New nanodevices from RNA can perceive and analyze many complex signals in living cells

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is used to create logic circuits that can perform various calculations. In the new experiments, Green and his colleagues turned on RNA logic gates in live bacterial cells that act like tiny computers. Image: Jason Drees for the Institute of Biodesign

The combination of biology and technology, known as synthetic biology, is developing very rapidly, opening up new perspectives that one could hardly have imagined until recently.

')

In a new study, Alex Green, a professor at the ASU Biodesign Institute, demonstrates how living cells can be used to perform calculations, like tiny robots or computers.

The results of the new research are very important for intelligent design and targeted drug delivery, green energy production, low-cost diagnostic technologies and even the development of futuristic nanomachines that can hunt for cancer cells or turn off aberrant genes.

“We use easily predictable and programmable RNA-RNA interactions to customize the circuits,” says Green. "This means that we can use computer software to develop RNA sequences that behave the way we want, which makes the design process much faster."

The study appeared in the online edition of the journal Nature .

Projected RNA

The described approach uses schemes consisting of ribonucleic acid or RNA. These schemes, similar to ordinary electronic circuits, self-organize in bacterial cells, which allows them to perceive incoming messages and respond to them, creating a definite conclusion (in this case, a protein).

In the new study, specialized circuits, known as logic gates, were developed in the laboratory and then incorporated into living cells. Tiny switches are triggered when messages (in the form of RNA fragments) are attached to their complementary sequences in the circuit, activating the logic gate and creating the desired output.

RNA switches can be combined in various ways to create more complex logic elements that can evaluate and respond to multiple inputs, just as a regular computer can accept several variables and perform successive operations, such as addition and subtraction, to obtain the final result.

New research has greatly increased the ease of performing cellular calculations. RNA approach to the production of cellular nanodevices is a significant step forward, as they previously required the use of complex mediators, such as proteins. Now the necessary components of the ribbing computer can be easily developed on a regular computer. The pairing of the four letters RNA (A, C, G and U) ensures predictable self-assembly and functioning of these parts in a living cell.

Green's work in this area began at the Weiss Institute at Harvard, where he helped develop the central component used in cellular circuits, known as the toehold RNA switch. The work was done while Green was a postdoc who worked with nanotechnology expert Peng Yin, along with synthetic biologists James Collins and Pamela Silver, who are co-authors of the new article. “The first experiments were in 2012,” says Green. "In principle, the toehold switches worked so well that we wanted to find a way to best use them for cellular applications."

The video demonstrates the basic principles of the RNA toehold switch. Video source: Arizona State University

Upon arrival at ASU, Duo Ma, Green's first graduate student, worked on experiments at the Institute of Biodesign, and another postdoc, Jongmin Kim, continued similar work at the Weiss Institute. Both are co-authors of the new study.

Biological Pentium

The ability to use DNA and RNA, life molecules, to perform computer calculations was first demonstrated in 1994 by Leonard Adleman of the University of Southern California. Since then, progress has progressed significantly, and recently such molecular calculations have been carried out in living cells. (Bacterial cells are usually used for this purpose, as they are simpler and easier to manipulate).

The technique described in the new article uses the fact that RNA, unlike DNA, is single-stranded when it is produced in cells. This allows researchers to create RNA schemes that can be activated when the complementary RNA strand binds to the open RNA sequence in the designed scheme. The binding of complementary strands is regular and predictable, with adenine always mating with uracil, and cytosine with guanine.

With all the elements of the scheme created using RNA, which can accept an astronomical number of possible sequences, the real power of the newly described method lies in its ability to perform many operations simultaneously. Parallel processing provides faster and more complex calculations with efficient use of limited cell resources.

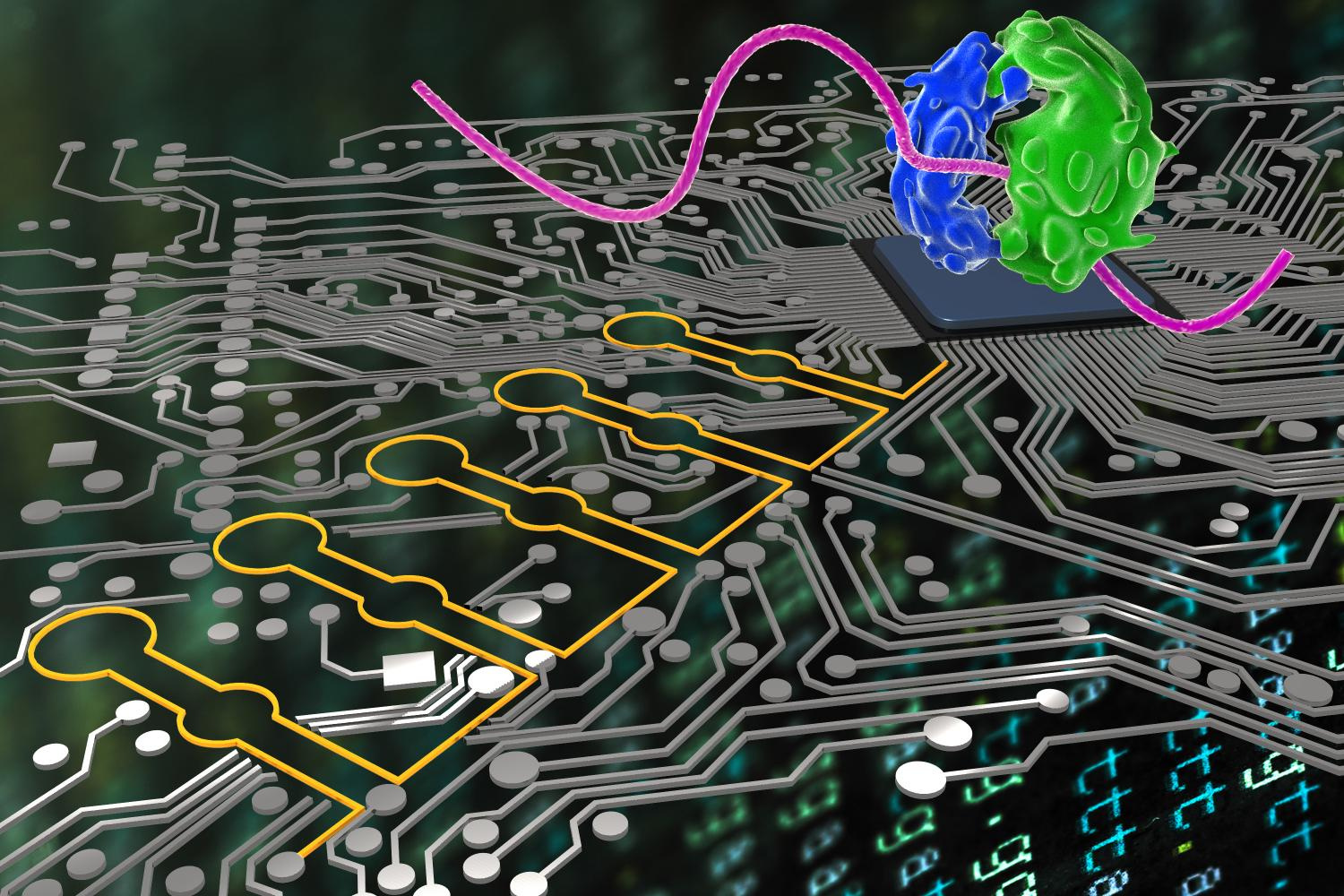

Just as computer scientists use logical language to make their programs do accurate AND, OR, and NOT operations, ribocomputers (colored yellow), developed by a team at the Weiss Institute, can now be used by synthetic biologists to obtain and interpret multiple signals in the cells and instruct their ribosomes (stained blue and green) in order to produce various proteins. Authors: Weiss Institute at Harvard University

Logical results

In the new study, logic gates were developed, known as AND, OR and NOT. AND triggers output in a cell only when two messages, A and B RNA, are present. The OR gate responds either to A or B, while NOT blocks output if the RNA molecule is present. Combining these gates results in complex logic capable of responding to multiple inputs.

Using the toehold RNA switches, the researchers released the first ribo computer devices, with four AND inputs, six OR inputs, and 12 inputs capable of performing a complex combination of AND, OR, and NOT, known as the normal disjunctive form. When the logic gate meets the correct RNA sequences leading to activation, the toehold switch opens and the protein translation process takes place. All of these detection and output functions can be integrated into one molecule, which makes the systems compact and easy to implement in a cell.

The study is the next stage of the current work on the use of universal switches RNA toehold. In earlier papers, Green and his colleagues demonstrated that an inexpensive array of toehold RNA switches can act as a highly accurate platform for diagnosing the Zika virus. Detection of viral RNA in an array activated toehold switches, causing the production of a protein that was recorded as a color change in the array.

The basic principle of using RNA-based devices to regulate protein production can be applied to almost any RNA input, marking a new generation of accurate, inexpensive diagnostics for a wide range of diseases. The cell-free approach is particularly well suited for new threats and during disease outbreaks in the developing world, where medical resources and personnel may be limited.

Computer inside

According to Green, the next phase of research will focus on using RNA toehold technology to create neural networks in living cells. Neural networks are able to analyze the range of excitatory and inhibitory signals, averaging their values and producing a signal for output if a certain threshold of activity has been crossed, just as in normal neurons. Ultimately, researchers hope to induce cells to communicate with each other through programmed molecular signals, forming a truly interactive, brain-like network.

“Since we use RNA, the universal molecule of life, we know that these interactions can also work in other cells, so our method provides a general strategy that can be transferred to other organisms,” says Green, referring to the future in which human cells become fully programmable objects with advanced biological capabilities.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/370717/

All Articles