Just about quantum entanglement.

Quantum entanglement is one of the most complex concepts in science, but its basic principles are simple. And if you understand it, entanglement opens the way to a better understanding of such concepts as the multiplicity of worlds in quantum theory.

The concept of quantum entanglement is shrouded in a charming aura of mystery, as well as the (somehow) related requirement of quantum theory about the need for "many worlds." And, nevertheless, in its essence these are scientific ideas with a mundane meaning and concrete applications. I would like to explain the concepts of entanglement and multitude of worlds as simply and clearly as I know them myself.

')

Entanglement is considered a phenomenon unique to quantum mechanics - but it is not. In fact, for a start it will be clearer (although this is an unusual approach) to consider a simple, non-quantum (classical) version of entanglement. This will allow us to separate the subtleties associated with the intricacies themselves from other oddities of quantum theory.

Confusion appears in situations in which we have partial information about the state of the two systems. For example, two objects can become our systems — let's call them kaons. “K” will denote “classic” objects. But if you really want to imagine something specific and pleasant - imagine that these are cakes.

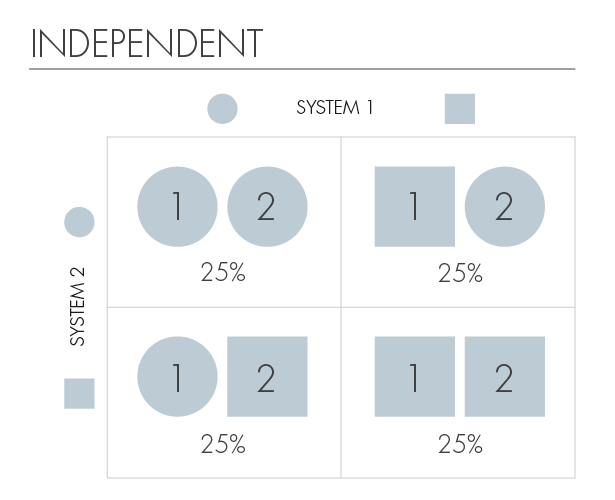

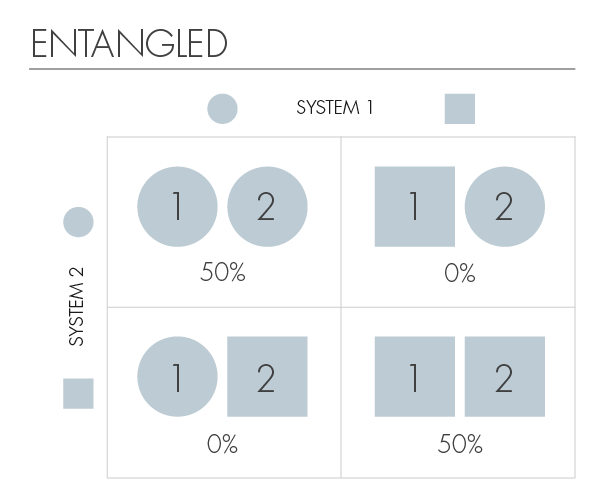

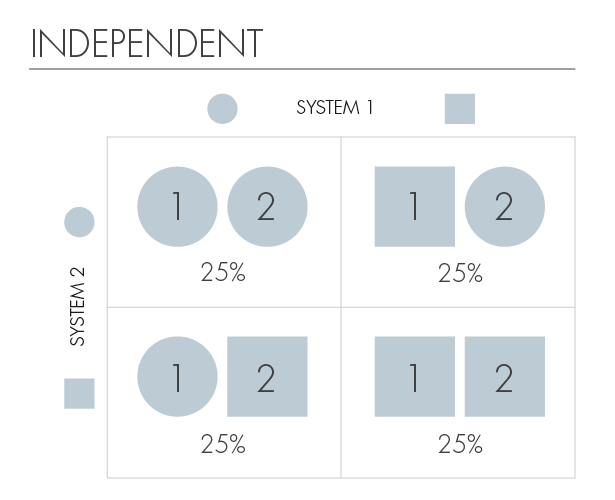

Our kaons will have two shapes, square or round, and these shapes will denote their possible states. Then the four possible joint states of the two kaons will be: (square, square), (square, circle), (circle, square), (circle, circle). The table shows the probability of the system being in one of the four listed states.

We will say that kaons are “independent” if knowledge of the state of one of them does not give us information about the state of the other. And this table has this property. If the first kaon (cake) is square, we still do not know the shape of the second. Conversely, the form of the second does not tell us anything about the form of the first.

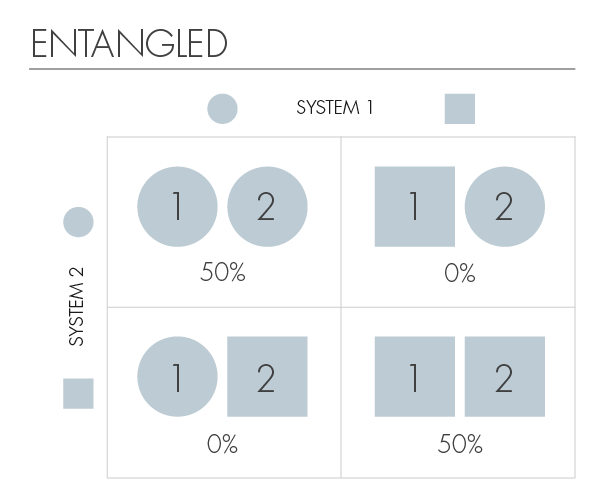

On the other hand, we will say that two kaons are confused if the information about one of them improves our knowledge about the other. The second sign will show us a strong confusion. In this case, if the first kaon is round, we will know that the second one is also round. And if the first kaon is square, then the second one will be the same. Knowing the form of one, we uniquely determine the form of the other.

The quantum version of entanglement looks, in fact, also - this is a lack of independence. In quantum theory, states are described by mathematical objects called the wave function. The rules that combine wave functions with physical capabilities, create very interesting difficulties, which we will discuss later, but the basic concept of intricate knowledge, which we demonstrated for the classical case, remains the same.

Although cakes cannot be considered quantum systems, the entanglement of quantum systems arises naturally — for example, after a collision of particles. In practice, uncontaminated (independent) states can be considered rare exceptions, since the interaction of systems between them leads to correlations.

Consider, for example, molecules. They consist of subsystems - specifically, electrons and nuclei. The minimum energy state of the molecule, in which it is usually located, is a very entangled state of electrons and the nucleus, since the arrangement of these constituent particles will not be independent. When the nucleus moves, the electron moves with it.

Let's return to our example. If we write Φ ■, Φ ● as wave functions describing system 1 in its square or circular states and ψ ■, ψ ● for wave functions describing system 2 in its square or circular states, then in our working example all states can be described , as:

Independent: Φ ■ ■ + Φ ■ ψ ● + Φ ● ■ + Φ ● ●

Entangled: Φ ■ ■ + Φ ● ψ ●

The independent version can also be written as:

(Φ ■ + Φ ●) (ψ ■ + ψ ●)

Note that in the latter case, the brackets clearly divide the first and second systems into independent parts.

There are many ways to create entangled states. One of them is to measure the composite system that gives you partial information. You can find out, for example, that the two systems agreed to be of the same form, without knowing at the same time which form they chose. This concept will become important later.

More characteristic effects of quantum entanglement, such as the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) and Greenberg-Horn-Seilinger (GHZ) effects, arise from its interaction with another property of quantum theory called the complementarity principle. To discuss EPR and GHZ, let me first introduce this principle to you.

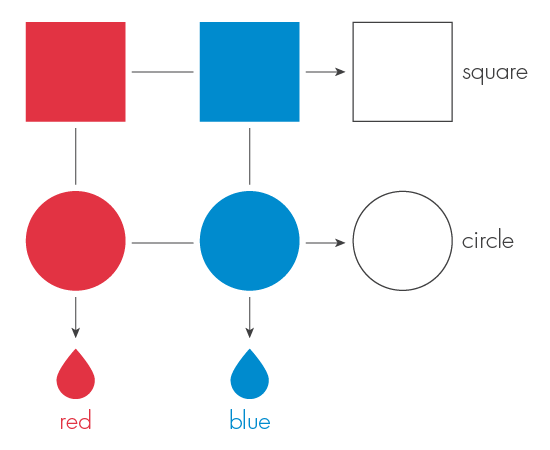

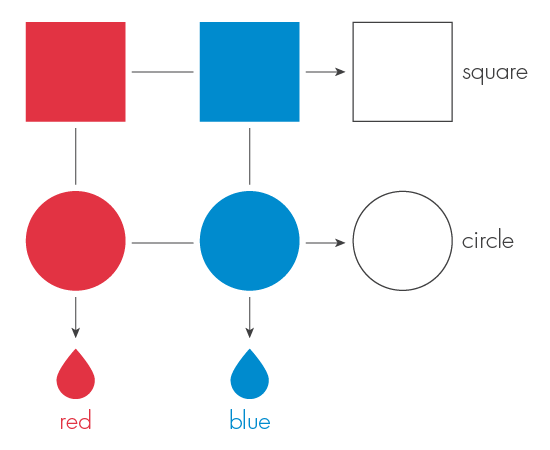

Up to this point, we imagined that kaons come in two forms (square and round). Now imagine that there are two more colors - red and blue. Considering classical systems, for example, cakes, this additional property would mean that a kaon can exist in one of four possible states: a red square, a red circle, a blue square and a blue circle.

But quantum cakes are quantum-like ... Or quantons ... They behave quite differently. The fact that a quanton in some situations may have a different shape and color does not necessarily mean that it simultaneously possesses both form and color. In fact, the common sense that Einstein demanded from physical reality does not match the experimental facts that we will soon see.

We can measure the shape of the quanton, but at the same time we will lose all the information about its color. Or we can measure color, but lose information about its shape. According to quantum theory, we cannot measure both shape and color at the same time. No one’s view of quantum reality is complete; we have to take into account many different and mutually exclusive pictures, each of which has its own incomplete picture of what is happening. This is the essence of the complementarity principle, such as Niels Bohr put it.

As a result, quantum theory forces us to be cautious in attributing to the properties of physical reality. In order to avoid contradictions, we have to admit that:

There is no property if it is not measured.

Measurement is an active process that changes the system being measured.

We now describe two exemplary, but not classical, illustrations of the oddities of quantum theory. Both were tested in rigorous experiments (in real experiments, people measure not the shapes and colors of cakes, but the angular moments of electrons).

Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen (EPR) described a surprising effect when the two quantum systems are entangled. The EPR effect combines a special, experimentally attainable form of quantum entanglement with the principle of complementarity.

An EPR pair consists of two quantons, each of which can measure shape or color (but not both at once). Suppose we have many such pairs, they are all the same, and we can choose which measurements we make over their components. If we measure the shape of one of the members of an EPR pair, we are equally likely to get a square or a circle. If we measure the color, then with equal probability we get red or blue.

Interesting effects, which seemed to be paradoxical to EPR, arise when we measure both members of a pair. When we measure the color of both members, or their shape, we find that the results always coincide. That is, if we find that one of them is red and then measure the color of the second, we also find that it is red — and so on. On the other hand, if we measure the shape of one and the color of another, no correlation is observed. That is, if the first was a square, then the second with the same probability can be blue or red.

According to quantum theory, we will get such results, even if the two systems will share a huge distance and measurements will be carried out almost simultaneously. The choice of the type of measurements in one place, apparently, affects the state of the system in another place. This “frightening long-range”, as Einstein called it, apparently requires the transfer of information - in our case, information about the measurement - with a speed exceeding the speed of light.

But is it? Until I know what result you got, I do not know what to expect me. I get useful information when I know your result, not when you take a measurement. And any message containing the result you received must be transmitted in any physical way, slower than the speed of light.

Upon further study, the paradox breaks down even more. Let's consider the state of the second system, if the measurement of the first gave a red color. If we decide to measure the color of the second quanton, we get red. But by the principle of complementarity, if we decide to measure its shape when it is in the “red” state, we will have equal chances of getting a square or a circle. Therefore, the EPR result is logically predefined. This is simply a retelling of the principle of complementarity.

There is no paradox in the fact that remote events correlate. After all, if we put one of the two gloves from the pair into the boxes and send them to different ends of the planet, it is not surprising that by looking in one box, I can determine which hand the other glove is intended for. Similarly, in all cases, the correlation of EPR pairs must be fixed to them when they are near and therefore they can withstand the subsequent separation, as if having a memory. The strangeness of the EPR paradox is not in itself the possibility of correlation, but in the possibility of its preservation in the form of add-ons.

Daniel Greenberger, Michael Horn and Anton Zeilinger opened another excellent example of quantum entanglement. It includes our three quantons, which are in a specially prepared entangled state (GHZ-state). We distribute each of them to different remote experimenters. Each one of them chooses, independently and randomly, whether to measure color or shape and records the result. The experiment is repeated many times, but always with three quantons in the GHZ state.

Each individual experimenter gets random results. Measuring the shape of a quanton, it is equally likely to get a square or a circle; by measuring the color of a quanton, he is equally likely to get red or blue. While everything is ordinary.

But when experimenters get together and compare the results, the analysis shows an amazing result. Suppose we call a square shape and red color “good”, and circles and blue color - “evil”. Experimenters discover that if two of them decide to measure the shape and the third chooses color, then either 0 or 2 measurement results are “evil” (i.e., round or blue). But if all three decide to measure color, then either 1 or 3 measurements are evil. This is predicted by quantum mechanics, and this is exactly what is happening.

Question: Is the amount of evil even or odd? In different dimensions both possibilities are realized. We have to abandon this issue. It does not make sense to talk about the amount of evil in the system without regard to how it is measured. And this leads to contradictions.

The effect of GHZ, as described by physicist Sydney Coleman, is "a slap in the face of quantum mechanics." It destroys the usual, experience-based expectation that physical systems have predetermined properties that are independent of their measurement. If this were so, then the balance of good and evil would not depend on the choice of types of measurements. After you accept the existence of the GHZ effect, you will not forget it, and your horizons will be expanded.

So far, we are discussing how entanglement does not allow us to assign unique independent states to several quantons. The same reasoning applies to changes in a single quanton over time.

We are talking about “tangled stories” when it is impossible for a system to assign a specific state at any given time. Just as in traditional entanglement, we exclude some possibilities, we can create intricate stories by taking measurements that collect partial information about past events. In the simplest tangled stories, we have one quanton that we studied at two different points in time. We can imagine a situation where we determine that the shape of our quanton was both square or round both times, but both situations remain possible. This is a temporal quantum analogy to the simplest variants of entanglement described earlier.

Using a more complex protocol, we can add a bit of additionality to this system, and describe the situations that cause the "many-world" property of quantum theory. Our quanton can be prepared in the red state, and then measured and obtained blue. And as in the previous examples, we cannot permanently assign a color property to a quanton in the interval between two dimensions; he has no definite form. Such stories realize, in a limited, but completely controlled and accurate way, the intuition inherent in the picture of the multiplicity of worlds in quantum mechanics. A certain state can be divided into two conflicting historical trajectories, which are then reunited.

Erwin Schrödinger, the founder of quantum theory, who was skeptical about its correctness, emphasized that the evolution of quantum systems naturally leads to states whose measurement can give extremely different results. His thought experiment with the "Schrödinger cat" postulates, as we know, quantum uncertainty, derived from the level of influence on the mortality of the feline. It is impossible to assign the property of life (or death) to a cat before measurement. Both, or neither of them, exist together in the other world of possibilities.

Everyday language is poorly adapted to explain quantum complementarity, in particular, because everyday experience does not include it. Practical cats interact with the surrounding air molecules, and other objects, in completely different ways, depending on whether they are alive or dead, so in practice the measurement passes automatically, and the cat continues to live (or not to live). But stories with intricacies describe the quantons that are Schrödinger's kittens. Their full description requires that we take into consideration two mutually exclusive trajectories of properties.

Controlled experimental realization of confusing stories is a delicate thing, because it requires the collection of partial information about quantons. Conventional quantum measurements usually collect all the information at once — for example, determine the exact shape or exact color — instead of obtaining partial information several times. But this can be done, albeit with extreme technical difficulties. In this way, we can assign a certain mathematical and experimental meaning to the spread of the concept of “multiplicity of worlds” in quantum theory, and demonstrate its reality.

The concept of quantum entanglement is shrouded in a charming aura of mystery, as well as the (somehow) related requirement of quantum theory about the need for "many worlds." And, nevertheless, in its essence these are scientific ideas with a mundane meaning and concrete applications. I would like to explain the concepts of entanglement and multitude of worlds as simply and clearly as I know them myself.

')

I

Entanglement is considered a phenomenon unique to quantum mechanics - but it is not. In fact, for a start it will be clearer (although this is an unusual approach) to consider a simple, non-quantum (classical) version of entanglement. This will allow us to separate the subtleties associated with the intricacies themselves from other oddities of quantum theory.

Confusion appears in situations in which we have partial information about the state of the two systems. For example, two objects can become our systems — let's call them kaons. “K” will denote “classic” objects. But if you really want to imagine something specific and pleasant - imagine that these are cakes.

Our kaons will have two shapes, square or round, and these shapes will denote their possible states. Then the four possible joint states of the two kaons will be: (square, square), (square, circle), (circle, square), (circle, circle). The table shows the probability of the system being in one of the four listed states.

We will say that kaons are “independent” if knowledge of the state of one of them does not give us information about the state of the other. And this table has this property. If the first kaon (cake) is square, we still do not know the shape of the second. Conversely, the form of the second does not tell us anything about the form of the first.

On the other hand, we will say that two kaons are confused if the information about one of them improves our knowledge about the other. The second sign will show us a strong confusion. In this case, if the first kaon is round, we will know that the second one is also round. And if the first kaon is square, then the second one will be the same. Knowing the form of one, we uniquely determine the form of the other.

The quantum version of entanglement looks, in fact, also - this is a lack of independence. In quantum theory, states are described by mathematical objects called the wave function. The rules that combine wave functions with physical capabilities, create very interesting difficulties, which we will discuss later, but the basic concept of intricate knowledge, which we demonstrated for the classical case, remains the same.

Although cakes cannot be considered quantum systems, the entanglement of quantum systems arises naturally — for example, after a collision of particles. In practice, uncontaminated (independent) states can be considered rare exceptions, since the interaction of systems between them leads to correlations.

Consider, for example, molecules. They consist of subsystems - specifically, electrons and nuclei. The minimum energy state of the molecule, in which it is usually located, is a very entangled state of electrons and the nucleus, since the arrangement of these constituent particles will not be independent. When the nucleus moves, the electron moves with it.

Let's return to our example. If we write Φ ■, Φ ● as wave functions describing system 1 in its square or circular states and ψ ■, ψ ● for wave functions describing system 2 in its square or circular states, then in our working example all states can be described , as:

Independent: Φ ■ ■ + Φ ■ ψ ● + Φ ● ■ + Φ ● ●

Entangled: Φ ■ ■ + Φ ● ψ ●

The independent version can also be written as:

(Φ ■ + Φ ●) (ψ ■ + ψ ●)

Note that in the latter case, the brackets clearly divide the first and second systems into independent parts.

There are many ways to create entangled states. One of them is to measure the composite system that gives you partial information. You can find out, for example, that the two systems agreed to be of the same form, without knowing at the same time which form they chose. This concept will become important later.

More characteristic effects of quantum entanglement, such as the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) and Greenberg-Horn-Seilinger (GHZ) effects, arise from its interaction with another property of quantum theory called the complementarity principle. To discuss EPR and GHZ, let me first introduce this principle to you.

Up to this point, we imagined that kaons come in two forms (square and round). Now imagine that there are two more colors - red and blue. Considering classical systems, for example, cakes, this additional property would mean that a kaon can exist in one of four possible states: a red square, a red circle, a blue square and a blue circle.

But quantum cakes are quantum-like ... Or quantons ... They behave quite differently. The fact that a quanton in some situations may have a different shape and color does not necessarily mean that it simultaneously possesses both form and color. In fact, the common sense that Einstein demanded from physical reality does not match the experimental facts that we will soon see.

We can measure the shape of the quanton, but at the same time we will lose all the information about its color. Or we can measure color, but lose information about its shape. According to quantum theory, we cannot measure both shape and color at the same time. No one’s view of quantum reality is complete; we have to take into account many different and mutually exclusive pictures, each of which has its own incomplete picture of what is happening. This is the essence of the complementarity principle, such as Niels Bohr put it.

As a result, quantum theory forces us to be cautious in attributing to the properties of physical reality. In order to avoid contradictions, we have to admit that:

There is no property if it is not measured.

Measurement is an active process that changes the system being measured.

II

We now describe two exemplary, but not classical, illustrations of the oddities of quantum theory. Both were tested in rigorous experiments (in real experiments, people measure not the shapes and colors of cakes, but the angular moments of electrons).

Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen (EPR) described a surprising effect when the two quantum systems are entangled. The EPR effect combines a special, experimentally attainable form of quantum entanglement with the principle of complementarity.

An EPR pair consists of two quantons, each of which can measure shape or color (but not both at once). Suppose we have many such pairs, they are all the same, and we can choose which measurements we make over their components. If we measure the shape of one of the members of an EPR pair, we are equally likely to get a square or a circle. If we measure the color, then with equal probability we get red or blue.

Interesting effects, which seemed to be paradoxical to EPR, arise when we measure both members of a pair. When we measure the color of both members, or their shape, we find that the results always coincide. That is, if we find that one of them is red and then measure the color of the second, we also find that it is red — and so on. On the other hand, if we measure the shape of one and the color of another, no correlation is observed. That is, if the first was a square, then the second with the same probability can be blue or red.

According to quantum theory, we will get such results, even if the two systems will share a huge distance and measurements will be carried out almost simultaneously. The choice of the type of measurements in one place, apparently, affects the state of the system in another place. This “frightening long-range”, as Einstein called it, apparently requires the transfer of information - in our case, information about the measurement - with a speed exceeding the speed of light.

But is it? Until I know what result you got, I do not know what to expect me. I get useful information when I know your result, not when you take a measurement. And any message containing the result you received must be transmitted in any physical way, slower than the speed of light.

Upon further study, the paradox breaks down even more. Let's consider the state of the second system, if the measurement of the first gave a red color. If we decide to measure the color of the second quanton, we get red. But by the principle of complementarity, if we decide to measure its shape when it is in the “red” state, we will have equal chances of getting a square or a circle. Therefore, the EPR result is logically predefined. This is simply a retelling of the principle of complementarity.

There is no paradox in the fact that remote events correlate. After all, if we put one of the two gloves from the pair into the boxes and send them to different ends of the planet, it is not surprising that by looking in one box, I can determine which hand the other glove is intended for. Similarly, in all cases, the correlation of EPR pairs must be fixed to them when they are near and therefore they can withstand the subsequent separation, as if having a memory. The strangeness of the EPR paradox is not in itself the possibility of correlation, but in the possibility of its preservation in the form of add-ons.

III

Daniel Greenberger, Michael Horn and Anton Zeilinger opened another excellent example of quantum entanglement. It includes our three quantons, which are in a specially prepared entangled state (GHZ-state). We distribute each of them to different remote experimenters. Each one of them chooses, independently and randomly, whether to measure color or shape and records the result. The experiment is repeated many times, but always with three quantons in the GHZ state.

Each individual experimenter gets random results. Measuring the shape of a quanton, it is equally likely to get a square or a circle; by measuring the color of a quanton, he is equally likely to get red or blue. While everything is ordinary.

But when experimenters get together and compare the results, the analysis shows an amazing result. Suppose we call a square shape and red color “good”, and circles and blue color - “evil”. Experimenters discover that if two of them decide to measure the shape and the third chooses color, then either 0 or 2 measurement results are “evil” (i.e., round or blue). But if all three decide to measure color, then either 1 or 3 measurements are evil. This is predicted by quantum mechanics, and this is exactly what is happening.

Question: Is the amount of evil even or odd? In different dimensions both possibilities are realized. We have to abandon this issue. It does not make sense to talk about the amount of evil in the system without regard to how it is measured. And this leads to contradictions.

The effect of GHZ, as described by physicist Sydney Coleman, is "a slap in the face of quantum mechanics." It destroys the usual, experience-based expectation that physical systems have predetermined properties that are independent of their measurement. If this were so, then the balance of good and evil would not depend on the choice of types of measurements. After you accept the existence of the GHZ effect, you will not forget it, and your horizons will be expanded.

IV

So far, we are discussing how entanglement does not allow us to assign unique independent states to several quantons. The same reasoning applies to changes in a single quanton over time.

We are talking about “tangled stories” when it is impossible for a system to assign a specific state at any given time. Just as in traditional entanglement, we exclude some possibilities, we can create intricate stories by taking measurements that collect partial information about past events. In the simplest tangled stories, we have one quanton that we studied at two different points in time. We can imagine a situation where we determine that the shape of our quanton was both square or round both times, but both situations remain possible. This is a temporal quantum analogy to the simplest variants of entanglement described earlier.

Using a more complex protocol, we can add a bit of additionality to this system, and describe the situations that cause the "many-world" property of quantum theory. Our quanton can be prepared in the red state, and then measured and obtained blue. And as in the previous examples, we cannot permanently assign a color property to a quanton in the interval between two dimensions; he has no definite form. Such stories realize, in a limited, but completely controlled and accurate way, the intuition inherent in the picture of the multiplicity of worlds in quantum mechanics. A certain state can be divided into two conflicting historical trajectories, which are then reunited.

Erwin Schrödinger, the founder of quantum theory, who was skeptical about its correctness, emphasized that the evolution of quantum systems naturally leads to states whose measurement can give extremely different results. His thought experiment with the "Schrödinger cat" postulates, as we know, quantum uncertainty, derived from the level of influence on the mortality of the feline. It is impossible to assign the property of life (or death) to a cat before measurement. Both, or neither of them, exist together in the other world of possibilities.

Everyday language is poorly adapted to explain quantum complementarity, in particular, because everyday experience does not include it. Practical cats interact with the surrounding air molecules, and other objects, in completely different ways, depending on whether they are alive or dead, so in practice the measurement passes automatically, and the cat continues to live (or not to live). But stories with intricacies describe the quantons that are Schrödinger's kittens. Their full description requires that we take into consideration two mutually exclusive trajectories of properties.

Controlled experimental realization of confusing stories is a delicate thing, because it requires the collection of partial information about quantons. Conventional quantum measurements usually collect all the information at once — for example, determine the exact shape or exact color — instead of obtaining partial information several times. But this can be done, albeit with extreme technical difficulties. In this way, we can assign a certain mathematical and experimental meaning to the spread of the concept of “multiplicity of worlds” in quantum theory, and demonstrate its reality.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/372539/

All Articles