Linux 25 years

“Hello to all minix users -

“Hello to all minix users -I create a (free) operating system (just a hobby, nothing professional-level gnu) for 386 (486) AT-clones. I have been working with a similar one since April, it will be ready soon. I would like to get any feedback on what you like and dislike in minix, because my OS reminds it a bit (the same physical location of the file system (for practical reasons) among other things).

I have already ported bash (1.08) and gcc (1.40), and everything seems to work. That is, within a few months I will have something practical to use, and I would like to know what features will be needed. All offers are accepted, although I do not promise that I will fulfill them :-)

')

Linus (torvalds@kruuna.helsinki.fi)

Ps. Yes - there is no minix code in it, it has a multi-threaded file system. It is NOT portable (uses task switching 386, etc.), and probably will never support anything other than AT hard drives, but that's all I have :-(. ”

In the late evening of August 25, 1991, Linus Torvalds left this message in the newsgroup

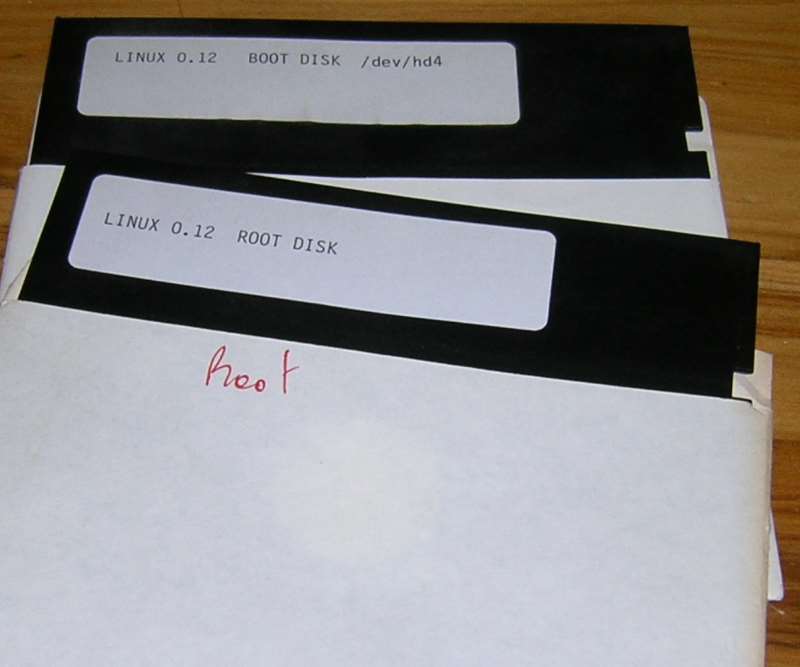

comp.os.minix . Linus at the time was 21 years old, he studied at the University of Helsinki in Finland. 25 years later, the operating system, which Linus writes and tens of thousands more developers , manages the work of billions of devices around the world: from tiny microcontrollers, single-board computers and smartphones to huge supercomputers for thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of cores.On the image: floppy disks on which one of the earliest versions of Linux are written, photo by Simon Rambla .

Unix

If it comes to the internal structure of Linux, then inevitably begins a conversation about compliance with the principles of Unix. Why imitate, why not just use Unix? And what are these standards for? To answer this question you need to dig a little deeper into the end of the sixties.

In 1968–69, uncertainty soared in the air of Bell Labs: the project of the time-sharing operating system Multics (Multiplexed Information and Computing Service) slowly came to a standstill. The new system had to provide time sharing, that is, allow several people to use the machine at the same time. At that time, a common practice was to launch programs one after another.

In the end, American Telephone & Telegraph left a joint project with General Electric and MIT in which millions of dollars were invested over five years. Some of the engineers who worked on Multics — Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Malcolm Douglas McIlroy, Joseph Ossanna — felt the need to continue working on such a project and did not want to lose the cozy working atmosphere that had already formed. The group began work on a new project. On paper were made sketches of the file system and the basics of the operating system. Two facts helped in the work: a PDP-7 mini-computer copy found in the laboratory and Thompson's temporary bachelor status, whose wife went to her parents for a month to show her newborn son.

The very name of the operating system was born from a joke of a colleague who indicated that the OS can support only one user - Thompson. It was logical to consider its Un-multiplexed Information and Computing Service, from which it turned out Unics. The word later became Unix.

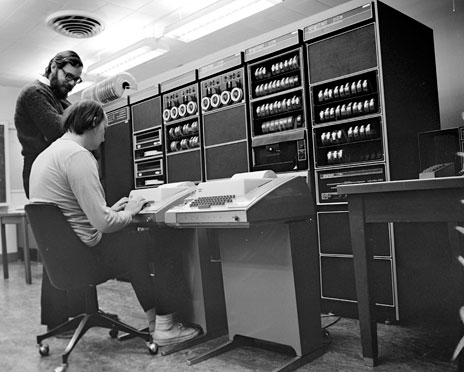

Thompson (sitting) and Ritchie work on the PDP-11, 1972.

Unix has laid down what is today taken for granted. A set of these rules and regulations is called the " Unix philosophy ". Developers write programs that do one thing, but fine. Programs work together and use text flows for communication as a universal interface. The file system supports subdirectories, and individual devices are represented as special files. Not only the principles remained, but also the simplest utilities written for systems without monitors. As part of almost any Unix-like system there is a text editor ed , originally created for working with a teletype.

Over the years, Unix has evolved, new versions have been released, new functions have appeared. The system grew up and began to remind something serious. In 1973–74, the research report was lit up for the outside world. Showered with requests for a copy of the software.

But the fate of the OSes was dictated by the legal status of AT & T. In exchange for a de facto monopoly in the telephone segment, the company was forbidden to sell products not related to telephones and telecommunications. Unix sources were available for a fee, but there was no support. Over the years, presentations of Bell Labs researchers at conferences included a slide with the proud: "No ads, no support, no bug fixes, pay ahead."

Those interested did not consider Unix to be a complete product, since it was pointless to wait for outside help. And the source code helped in fixing bugs. It was possible to get magnets with corrections and share yours in the Usenix group, which was followed by enthusiasm by the enthusiasm. By the mid-1970s, something remotely reminiscent of the modern open source software community was formed.

Linux

The system was rewritten, it developed, other projects sprang from it. One of the Unix clones was Minix. This is the Andrew Tanenbaum training operating system, which he wrote in 1987 to illustrate the textbook Operating Systems: Development and Implementation. And this book fell into the hands of our young student.

There were also reasons for starting work on Linux. The main one is the lack of an adequate free Unix clone at the beginning of 1991. Yes, there was a GNU project. Application programs were written and developed. There were problems only with the Hurd core, which to this day has not reached acceptable stability.

There was also a Berkeley Software Distribution project based on the sixth edition of Unix. But at the beginning of the nineties, BSD was in litigation between AT & T and the University of California. The AT & T code was removed from the project, and the descendants of 386BSD and 4.4BSD-Lite continue to live in the form of OS X, FreeBSD, and a number of other operating systems. The court will end only in January 1994, where later described events. As Linus himself said , if then 386BSD were already available, the Linux project would never have seen the light.

Minix, which fell into the hands of Torvalds, was developed for compatibility with IBM PC microcomputers. Initially, this OS was written on 8088, but later it was ported to Intel 80386. Linus did not burn with a special love for Intel products. Behind him, he had programming experience on the Sinclair QL, the elder brother of the ZX Spectrum, and even earlier he was sitting at the Commodore Vic-20. On these computers, he wrote several programs, for example, a clone of Pac-Man. Partly because of Minix, Torvalds decided to get a “pi-si” typewriter.

Linus lived at home with his mother, so they managed to cut out some money out of a loan for education. After Christmas (which also promised additional money to hand), on January 5, 1991, Torvalds bought a PC with an Intel 386 DX33 processor, 4 MB of RAM and a 40 MB hard drive. Six months later, Linus bought a math coprocessor for floating point operations. He did this solely for the sake of ensuring compatibility of the product being developed, and emulation suited him perfectly.

Minix diskettes came in only a few months. Therefore, the first time Linus was killing time in games like Prince of Persia under MS-DOS. He also studied the processor architecture of his new machine. Torvalds launched two processes, one of which displayed the letter A, the other B. Then Torvalds forced the tasks to switch on a timer. Sequences like AAAA BBBB appeared on the screen. So the first few months were not very productive.

A small experiment with character output was important. Linus understood what he did. He changed two processes so that they behaved like the simplest package of a terminal emulator. One read the input from the keyboard, sent it to the modem, the other read from the modem and sent it to the screen. All this required keyboard, text mode VGA, serial port drivers to receive and read news from the university. About the POSIX standard, which describes the interaction between the operating system and application programs, Torvalds found out in the summer of the same year. Linus continued to work: a disk driver appeared, a file system, an emulation package improved.

If there is an operating system, then it should have a name. The author himself wanted to name the Freax project and half a year kept the files under this name. But, as we know, the name was different. As in the case of Unix, the idea of the name of the operating system was laid not by the author. Ari Lemke, one of the university employees, spoke with Linus. He showed interest in the Torvalds project and allocated a folder on the FTP server of the university

ftp.funet.fi . The path to it sounded like /pub/os/linux . The name of the catalog Lemkke thought up independently, without asking Linus. Though Torvalds was afraid to appear an egoist who sculpts his name for everything, but the name is fixed.Hello, my name is Richard Stallman, and I pronounce Linux as GNU / Linux

I am afraid that a maximum of 64 tasks (and one for the swap planner) no matter how small they are. Such is she fragmentation - it is so controlled. It seems that at the moment 64 MB [memory per process] is more than enough, but 64 tasks are a bit cramped. Probably, I will make the restrictions easily changeable (say, 32 MB / 128 tasks) just by recompiling the kernel. Although I do not envy the one who will cause> 64 processes :-)

Linus

The first versions came out literally for several fans and were distributed under Linus' own license, which prohibited commercial use. The utilities from the GNU project were strung to the rapidly developing but bare core: the C compiler, Bash, etc. Version 0.99 was released in December 1992 and is already licensed under the GNU GPL license.

From the start, Linux was only the core of the system. Key utilities for the job were taken from GNU, which was even reflected in the disputes about the name of the resulting OS .

Today, by the word Linux, people and organizations mean not even this set of GNU utilities and kernels, but a huge family of distributions. For twenty-five years, a huge, it seems even an excess set of assemblies of the same OS has appeared. The free nature of the OS and the huge library of open software allows that anyone can build their system and distribute it.

The Android operating system, which lives on smartphones and tablets, but is sometimes found on the exotic level of smart TVs, also has Linux in its depths. There are many distributions that make up an alternative to Windows and OS X on desktops and laptops. But these are only the most obvious ways for the average person to touch the "penguin" live. Linux manages millions of web servers and a variety of network devices around the world that provide the Internet. Linux can be found in the most unexpected devices: these are medical equipment, smart watches, sensors and the Internet of things, mainframes and supercomputers.

For twenty-five years, the scale of development has changed dramatically. Today Linux writes more than one Torvalds. The whole community of developers makes its own corrections and implements new functions. And some of them are employees of companies whose task sometimes is not only making changes to the core, but also writing application software. Volunteer committers are becoming rare. They are quickly hired by companies , where these people often continue to make the same contribution to the development of the core. Today, independent kernel developers are a real shortage, only 7.7% of them.

Although someone may not like the loss of amateur status, today Linux is a powerful professional open source project that is supported and from which they benefit from a multinational corporation. According to the Linux Foundation , 13,500 developers and 1,300 companies contributed to Git in Linux since being traceable. On average, 7.8 corrections are accepted per hour, that is, 187 changes per day or 1310 per week.

The original kernel version 0.01 consisted of some 10 thousand lines of code. Today, such a volume is written in a few days. 25 years of development efforts around the world have greatly changed the scope and significance of the product, which began as an amateur project of a Finnish student.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/372605/

All Articles