How to treat crazy. 1.2 - Pharmacotherapy: depression and antidepressants

This article is a logical continuation of the previous post on the device of the brain, schizophrenia and methods of dealing with it. Before reading the following text, it makes sense to get acquainted with the contents of the previous part , without this it can be incomprehensible.

tl; dr : The article talks about depression, that it represents itself at the level of psychopharmacology, as well as some of the drugs used to treat it.

')

Disclaimer : as always, the author warns readers that he is not a psychiatrist, but crazy, and the information presented in this article can in no case be used as a basis for making diagnoses and making decisions about starting, stopping or changing the order of taking any medications. . Medical appointments should be made by a qualified doctor, and for any questions regarding treatment, it makes sense to contact him for advice.

Nevertheless, the author of the article tried many of the described drugs on himself, and also observed their effect on fellows in misfortune, therefore the main theses of the article are confirmed not only by sources, but also [obviously irrelevant [4], but alive] by personal experience.

Interested please under the cat.

Affective disorders

They are mood disorders . The ICD go under the numbers F30 - F39 [5]. They include depression, mania, and their alternation (BAR, cyclotime, etc.). In spite of seeming differences (those who saw depressive and manic patients certainly note how different everything is - appearance, thinking, behavior), there are quite a lot in common: firstly, they cause the patient’s mood to become inadequate, secondly, they have a similar pharmacological nature and, accordingly, are often treated with the same drugs, thirdly, they can “flow” from one to another (for example, what was incorrectly diagnosed as a depressive episode - F32, may the very d le bar be - F31).

Therefore, we will consider them all in one section, paying attention to differences where necessary. As part of this post, we will look at depression, and leave other affective disorders as the topic of future articles.

Depression

Perhaps the most famous of affective disorders. Like many other terms from psychiatry, the word “ depression ” has found quite a wide use in the spoken language [6], where it lost its terminological accuracy: “Ah, I have depression,” the young ladies languidly sigh, “yesterday he left me.”

Surprise for many will be the fact that the absolute majority of cases of the use of this term in everyday life - is incorrect. Depression is not a bad mood , not grief, not depression or fatigue. All of the above may be symptoms of depression, but does not constitute its essence [7].

The classic definition of depression suggests the presence of so-called. " Depressive triad " [8]. Its first component is anhedonia - a decrease in the ability to enjoy: what a person liked before, ceases to like and delight: neither sleep, nor food, nor sex, nor career achievements - nothing causes an emotional lift, nothing is subjectively significant and desirable .

The second component is a violation of thinking . These are not those thinking disorders that occur in schizophrenia, but their own, specifically depressive. First, in cases of severe depression, a decrease in the rate of thinking is usually observed. Secondly, certain patterns of thinking are characteristic of depression, which determine the pessimism of judgments and their self-accusatory nature.

The third component is the motor inhibition : the patient is hard, slowly and reluctant to move.

It should be noted that there are patients in whom not all components of the triad are clearly expressed, but which, nevertheless, suffer from depression in one form or another [9]. Personally, I’m close to the position of Beck, who considers cognitive distortions as the main and decisive component of depression [10], and derives all other features from them.

How does depression differ from grief and other unpleasant, but normal states? Its inadequacy. The fact is that, in itself, grief is not necessarily something pathological, and can be a completely adequate response to events that have occurred [6]. For example, if a person’s beloved hamster died to which he was tied, the presence of signs of a depressive triad within a few days after this event is not a reason to say that he (the person) suffers from depression.

However, if years have passed since the unpleasant event, a man started a new hamster a long time ago, his daughter happily married and gave birth to a grandson, the man himself was recently promoted at his beloved work, and he successfully completed a difficult project, but all his thoughts still revolve around a deceased pet. he spends all his days accusing himself and nothing gives him pleasure, and getting out of bed in the morning was insanely difficult, it makes sense to send such a person to a specialist: it is quite possible that he developed depression.

A good video on what depression is on TED-ED:

Now that we have determined what constitutes depression, we can talk about its causes. In this article, we will not consider the psychological aspects of depression (about this in the next articles), but focus on the biochemistry of the brain.

As often happens in psychiatry, there is still no consensus on what depression is at the neurochemical level [9]. There are only a number of more or less common hypotheses and evidence in favor of each of them.

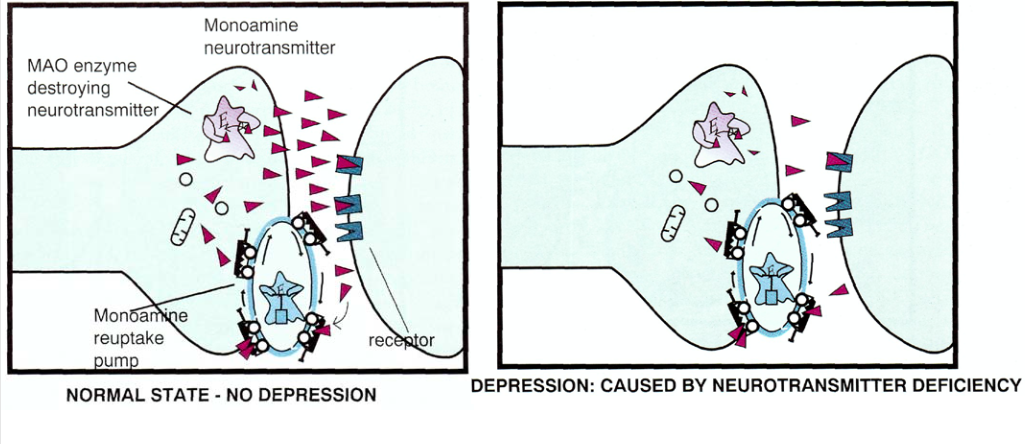

Historically, the first was the assumption that depression is directly linked to the lack of certain neurotransmitters , in particular serotonin and norepinephrine [7,9].

The reasons for proposing this hypothesis are fairly simple and transparent: drugs that affect the reuptake, release or destruction of these neurotransmitters lead to an improvement in the condition of at least some depressed patients.

And drugs that reduce the amount of serotonin and norepinephrine, on the contrary, cause depressive symptoms.

The monoamine hypothesis can be visually represented as the following picture, in the left part of which the normal state is displayed, and in the right part - depression (the neurotransmitter is shown as triangles):

In the last article, when it came to schizophrenia, we talked mainly about dopamine, but now it’s about serotonin and norepinephrine .

Let's start with the last one. So, we have noradrenergic neurons in our brain, i.e. those that use the neurotransmitter norepinephrine as a signal transducer. The main accumulation of such neurons in the brain is the so-called. bluish spot (locus coeruleus) [11]:

It is part of the reticular formation and is located in the brainstem at the level of the bridge. The axons of its neurons go back to the upper layers of the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, septum, striatum, cerebellar cortex. Descending projections go into the spinal cord to sympathetic and motoneurons.

Some of these projections (processes of neurons from a bluish spot extending to other areas of the brain) are of great importance in the formation (and treatment) of depressive symptoms.

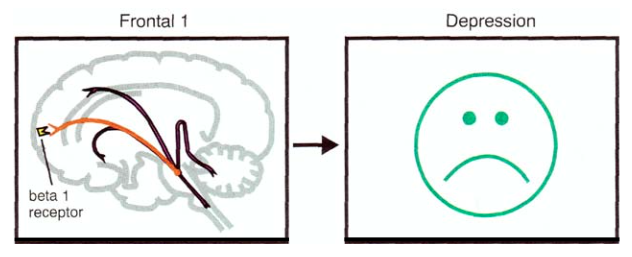

For example, one of the projections into the prefrontal cortex of the brain is responsible for the regulation of mood [9]:

Another - for the effect of norepinephrine on attention:

Projection into the limbic system affects emotions, energy, fatigue, and psychomotor activity:

The projection to the cerebellum may be responsible for the regulation of motor activity and the presence / absence of tremor:

The main function of the bluish spot is to determine what attention will be paid to: external stimuli or internal sensations [9]. In addition, it plays an important role in the processes of cognition and mood control. And if we recall that depression is characterized by a decrease in cognitive and mental abilities, deterioration in the ability to arbitrary concentration of attention, and also, in fact, an inadequate mood [8], then it becomes clear why the bluish spot is important in the etiology and treatment of depression.

Each noradrenergic neuron has receptors (with something, it must receive signals from its fellows and control its own release of the neurotransmitter). These receptors can be divided, firstly, into pre- and postsynaptic (depending on location), and, secondly, into alpha and beta subtypes, which are then divided into mediated effects, localization, as well as affinity to various substances on α1-, α2-, β1-, β2, β3-adrenoreceptors [9].

What is important for us here is that postsynaptic α1, α2, β1 receptors are the main channels for signal transmission, and presynaptic α2 receptors provide negative feedback: when there is too much norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft, it binds to these receptors, and the neuron ceases to release this neurotransmitter [12]. Accordingly (and this is important for treatment), if we block this receptor with an antagonist, then we will “break the brake” in this way, and the amount of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft will increase. The work of some antidepressants is based on this principle, but more on that later.

Having dealt with a little noradrenergic transmission, we turn to the consideration of serotonergic . As the name implies, it is related to neurons that use serotonin as a messenger. Such neurons have their receptors, which can also be divided into pre- and postsynaptic. The first are 5HT1A and 5HT1D. The latter, respectively, 5HT1A (the same type of receptor can be both pre- and postsynaptic), 5HT1D, 5HT2A ( hi, psychonauts! ), 5HT2C, 5HT3, and 5HT4 [9].

Presynaptic receptors, as in the case of noradrenergic neurons described above, perform the function of providing negative feedback : when serotonin in the synaptic cleft becomes abundant, its molecule binds to the presynaptic receptor and the neuron stops its secretions and, accordingly, impulse transmission.

Presynaptic receptors 5HT1D and 5HT1A in this context are distinguished by the fact that the first inhibits the release of serotonin, and the second stops altogether. This is interesting to us in the context that substances that are antagonists of the 5HT1D receptor can enhance serotonergic transmission.

Further - wonder and wonder. The serotonergic neuron has not only serotonergic, but also noradrinergic receptors as presynaptic [9]. This means that the concentration of norepinephrine affects the release of serotonin . As in the case of noradrinergic neurons, we are talking about α2-receptors. This means that the medicine that blocks these receptors (their antagonist) will increase not only the noradrenergic, but also the serotonergic transmission. So works, for example, mirtazapin .

But that's not all. On the body surface of the serotonergic neuron are α1 receptors (also noradrenergic), which work not as a “brake”, but as an “accelerator pedal”, providing a positive feedback link: connecting to such a receptor, the norepinephrine molecule (or any other agonist) enhances neuron release serotonin and, accordingly, the transfer of impulse [12].

Serotonergic neurons are grouped in the brainstem: in the pons and suture nuclei. The projections of these neurons into the cortex affect mood (that is, they are directly related to the affective disorders considered here) [9]:

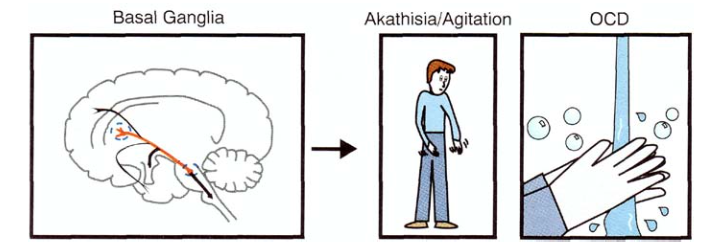

Projections into the basal nuclei affect movements, as well as obsessions and compulsions (this is why antidepressants of the SSRI group are used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder [13]).

Projections to the limbic system are associated with anxiety and panic (5HT2A and 5HT2C receptors play a special role in this),

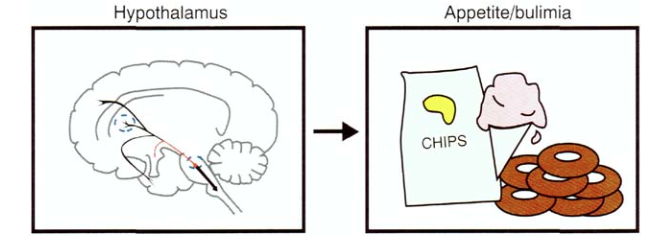

and projections to the hypothalamus - with regulation of appetite and eating behavior (SSRIs are also used to treat bulimia due to the effect on the 5HT3 receptors):

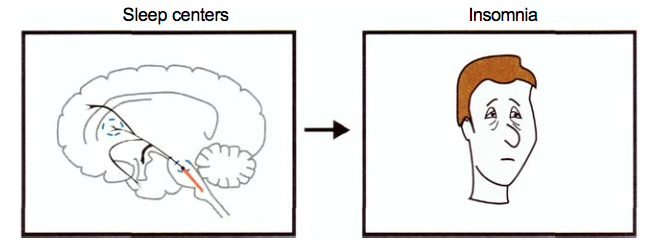

Projections to the diencephalon are responsible for insomnia (which is often the case with depression), and again the main role here is played by the 5HT2A receptors:

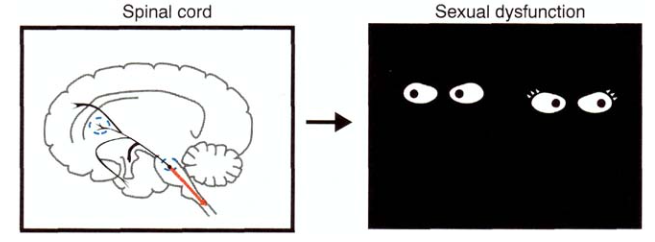

And finally, about sad things: projections to the spinal cord are responsible for the occurrence of erectile dysfunction (a frequent side effect from taking SSRIs, along with a decrease in libido):

So, summing up all of the above, we can conclude that a serotonin deficiency will lead to depression, anxiety, panic phenomena, can provoke phobias, obsessions, compulsions, and even cause gluttony.

And finally, dopamine . The role of dopamine and the dopaminergic pathways was discussed in detail in the previous part of the article; here we briefly limit ourselves to describing the role of this neurotransmitter and the corresponding neurons in the etiology and treatment of depression.

To begin with, the association of depression with the presence of a deficiency of dopaminergic transmission has now been established, and also that agonists (or partial agonists) of dopamine receptors may be useful for treating depressive states [1]. There is evidence that depression increases the density of D2 receptors [2], which also indicates that their agonists or dopamine reuptake inhibitors may be useful for depression. In addition, drugs that increase the level of dopaminergic transmission, help with apathy and lack of energy [3], as well as with abulia, which is also characteristic of some depressed patients.

In general, the breakdown of neurotransmitters by emotion can be represented as such a picture [3]:

And the drugs used to treat it, respectively, in the form of this [3]:

It should be noted here that the monoamine hypothesis is now considered somewhat “naive”, and in fact everything is much more complicated there — there are complex processes for regulating the density of receptors and the mechanisms of gene expression, but this is all beyond the scope of our article. To understand the basics of the functioning of antidepressants at the conceptual level of the monoamine hypothesis is quite enough.

Depression Medications

MAO inhibitors

Historically, these are the first antidepressants [7]. Before talking in detail about them, it is necessary to tell in two words about what MAO itself is .

So, neurotransmitters are synthesized in the neuron, as described in the previous part of the article. However, in parallel with the process of synthesis of these same catecholamines, the reverse process also occurs - their destruction.

In this process, the key role is played by the enzyme monoamine oxidase (also known as MAO), which, in fact, destroys serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine (and much more) [14]. You can visualize it like this:

So, the idea is to stop this destruction process by inhibiting monoamine oxidase , thereby increasing the number of neurotransmitters and increasing the level of appropriate transmission (MAO inhibitors immediately increase both serotonergic and dopaminergic and noradrenergic transmission, which is why they are so effective, and so they have so many side effects) [9].

Monoamine oxidase is of two types: MAO-A and MAO-B. They are quite similar (the amino acid sequences of these proteins are 70% identical), but differ in their functions: MAO-A breaks down adrenaline, norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, dopamine, and also many phenylethylamine and tryptamine surfactants, while MAO-B "works With phenylethylamine and dopamine [15].

Accordingly, by varying the type of monoamine oxidase that will be inhibited, it is possible to influence the amount of which neurotransmitters will increase.

Like many other inventions, the first antidepressant from the group of MAO inhibitors was “discovered” by accident [16]: initially they were going to make a drug for treating tuberculosis (iproniazide), but soon after it began to be prescribed to patients, it became noticeable that their mood changed : for some, it simply improved, while others developed disinhibition and even antisocial behavior [9].

Such an effect on mood quickly attracted the attention of psychiatrists who decided to try to give it to depressed patients and noticed a significant improvement in their condition.

Currently, iproniazid is not used due to high toxicity and a large number of side effects, new, more modern and sophisticated medicines have replaced it. According to their pharmacological properties, they are divided into reversible and irreversible , selective and non-selective .

Reversible MAO inhibitors (IMAO) bind to MAO and form relatively stable chemical complexes that decompose over time, after which the enzyme regains its ability to perform its function. Irreversible bind to it very strongly and deprive the MAO molecule of the ability to split the relevant substances forever (until new molecules are synthesized, which did not have time to contact the irreversible MAOI) [9].

Selective MAOIs are associated with some specific type of MAO (MAO-A or MAO-B), non-selective, respectively, are associated with all types.

Accordingly, choosing the right type of MAOI, a psychiatrist can achieve the desired effect on the patient.

However, it should be noted that today this class of antidepressants is used relatively rarely because of the high risk of side effects caused by a fairly wide range of pharmacological changes caused by these drugs [7,9].

Therefore, when there is an opportunity, doctors prefer to use more focused drugs: tricyclic antidepressants, selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors and other drugs.

The typical MAOI used today can be attributed to moclobemide, pyrazidol, inkan.

Tricyclic antidepressants

This class of drugs got its name not because of the pharmacological effect, but because of the chemical structure of the molecules, each of which has three rings (see the picture above).

On the pharmacological action of tricyclics can be quite different from each other, but they all inhibit the reuptake of monoamines : which more and which to a lesser extent - depends on the specific drug [9].

Tricyclic antidepressants were first synthesized at about the same time as the MAO and were also not designed as antidepressants initially: they tried to make an antipsychotic, got imipramine (the first tricyclic antidepressant), got disappointed in it as a neuroleptic, and then discovered the antidepressant activity of this substance: The schizophrenics who were given it did not show a reduction in the symptoms of schizophrenia itself, but showed an improvement in the symptoms of depression, which is often comorbid [9,16].

As mentioned above, tricyclics block the reuptake of neurotransmitters, which accounts for their therapeutic effect. However, this is not all: in addition to the blocking of reuptake, all tricyclics produce at least one of the following effects: they block muscarinic cholinergic receptors, block H1 hisistomine receptors and block α1-adrenergic receptors. This aspect of the work of tricyclics determines their characteristic side effects — hypotension, nausea, dry mouth, blurred vision, difficulty urinating, dizziness, and memory problems.

Typical representatives: imipramine, amitriptyline, clomipramine.

Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors

An even more modern and “advanced” class of drugs are selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors . They are called selective because, unlike tricyclics that block the reuptake of all major neurotransmitters, these drugs affect the reuptake process of one or two of them.

The most famous drug in this group is fluoxetine (Prozac), which belongs to a subclass of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

One of the most promising modern antidepressants is venlafaxine, which is interesting for its pharmacological profile [17]: depending on the dosage, it can act as a selective reuptake inhibitor: 1. serotonin; 2. serotonin and norepinephrine; 3. serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. In the latter case, its action is similar to the work of tricyclics, however, without the characteristic for the latter side.

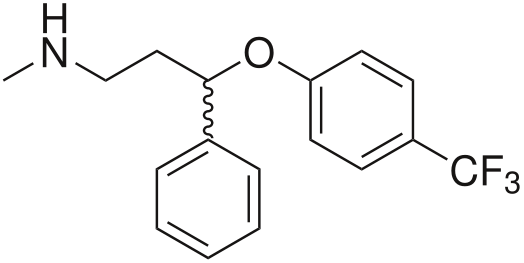

Another interesting and unique drug in terms of its pharmacological effect is bupropion [18]: its trick is that, unlike most antidepressants in this group, which affect the reuptake of serotonin (sometimes serotonin and noradrenaline), bupropion acts on dopamine transporters and norepinephrine. This allows it to be used to treat severe cases of apathetic depression. But at the same time makes it almost useless in the fight against anhedonia.

And he is an antagonist of nicotinic receptors [19], therefore, it is used as a means to combat tobacco smoking.

An interesting fact is that some SSRIs are used not only to treat depression, but also for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder [13], various anxiety disorders, and even bulimia [20,21] (see the section on serotonin and its effects on the body ).

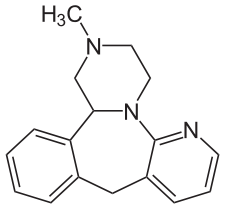

Tetracyclic antidepressants

Like tricyclics, these drugs got their name not because of their pharmacological properties, but because of their structure. However, this is where the similarity between tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants ends - the mechanisms of their work are fundamentally different [9].

If the therapeutic effect of tricyclics is mainly based on the inhibition of the reuptake of monoamines, then here is only a secondary factor. The main thing is the blocking of "inhibitory" presynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors with simultaneous blocking of postsynaptic serotonin 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors [7].

The first effect is an increase in serotonin and norepinephrine in the synapses (remember, we said that α2-adrenoreceptors provide negative feedback and work as a "brake mechanism"?); the second is the reduction of unpleasant side effects of "serotonin": sexual disorders, insomnia and anxiety, nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, anorexia.

A typical representative of this group is mirtazapin (“Remeron”), the structural formula of which is shown in the picture above.

Antipsychotics for augmentation

We talked about antipsychotics in some detail in the previous section, but here it is worth mentioning that some atypics [22,23] (for example, amisulpride) are successfully used for treating depression - in monotherapy or in combination with antidepressants.

The mechanism of action is simple: an antipsychotic blocking presynaptic dopamine D2 and D3 autoreceptors (i.e., negative feedback receptors), thereby potentiating the increase in dopamine release into the synaptic cleft.

Nsi-189

The latest antidepressant, not yet released to the market. It has a very interesting mechanism of action: it does not inhibit reuptake, does not block receptors, but triggers the mechanisms of neurogeneration in the hippocampus [24] - an area of the limbic system that responds including. for the formation of emotions, the consolidation of memory and the generation of theta rhythms while maintaining attention: The

specific mechanism of the antidepressant effect of this drug is not yet known, but it exists.

Personal experience

As always, I want to finish the post by describing an unverifiable and obviously non-indicative personal experience of taking antidepressants.

There will be no references to sources, purely subjective experience.

, . . («»), ( , , ).

(«») . . At all. , , , , .

, , , . , : . , , , , , .

, , , , . . -, , .

: , , , , , . « » ( , , ), ( - ) , — , . , 120 ., .

— , . , . , .

, : , , ( ), . , , , .

(). , , , , , ! , , — , ! , []. — ( , , ) , , .

. , , , , .

, , , .

(«») . . At all. , , , , .

, , , . , : . , , , , , .

, , , , . . -, , .

: , , , , , . « » ( , , ), ( - ) , — , . , 120 ., .

— , . , . , .

, : , , ( ), . , , , .

(). , , , , , ! , , — , ! , []. — ( , , ) , , .

. , , , , .

, , , .

Literature

1. Paul Willner, Dopamine and depression: A review of recent evidence. I. Empirical studies, Brain Research Reviews, Volume 6, Issue 3, December 1983, Pages 211-224, ISSN 0165-0173, doi.org/10.1016/0165-0173 (83) 90005-X.

2. Hugo A. D'haenen, Axel Bossuyt, Dopamine D2 receptors in depression, computed tomography, Biological Psychiatry, Volume 35, Issue 2, January 15, 1994, Pages 128-132, ISSN 0006-3223, doi. org / 10.1016 / 0006-3223 (94) 91202-5.

3. Nutt DJ. Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 69 Suppl E1 4-7. PMID: 18494537.

4. 4. Basics of evidence-based medicine. A manual for the system of postgraduate and additional professional education of doctors. / Under the general editorship of Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Professor RG Oganov .– M .: Siliceya-Polygraph, 2010. - 136 p.

5. ICD-10. Translating to Russian language.

base.garant.ru/4100000

6. 6. N. McWilliams. Psychoanalytic Diagnosis: Understanding Personality Structure in Clin. process: [studies. manual on the specialty "Psychotherapy and honey. psychology"];

7. Satsberg A.F. Guide to Clinical Psychopharmacology / Alan F. Schatzberg, Jonathan O. Cole, Charles DeBattista; per.from English; under total ed. Acad.RAMS A.B.Smulevich, prof. S.V.Ivanova. - 2nd ed. - M .: MEDpress-inform, 2014. - 608 pp., Ill. ISBN 978-5-00030-101-2

8. Bobrov A.S. Endogenous depression. - Irkutsk: RIO GIUVA, 2001. - 384 p.

9. Stahl, SM Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical application / Stephen M. Stahl; with illustrations by Nancy Muntner. — 2nd ed. p .; cm. ISBN 0-521-64154-3 (hardback) —ISBN 0-521-64615-4 (pbk.)

10. A. Beck, A. Rush, B. Sho, G. Emery. Cognitive depression therapy. Peter Publishing House, 2003. ISBN: 5-318-00689-2, 0-89862-919-5

11. BRAIN ANATOMY LECTURE 4. MEDIUM BRAIN (mesencephalon) - Brain Anatomy - Medical Library.

www.nedug.ru/library/anatomy_ of the head_brain / ANATOMY- OF THE BODY-BRAIN- LECTION- MEDIUM#.WRQpVVJeOu5

12. F. Huho. Neurochemistry. Basics and principles. M .: Mir, 1990. ISBN 5-003-001030-0

13. Cochrane evidence. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

www.cochrane.org/CD001765/DEPRESSN_selective-serotonin-re-uptake-inhibitors-ssris-versus-placebo-for-obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd

14. Berry MD, Juorio AV, Paterson IA The functional role of monoamine oxidases A and B in the mammalian central nervous system. (Eng.) // Progress in neurobiology. - 1994. - Vol.42, no. 3 ... PMID 8058968

15. Tipton KF, Boyce S, O'Sullivan J, Davey GP, Healy J (August 2004). "Monoamine oxidases: certainties and uncertainties". Current Medicinal Chemistry .: 1965–82. doi: 10.2174 / 0929867043364810. PMID 15279561

16. Robert A. Maxwell; Shohreh B. Eckhardt (1990). Drug discovery. Humana Press. ISBN 0-89603-180-2. ISBN 9780896031807

17. Redrobe JP, Bourin M, Colombel MC, Baker GB (July 1998). “Dose-dependent properties of the antidepressant activity”. Psychopharmacology. 138 (1): 1–8. doi: 10.1007 / s002130050638. PMID 9694520.

18. Stahl SM, Pradko JF, Haight BR, Modell JG, Rockett CB, Learned-Coughlin S. A Review of the Neuropharmacology of Bupropion, a Dual Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004; 6 (4): 159-166.

19. Slemmer JE, Martin RM, Damaj MI (2000). "Bupropion is a Nicotinic Antagonist". J Pharmacol Exp Ther 295 (1): 321–327. PMID 10991997

20. Cochrane evidence. Antidepressants compared with placebo for bulimia nervosa.

www.cochrane.org/CD003391/DEPRESSN_antidepressants-compared-with-placebo-for-bulimia-nervosa

21. Long-term fluoxetine treatment of bulimia nervosa. Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Research Group. DJ Goldstein, MG Wilson, VL Thompson, JH Potvin, AH Rampey. The British Journal of Psychiatry May 1995, 166 (5) 660-666; DOI: 10.1192 / bjp.166.5.660

22. Noble, S; Benfield, P (December 1999). Amisulpride: A Review of its Clinical Potential in Dysthymia. CNS Drugs. 12 (6): 471–483. doi: 10.2165 / 00023210-199912060-00005

23. Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, Kissling W, Leucht S. Second-generation antipsychotics for depressive disorder and dysthymia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 12. Art. No .: CD008121. DOI: 10.1002 / 14651858.CD008121.pub2.

24. Roger S. McIntyre, Karl Johe, Carola Rong & Yena Lee. The neurogenic compound, NSI-189 phosphate: a novel multi-domain treatment capable of pro-cognitive and anti-depressant effects. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. Published online: 08 May 2017

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/370455/

All Articles