Hurts badly? How modern medicine tries to save us from pain

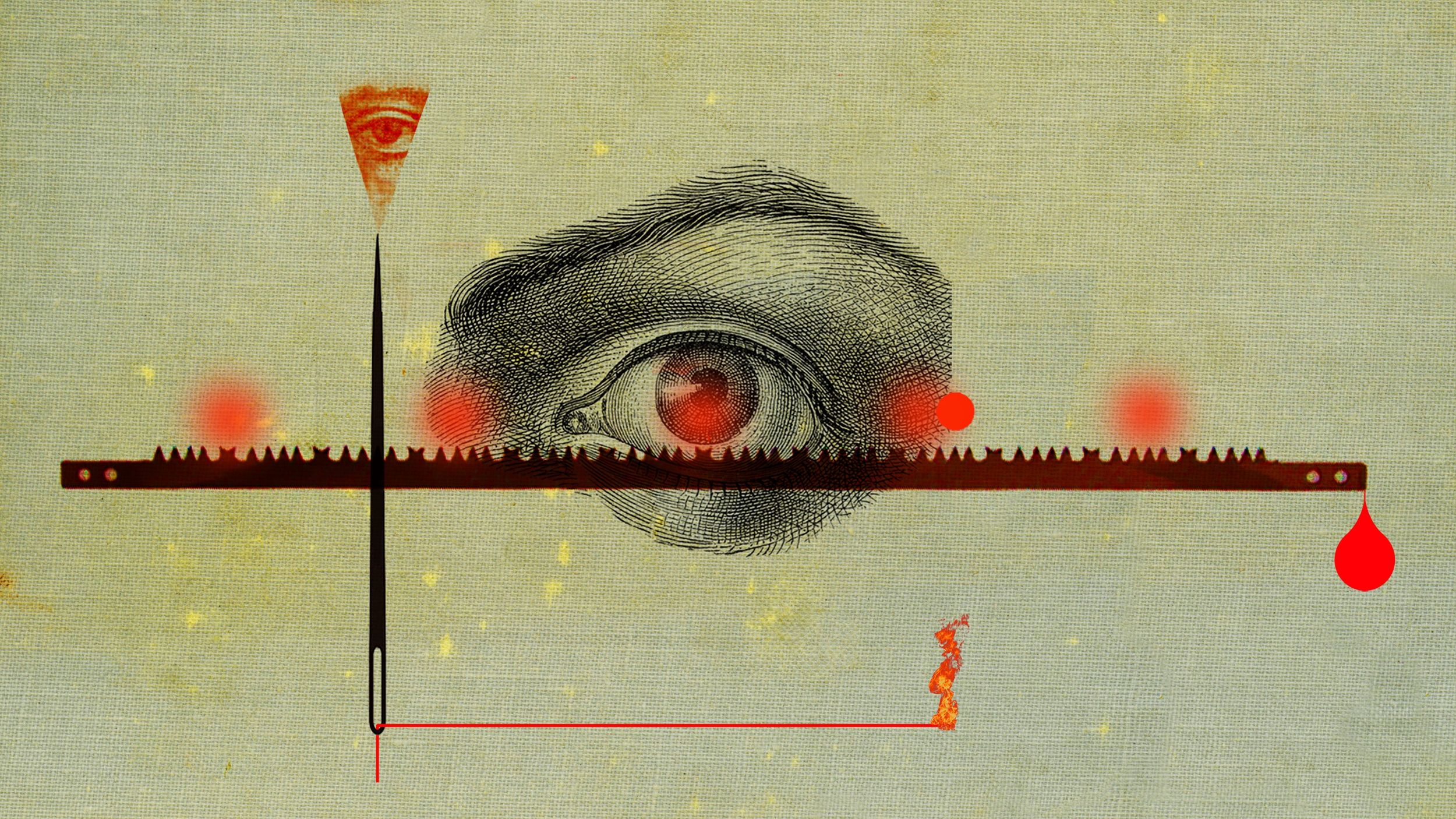

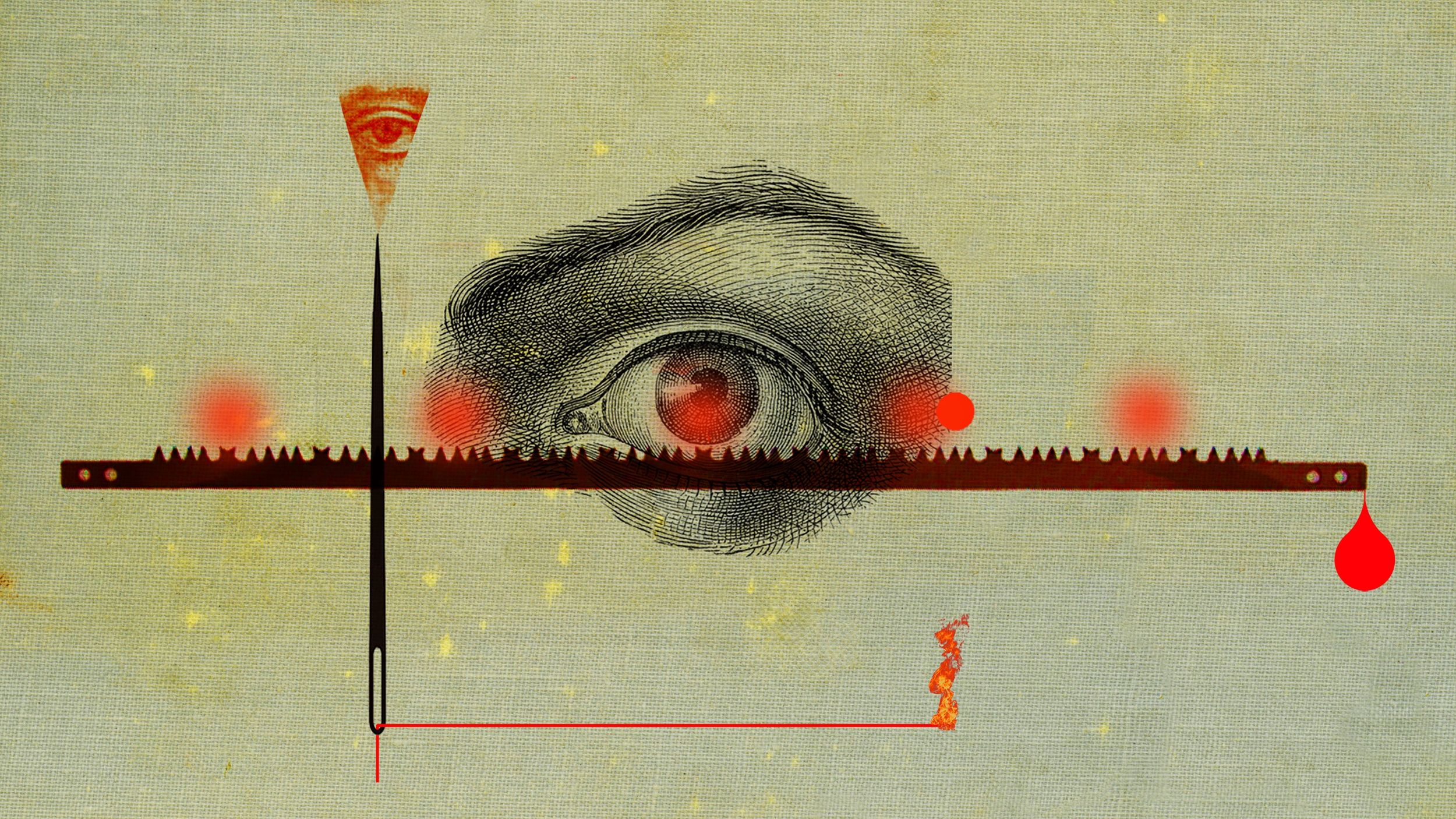

It whines, pulses, burns, painfully hurts ... The pain is difficult to describe and impossible to see. So how do doctors measure it? John Walsh talks about new methods of assessing physical torment.

One night in May, my wife sat up in bed and said, "It hurts me terribly here." She poked her finger in the stomach and made a face. "It feels like something is wrong." In a sleepy state, noting that at that moment it was 2 am, I asked her how it hurts. “It’s like something constantly biting me,” she said.

')

“Hang on,” I said wearily, “help is on.” I brought her ibuprofen tablets and water; she drank it and clung to my hand, waiting for the pain to subside.

An hour later, she was again sitting in bed, extremely agitated. “I felt worse, terribly hurt. Could you call the doctor? ” A miracle happened, and the family doctor answered the call at 3 am, listened to her complaints and concluded, “it could be appendicitis. Did you remove it? ”But she had no operations. “It may be appendicitis,” he concluded, “but in a dangerous case, the pain would be much stronger than you have now. In the morning, go to the hospital, and now take paracetamol and try to sleep. ”

But literally half an hour later, the situation became critical. She awoke again, with a wild pain that made her howl like a witch on a fire. The time of soothing muttering and conjugal procrastination is over. I called a taxi, got into my clothes with difficulty, wrapped her in a bathrobe, and we rushed to St. Mary's hospital in Paddington without something 4 am.

Because of the confusion and distracting affairs, the pain eased a little, and we spent hours in the queue while the doctors dragged us to fill in various forms, measured the pressure and carried out tests. A receptionist poked a needle into his wife's wrist and asked, “is it so painful? And so? And now? ”Before concluding“ you have an impressively high pain threshold. ”

It turned out that the cause of the pain was inflammation of the pancreas, when gallstones came out of the gallbladder and, in the manner of escaped prisoners, made their way into the pancreas, causing severe pain. She was prescribed antibiotics, and a month later she had an operation to remove the gallbladder.

“This is a laparoscopy ,” the surgeon said soothingly, “so you will recover very quickly. Some people felt so good that they drove home immediately after the operation. ” But his optimism was premature. My dear wife, with an unusually high pain threshold, had to stay overnight, and she returned only the next day, pumped up with painkillers. When their action passed, it just twisted in pain. Three days later, she called a specialist, only to hear: “Your discomfort is not due to the operation - it is because of the air that has been pumped inside you to separate the organs before the operation.” Like most surgeons, they lost interest immediately after the operation was deemed successful.

In the recovery period, when I watched as she distorted her face and gritted her teeth, and also occasionally screamed, until a combination of ibuprofen and codeine took its effect, I had a few questions. Chief among them: can any doctor competently talk about pain? Comments and suggestions of the family doctor and the surgeon were cautious, generalized, ignorant. Did the doctor have the right to tell my wife that her level of pain does not look like appendicitis, not knowing what pain threshold my wife has? Did he have the right to advise her to stay in bed with the risk of appendicitis to peritonitis? How can surgeons assume that patients will experience only “discomfort” after the operation, if the wife had severe pain - pain, aggravated by the fear that the operation was unsuccessful?

I was also wondering if there are generally accepted terms on which the doctor could understand the pain experienced by the patient. I remembered my father, a therapist who worked in the south of London in the 1960s, always amazed at the colorful descriptions of pain: “As if I were attacked by a stapler,” “as if rabbits were running around my spine,” penis umbrella for cocktails. " Few of these descriptions, he said, corresponded to texts from medical textbooks. And how was he supposed to do? Guessing and writing aspirin?

In the discussion of pain by people there is some kind of abyss. I wanted to find out how in the medical environment they understand pain, what language they use to describe something invisible, what cannot be measured, except by the subjective description of the person suffering from pain, and what cannot be treated except using opium derivatives, originating from in the Middle Ages.

The main clinical method for the study of pain [in English-speaking countries] is the questionnaire for pain questionnaire McGill . It was developed in the 1970s by two scientists, Ronald Melzak and Warren Thorgerson, from McGill University in Canada. The questionnaire is still the main tool for measuring pain in the clinics of the world.

Melzack and his colleague Patrick Wall of St. Thomas’s Hospital in London revived the pain research area in 1965 with their fruitful “gate control theory”, an innovative explanation of how physiology affects body sensation of pain. In 1984, they wrote The Textbook of Pain, the most comprehensive reference in this area of medicine. It was republished five times, and now there are more than 1000 pages.

In the early 1970s, Melzack began collecting words used by patients to describe pain, and classified them into three categories: sensory (including heat, pressure, pulsation), emotional (relating to emotional effects, such as “exhausting”, “nauseous” , “Exhausting” or “frightening”) and evaluative (from “annoying” and “causing inconvenience” to “terrible”, “intolerable” and “painful”).

You do not need to be a linguistic genius to see the shortcomings of this lexical set. Some words in the emotional and evaluative categories are interchangeable. There is no difference between “frightening” and “terrible” or between “tiring” and “annoying”. And in general, all these words are very similar to the complaints of the Duchess about the ball that disappointed them.

But the matrix of Melzak's torment formed the basis of what turned into McGill's pain questionnaire. The patient listens to how the pain descriptions are read to him, and he only needs to clarify whether the spoken word describes his pain, as well as put a rating of effectiveness. The doctor gets a number with which you can evaluate whether the patient is treating or is getting worse.

A more recent option is the Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) from the National Society for Pain Control. Patients are asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 10 the intensity of the pain they experience in the last week.

The problem with this approach is the inaccuracy of assessing feelings on a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is “the most intense pain that can be imagined”. How can a patient present the worst pain and assign a number to his sensation? A middle-class Brit, who has never participated in hostilities, is unlikely to imagine something more terrible than toothache or tennis injury. Women giving birth can evaluate all other sensations after childbirth at 3-4.

I asked my friends what they thought about the most painful sensations. Naturally, they described the worst thing that happened to them. One put gout in first place. He recalled how he lay on the couch, with his foot injured on the pillow, when his aunt, who had been his guest, walked past him. Her chiffon scarf slid off her neck and lightly touched his foot. It was "unbearable agony." The son-in-law put pain in the first place after tooth filling with nerves removed. He said that, unlike back or muscle pain, such pain cannot be eliminated by changing the position. She was "relentless." A friend admitted that because of hemorrhoidectomy, he developed irritable bowel syndrome, as a result of which daytime spasms he feels like "someone fell asleep in my ass pump and violently pumps water there." According to his description, the pain turns out to be "limitless, as if it will not end until I explode." A familiar woman remembered how the border of her husband's pants caught on her thumb and tore out a nail from him. To describe the effect, she used a musical analogy: “I gave birth to a child, I broke my leg - and this I recall, like moaning noises, like cello; and the torn nail responded with excruciating pain, as if a high, deafening screech of psychopathic violins, I had never heard or felt anything like this before. ”

My familiar novelist specializing in the First World War drew my attention to the memoirs of Stuart Cloete “Victorian Son” (1972), in which the author describes the time he spent in a field hospital. He was amazed at the stoicism of the wounded soldiers. “I heard the guys on a stretcher groaning miserably, but they only asked for water or cigarettes. The only exception was a man with a shot through the hand. It seems to me that this is the most painful wound of all, when the tendons of the arm contract and pull the flesh, like a rack. ”

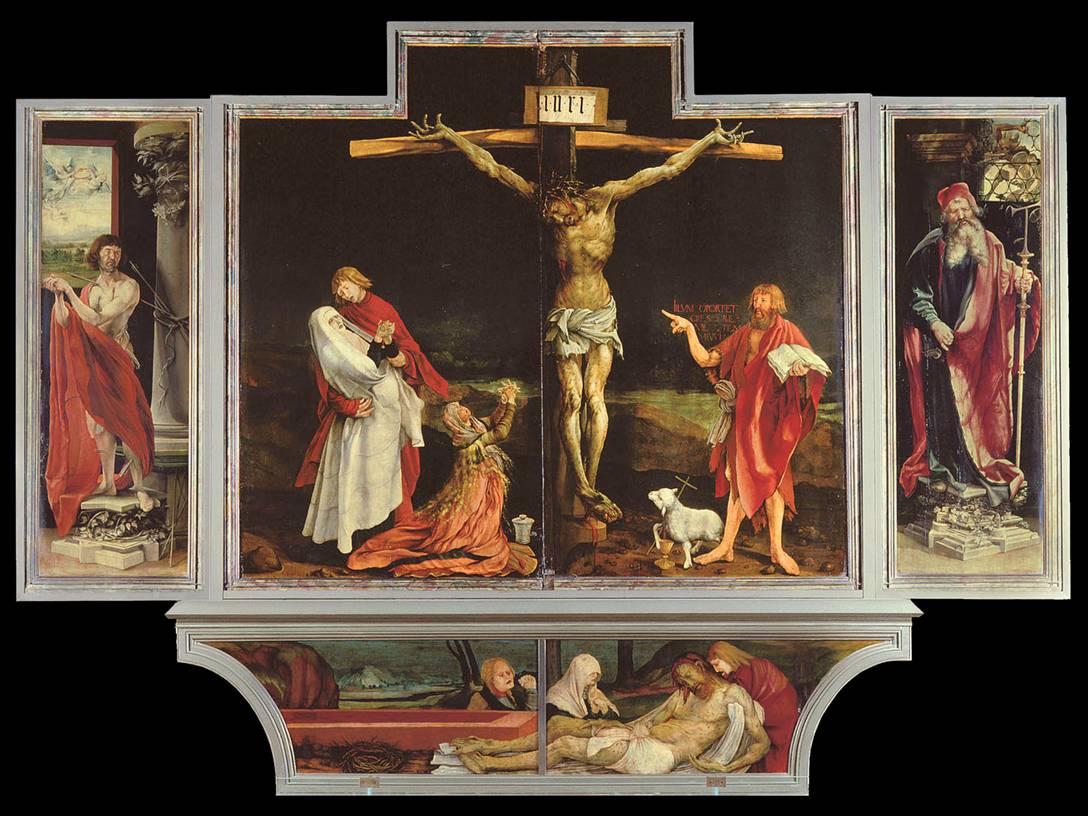

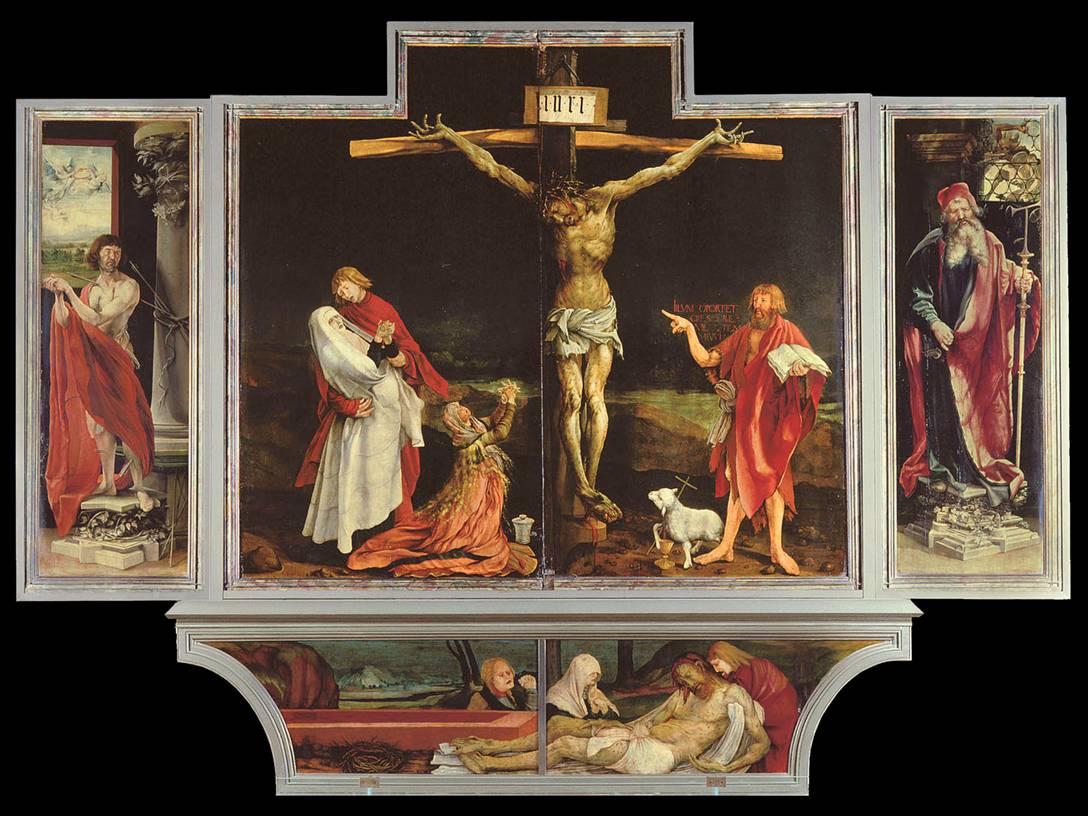

Is it so? Looking at the crucifixion scene in the “Isenheim Altar”, a work by German artist of the Northern Renaissance Matthias Grünewald, written from about 1506 to 1515, you can see how Christ’s fingers tense, twist around the big heads of nails that have nailed his hands to a tree, and believe that this is really a big deal.

It is a pity that such colorful descriptions are reduced in the questionnaire to words like “pulsating” or “acute”, but its task is simply to assign a pain number, which, with a certain luck, will decrease after treatment, when you re-interview the patient.

Such a procedure does not impress Professor Stephen McMahon from the London Pain Consortium, an organization that emerged in 2002 to promote international pain research. “There are a lot of problems when trying to measure pain,” he says. “I think that obsession with numbers is an oversimplification of the problem.” The pain is not one-dimensional. It is not measured on a scale, it has its own “baggage”: how much it threatens, how it affects emotionally, how it affects the possibility of concentration. The obsession with measurements is likely to belong to regulators, who believe that it is necessary to demonstrate effectiveness in order to understand drugs. And in the US Food and Drug Administration, they don’t like the “quality of life” assessment — they like exact numbers. Therefore, we are rejected in positions where it is necessary to assign pains to numbers and count them. The time spent on this is lost because we track only one of the dimensions of pain.

The pain can be acute or chronic, and these words do not mean, as some think, “bad” and “very bad”. “Acute” means a temporary or one-time discomfort, which is usually treated with drugs. Chronic pain persists, you need to live with it, as with a malevolent companion. But due to the fact that patients develop resistance to drugs, it is necessary to look for other types of treatment.

The Control and Neuromodulation Center for Pain at Guy and St. Thomas Hospital in central London is the largest pain study center in Europe. The team is headed by Dr. Adnan Al-Casey, who studied medicine at the University of Basrah in Iraq, and then worked as an anesthesiologist at specialized centers in England, the United States and Canada.

Who are his patients and what kind of pain do they usually suffer from? “I would say that 55-60% of patients suffer from lower back pain,” he says. - The reason is that we do not pay attention to the requests put forward by our lives, how we sit, stand, walk, etc. We spend hours sitting at the computer, and the body pushes heavily on the small joints in the back. ” Al-Casey believes that in Britain the number of cases of chronic back pain has greatly increased over the last 15–20 years, and that “the cost, recalculated for lost working time, is £ 6–7 billion”.

In addition, the clinic treats other types of pain, from chronic headaches to injuries from accidents affecting the nervous system.

Are they still using McGill's questionnaire? “Unfortunately, yes,” says Al-Casey. - This is a subjective measurement. But the pain may worsen due to family quarrels or problems at work, so we find out the details of the patient's life - how they sleep, how they walk and stand, their appetite. The question is not only in his condition, but also in his surroundings. "

The task is to convert the received information into scientific data. “We are working with Professor Raymond Lee, Chairman of the Department of Biomechanics at South Bank University, trying to develop an objective measurement of the patient’s inoperability due to pain,” he says. - They are trying to develop a tool, something like an accelerometer, which gives an accurate idea of the patient's activity or inoperability, and determine the cause of the pain by the way they sit or stand. We are trying to get away from the practice of simply interviewing patients about their pain. ”

For some arriving patients, pain is much more serious than pain in the lower back, and requires special treatment. Al-Casey describes the patient — let's call him Carter — who suffered from terrible inguinal-inguinal nerve neuralgia. In this state, the patient feels a burning sensation and a stinging pain in the groin. “He underwent an operation on the testicles and cut this nerve. The pain was excruciating: when he arrived, he took 4-5 types of drugs, large doses of opiates, anticonvulsants, opium patches, plus paracetamol and ibuprofen. His whole life turned upside down, work was under threat. " Seriously ill Carter was one of the successes of Al-Casey.

Since 2010, the Guy and St. Thomas Hospital in central London offers a course of treatment for those patients whose pain has not been cured in other clinics. Patients arrive for 4 weeks, are out of the ordinary environment, and are examined by a motley company of psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational health specialists, and medical specialists who develop pain management strategies for them.

Many strategies use “neuromodulation”, a term often found in the circles of pain professionals. Simply put, it is a distraction of the brain from the constant processing of pain signals it receives from the “periphery” of the body. Sometimes a distraction is skillfully conducted electric shock therapy.

"We became the first center in the world to use spinal cord stimulation," Al-Casey proudly reports. - With pain, hyperactive nerves send impulses from the periphery to the spinal cord, and from there to the brain that registers the pain. We are trying to send small electrical impulses to the spinal cord by inserting a conductor into the epidural region . The voltage reaches only 1-2 V, so the patient feels a slight tickling instead of pain. After two weeks, we equip the patient with a remote-controlled battery so that he can turn it on when he feels the pain, and continue to go about his business. It is something like a pacemaker that suppresses the increased excitability of the nerves through subthreshold stimulation. The patient only feels a decrease in pain. The operation is non-invasive - we usually send patients home the same day. "

When Carter, a friend with pain in his groin, was unable to help other methods of treatment, Al-Casey turned to his unique methods. “In his case, we used spinal ganglion stimulation. This is something like a small junction box, located under one of the bones of the spine. It overexerts the spinal cord and sends impulses to it and to the brain. I tried innovative technology, placing a small wire in the ganglion, connected to external power supply. For 10 days, the intensity of pain decreased by 70%, according to the patient's own feelings. He wrote me a very nice e-mail about how I changed his life, how the pain passed and how he returns to normal life. He said that his work was saved, as was his family, and he wants to return to sports activities. I wrote to him: "Do not rush, you do not need to immediately climb the Himalayas," - says happily Al-Casey. - This is a terrific result. Other therapies will not give this. ”

The largest of the recent breakthroughs in pain assessment, according to Professor Irene Tracy, head of the clinical neuroscience department at Oxford University, made it clear that chronic pain is a special phenomenon that exists apart from other symptoms. She explains it this way: “We always thought it was just long-lasting acute pain - and if chronic pain is just long-term acute, let's just repair what causes acute pain, and then the chronic will go away. This approach failed miserably. Now we think that chronic pain is a shift to another area, with other mechanisms, such as changes in gene expression, production of chemical compounds, neurophysiology. We have a completely new methods for assessing chronic pain. This is a paradigm shift in pain management. ”

In some media, Tracy is called the "Queen of Pain." . , . , : , , 50 , . « » : « , 10 10 . - ». ? « : ', – 10 ' ».

, , « », , . « . , , , – . , , „ , “, „ “, „ “.

, . „ , , , , , , – . : “ », , . - , , . «, , , ». – , , ".

, , , . . « , , , . , , - . , , ».

. « ,- . – . , , , , , ».

, , – , -. « , . , . . , , . , , , . , . , .

, , „ , , “. , , . , - .

, . 1995 , [Martin Angst; angst (.) – , , , ] . . ( , [Martha Tingle; tingle (.) – , , ]) , , , .

. 100 , , – .

– , , , . . $10 , . – , , - . , .

400 , , , . ( , ), . ; ; ( ) .

, ( ), . – , , .. – , , . -, .

: , , , , . . CHOIR — Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry [ ]. 15000 , 54000 40000 .

– [Sean Mackey], , . , (APS). , , - , . .

» 2008 . . . , . , : ' , '. , , , . , . , ' , – , , , '. - , ' ?'. , ', '. , , , 80% , , ".

. ? «. , , ' 2016 , 2020-.' , , . . . ' '. , , ».

. « , – . „“, „nocere“, „ “. , , . – , , , , . – , , , . , , ».

CHOIR – , – , « », - , « ». , – , , .

« , , , , , . , , : , , , , . – , , ».

, («, 9 »), . « , . , , . , . , , , , ».

« - . – , , ». . , , . « , , ' . '. . , . ». , .

One night in May, my wife sat up in bed and said, "It hurts me terribly here." She poked her finger in the stomach and made a face. "It feels like something is wrong." In a sleepy state, noting that at that moment it was 2 am, I asked her how it hurts. “It’s like something constantly biting me,” she said.

')

“Hang on,” I said wearily, “help is on.” I brought her ibuprofen tablets and water; she drank it and clung to my hand, waiting for the pain to subside.

An hour later, she was again sitting in bed, extremely agitated. “I felt worse, terribly hurt. Could you call the doctor? ” A miracle happened, and the family doctor answered the call at 3 am, listened to her complaints and concluded, “it could be appendicitis. Did you remove it? ”But she had no operations. “It may be appendicitis,” he concluded, “but in a dangerous case, the pain would be much stronger than you have now. In the morning, go to the hospital, and now take paracetamol and try to sleep. ”

But literally half an hour later, the situation became critical. She awoke again, with a wild pain that made her howl like a witch on a fire. The time of soothing muttering and conjugal procrastination is over. I called a taxi, got into my clothes with difficulty, wrapped her in a bathrobe, and we rushed to St. Mary's hospital in Paddington without something 4 am.

Because of the confusion and distracting affairs, the pain eased a little, and we spent hours in the queue while the doctors dragged us to fill in various forms, measured the pressure and carried out tests. A receptionist poked a needle into his wife's wrist and asked, “is it so painful? And so? And now? ”Before concluding“ you have an impressively high pain threshold. ”

It turned out that the cause of the pain was inflammation of the pancreas, when gallstones came out of the gallbladder and, in the manner of escaped prisoners, made their way into the pancreas, causing severe pain. She was prescribed antibiotics, and a month later she had an operation to remove the gallbladder.

“This is a laparoscopy ,” the surgeon said soothingly, “so you will recover very quickly. Some people felt so good that they drove home immediately after the operation. ” But his optimism was premature. My dear wife, with an unusually high pain threshold, had to stay overnight, and she returned only the next day, pumped up with painkillers. When their action passed, it just twisted in pain. Three days later, she called a specialist, only to hear: “Your discomfort is not due to the operation - it is because of the air that has been pumped inside you to separate the organs before the operation.” Like most surgeons, they lost interest immediately after the operation was deemed successful.

In the recovery period, when I watched as she distorted her face and gritted her teeth, and also occasionally screamed, until a combination of ibuprofen and codeine took its effect, I had a few questions. Chief among them: can any doctor competently talk about pain? Comments and suggestions of the family doctor and the surgeon were cautious, generalized, ignorant. Did the doctor have the right to tell my wife that her level of pain does not look like appendicitis, not knowing what pain threshold my wife has? Did he have the right to advise her to stay in bed with the risk of appendicitis to peritonitis? How can surgeons assume that patients will experience only “discomfort” after the operation, if the wife had severe pain - pain, aggravated by the fear that the operation was unsuccessful?

I was also wondering if there are generally accepted terms on which the doctor could understand the pain experienced by the patient. I remembered my father, a therapist who worked in the south of London in the 1960s, always amazed at the colorful descriptions of pain: “As if I were attacked by a stapler,” “as if rabbits were running around my spine,” penis umbrella for cocktails. " Few of these descriptions, he said, corresponded to texts from medical textbooks. And how was he supposed to do? Guessing and writing aspirin?

In the discussion of pain by people there is some kind of abyss. I wanted to find out how in the medical environment they understand pain, what language they use to describe something invisible, what cannot be measured, except by the subjective description of the person suffering from pain, and what cannot be treated except using opium derivatives, originating from in the Middle Ages.

The main clinical method for the study of pain [in English-speaking countries] is the questionnaire for pain questionnaire McGill . It was developed in the 1970s by two scientists, Ronald Melzak and Warren Thorgerson, from McGill University in Canada. The questionnaire is still the main tool for measuring pain in the clinics of the world.

Melzack and his colleague Patrick Wall of St. Thomas’s Hospital in London revived the pain research area in 1965 with their fruitful “gate control theory”, an innovative explanation of how physiology affects body sensation of pain. In 1984, they wrote The Textbook of Pain, the most comprehensive reference in this area of medicine. It was republished five times, and now there are more than 1000 pages.

In the early 1970s, Melzack began collecting words used by patients to describe pain, and classified them into three categories: sensory (including heat, pressure, pulsation), emotional (relating to emotional effects, such as “exhausting”, “nauseous” , “Exhausting” or “frightening”) and evaluative (from “annoying” and “causing inconvenience” to “terrible”, “intolerable” and “painful”).

You do not need to be a linguistic genius to see the shortcomings of this lexical set. Some words in the emotional and evaluative categories are interchangeable. There is no difference between “frightening” and “terrible” or between “tiring” and “annoying”. And in general, all these words are very similar to the complaints of the Duchess about the ball that disappointed them.

But the matrix of Melzak's torment formed the basis of what turned into McGill's pain questionnaire. The patient listens to how the pain descriptions are read to him, and he only needs to clarify whether the spoken word describes his pain, as well as put a rating of effectiveness. The doctor gets a number with which you can evaluate whether the patient is treating or is getting worse.

A more recent option is the Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) from the National Society for Pain Control. Patients are asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 10 the intensity of the pain they experience in the last week.

The problem with this approach is the inaccuracy of assessing feelings on a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is “the most intense pain that can be imagined”. How can a patient present the worst pain and assign a number to his sensation? A middle-class Brit, who has never participated in hostilities, is unlikely to imagine something more terrible than toothache or tennis injury. Women giving birth can evaluate all other sensations after childbirth at 3-4.

I asked my friends what they thought about the most painful sensations. Naturally, they described the worst thing that happened to them. One put gout in first place. He recalled how he lay on the couch, with his foot injured on the pillow, when his aunt, who had been his guest, walked past him. Her chiffon scarf slid off her neck and lightly touched his foot. It was "unbearable agony." The son-in-law put pain in the first place after tooth filling with nerves removed. He said that, unlike back or muscle pain, such pain cannot be eliminated by changing the position. She was "relentless." A friend admitted that because of hemorrhoidectomy, he developed irritable bowel syndrome, as a result of which daytime spasms he feels like "someone fell asleep in my ass pump and violently pumps water there." According to his description, the pain turns out to be "limitless, as if it will not end until I explode." A familiar woman remembered how the border of her husband's pants caught on her thumb and tore out a nail from him. To describe the effect, she used a musical analogy: “I gave birth to a child, I broke my leg - and this I recall, like moaning noises, like cello; and the torn nail responded with excruciating pain, as if a high, deafening screech of psychopathic violins, I had never heard or felt anything like this before. ”

My familiar novelist specializing in the First World War drew my attention to the memoirs of Stuart Cloete “Victorian Son” (1972), in which the author describes the time he spent in a field hospital. He was amazed at the stoicism of the wounded soldiers. “I heard the guys on a stretcher groaning miserably, but they only asked for water or cigarettes. The only exception was a man with a shot through the hand. It seems to me that this is the most painful wound of all, when the tendons of the arm contract and pull the flesh, like a rack. ”

Is it so? Looking at the crucifixion scene in the “Isenheim Altar”, a work by German artist of the Northern Renaissance Matthias Grünewald, written from about 1506 to 1515, you can see how Christ’s fingers tense, twist around the big heads of nails that have nailed his hands to a tree, and believe that this is really a big deal.

It is a pity that such colorful descriptions are reduced in the questionnaire to words like “pulsating” or “acute”, but its task is simply to assign a pain number, which, with a certain luck, will decrease after treatment, when you re-interview the patient.

Such a procedure does not impress Professor Stephen McMahon from the London Pain Consortium, an organization that emerged in 2002 to promote international pain research. “There are a lot of problems when trying to measure pain,” he says. “I think that obsession with numbers is an oversimplification of the problem.” The pain is not one-dimensional. It is not measured on a scale, it has its own “baggage”: how much it threatens, how it affects emotionally, how it affects the possibility of concentration. The obsession with measurements is likely to belong to regulators, who believe that it is necessary to demonstrate effectiveness in order to understand drugs. And in the US Food and Drug Administration, they don’t like the “quality of life” assessment — they like exact numbers. Therefore, we are rejected in positions where it is necessary to assign pains to numbers and count them. The time spent on this is lost because we track only one of the dimensions of pain.

The pain can be acute or chronic, and these words do not mean, as some think, “bad” and “very bad”. “Acute” means a temporary or one-time discomfort, which is usually treated with drugs. Chronic pain persists, you need to live with it, as with a malevolent companion. But due to the fact that patients develop resistance to drugs, it is necessary to look for other types of treatment.

The Control and Neuromodulation Center for Pain at Guy and St. Thomas Hospital in central London is the largest pain study center in Europe. The team is headed by Dr. Adnan Al-Casey, who studied medicine at the University of Basrah in Iraq, and then worked as an anesthesiologist at specialized centers in England, the United States and Canada.

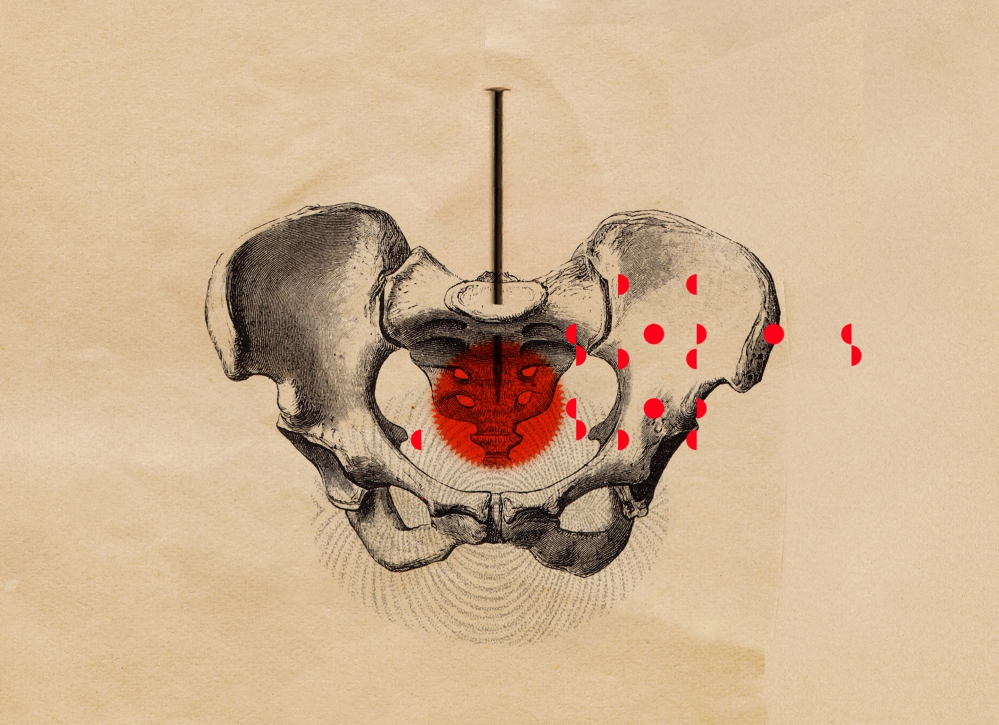

Who are his patients and what kind of pain do they usually suffer from? “I would say that 55-60% of patients suffer from lower back pain,” he says. - The reason is that we do not pay attention to the requests put forward by our lives, how we sit, stand, walk, etc. We spend hours sitting at the computer, and the body pushes heavily on the small joints in the back. ” Al-Casey believes that in Britain the number of cases of chronic back pain has greatly increased over the last 15–20 years, and that “the cost, recalculated for lost working time, is £ 6–7 billion”.

In addition, the clinic treats other types of pain, from chronic headaches to injuries from accidents affecting the nervous system.

Are they still using McGill's questionnaire? “Unfortunately, yes,” says Al-Casey. - This is a subjective measurement. But the pain may worsen due to family quarrels or problems at work, so we find out the details of the patient's life - how they sleep, how they walk and stand, their appetite. The question is not only in his condition, but also in his surroundings. "

The task is to convert the received information into scientific data. “We are working with Professor Raymond Lee, Chairman of the Department of Biomechanics at South Bank University, trying to develop an objective measurement of the patient’s inoperability due to pain,” he says. - They are trying to develop a tool, something like an accelerometer, which gives an accurate idea of the patient's activity or inoperability, and determine the cause of the pain by the way they sit or stand. We are trying to get away from the practice of simply interviewing patients about their pain. ”

For some arriving patients, pain is much more serious than pain in the lower back, and requires special treatment. Al-Casey describes the patient — let's call him Carter — who suffered from terrible inguinal-inguinal nerve neuralgia. In this state, the patient feels a burning sensation and a stinging pain in the groin. “He underwent an operation on the testicles and cut this nerve. The pain was excruciating: when he arrived, he took 4-5 types of drugs, large doses of opiates, anticonvulsants, opium patches, plus paracetamol and ibuprofen. His whole life turned upside down, work was under threat. " Seriously ill Carter was one of the successes of Al-Casey.

Since 2010, the Guy and St. Thomas Hospital in central London offers a course of treatment for those patients whose pain has not been cured in other clinics. Patients arrive for 4 weeks, are out of the ordinary environment, and are examined by a motley company of psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational health specialists, and medical specialists who develop pain management strategies for them.

Many strategies use “neuromodulation”, a term often found in the circles of pain professionals. Simply put, it is a distraction of the brain from the constant processing of pain signals it receives from the “periphery” of the body. Sometimes a distraction is skillfully conducted electric shock therapy.

"We became the first center in the world to use spinal cord stimulation," Al-Casey proudly reports. - With pain, hyperactive nerves send impulses from the periphery to the spinal cord, and from there to the brain that registers the pain. We are trying to send small electrical impulses to the spinal cord by inserting a conductor into the epidural region . The voltage reaches only 1-2 V, so the patient feels a slight tickling instead of pain. After two weeks, we equip the patient with a remote-controlled battery so that he can turn it on when he feels the pain, and continue to go about his business. It is something like a pacemaker that suppresses the increased excitability of the nerves through subthreshold stimulation. The patient only feels a decrease in pain. The operation is non-invasive - we usually send patients home the same day. "

When Carter, a friend with pain in his groin, was unable to help other methods of treatment, Al-Casey turned to his unique methods. “In his case, we used spinal ganglion stimulation. This is something like a small junction box, located under one of the bones of the spine. It overexerts the spinal cord and sends impulses to it and to the brain. I tried innovative technology, placing a small wire in the ganglion, connected to external power supply. For 10 days, the intensity of pain decreased by 70%, according to the patient's own feelings. He wrote me a very nice e-mail about how I changed his life, how the pain passed and how he returns to normal life. He said that his work was saved, as was his family, and he wants to return to sports activities. I wrote to him: "Do not rush, you do not need to immediately climb the Himalayas," - says happily Al-Casey. - This is a terrific result. Other therapies will not give this. ”

The largest of the recent breakthroughs in pain assessment, according to Professor Irene Tracy, head of the clinical neuroscience department at Oxford University, made it clear that chronic pain is a special phenomenon that exists apart from other symptoms. She explains it this way: “We always thought it was just long-lasting acute pain - and if chronic pain is just long-term acute, let's just repair what causes acute pain, and then the chronic will go away. This approach failed miserably. Now we think that chronic pain is a shift to another area, with other mechanisms, such as changes in gene expression, production of chemical compounds, neurophysiology. We have a completely new methods for assessing chronic pain. This is a paradigm shift in pain management. ”

In some media, Tracy is called the "Queen of Pain." . , . , : , , 50 , . « » : « , 10 10 . - ». ? « : ', – 10 ' ».

, , « », , . « . , , , – . , , „ , “, „ “, „ “.

, . „ , , , , , , – . : “ », , . - , , . «, , , ». – , , ".

, , , . . « , , , . , , - . , , ».

. « ,- . – . , , , , , ».

, , – , -. « , . , . . , , . , , , . , . , .

, , „ , , “. , , . , - .

, . 1995 , [Martin Angst; angst (.) – , , , ] . . ( , [Martha Tingle; tingle (.) – , , ]) , , , .

. 100 , , – .

– , , , . . $10 , . – , , - . , .

400 , , , . ( , ), . ; ; ( ) .

, ( ), . – , , .. – , , . -, .

: , , , , . . CHOIR — Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry [ ]. 15000 , 54000 40000 .

– [Sean Mackey], , . , (APS). , , - , . .

» 2008 . . . , . , : ' , '. , , , . , . , ' , – , , , '. - , ' ?'. , ', '. , , , 80% , , ".

. ? «. , , ' 2016 , 2020-.' , , . . . ' '. , , ».

. « , – . „“, „nocere“, „ “. , , . – , , , , . – , , , . , , ».

CHOIR – , – , « », - , « ». , – , , .

« , , , , , . , , : , , , , . – , , ».

, («, 9 »), . « , . , , . , . , , , , ».

« - . – , , ». . , , . « , , ' . '. . , . ». , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/373069/

All Articles