Ask Ethan: What are the quantum causes of sodium reacting with water?

If you put a piece of sodium in water, you can cause a violent, often explosive reaction.

Sometimes we learn something at the beginning of life and just take it for granted that the world works that way. For example, if you throw a piece of pure sodium into water, you can get a legendary explosive reaction. As soon as a piece gets wet, the reaction causes it to sizzle and warm up, it jumps over the surface of the water and even gives out tongues of flame. This, of course, is just chemistry. But isn't something else happening at a fundamental level? This is exactly what our reader Semen Stopkin from Russia wants to know:

What forces drive chemical reactions, and what happens at the quantum level? In particular, what happens when water interacts with sodium?

')

The reaction of sodium with water is a classic, and it has a deep explanation. Let's start with studying the passage of the reaction.

The first thing you need to know about sodium is that at the atomic level it has only one proton and one electron more than that of an inert, or noble gas, neon. Inert gases do not react with anything, and all due to the fact that all their atomic orbitals are completely filled with electrons. This ultra stable configuration collapses when you go one element further in the periodic table, and this happens with all the elements that demonstrate similar behavior. Helium is superstable, and lithium is extremely chemically active. Neon is stable, and sodium is active. Argon, krypton and xenon are stable, but potassium, rubidium and cesium are active.

The reason is an extra electron.

The periodic table is sorted by periods and groups according to the number of free and occupied valence electrons - and this is the first factor in determining the chemical properties of the element.

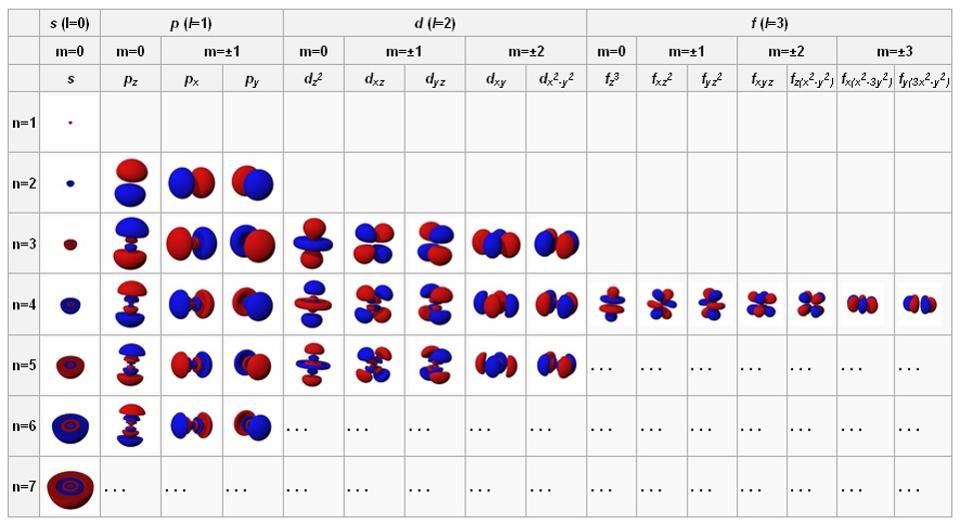

When we study atoms, we get used to consider the nucleus as a solid, shallow, positively charged center, and electrons as negatively charged points in an orbit around it. But this is not the end of quantum physics. Electrons can behave like points, especially if you shoot them with another high-energy particle or photon, but if left alone, they spread out and behave like waves. These waves are capable of self-tuning in a certain way: spherically (for s-orbitals containing 2 electrons each), perpendicularly (for p-orbitals containing 6 electrons each), and further, to d-orbitals (10 electrons each), f-orbitals ( on 14), etc.

The orbitals of atoms in the state with the lowest energy are at the top left, and as they move to the right and down, the energy grows. These fundamental configurations govern the behavior of atoms and intra-atomic interactions.

These shells are filled due to the Pauli prohibition principle , which forbids two identical fermions (for example, electrons) to occupy the same quantum state. If an electron orbital is filled in an atom, then the only place where an electron can be placed is the next, higher orbital. The chlorine atom will gladly accept an additional electron, since it lacks only one to fill the electron shell. And vice versa, the sodium atom will gladly give away its last electron, since it is superfluous in it, and all the others fill the envelopes. Therefore, sodium chlorine is so good and it turns out: sodium gives an electron to chlorine, and both atoms are in an energetically preferable configuration.

Elements of the first group of the periodic table, especially lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, etc. lose their first electron much lighter than everyone else

In fact, the amount of energy required for an atom to give up its external electron, or ionization energy, turns out to be particularly low in metals with one valence electron. From the numbers it is clear that it is much easier to pick up an electron from lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, cesium, etc., than from any other element.

Frame from animation showing the dynamic interaction of water molecules. The individual H 2 O molecules are V-shaped and consist of two hydrogen atoms (white) connected to an oxygen atom (red). Neighboring molecules of H 2 O react briefly with each other through hydrogen bonds (blue-white ovals)

So what happens in the presence of water? You can think of water molecules as extremely stable - H 2 O, two hydrogen, associated with the same oxygen. But the water molecule is extremely polar - that is, on one side of the H 2 O molecule (on the side opposite to two hydrogens), the charge is negative, and on the opposite side - positive. This effect is enough for some water molecules - of the order of one in several millions - to break up into two ions - one proton (H + ) and hydroxyl ion (OH - ).

In the presence of a large number of extremely polar water molecules, one of several million molecules will break up into hydroxyl ions and free protons - this process is called autoprotolysis.

The consequences of this are quite important for such things as acids and bases, for the processes of dissolving salts and activating chemical reactions, etc. But we are interested in what happens when sodium is added. Sodium — this neutral atom with one poorly holding external electron — falls into water. And these are not just neutral H 2 O molecules, they are hydroxyl ions and individual protons. First of all, protons are important to us - they bring us to the key issue:

What is energetically preferable? Have a neutral sodium atom Na together with a separate proton H +, or a sodium ion that has lost an electron Na + together with a neutral hydrogen atom H?

The answer is simple: in any case, the electron will jump from the sodium atom to the very first separate individual proton that gets in its way.

Having lost an electron, sodium ion will gladly dissolve in water, as does chlorine ion, acquiring an electron. It is much more beneficial energetically - in the case of sodium - that the electron mates with a hydrogen ion

That is why the reaction takes place so quickly and with such an energy output. But that is not all. We got neutral hydrogen atoms, and, unlike sodium, they do not line up in a block of individual atoms bound together. Hydrogen is a gas, and it enters an even more energetically preferable state: it forms a neutral hydrogen molecule H 2 . As a result, a lot of free energy is formed, which goes to the heating of the surrounding molecules, neutral hydrogen in the form of a gas that escapes from the liquid solution to the atmosphere containing neutral oxygen O 2 .

A remote camera shoots near the main Shuttle engine during a test run at the John Stennis Space Center. Hydrogen is the preferred fuel for missiles due to its low molecular weight and excess oxygen in the atmosphere with which it can react.

If you accumulate enough energy, hydrogen and oxygen will also react! This violent burning produces water vapor and a tremendous amount of energy. Therefore, when a piece of sodium (or any element of their first group of the periodic table) enters the water, an explosive release of energy occurs. All this is due to electron transfer, controlled by the quantum laws of the Universe, and the electromagnetic properties of charged particles that make up atoms and ions.

The energy levels and wave functions of electrons correspond to different states of the hydrogen atom — although almost the same configurations are inherent in all atoms. Energy levels are quantized by a multiple of Planck’s constant, but even the minimum energy, the ground state, has two possible configurations, depending on the spin ratio of the electron and proton

So again, what happens when a piece of sodium falls into the water:

- sodium immediately gives away an external electron to the water,

- where it is absorbed by the hydrogen ion and forms neutral hydrogen,

- this reaction releases a large amount of energy, and warms the surrounding molecules,

- neutral hydrogen is converted to molecular hydrogen gas and rises from the liquid,

- and, finally, with sufficient energy, atmospheric oxygen enters into a combustion reaction with hydrogen gas.

Metallic Sodium

All this can be simply and elegantly explained with the help of the rules of chemistry, and this is how they often do. However, the rules governing the behavior of all chemical reactions come from even more fundamental laws: the laws of quantum physics (such as the Pauli exclusion principle governing the behavior of electrons in atoms) and electromagnetism (controlling the interaction of charged particles). Without these laws and forces there will be no chemistry! And thanks to them, every time you drop sodium into the water, you know what to expect. If you still do not understand - you need to put on protection, do not take sodium by hand and move away when the reaction starts!

Ethan Siegel - astrophysicist, popularizer of science, blog Starts With A Bang! He wrote the books Beyond The Galaxy , and Treknologiya: Star Trek Science [ Treknology ].

FAQ: if the universe is expanding, why aren't we expanding ; why the age of the universe does not coincide with the radius of the observed part of it .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/371251/

All Articles