World without work

For hundreds of years, experts predicted that machines would make workers unnecessary. And this moment comes. Is it good or bad?

1. Youngstown, USA [a city in the northeastern United States, in Ohio]

The disappearance of work is still a futuristic concept for the majority of US residents, but for the city of Youngstown this concept has already become history, and its people can call the turning point with certainty: September 19, 1977.

For most of the 20th century, the city’s steel mills flourished to such an extent that the city was a model of the American dream, boasting a record median income, and the percentage of houses owned was one of the highest in the country. But after moving production overseas after World War II, the city began to lose ground, and on a gray September day in 1977, Youngstown Sheet and Tube announced the closure of the Campbell Works steel mill. In five years, the number of jobs in the city has decreased by 50,000, while industrial wages have fallen by $ 1.3 billion. This had such a tangible effect that even a special term was born to describe it: regional depression.

')

Youngstown has changed, not only because of a disruption in the economy, but also because of cultural and psychological decline. The number of depressions, family problems and suicides has increased dramatically. The loading of the regional center of psychological health has tripled in ten years. Four prisons were built in the city in the 1990s - a rare example of growth in this area. One of the few projects of suburban construction has become a museum dedicated to the decline in steel production.

This winter, I traveled to Ohio to understand what could happen if technology replaces most of human labor. I did not need a tour of the automated future. I drove because Youngstown became a national metaphor for the disappearance of work, a place where the middle class of the 20th century became a museum piece.

“The history of Youngstown is the history of America, because it shows that when work disappears, the cultural unity of the area is destroyed,” said John Rousseau, a professor of labor studies at Youngstown State University. “The decline of culture means more than the decline of the economy.”

Over the past few years, the United States has partially gotten out of unemployment created by the Great Recession, but some economists and technologists still warn that the economy is at a critical point. Understanding the data on the labor market, they see bad signs temporarily disguised by a cyclical economic recovery. Raising their heads from spreadsheets, they see automation at all levels - robots work in the operating rooms and at the cash registers of fast foods. They see in their imagination robotic vehicles, darting through the streets, and UAV drones rising in the sky, replacing millions of drivers, warehouse workers and salespeople. They see that the capabilities of machines, already quite impressive, are increasing exponentially, while the human capabilities remain at the same level. They ask themselves: are there any posts that are out of danger?

Futurists and fantasy writers have long and with frivolous joy waiting for robots to take jobs. They represent how hard monotonous work gives way to doing nothing and endless personal freedom. Rest assured: if the capabilities of computers continue to increase, and their cost decreases, a huge amount of life and luxury items will become cheaper, and this will mean an increase in wealth. At least in terms of national scale.

Let us leave aside the questions of redistributing this wealth - the widespread disappearance of work will lead to unprecedented social changes. If John Rousseau is right, then saving work is more important than saving specific jobs. Diligence was for America an unofficial religion since its inception. The sacredness and primacy of the work underlie the country's politics, economics and social interactions. What can happen if the work disappears?

The labor force in the USA is shaped by thousands of years of technical progress. Agricultural technology led to the birth of farming, the industrial revolution transferred people to factories, and globalization and automation brought them back, giving rise to a nation of services. But in all these shakes the number of jobs increased. Now something completely different is hanging over us: the era of technological idleness, in which computer scientists and programmers deprive us of work, and the total number of jobs is reduced constantly and permanently.

This fear is not new. The hope that machines will free us from hard work has always intertwined with the fear that they will take away our livelihood. During the Great Depression, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that technical progress would provide us with a 15-hour work week and plenty of rest by 2030. At about the same time, President Herbert Hoover received a letter containing a warning about technology as a "Frankenstein monster" who threatened production and threatened to "devour civilization." (It's funny that the letter came from the mayor of Palo Alto). In 1962, John F. Kennedy said: "If people have a talent for creating new machines that deprive people of work, they will have the talent to give these people work again." But two years later, a commission of scientists and social activists sent an open letter to President Johnson, claiming that the "cybernation revolution" would create a "separate nation of poor, inept unemployed," who could neither find a job nor afford first-rate items.

In those days, the labor market has denied the fears of petrels, and according to the latest statistics, disproves them in our time. Unemployment is barely more than 5%, and in 2014 there was the best growth in the number of jobs in this century. One can understand the opinion that recent predictions about the disappearance of jobs simply formed the newest chapter in a long story called “Boys who shouted 'robots!'”. In this story, the robot, unlike the wolf, never appeared.

The absence of work is often rejected under the pretext of “Luddit delusions”. In the 19th century in Britain, foolish people smashed weaving machines at the dawn of the industrial revolution, in the fear that they would lose their weavers. But one of the most sober-minded economists is beginning to fear that they were not so wrong - they just hurried slightly. When the former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers studied at MIT in the 1970s, many economists disdainfully viewed “fools who thought automation would lead to the disappearance of jobs,” as he put it at the summer meetings of the State Economic Research Committee in July 2013. “And until recently, I did not consider this question difficult: the Luddites were wrong, and those who believe in technology and progress are right. Now I’m not so sure about that. ”

2. Why is it worth shouting "robots"

And what does “end of work” mean? It does not mean the inevitability of full unemployment, or even 30-50% of unemployment in the United States in the next 10 years. The technology will simply continually and smoothly put pressure on the value of work and the number of jobs. Wages and the proportion of full-time people working in their prime will be reduced. Gradually, this may lead to a new situation in which the idea of work as the main type of activity of an adult person will disappear for a large part of the population.

After 300 years of screaming “wolves!”, Three arguments emerged in favor of a serious attitude to the approaching misfortune: the superiority of capital over labor, the silent death of the working class, and the amazing flexibility of information technology.

- Loss of work . The first thing that can be seen in the period of technological crowding out is a reduction in the amount of human labor, contributing to economic growth. Signs of this process are visible for a long time. The share of wages in the total cost of production decreased gradually in the 1980s, then rose slightly in the 90s, and then continued to decrease after 2000, accelerating from the beginning of the Great Recession. Now it is at the lowest level in the entire history of observations since the mid-20th century.

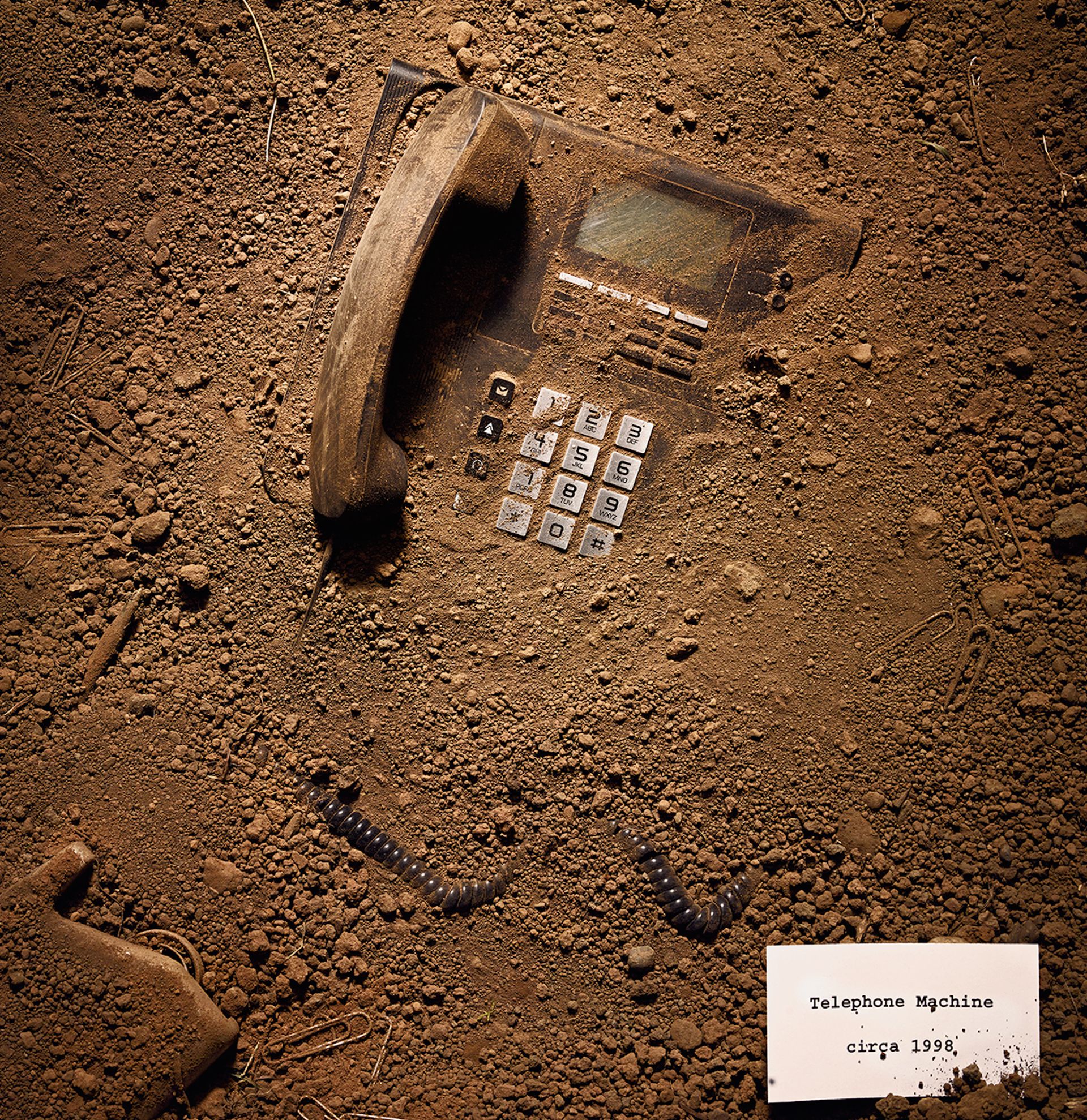

This theory is explained by various theories, including globalization, and the consequent loss of the opportunity to bargain for the level of wages. But Lucas Karabarbounis [Loukas Karabarbounis] and Brent Neiman [Brent Neiman], economists at the University of Chicago, estimated that almost half of this decrease was due to the replacement of working people with computers and programs. In 1964, the largest US-owned company, AT & T, was worth $ 267 billion for current money, and it employed 758,611 people. Today, telecom giant Google is worth $ 370 billion, but it employs 55,000 people - less than a tenth of AT & T.

- The number of unorganized adults and young people . The proportion of middle-aged working Americans, from 25 to 54 years, has been falling since 2000. Among men, the decline began even earlier - the proportion of non-working men has doubled since the 1970s, while the increase during the recovery was the same as the increase during the Great Recession. In general, every sixth man of middle age either looks for a job, or does not work at all. This statistician economist Tyler Cowen calls the "key" to understand how the American workforce is deteriorating. Common sense dictates that under normal conditions, almost all men in this age group who are at the peak of opportunities and are much less likely than women who care for children should work. But less and less work.

Economists are not sure why they stop doing this - one of the explanations speaks of technological changes that led to the disappearance of the works to which these men were adapted. Since 2000, the number of manufacturing jobs has fallen by 5 million, or 30%.

Young people entering the labor market also face difficulties - and for many years now. In the six years of recovery, the proportion of recent graduates working in unskilled jobs that do not require education is still higher than in 2007 - or even in 2000. And the composition of these unskilled jobs migrates from well-paid, like electricians, to low-paid ones, like a waiter. Most people want to get an education, but graduates' salaries have fallen by 7.7% since 2000. In general, the labor market has to prepare for less wages. The distorting effect of the Great Recession makes us more cautious about the overuse of interpreting these indicators, but most of them began even before it, and they do not bode well for the future of work.

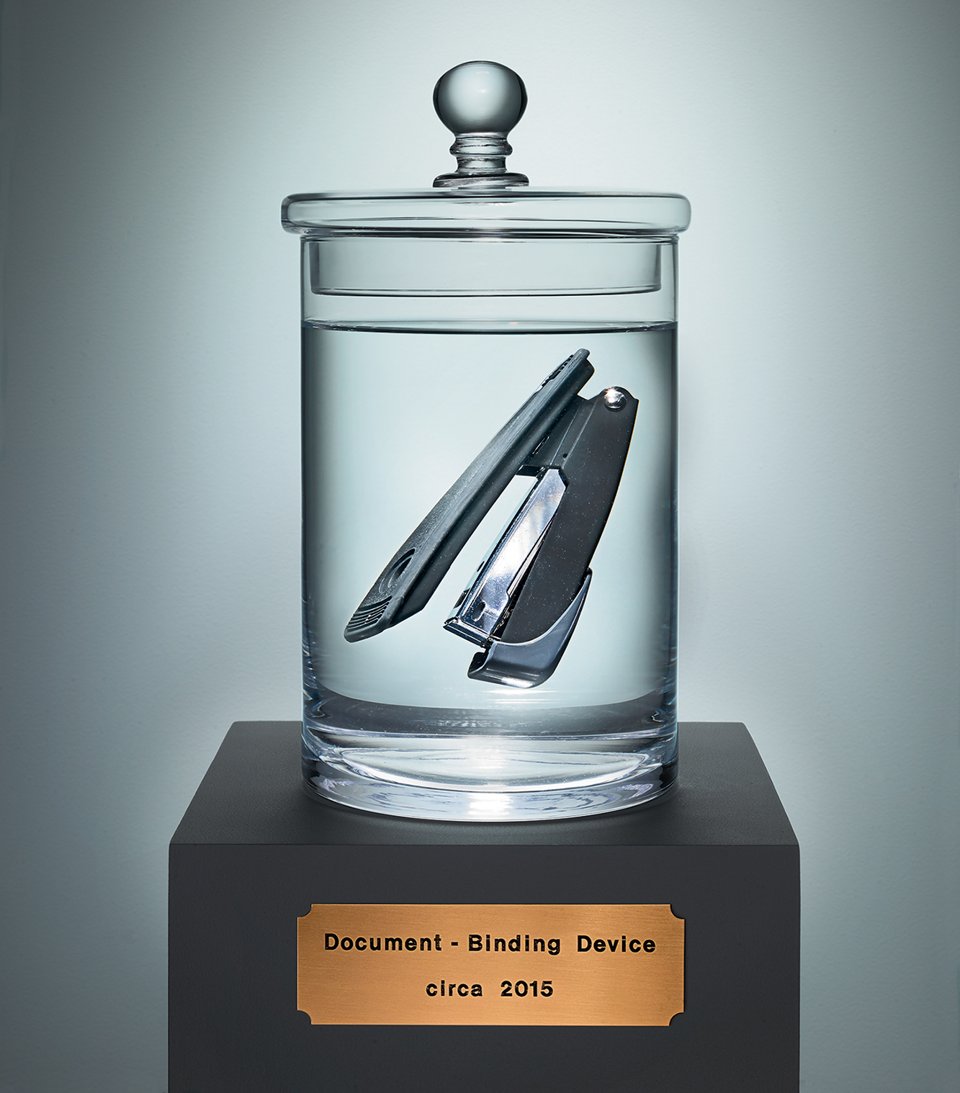

- Long-term effects from the introduction of software . One argument against the fact that the technology will replace a huge number of workers, is that all new gadgets like self-service kiosks in pharmacies have not replaced their fellow people. But it takes years for employers to get used to replacing people with machines. The robotics revolution in manufacturing began in 1960–70, but the number of workers there grew until the 1980s and then fell during subsequent recessions. Similarly, “personal computers already existed in the 1980s,” says Henry Siu, an economist at the University of British Columbia, “but their influence on offices and administrative work was not noticeable until the 1990s, and then suddenly, during last recession, it became huge. So today you have self-service kiosks, and the promise of cars without a driver, flying drones and storekeepers robots. These tasks machines can perform instead of people. But we can see the effect only during the next recession, or the one that will come after it. ”

Some observers say that humanity is a ditch that cannot be overcome by machines. They believe that the ability of a person to sympathize, understand and create, cannot be imitated. But, according to Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAffie in their book “The Second Age of Machines,” computers are so flexible that it is impossible to predict their use in 10 years. Who would have guessed in 2005, two years before the release of the iPhone, that smartphones would threaten the jobs of hotel employees in ten years, since the owners of the premises will be able to rent their houses and apartments to strangers via Airbnb? Or that the company behind the popular search engine will work on a robotic car that threatens drivers - the most popular work of Americans?

In 2013, researchers at Oxford University predicted that in the next 20 years, up to half of all work in the United States would be available. It was a bold prediction, but in some cases it was not so crazy. For example, the work of psychologists was called little computerized. But some studies say that people are more honest in cases where they are undergoing therapy with computers, because the machine does not condemn them. Google and WebMD can already answer some questions that you want to ask the psychologist. This does not mean that psychologists will disappear after weavers. This shows how computers easily penetrate into areas that were previously viewed as belonging only to humans.

After 300 years of amazing innovation, people did not come to a total lack of work and were not replaced by machines. But in describing how the situation may change, some economists point to a broken career as the second most important species in US economic history: horses.

For centuries, people have come up with technologies that increase the productivity of horses - plows for farming, swords for battles. One would imagine how the development of technology would make this animal even more necessary for farmers and warriors - perhaps the two most important professions in history. Instead, inventions appeared that made horses unnecessary — a tractor, a car, a tank. After the tractor came out on farms in the early 20th century, the population of horses and mules began to slowly decline, falling by 50% by 1930, and by 90% by 1950.

People can do much more than trot, carry a load and pull a strap. But the skills needed in most offices are unlikely to use the full power of our intellect. Most jobs are boring, repetitive, and easy to learn. Among the most popular posts in the USA are a salesman, cashier, waiter and office clerk. Together, they make up 15.4 million people — almost 10% of the total workforce, or more than the total people working in Texas and Massachusetts. And all these posts are easily automated, according to a research by Oxford scientists.

Technology also creates new jobs, but the creative side of creative destruction is easy to exaggerate. Nine out of ten workers today are busy with work that existed 100 years ago, and only 5% of jobs created from 1993 to 2013 in high-tech sectors such as computer technology, programming and telecommunications. The newest industries are at the same time the most effective from the point of view of labor - they simply do not need a large number of people. That is why economist Robert Skidelsky, comparing the exponential growth of computer power with the increasing complexity of work, said: "Sooner or later, jobs will end."

Is it, and is it inevitable? Not. While signs of this vague and indirect. The deepest and most complicated labor market restructuring happens during recessions: we will know more after a couple of next turns. But the opportunity remains serious enough, and the consequences of this are destructive enough so that we begin to think about how society can look, without universal work, to push it towards better outcomes and save it from the worst.

Paraphrasing William Gibson's science fiction, in the present some fragments of the future are unevenly distributed, in which they got rid of work. I see three overlapping possibilities for reducing the likelihood of finding a job. Some people forced out of the formal labor force will devote their lives to freedom or leisure; some will build productive communities outside the workplace; some will fight fiercely and meaninglessly to regain their efficiency, creating jobs in the informal economy. These are options for the future - consumption, community creativity and odd jobs. In any combination, it is clear that the country will have to accept a fundamentally new role of government.

3. Consumption: the paradox of leisure

The work consists of three things, according to Peter Freise, the author of the forthcoming book “Four Future”, on how automation will change America: the way goods are produced [and services are translated], the method of making money, and activities that make sense into the existence of people. “Usually we combine these things,” he says to me, “because today people have to pay so that, so to speak, you have a light. But in the abundant future you will not need to do this, and we need to think of ways to live easier and better without work. ”

Fraz belongs to a small group of writers, scientists, and economists — they are called "researchers of the post-labor future," who welcome the end of labor. American society has “an irrational belief in work for the sake of work,” says Benjamin Hannikat, another post-labor future researcher and historian from the University of Iowa, although most of the works are not pleasant. The 2014 Gallup report on job satisfaction says that 70% of Americans are not passionate about their work. Hannikat said that if the cashier’s job was a video game, grab the item, look for the barcode, scan, transfer, repeat, video game critics would call it mindless. And if this is a job, then politicians praise its intrinsic dignity. “Purpose, meaning, identification, realization of possibilities, creativity, autonomy - all these things, which, according to positive psychology, are indispensable for good health, are absent in regular work.”

The researchers of the post-labor future are right about important things. Paid work does not always benefit society. Raising children and caring for the sick is a necessary job, and people pay little or no pay for them. In the post-labor society, according to Hannikata, people could spend more time caring for their family and neighbors, and self-esteem could be born in relationships, not from career achievements.

Agitators for post-work recognize that even at best, pride and jealousy will not disappear, because the reputation is still not enough for everyone, even in an economy of abundance. But with the correctly selected state support, in their opinion, the end of work for wages will mark the golden age of a good life. Hannikat thinks that colleges will be able to become centers of culture, not institutions for preparing for work. The word "school" comes from the Greek "skholē", which means "leisure." “We taught people to spend their free time,” he says. “Now we teach them how to work.”

The Hannikata worldview is based on tax and redistribution assumptions that not all Americans can share. But even if you temporarily leave them, his vision contains problems: it does not reflect the world as most unemployed people see it. Unemployed people do not spend time socializing with friends or starting a new hobby. They watch TV or sleep. Surveys show that middle-aged people out of work devote some of the time they used to give to work, cleaning and caring for children. But men mostly spend their time at leisure, the lion’s share of which is spent on TV, Internet and sleep. Pensioners watch TV 50 hours a week. This means that most of their lives they spend in a dream or sitting on a sofa, looking at the screen. In the case of non-workers, in theory, there is more time for social activity, and, nevertheless, research shows that they feel more isolated from society. It is surprisingly difficult to replace the camaraderie that occurs next to the cooler in the office.

Most people want to work, and feel miserable when they can't. The problem of unemployment extends far beyond the simple loss of income. People who have lost their jobs are more likely to suffer from mental and physical illnesses. “There is a loss of status, malaise, demoralization, which manifests itself somatically and / or physiologically,” said Ralph Catalano, a professor of public health at the Berkeley Institute. Studies show that recovering from a long period of unemployment is harder than from losing a loved one or from serious injury. What helps people recover from emotional traumas — routine, distraction, the meaning of daily activities — is inaccessible to the unemployed.

The transition from labor to resting power will have a negative impact on Americans - these working bees of the rich world: between 1950 and 2012, the number of hours worked per year in Europe dropped dramatically, to 40% in Germany and the Netherlands. At the same time in the United States, it fell by only 10%. More affluent Americans with higher education work more than 30 years ago, especially considering the time spent answering email from home.

In 1989, psychologists Mihaly Cikszentmihai [Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi] and Judith Lefevre [Judith LeFevre] conducted a famous study among Chicago workers, who discovered that people in the workplace often wanted to be somewhere else. However, in the questionnaires the same workers indicated that they feel better and are less worried while in the office or at work than anywhere else. Psychologists have called this the “work paradox”: many people are happier complaining about their work than indulging in too much leisure. Others called the “guilty feeling of a lazy-bastard” effect, in which people use the media to relax, but feel useless when evaluating unproductively spent time. Pleasure is a momentary affair, and pride arises only when assessing past achievements.

Post-labor researchers say that Americans work so much because of their culture, which makes them feel guilty about unproductive time spent, and this feeling will fade away while work will cease to be a normal pastime. Maybe so - but you can not test this hypothesis. Responding to my question about which modern society most resembles the post-worker ideal, Hannikat admitted: “I'm not sure that there is such a place at all”.

There may be less passive and more productive forms of leisure. Perhaps this is already happening. The Internet, social networks and games offer entertainment that is as easy to get involved in as watching TV, but they have more developed goals and less isolate people. Video games, as if they are not ridiculed, allow you to achieve certain achievements. Jeremy Bailenson, a professor of communications at Stanford, says that with the improvement of virtual reality technology, the “cyber existence” of people will become as rich as the “real” life. Games in which “players climb into the skin of another person in order to feel his first-person experiences not only make it possible to live various fantasies, but also help you live the life of another person and teach you empathy and social skills.”

It is difficult to imagine that leisure completely replaces the vacuum of achievements formed during the disappearance of labor. Many need the achievements gained through work to have some kind of goal. To present the future, offering us something more than just every minute satisfaction, we need to imagine how millions of people will be able to find an occupation that is not formally paid. So, inspired by the predictions of the most famous economists of US labor, I made a detour on my way to Youngstown and stopped in Columbus, Ohio.

4. Social creativity: a rematch of artisans

Initially, the middle class of the United States were artisans.Before industrialization swept the economy, many of those who did not work on farms were engaged in jewelry, blacksmithing or woodworking. Industrial production of the 20th century eliminated this layer. But Lawrence Katz, an economist at Harvard Labor, sees the next wave of automation as a force that will give us back art and craftsmanship. Specifically, he is interested in the consequences of the emergence of 3D printers, when automation creates complex objects from digital prototypes.

“A hundred years old factories could produce Model T, forks, knives, cups, glasses according to standard and cheap schemes, and this brought artisans out of business,” Katz told me. - But what if new technologies, such as 3D printers, can produce unique things almost as cheaply? It is possible that information technology and robots will eliminate familiar workplaces, and create a new artisan economy, an economy built around self-expression, in which people will use the time to create art objects. ”

In other words, this future does not promise consumption, but creative expression, due to the fact that technology will return the tools for creating objects back into the hands of individuals, and democratize mass production.

Something similar can already be observed in a small but growing number of creative factories called “makerspace”, arising in the United States and around the world. The idea factory in Columbus [Columbus Idea Foundry] is the largest such place in the country, a former shoe factory, crammed with industrial-era machines. Hundreds of factory members pay a monthly fee for the use of machine tools for the production of gifts and jewelry. They solder, polish, paint, play with plasma cutters and work with grinders and lathes.

When I arrived there on a cold February day, on the slate standing by the door, I saw three arrows pointing to the toilets, casting tin and zombies. Not far from the entrance, three people with stained fingers were repairing a 60-year-old lathe in shirts with oil stains. Behind them, a local artist taught an old woman to transfer photos to a large canvas, and a couple of guys fed pizza with a stone stove, heated by a propane torch. Somewhere nearby, a man in protective glasses was cooking a sign for a local chicken restaurant, others were scoring codes in a CNC laser cutter. Through the noise of drilling and sawing, rock music erupted from the Pandora service, coming from an Edison phonograph connected via WiFi. This factory is not just a set of tools, it is a social center.

Alex Bandar, who founded it after receiving his doctoral degree in materials science and engineering, has a theory about the rhythms of inventions in American history. In the past century, the economy moved from hardware to software, from atoms to bits, and people spent more and more time in front of screens. But gradually, computers took more and more tasks that previously belonged to people, and the pendulum swung back — from bits to atoms, at least with regards to daily human activity. Bandar believes that a digital society will learn to appreciate the pure pleasures of making things that can be touched. “I have always strived to get into a new era in which robots follow our instructions,” says Bandar. - If you create batteries of better quality, improve robotics and manipulators, then you can be asserted with confidence,that robots will do all the work. So what are we going to do? Play? Paint? Are we going to start talking to each other again? ”

You don’t need to have sympathy for plasma cutters to see the beauty of the economy, in which tens of millions of people make things that they like to do - whether they are physical or digital things, whether they do them in special places or online - and in which they get feedback and recognition for their work. The Internet and the abundance of low-cost tools for creating objects of art have already inspired millions of people to create culture right in their living rooms. Every day, people upload more than 400,000 hours of videos on YouTube and 350 million photos on Facebook. The disappearance of the formal economy can liberate many future artists, writers and craftsmen who devote their time to creative interests and produce culture. Such activities lead to the appearance of the very qualitieswhich organizational psychologists consider necessary to obtain job satisfaction: independence, the ability to achieve mastery, purposefulness.

Having walked around the factory, I talked, sitting at a long table, with several of its members, trying a pizza that came out of a stone oven. I asked what they think of their organization as a model of the future, in which automation has advanced even further in the formal economy. Mixed-genre artist Kate Morgan said that most of her acquaintances would quit their jobs and dedicate themselves to the factory if they could do it. Others talked about the need to see the results of their work, which are felt much more in the work of an artisan than in other areas of activity where they tried themselves.

Later we were joined by Terry Griner, an engineer who built miniature steam engines in his garage before he was invited to join Bandar. His fingers were covered with soot, and he told me how proud he was of repairing various things. “I have been working since I was 16 years old. I was engaged in food, worked in restaurants, hospitals, programmed computers. He did a different job, says Greener, at the moment his father is divorced. “But if we had a society that said:“ We will take care of everything that is necessary, and you go, work in a workshop, ”for me it would be a utopia. For me, this would be the best possible world. ”

5. Occasional Earnings: Cope Yourself

Kilometers and a half in the eastern suburbs of Youngstown, in a brick building surrounded by empty parking lots, is the Royal Oaks - a classic eatery for blue-collar workers. At half past five on Wednesday, there was almost no free space. The lights mounted along the wall illuminated the bar with yellow and green. At the far end of the room piled up old bar signs, trophies, masks, mannequins - it all looked like trash left after the party. Most of those present were middle-aged men; some of them were sitting in groups. They talked loudly about baseball and smelled a little marijuana. Some drank at the bar alone, sitting in silence, or listening to music through headphones. I talked with several clients, working musicians, artists or handymen. Many of them did not have a permanent job.

“This is the end of a certain type of work for a salary,” says Hannah Woodruff, the local bartender who turned out to be a graduate of the University of Chicago. She is writing a dissertation on Youngstown as a herald of future work. Many residents of the city, according to her, work under the schemes of "extra wage payments", working for housing, receiving wages in envelopes or exchanging services. Places like Royal Oaks have become new employment services - here people not only relax, but also look for performers of specific works - for example, for car repairs. Others exchange vegetables grown in urban gardens created by enthusiasts among the vacant parking lots of Youngstown.

When a whole region like Youngstown suffers from long and serious unemployment, the problems it causes go far beyond personal - spreading unemployment undermines neighboring areas and draws out their urban spirit. John Rousseau, a professor at Youngstown State University, and co-author of the city’s history, Steeltown USA, said that local self-identification felt a serious blow when residents lost the opportunity to find a reliable workplace. “It is important to understand that this affects not only the economy, but also the psychology of people,” he said to me.

For Rousseau, Youngstown is at the forefront of a large trend to the emergence of a class of “precariats” - the working class, running from task to task in an effort to make ends meet, and suffering from a lack of employee rights, opportunities to bargain for favorable conditions and job guarantees. In Youngstown, many workers resigned to the lack of guarantees and poverty, building an identity and some sort of pride around odd jobs. They lost faith in organizations, in corporations that left the city, the police who could not cope with security, and that faith did not return. But Rousseau and Woodruff both say they are counting on their independence. So the place that once determined its inhabitants with the help of steel learns to appreciate resourcefulness.

Karen Schubert, a 54-year-old writer with two higher educations, took a part-time job as a waitress at Youngstown Cafe after looking for a full-time job for several months. Schubert has two grown children and a grandson, and she says that she really enjoyed teaching writing and writing at a local university. But many colleges replaced full-time professors with part-time adjunct professors to save on expenses, and in her case, the hours of work that she could do at the university were not able to ensure its existence - and she stopped working there. “I think I would take it as a personal failure if I didn’t know how many Americans fell into the same trap,” she said.

Among the precincts of Youngstown, one can see the third possible future, in which millions of people have been trying for years to find the meaning of existence in the absence of formal jobs, and where entrepreneurship arises from necessity. But although there is no comfort in the economy of consumption, or the cultural wealth inherent in the future of the artisans of Lawrence Katz, it is still a more complicated thing than simple dystopia. “Some young people who work part-time in the new economy feel independent, and the proportions of their work and personal relationships are sustained, and they like this state of affairs - not long to have time to concentrate on their hobbies,” says Rousseau.

Salaries Schubert in the cafe is not enough for life, and in her free time she sells her books of poetry at readings, and organizes meetings of the literature and art community of Youngstown, where other writers (many of whom also do not work full time) share their prose. Several local people confessed to me that the disappearance of work enriched the local musical and cultural environment, as creative people had enough opportunities to spend time with each other. “We are a terribly poor population, but the people living here are not afraid of anything, they have creative potential and they are just phenomenal,” says Schubert.

A person has creative ambitions, like Schubert, or not - it is becoming easier to find a temporary part-time job. Paradoxically, it's all about technology. The constellation of Internet companies compares the available workers with small temporary jobs, including Uber for drivers, Seamless for food delivery, Homejoy for housekeeping, and TaskRabbit for everything else. The online markets of Craigslist and eBay made it easier for people to engage in small independent projects, such as furniture restoration. And although the economy "to order" has not yet become an important part of the overall picture of employment, according to statistics from the labor bureau, the number of services for finding temporary part-time jobs has increased by 50% since 2010.

Some of these services may also be selected by machines over time. But applications for providing work to order also divide the work, like the work of a taxi driver, into smaller tasks, such as one trip. This allows a large number of people to compete for smaller pieces of work. These new features are already testing the legal definitions of the employer and the employee, and there are already enough contradictions in these terms. But if in the future the number of full-time jobs will decrease, as happened in Youngstown, the division of the remaining work among many part-time workers will not necessarily become an undesirable development of events. Do not rush to flay companies that allow people to combine their work, art and leisure activities in ways that they like.

Today, the presence and absence of work are perceived as black and white, binary, and not as two points at different ends of a wide range of possibilities. Until the mid-19th century, the concept of unemployment did not exist in the United States at all. Most people lived on farms, and if paid work appeared or disappeared, the home industry — canning, sewing, carpentry — was a constant thing. Even in the worst times of economic panic, people found something productive that they could do. The despair and helplessness of unemployment were discovered, to the dismay of cultural critics, only after the work in the factories began to prevail, and the cities - to grow.

The 21st century, if it has fewer full-time jobs in those sectors that can be fully automated, may become similar to the mid-19th century: the economic market from occasional jobs in a wide range of areas, the loss of any of which does not suddenly lead a person to full stop. Many fear that intermittent employment is a deal with the devil, when autonomy is increased by reducing security. But someone can thrive in a market where versatility and dexterity are rewarded - where, as in Youngstown, there are few jobs, but a lot of work.

6. Government: visible hand

In the 1950s, Henry Ford II, director of Ford, and Walter Reuther, head of the auto industry union, studied the new engine factory in Cleveland. Ford pointed to a large number of automatic machines and said: "Walter, how are you going to make these robots pay union dues?" The head of the union said, "Henry, how are you going to get them to buy your cars?"

As Martin Ford (not a relative) writes in his book: The Rise of the Robots, although this story may be apocryphal, its moral is instructive. We quickly notice the changes that occur when replacing workers with robots - for example, fewer people in the factory. But it is more difficult to notice the consequences of this transformation, for example, the effect of consumer extinction on the consumption economy.

Technical progress on the scale we are discussing will lead to such social and cultural changes that we simply cannot assess. Imagine how thoroughly the work has changed the geography of the United States. Today’s coastal cities are crowded office buildings and apartments. They are expensive and stand in cramped. But reducing the amount of work can make office buildings unnecessary. How will urban landscapes respond to this? Do offices migrate to apartments, allowing more people to live comfortably in city centers, and preserve the urban landscape? Or will we see empty shells and the spread of decline? Will large cities be needed if their role as very complex labor ecosystems diminish? After the 40-hour work week has died, the idea of long journeys to and from work twice a day will seem to future generations as an old-fashioned loss of time. Will these generations prefer living on streets full of tall buildings, or in small towns?

Today, many working parents worry that they spend too much time in the office. With the decline of full-fledged work, taking care of children will become less difficult. And since historically the migration to the United States was due to the emergence of new jobs, it may also decrease. Diasporas of large families can give way to closer clans. But if men and women lose the meaning of life and the dignity of the work they do will disappear, the problems in these families will remain.

The collapse of the workforce will lead to major policy debates. Debates on income taxes and income distribution may be the most important in history. In his book “A Study on the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,” Adam Smith spoke of the “invisible hand of the market,” referring to order and social benefits, miraculously arising from the egoism of individuals. But in order to preserve the consumer economy and social ties, governments will have to accept what Haruhiko Kuroda, the head of the Bank of Japan, called "the visible hand of economic intervention." This is how it can work in the short term.

Local governments can create increasingly ambitious community centers or other public places where local people can meet, gain skills, develop connections around sports activities or crafts, and socialize. The two most common side effects of unemployment are the loneliness of individuals and the disappearance of the foundation of public pride. State policy that directs money to areas of economic distress can heal diseases from idleness and form the basis of a long-term experiment to involve people in their environment in the absence of full-fledged work.

You can also make it easier for people to open their own small businesses. Over the past few decades, in all states, small business is experiencing a decline. One way to fuel new ideas would be to build a network of business incubators. Youngstown offers an unexpected model: his business incubator is internationally recognized, and his success has brought new hope to the main street of the city.

At the beginning of every decline in the availability of jobs, the United States could learn from Germany in the area of job separation. The German government allows firms to cut working hours for their employees, instead of firing them in difficult times. A company of 50 people instead of laying off 10 people can reduce the working hours of all employees by 20%. Such a policy could help employees of trustworthy firms retain their belonging to the labor force, despite the decreasing overall amount of work.

This smearing work has limitations. Some posts cannot be separated so easily, and in any case, the division will not stop the squeezing of the working pie - it will only distribute the shares differently. In the end, Washington will need to distribute wealth.

One way is to impose a large tax on the proportion of income going to capital owners and use the money to distribute to the adult population. This idea, called the "universal basic income" has received the support of both parties in the past. She is supported by many liberals, and in the 1960s Richard Nixon and conservative economist Milton Friedman proposed their own versions of the idea. Despite the story, the universal income policy in the world without universal work inspires fear. The rich can say that their hard work subsidizes millions of loafers. Moreover, although unconditional income can replace lost wages, it can offer little to replace the social benefits of work.

The easiest way to solve the last problem is if the government pays people to do at least something. And although it smacks of old European socialism, or a concept from the era of the Great Depression about the invented work “makework”, it can do a lot to preserve responsibility, human activity, active labor. In the 1930s, the US Public Works Administration (Works Progress Administration, WPA) not only rebuilt the public infrastructure. She hired 40,000 artists and other cultural workers to compose music and theatrical productions, write murals and paintings, travel guides to states and districts, and collections of records. You can imagine the same technique, or even something more extensive, used in a world that has experienced universal employment.

And how can it look like? Several government projects may justify hiring directly, for example, to care for a growing number of older people. But if the balance of work goes down to small-scale, sporadic employment, it is easiest for the government to help everyone stay busy by organizing the state-run online market (or a series of local markets organized by local authorities). People could search for more and long-term projects, such as cleaning after a disaster, or short-term - an hour of teaching, an evening of entertainment, hiring to create a work of art. Requests could come from local authorities, associations or non-profit groups, from wealthy families looking for nannies or tutors, or from other people who have the opportunity to spend on the site some "loans". To ensure a basic level of labor force participation, the government could pay adults a single amount in exchange for minimal activity on the site, but people could always earn more by doing more errands.

Although the digital “Public Works Office” may seem strange anachronism, it will be similar to the state version of the Mechanical Turk service, one of the Amazon projects, where individuals and companies place orders of varying complexity, and so on. "Turks" choose their job and get paid for their implementation. The service is intended for tasks that the computer cannot perform. He was named in honor of the Austrian scam of the 18th century, when in the machine, which allegedly skillfully played chess, hid the man who ran it.

The government market can also specialize in tasks that require empathy, humanity, or an individual approach. Joining millions of people in one knot, he can inspire what technology writer Robin Sloan called "the Cambrian explosion of mega-scale creative and intellectual tasks, the generation of Wikipedia-class projects that may ask their users for even greater involvement."

It is necessary to clarify the use of government tools to create other incentives, to help people avoid typical unemployment traps, and to build eventful lives and living communities. After all, the members of the Columbus idea factory did not have an innate love of working on a lathe or cutting with a laser. Mastering these skills requires discipline, which requires education, which, for many, requires guarantees that hours spent in practice, often frustrating, will eventually be rewarded. In a job-deprived society, financial rewards for education and training will not be so obvious. Here is one of the difficulties that arise when trying to imagine a prosperous society without work: how will people discover their talents, or enjoy learning skills, if they have no incentive to develop this or that?

Consideration should be given to making small payments to young people for attending and graduating from a college, skills training programs, or visiting community workshops. This sounds radically, but the goal of this idea is conservative: to preserve the status quo of an educated and involved society. Whatever their career opportunities, young people will grow and become citizens, neighbors, and sometimes workers. Pushing to education and training can be especially useful for men, as they are more susceptible to staying within the four walls after losing their jobs.

7. Jobs and vocations

In a few decades, historians will regard the 20th century as a deviation due to its religious commitment to recycling during prosperity, due to the weakening of the family in order to please working opportunities, due to the identification of income with self-esteem. The society I’ve described, which got rid of work, looks at today's economy through a twisted mirror, but in many aspects it reflects the forgotten norms of the 19th century - the middle class of artisans, the superiority of local communities, and the absence of universal unemployment.

Three different futures: consumption, community creativity and odd jobs - these are not different ways, branching off from today. They will intertwine and influence each other. Entertainment will become more diverse and attract people who have nothing to do. But if only this happens, then the society will lose. The Columbus factory shows how “third places” in people's lives (communities separate from homes and workplaces) can be the basis for growth, learning new skills, and opening up their hobbies. With or without them, many will have to come to terms with the ingenuity acquired over time by cities such as Youngstown, which, even if they look like museum exhibits telling about the old economy, can predict the future of many cities that await them in the next 25 years.

On the last day of my stay in Youngstown, I met with Howard Jesco, a 60-year-old graduate of Youngstown State University, for a burger at a diner located on the main street. A few months after Black Friday 1977, ending with the state university in Ohio, he spoke on the phone with his father, who was then working in the manufacture of hoses and cable channels near Youngstown. “You should not worry about returning here in search of work,” his father told him. “Here it is no longer there.” Years later, Jesco returned to Youngstown to sell waterproofing systems to construction companies, but he recently quit. His clients were crushed by the Great Recession and they already bought very little. This coincided with a knee replacement surgery due to degenerative arthritis, with the result that he had 10 days in a hospital bed to think about the future. Jesco decided to go back to school and become a teacher. “My real vocation,” he says, “has always been to educate people.”

One of the theories of work claims that people see themselves through work, career and vocation. Those who say that “they only do their work” emphasize that they work for money, and do not aspire to some kind of lofty goal. Pure careerists concentrate not only on income, but also on status that comes with promotions and popularity among colleagues. But a person seeks his own recognition not only because of salary and status, but also because of internal satisfaction from work.

Thinking about the role that work plays in people's self-esteem, especially in the United States, I perceive the prospects for the future without work to be hopeless. No single income will prevent the decline of a country in which several people work to subsidize the idleness of tens of millions. But the future without work still holds a glimmer of hope, because the need to work for wages prevents many people from looking for an occupation that they could enjoy.

After talking to Jesco, I walked back to my car to leave the city. I thought about the life of Jesco, what it could be if the city factory had not given way to a steel museum. If the city continued to offer stable and predictable jobs to its residents. If Jesco went to work in the steel industry, he would have been preparing for his retirement. But the industry collapsed, and after years, a new recession struck. As a result of all these tragedies, Howard Jesco does not retire at 60. He gets a diploma to become a teacher. So many jobs have been lost to make him strive for what he always wanted.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/372307/

All Articles