How to solve the checkers

The story of the duel of two people, one of whom dies, and the search for a way to create artificial intelligence

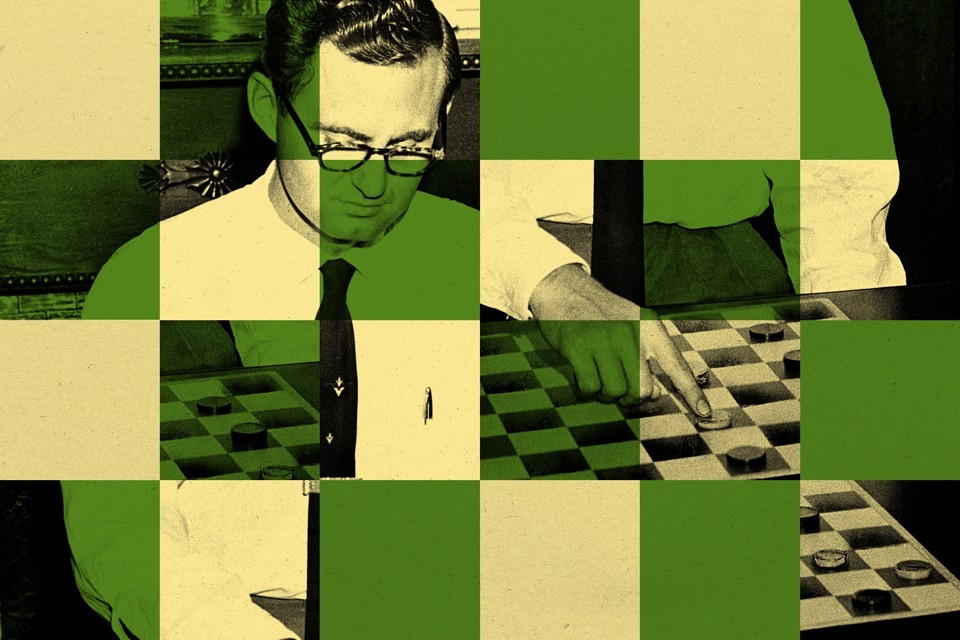

Marion Tinsley - a professor of mathematics, a priest, the best player in drafts in the world - sat at the table opposite the computer and died.

Tinsley, 40, held the first place in checkers, and during that time he lost several games to people, but he never lost the match. It is possible that in none of the competitive discipline was there such a champion as Tinsley was in checkers. But this competition was different - the world championship between man and machine.

')

His opponent was " Chinook " ("Shinuk"), a drafts program created by Jonathan Schaeffer , a man with curly hair, plump, occupying the post of professor at the University of Alberta . That day he drove the car. Thanks to the maniacal work on Shinuk, she became a very good player. She has not lost a single game in the last 125 games - and since when they came close to victory over Tinsley in 1992, Schaeffer and the team have spent thousands of hours improving the program.

On the eve of the match, Tinsley dreamed that God spoke to him, and told him: “I like Jonathan too,” which led him to believe that he had lost exclusive support from above.

And so they sat in the Boston Computer Museum, now no longer functioning. The room was large, but only a few dozen people were present. Two people planned to play 30 matches in the next two weeks. It was 1994, when there were no games of Garry Kasparov and Deep Blue, or Lee Sedol and AlphaGo.

Contemporaries described this event as a battle between man and machine, the cunning human mind and the gross computational power of a supercomputer. But Tinsley and Schaeffer agreed that it was a battle between two men who prepared themselves and set up a unique tool to defeat an opponent. So long predominating over human rivals, Tinsley was looking forward to the match with an entity with which to play well. He volunteered to take part in friendly matches to warm up before two world championship matches. Schaeffer, although he was stubborn, became the most effective promoter of Tinsley's art and heritage.

But in that room Tinsley was plagued by the peculiarities of human development. His stomach hurt. The pain kept him awake all night. After six games - all draws - he had to consult a doctor. Schaeffer took him to the hospital. He got off with “Maalox”. But the next day they saw a tumor in the pancreas on X-rays. Tinsley understood his fate.

He took the challenge. "Shinuk" was the first computer program in history that won the world championship in people. But Schaeffer was depressed. He devoted years of his life to creating a program capable of winning the best player in checkers, and as soon as he was ready to fulfill his dream, Tinsley left the game. A few months later, Tinsley died without losing the Shinuka match.

As a result, Schaeffer set off on a 13-year odyssey to exorcise the ghost of man. Without Tinsley, the only way to prove that Shinuk could have defeated him was to find a way to defeat the game itself. He will publish the results on July 19, 2007, in the journal Science, with the headline: " Checkers are solved ."

“After the end of the Tinsley saga in 94-95, until 2007, I, as an obsessive person, worked to create the perfect program for checkers,” Scheffer told me. “The reason was simple: I wanted to get rid of the ghost of Marion Tinsley.” I was told: "You could not beat Tinsley, because he was perfect." Well, yes, we would beat Tinsley, because he was almost perfect. But my computer program is perfect. ”

* * *

Jonathan Schaeffer did not start his career with the intention to solve checkers. At first he played chess. Good, but not brilliant. He also loved computers, and received a doctorate in computer science, so he decided to write a program that plays chess. He called it "Phoenix", and she was among the best among many chess programs written in the 80s. However, in 1989 at the world championship for chess-playing computers, it failed miserably. At the same time, a team that will create DeepBlue, a chess game software that will be able to defeat Kasparov, began to gather. Schaeffer realized that he would never succeed in creating a world champion among computers.

A colleague suggested that he try the checkers instead - and after just a few months of operation, his software was already good enough to go to the computer Olympiad in London and compete with other checkers bots. It was there that he began to learn the story of Marion Tinsley, the greatest.

At the highest levels, checkers are a game of intellectual exhaustion. Most games come down to a draw. In serious matches, players do not start from standard positions. For them, the debut is randomly selected after three moves from the set of approved ones, which gives a slight advantage to one or the other player. They play it, then change colors. The main way to lose is to make a mistake, for which the opponent will grab.

Apparently, checkers should easily obey the computer. This idea was vital in the mid-1950s, when a researcher from IBM, Arthur Samuel , began experimenting with programs that play checkers on an IBM 704 computer. He worked on this task for the next 15 years, published several important scientific papers on the discipline he named "Machine learning".

MO - the basic concept of a modern AI wave. The descendants of that early work today promise a revolution in entire industries and labor markets. But Samuel’s programs did not succeed in matches with human opponents. In May 1958, several members of the Endicott-Johnson Club of Checkers and Chess Corporation defeated the computer, to the delight of the Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin newspapers.

“The human brain, sometimes lost in the era of satellites, frozen food and electronic data processing machines, has returned to its former glory today,” the newspaper said. - 704th, according to Dr. Samuel, does not think. He conducts a search in the "memory" stored on the film, checkers positions, which he met earlier. Then he rejects elections that were bad for him in the past, and makes moves that in the past led to success. ”

It still describes well the concept of “ reinforcement learning, ” one of the MO technologies that has revived the field of AI in recent years. One of the authors of the book on this topic, "Reinforcement Learning," Rich Sutton, called Samuel's research "the earliest" of works, "today considered as directly related" to the modern development of AI. Sutton is also listed among Schaeffer's colleagues at the University of Alberta, where, according to a recent announcement, Google's DeepMind AI laboratory will open its first international research center .

And although his technology was revolutionary, in 10 years Samuel, in his own words, made "limited progress", although he continued to work on it at IBM, looking at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and then receiving a grant from the Department of Defense at Stanford University. As is the case with many of today's unusual AI technologies, he simply did not have enough computing power or data sets for his great ideas to work.

So when Schaeffer began creating his own software, he returned to working for Samuel and found that he could not follow this path. He had to do everything from scratch. At first they called the project "The Beast", but as a result they came to the name "Shinuk", which are called warm winds blowing in the Canadian province of Alberta.

The work captured Schaeffer. As he described it in the book of 1997: “Sometimes, when it was difficult for me to fall asleep, I imagined an excitement that would sweep me when Shinuk finally defeated Terrible Tinsley.” His wife interrupted his reverie with the words: “Do you think about him there again?”

Over the years, the program has grown, retaining two key components. The first one is easy to understand - this is a “book” of complete calculations of all possible positions in checkers with a certain, small number of checkers on the board. So, if there are only six checkers left on the board - and as time went on they got to seven, and then to eight - all possible combinations became known to Schaeffer's software. At the beginning of the 90s, these calculations required huge computational powers for those times.

But the more calculations Schaeffer did with the team, the better Shinuk became. He had the opportunity to win against people. But they knew that they were not able to calculate all possible positions.

Checkers rules are simple [American - approx. transl.], but the number of potential moves is huge - 5 x 10 20 . Schaeffer has a good analogy that helps to present the absurdity of the situation: imagine that we have drained the Pacific Ocean, and now we need to fill it with a small cup. Then it just happens that the whole ocean is the number of possible positions.

The second component of the system is harder to understand. Shinuk had to be able to look for possible moves, starting from the beginning of the match. Like many similar programs, Shinuk looks forward to a multitude of moves and tries to calculate the desirability of each option. At first, Shinuk could look only 14-15 moves ahead, but with the improvement of computers and software, he looked further and further. “As with chess, deeper always means better,” says Scheffer.

In the late 1990s, the American Drafts Federation allowed Shinuka to play in the American Championship. ON did not know defeat and played with Tinsley in a draw six times. This earned the right for software to compete against Tinsley in the world championship.

After the performance, "Shinuka" Tinsley called Jonathan Schaeffer and asked if he could play some friendly matches.

* * *

From 1950 to 1990, Tinsley was the world drafts champion every time he was interested. Sometimes he was removed with the aim of working on mathematics or studying questions of religion, but as a result he came back, beat everyone and again became a champion. For 40 years in total, he lost five games and never left the match.

Derek Oldbury, possibly the second best player of all time, wrote an encyclopedia of checkers. In it, he unceasingly sang the masters: "Marion Tinsley in drafts is like Leonardo da Vinci in science, like Michelangelo in art, like Beethoven in music."

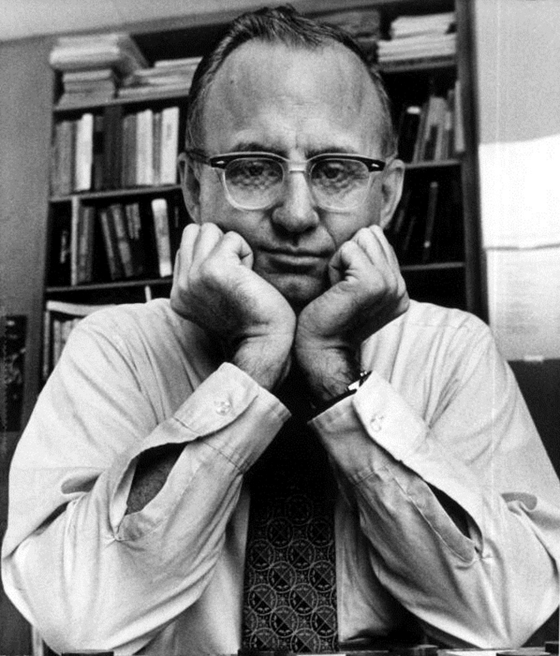

Marion Tinsley, 1974

It is difficult to evaluate Tinsley from the perspective of the 21st century. He seems to be a stranger from another world, or from another time. His life consisted of checkers, mathematics and faith. He was kind, but the style of his game was ruthless and aggressive.

It is often said that someone “lived by reason”, but in the case of Tinsley both life and mind were unusual. For years, first as a student and then as a graduate student at Ohio State University, he spent eight hours a day at checkers. He was never married. “I have never seen marriage and drafts get along, ” he told the reporter . “A rare woman can marry a real checker.” His mother lived with him until the 1980s. In 1993, The Philadelphia Inquirer described Tinsley’s clothing as a big blue sweater worn over a shirt and tie. Lunch served him a "jug of milk, half an apple and a peanut butter sandwich."

His attitude towards the racial issues of the South was also surprising. “I was thinking of going to Africa and becoming a missionary,” he told Sports Illustrated magazine in 1992, “and then some black woman with a long tongue told me that most people who wanted to help black in Africa did not even talk to black in America ".

As a result, he became a priest in a predominantly Negro church and quit his job at the math department at Florida State University to teach at the historically Negro Florida University of Agriculture and Engineering. He spent 26 years there. The photo album, dated one of the last years of his work there, shows the rich life of the student campus, in which Tinsley was probably the only white person over 40. There were no student opinions about his professor, the drafts champion, but his colleague described local obituary: "At the dinner in honor of the resignation, literally everything: old, young, black, white, students, employees of the institute ... told how he influenced their lives." For a man of his time, who grew up in pieces. Kentucky, his life path looks quite amazing.

One thing is clear: Tinsley was a genius. His genius was honed and decorated in something strange and wonderful. He was the best in this one area, and average in everything else. One part of it became similar to AI — highly specialized, but extremely skillful — and all the rest lived a simple human life.

When in 1993, a reporter visited him in Tallahassee, he saw on his site a path leading to a two-story brick house framed by lavender azaleas. In the room on the second floor there was a checkerboard and read books on the checkers. Tinsley loved to sit in a La-Z-Boy velor armchair. He could not explain what the checkers meant for him - why he had studied the sequence of moves all his life, why he kept a magnetic board next to the bed for working out new combinations. It was something close to the divine.

“Checkers is a deep, simple, elegant game,” he said once. And on another occasion, he noted that playing with another good player is similar to how "two artists working together on a work of art."

There is also his most popular quote: "Chess is like watching a huge endless ocean, and checkers are like looking into a bottomless well."

As if the moves in drafts for him were quotations from Holy Scripture, over which he could meditate endlessly and re-understand. “Suddenly an improvement in the published game might have come to mind from nowhere, as if the subconscious were working on it, ” he said of the Chicago Tribune in 1985. - A lot of my discoveries appear in this way, from nowhere. Some of my insights concerning Scripture appear in the same way. ”

* * *

When Tinsley came to Edmonton in 1991 to have friendly matches with Shinuk, Schaeffer was amazed that the world champion agreed to play with his computer just for fun.

Two men settled in his office and the matches began. Schaeffer went for "Shinuka", and entered the moves into the system. The first nine games ended in a draw. In the tenth game, "Shinuk" worked, as usual, tracking moves 16-17 steps forward. He made a move in which he should have had a slight advantage. “Tinsley immediately said: 'You will regret this,'” says Schaeffer. “At that time, I was thinking where he damn it knows what could go wrong?” But in fact, from that moment on, Tinsley began to win. “In his notes about this game, he later wrote that he had foreseen all the moves until the very end of the game and knew that he would win,” wrote Schaeffer.

This moment is sunk into the memory of the programmer. After the match, he ran simulations to understand what went wrong. He found that from that turn to the end of the game, if both sides played perfectly, the computer would still lose. And his next discovery stunned him: in order to understand this, a computer or person would have to calculate 64 moves ahead.

“I was just shocked,” Schaeffer told me. “How can you compete with someone whose understanding of the game is so deep that he immediately, thanks to experience or knowledge or some amazing search, that he will win?”

Sheffer is still trying to understand the incredible ability of Tinsley. When he wrote his book about this story, “One Jump Ahead” [One Jump Ahead], he received a letter from the professor who supervised Tinsley during his studies. According to Schaeffer, it was written there that “he was an exceptionally talented person and capable of one brilliant thing. And it was not checkers, he probably would have been a brilliant mathematician. "

When a person is not motivated by fame or money, we apparently need some explanation of his higher-level actions, the search for some kind of emotional engine that everyone else does not have. Best of all, Tinsley described his motivation in a 1993 Philadelphia Inquirer article. He was an introvert who “did not feel the love” of his parents, who he believed were focused on his sister. To win their approval, he participated in math and spelling competitions. "And, like a crooked but growing branch, I grew up and continued to feel the same way."

* * *

The need to be exceptional inspired Tinsley to attend college at 15, where he met with a passion that would dominate his life. He won his first international title in 1955.

And in 1992, he agreed to put his title of champion in the first international championship of people and cars against Shinuk at stake. The match, held in London, was sponsored by Silicon Graphics. “I can win,” said Tinsley to The Independent. “My programmer was better than Shinuk’s. Jonathan had that, and I had the Lord. ”

Two weeks before this event, another world-class player, Don Lafferty, trained with him in Tallahassee, discussing matches and reviewing positions until late at night.

The 1992 games were held at the Park Lane Hotel, where the international chess championships were held, as well as the computer Olympiad, which debuted Shinuka two years ago. The room was large and two-story, with a balcony from which players could be seen, and with a computer the size of a refrigerator on which Shinuk worked.

, . , «» . «» – 40 .

, . « – , – , – , „“ , , , – ». , , , .

«» 16- . . , – . .

, . «» - , - . « , , – . – , ».

«» . .

« , , , », – CNN .

* * *

1994 .

«» . . «» . «» . , – . – , , !"

. , , . . , , .

, , , . « , . , . , , – . – , , . -, , , ».

, , , . : « », . , , .

, , , . , . , . « » 1997, .

1997 2001 , , , . . .

, – «» – , . 39 .

«», , . , . , , , , .

« - BOMB, , – . – . ». . , , .

, . DeepMind. , , .

, . 1990- IBM-, . : . , . , , 1901 , 1990-. , , , .

, 2007- Science, 19 . - , , . 19 300 , , 19 , – , , .

* * *

. , , , - , . , . .

, . , . . « , , , – . – , , ».

. « », – .

: . . – . – , « , 13:11: ». : « , , , » [ – . trans.].

, - , , . , , . , , , . .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/373729/

All Articles