in polite circles as “gastrointestinal upset”.

Even stevia did not avoid the question of naturalness. Of course, it is obtained from the plant, but then turned into an extract. “There is a big discussion about whether these products are natural,” says Bernstein analyst Dibage. "Some claim that sugar is more natural than stevia." (“Natural” sugar is also made by applying chemicals to pure reeds or beets.) The FDA does not define the term “natural”, so in the end it remains to the opinions of buyers and sellers.

Some consumers clearly prefer what they perceive as pure substances - one of the reasons that cane sugar comes back all the time. They would rather agree with the dangers of too much sugar than with the possible risks of an artificial alternative.

“Everything tastes sweet, we take it and send it for analysis,” says the executive director for the search for a new sweetener.

“It’s irrational to assume that natural sugar substitutes are better than artificial ones,” says Paul Breslin, a professor who specializes in taste in the food sciences department of Rutgers University. For example, natural calorie-free sweeteners were not free from all the risks that some researchers attribute to artificial, problems with intestinal bacteria, causing metabolic dysfunction, such as glucose intolerance, and encouraging people to overeat.

“We just don’t know what is best,” says Dana Mal, deputy lab director at Yale John B. Pierce, who studies physiology and health. "We know enough to know that we do not know enough." For example, what does it mean that sweetness has always indicated the presence of calories, and now it often does not exist? And what do sweet receptors do not only in the mouth, but also in the intestinal tract? Even today, scientists do not understand what we want to replace.

When Grant Dubois joined Coca-Cola in 1992, an epidemic of type 2 diabetes loomed. It was his job to find a way to make Diet Coke as real. By the end of the decade, the extra caution was that it had to be natural. “They have already concluded that they should have excluded artificial flavors and sweeteners from their products,” he says.

Dubois and his team began scouring plant materials that had potential. They considered more than 50 possibilities. All had their flaws - some of them rather large. For example, Monatin comes from a South African plant and is 3000 times sweeter than sugar, but when exposed to light, it produces an unpleasant odor of feces. “It was awful,” says Dubois. Finding this ideal alternative is an “insane commission,” he argues. “From my point of view, the probability is less than the search for gold. The probability is essentially zero. "

Even if Dubois and his team would find something tasty, it should also be cost effective. It is difficult to beat the price of artificial sweeteners. “They are very cheap,” he explains, “cheaper than sugar.” Coca-Cola 2011 , , 60 , 24 , 50 5 . « - », – . , « ». .

– – . « , », – , .

Natur Research Ingredients Cweet, , 2000 . Miraculex , , , , -, .

Tate & Lyle . , , 70% . : , , . Tate & Lyle FDA .

, , , – luo han guo, . , , , , . , Guilin Layn Natural Ingredients, , . Guilin Layn , Mogroside V, , , .

, , . , - . «, , – , – .»

, , . , DouxMatok, , . , , , . DouxMatok . , , . , , , 50% .

DouxMatok, 99,5% , . , , , , .

Nestlé . , , . , , . « , , , , », – . 40%. – , – , , . Nestlé, .

, , : ? « , , », – . , , . , , , . , 108 73 . ?

, . Coca-Cola , 200 . , PepsiCo , 2025 100 12 . (, Pepsi 150 .) General Mills . Nestlé Dr Pepper Snapple .

, . « , 20% », – . , Nestlé, , , . « , , », – . « , , ?»

, UK 2005 50% . 2011 15%, 40%. UK .

, . , . , , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/373855/

All Articles