NASA has proven that it can navigate in space using pulsars. Where are we going now?

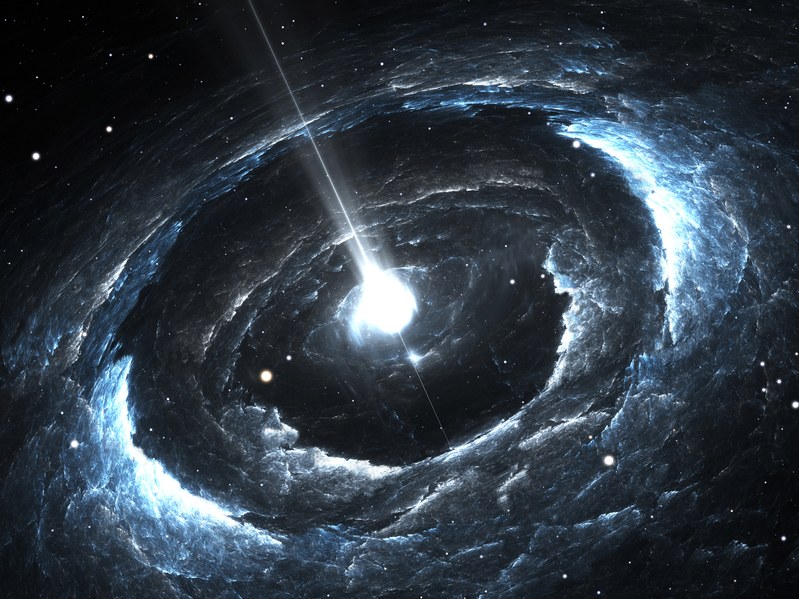

Half a century ago, astronomers saw the first pulsar: a dead, remote, absurdly dense star, radiating pulses with remarkable constancy. The object signal was so persistent that astronomers jokingly christened it LGM-1 (little green men).

Soon, scientists found more signals of this type. This reduced the likelihood that these impulses were the work of intelligent aliens. But fixing other pulsars gave another opportunity: probably objects like the LGM-1 can be used to navigate in deep space, which future space missions may need. The idea was that with the right sensors and navigation algorithms on board, the spacecraft would be able to independently determine its position in space, measuring the received signals from several pulsars.

The concept was so attractive that when developing the gold plates placed on board the Pioneer ship, Karl Sagan and Frank Drake decided to mark the location of our solar system relative to 14 pulsars. “Even then, people understood that pulsars can be used as beacons,” says Kif Gendero, an astrophysicist from the Goddard Space Flight Center at NASA. But for decades, navigating through the pulsars has remained just a fascinating theory — a way of orientation provided for space operas and Star Trek episodes.

')

However, in mid-January, Gendero and the NASA research team announced that they finally proved the ability of the pulsars to play the role of a space navigation system. They quietly performed this demonstration in November 2017, when the Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer, NICER, a pulsar measuring instrument the size of a washing machine brought onboard the ISS, spent a couple of days watching the electromagnetic radiation of five pulsars. With the help of the “Sextant” improvement [Station Explorer for X-ray Timing and Navigation Technology, SEXTaNT - navigation based on pulsar X-rays] Nyser was able to determine the location of the station in Earth orbit with an accuracy of 4 km - while moving at a speed of more than 27 000 km / h

But the greatest advantages of navigation through the pulsars will be felt not in the Earth’s orbit (there are better and more accurate ways of tracking the ship), but further in space. Today’s space missions are guided by the global Deep Space Network (DSN) radio antenna system - a network of far-space communications. “DSN gives you very good distance information,” says Gendero, who was the main investigator for the Neiser mission. “If you know the speed of light and you have a very accurate clock, it can send a signal to the ship and calculate the distance to it with high accuracy.”

But DSN has serious limitations. The farther the ship flies away, the less reliable the measurement is; the network measures well the distance, but doesn’t determine the deviation of the ship poorly. On long-range missions, it also takes more time to travel radio waves to earthly communications and to transmit instructions from the mission planning center, due to which the response speed drops to a few minutes, hours or even days. Moreover, the network quickly becomes saturated; it looks like an overloaded WiFi connection - the more ships build a course in the depths of space, the smaller the DSN's bandwidth shares will be able to give them.

Pulsar navigation should eliminate all the shortcomings of DSN, especially in the area of bandwidth. A spacecraft equipped with everything to scan for pulsar beacons can calculate its absolute position without any connection with the Earth. This will free up the DSN pass band and valuable maneuver time in space.

“It comes down to the letter A: autonomy,” says Jason Mitchell of NASA, an aerospace technologist at Goddard and project manager at SEXTANT. When a spacecraft is able to determine its position in space, regardless of the infrastructure on Earth, “this gives an opportunity for people planning a mission to think about navigation in places where they could not navigate differently,” he says. Pulsar navigation can allow a spacecraft to perform maneuvers, for example, behind the Sun (signals from and to DSN cannot pass through the Sun). In the distant future, missions on the borders of our solar system and beyond - for example, in the Oort cloud - will be able to maneuver in real time on the basis of independently determined coordinates, without waiting for instructions from the Earth.

But pulsars are not the only way to orient themselves in a distant solar system. Joseph Guinn, an expert in deep-space navigation at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who is not associated with Neiser, is developing an autonomous system that can use cameras to detect objects, using their position to determine their coordinates. He calls this system the deep-space positioning system (DPS). It works through the use of reflection from cosmic stones in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. These reflections repeat the scheme of the global GPS positioning system, a network of satellites located at an altitude of 20180 km in orbit around the Earth. Its main advantage is that it is able to inform the spacecraft of its location relative to the object of interest. Pulsar navigation can only tell the ship its absolute location in space. Imagine this: Pulsar navigation can tell if you are inside your office building, and DPS can tell you if your boss is not behind you.

But DPS has its drawbacks. Like GPS, the DPS system loses its reliability if you fly out of its limits. “If you get far enough into the depths of the solar system, where nothing is visible due to the small amount of light, you can find yourself in a position where the navigation through the pulsars is your only opportunity,” Guinn says. After all, pulsars are located very far outside our solar system; "You do not need to worry about not going beyond them."

The ideal solution would be to equip a spacecraft with instruments for various types of navigation: transmitters and receivers for communication with DPS on Earth; DPS; high-precision sensors like Naicer to detect and measure the arrival time of pulsar signals. If the DSN is overloaded, or if the ship needs to navigate autonomously and in real time, the DPS may be operational. If it is too dark for her, pulsars take over. When one system fails or reaches its limits, the other system takes its place.

In critical systems such as navigation, redundancy is extremely important. “A good feature of pulsar navigation is that it works completely independently of all other navigation methods, and this can be very valuable,” Gendero says. This is probably why, according to him, people who are planning missions have shown interest in plans to add navigation through the pulsars to the Orion spacecraft , which they will develop to send people into space further than any other means of transportation in history. Guinn says that plans are also being made to equip the Orion with a DPS system, and SpaceX is also interested in it.

The problem with redundancy is to find a place on the ship for all this equipment. In space missions, every gram is important. More weight requires more fuel, and more fuel requires more money. The observatory itself "Nicer" is comparable in size with a washing machine. If the navigation through the pulsars wants to earn a place on the transport ships heading into deep space, she will have to lose a few kilograms.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/371193/

All Articles