Why interrupted sleep is a great time for creative work.

People used to wake up in the middle of the night to think, make notes, or make love. What did we lose by falling asleep all night?

4:18 AM Firewood burned in the hearth and only orange pieces remained, which would soon turn into ashes. Orion hunter climbed over the hill. The shimmering "V" of Taurus stands directly overhead, and points to the Seven Sisters. Sirius, one of the dogs of Orion, twinkles red, blue, purple - like a galactic disco ball. The night goes on, and the old dog will soon sit behind the hill.

4:18 AM, and I do not sleep. Such an early awakening is usually considered a disorder, a failure in the natural rhythm of the body is a sign of depression or arousal. Indeed, after waking up at 4 am, in my head was buzzing. And although I am a positive person, but when I lie in the dark, anxiety appears in my thoughts. It seems to me that it is better to get up than to lie in bed, balancing on the verge of sleepwalking.

')

If I write in this watch, black thoughts become clear and colorful. They are formed into words and sentences, one clinging to another - like a string of elephants holding their trunks by their tails. At this time of night, my brain works differently: I can write, but not edit. I can add, but not take away. For clarity, daytime consciousness is necessary. I work a few hours and then fall asleep again.

All people, animals, insects, and birds have built-in clocks, biological devices driven by genes, proteins, and molecular cascades. This internal clock depends on an infinite but variable cycle of light and darkness, which is due to the rotation and tilt of our planet. They control basic physiological, neurological and behavioral systems in accordance with an approximately 24-hour cycle, known as circadian rhythm. It affects our mood, desires, appetite, patterns of sleep, and a sense of time.

The Romans, the Greeks, the Incas woke up without an iPhone alarm clock or digital radio clock. Their time was managed by nature: sunrise, evening chorus, needs of field crops or livestock. Until the 14th century, the passage of time was marked by sundials and hourglasses, and then the first mechanical clocks appeared on monasteries and churches. By 1800, the mechanical watch was already worn around the neck, wrists and lapels. You could make appointments, time for eating and going to bed.

Societies built on industrialization and accurate time spawned the notion of urgency and concepts such as “on time” or “loss of time”. Clocks began to diverge more and more with natural time, but light and darkness still controlled working hours and social structures. But everything changed in the 19th century.

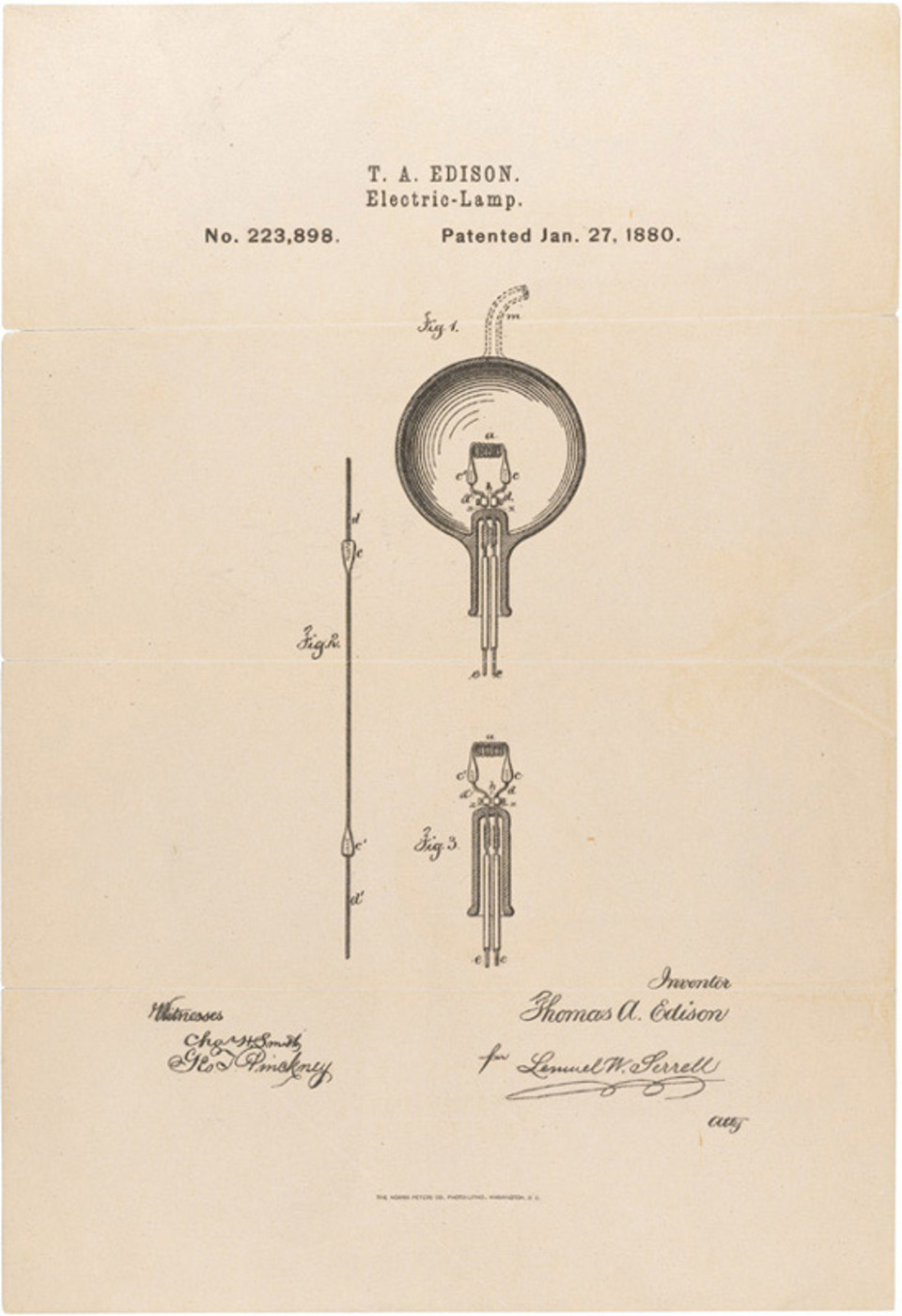

Edison's patent for a light bulb, 1879

The light came on.

Modern electric lighting has revolutionized nightlife and sleep. According to historian Roger Ekirch, the author of the book “At Sunset's Day: Night in Past Times” (At Day's Close: Night in Times Past (2005)), before Edison the dream was divided into two different parts, separated by a period of wakefulness that lasted from one to several hours. This mode was called split sleep [segmented sleep].

Sleep patterns of the past may surprise us today. It can be decided that circadian rhythms should raise us at sunrise, but many animals and insects do not sleep in one continuous piece, but little by little, several hours at a time, or in two separate steps. Ecirch believes that if people are left to sleep in a natural way, they will not sleep in one continuous segment either.

He bases his point of view on 16 years of research, during which he studied hundreds of historical documents, from antiquity to modern times. They included diaries, court records, books on medicine and fiction. He found countless references to the "first" and "second" sleep in the English language. Other languages also describe this sleep pattern, for example, premier sommeil in French, primo sonno in Italian, primo somno in Latin. The way the divided dream was routinely described led Ekirkh to the conclusion that such a regime was once a familiar and daily part of sleep and wakefulness.

Before the invention of electric lighting, night was associated with crime and fear - people did not leave the house and went to bed early. The time of the first sleep varied depending on the season and social class, but usually began a couple of hours after sunset and lasted three to four hours, and then, in the middle of the night, people naturally woke up. Before the electric bulbs in rich houses, other sources of artificial matchmaker were used — gas lamps, for example — that is why they went to bed there later. Interestingly, Echirch found fewer references to a separate dream associated with rich houses.

People who slept in a separate sleep, night wakefulness was used for reading, prayers and writing letters, parsing dreams, talking and making love. Ackirh points out that after a hard day’s work, people were too tired for the pleasures of love before the first night (busy people of today also appreciate it), but upon awakening at night, our ancestors were rested and ready for fun. After nightly activities, people again became sleepy, and fell asleep with a second sleep (also for 3-4 hours), before meeting a new day. We can imagine how we go to bed at 9 pm in the winter, wake up at midnight, read and talk until 2 am, and then we sleep again until 6.

Ackirch found that references to double sleep almost disappeared in the early 20th century. Electricity increased the amount of light, and daytime activities spread to night time. Illuminated streets have become safer, and it has become fashionable to use evenings for social activities. The sleep-back moved further, and the nighttime wake, incompatible with the increased day, disappeared. Ackirch argues that with the loss of night wakefulness, we have lost its benefits.

He told me that nighttime wakefulness is different from daytime, at least according to the documents he found. The third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, read books on moral philosophy at bedtime to “reflect on” them between two periods of sleep. The 17th century English poet Francis Quarles called darkness and silence help in contemplating inner reflection:

Let’s end your body's first sleep state: then your body’s best temper, then you’re the least incumbrance; then no noise shall disturbe thine ear; no object shall divert thine eye. [let the end of the first sleep from rest raise you; Yes, the body will receive the best mood, and the soul - the least interference, but not interfere with the noise of the ear, and will not distract any object of the eyes]

My own night waking experience confirms the difference between day and night awakenings. The work of the night brain is more like a dream. In a dream, consciousness creates pictures from memories, hopes and fears. In the night, a sleepy brain can evoke new ideas based on dreams and apply them to creative activities. In the essay “The Lost Dream” (2001), Echirch wrote that many people, waking up after their first sleep, had to be in a sleepy state, “which, thus, contributed to the assimilation of visions before a person once again became unconscious. In the absence of sounds, illness and other discomfort, his condition was likely to be relaxed and his concentration complete. ”

The ideas of Ekirch about divided sleep are supported not only by old documents and archives - they find the facts in their support in modern research. Psychiatrist Thomas Wehr from the US State Institute of Mental Health found that a divided dream returns when the artificial light is canceled. During the one-month experiment in the 1990s, subjects had faith in access to light for 10 hours a day, not for 16 hours, as is usually the case now. And during this more natural cycle, Ver noted that "the duration of sleep increased, and usually divided into two symmetrical times, lasting several hours, with an interval of wakefulness from 1 to 3 hours between them."

The works of Ekirch and Vera are used in sleep studies. The ideas of Ekirch were discussed at the annual conference of the North American professional sleep sleep study communities 2013. One of the biggest consequences of the work is the fact that the most common variant of insomnia, “mid-night insomnia,” is not a deviation, but an attempt to return to the natural form of sleep. This shift in perception has greatly reduced my worries about waking at night.

It's 7:04 in the morning. I wrote for almost three hours, and now I go back to bed, to the second dream. Later in the afternoon I will work again. I can afford a divided dream because of the lifestyle that I have provided myself (no children, I work for myself).

But I also had to adapt my sleep methods to the working schedule from nine to five, which is quite difficult to do. Few sounds scare more than the buzz of an alarm clock, when you spent several hours waking and just fell asleep. The struggle of the “natural” sleep mode with a rigid social structure — hours, industrialization, schoolwork, working time — results in a shared dream that looks like a deviation, and not like a boon.

Creative people find ways to live outside “from nine to five,” either because of the success of their books, drawings, and music, so they don’t need regular work, or because they specifically look for work with flexible schedules, for example freelance.

In Daily Rituals: How Artists Work (Daily Rituals: How Artists Work (2013)), Mason Currey describes the habits of famous writers and artists, many of whom rose early, and a few used shared sleep. Curry discovered that some stumbled upon a divided sleep regime by accident. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, for example, woke up at 4 am and could not sleep - so he worked for 3-4 hours, and then fell asleep again. Nobel laureate, writer Knut Hamsun [Knut Hamsun] often woke up after sleeping for a couple of hours, so he kept a pencil and paper next to the bed, and, according to him, “started writing right away in the dark if he felt the flow through me”. Psychologist B.F. Skinner kept a tablet, paper and a pencil next to the bed to work during periods of nighttime wake, and author Marilynne Robinson often woke up and read or wrote during what she called this watch, “supportive insomnia.”

Some of us love the morning, others love the evening; larks and owls. Curry says that creative people working at night “use the optimal state of consciousness for their work,” governed by the natural rhythms of the person, not by choice.

Writer Nicholson Baker [Nicholson Baker] was the only friend Curry, consciously practicing a separate sleep. Curry told me that Baker knows about his writing habits, and he likes to experiment with new writing rituals for each new book. Therefore, it seemed appropriate to set aside a couple of fruitful hours for work, creating two mornings in one day.

And when Baker wrote his “Box of Matches” (A Box of Matches (2003)), a story about a writer who woke up at 4 am, lit a fire and wrote while the whole family was sleeping, he also practiced this ritual, and then returned to bed second sleep.

“I found that by lighting and supporting this early light, I began to concentrate better,” Baker told The Paris Review in an interview. - There is something simple and meditatively pleasant in making fire at four in the morning. I began to write unrelated sentences, and writing was easy. ”

It is this sleepy stream that describes the creative work carried out in the middle of the night. Between dreams there is peace, the absence of distracting moments and a stronger connection with dreams.

Also at night hormonal changes occur in the brain, suitable for creativity. Ver noted that during the night of wakefulness, the pituitary gland secretes a lot of prolactin. This hormone is associated with sensations of rest and sleepy visions that we experience, going to sleep, or upon waking up. It stands out when we feel sexual satisfaction, when a nursing mother produces milk, and because of it the hen hatch eggs for a long time. It changes the state of mind.

Prolactin levels increase in sleep, but Ver discovered that (along with melatonin and cortisol), it stands out during “quiet wakefulness” between dreams under the influence of a natural change of day and night, and is not associated with sleep as such. Blissfully intoxicated with prolactin, our nocturnal brains allow ideas to appear and interlace as if in a dream.

Ver believes that the modern schedule not only changed our sleep patterns, but also stole the ancient connection between dreams and awakening from us, and “can explain at a physiological level why modern people have lost touch with an inexhaustible source of myths and fantasies.”

Ackirh agrees: “Having transformed night into day, modern technology blocked the road to the human soul, and using the words of the 17th century English poet Thomas Middleton,“ destroyed our first dream and tricked our dreams and fantasies ”.

Modern technology may pollute the channels connecting us with our dreams, encourages people to become out of sync and the natural mode, but it can also lead us back. The industrial revolution has flooded us with light, and the digital may be more supportive of a person using shared sleep.

The technology encourages the invention of new ways of organizing time. Home-based work, freelancing and free scheduling are becoming increasingly popular, as are the concepts of digital nomads, online and remote workers. All of them can use more flexible modes, allowing people who are awake at night to find a balance between divided sleep and work. If we can set aside time to wake up at night and reflect with the help of our brains filled with prolactin, we may be able to regain our creative potential and fantasies enjoyed by our ancestors. According to Ekirch, “they slept through the first sleep, to think of a kaleidoscope of partially crystallized visions, slightly blurred, but generally bright enough pictures, generated by their dreams.”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/372461/

All Articles