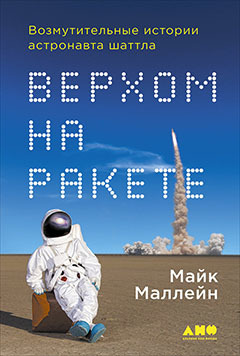

The Russian translation of the memoirs of astronaut Mike Mullein

I lay naked on my side on a table in the bathroom of the NASA Flight Medicine Clinic and put the enema tip in my anus. “This is how the astronaut selection process begins,” I thought. It was October 25, 1977. I was one of about 20 men and women undergoing a three-day program of medical examinations and personal interviews in the process of selecting candidates for astronauts. Almost a year before, NASA announced that it was starting to accept applications from those who wanted to get into the first group of astronauts for flights on shuttles. 8000 people responded. The agency has reduced this entire pile of resumes to about two hundred, and I somehow surprisingly made it into their number. In the following weeks, all of us, each of the 200, had to be on this gurney and provide our own "lower floor" for testing - we were preparing for the study of the intestine.

I lay naked on my side on a table in the bathroom of the NASA Flight Medicine Clinic and put the enema tip in my anus. “This is how the astronaut selection process begins,” I thought. It was October 25, 1977. I was one of about 20 men and women undergoing a three-day program of medical examinations and personal interviews in the process of selecting candidates for astronauts. Almost a year before, NASA announced that it was starting to accept applications from those who wanted to get into the first group of astronauts for flights on shuttles. 8000 people responded. The agency has reduced this entire pile of resumes to about two hundred, and I somehow surprisingly made it into their number. In the following weeks, all of us, each of the 200, had to be on this gurney and provide our own "lower floor" for testing - we were preparing for the study of the intestine.Memoirs of astronaut Mike Mullein occupy the first line in my ranking of English-language memoirs, and I am very glad that their Russian translation has finally been released.

Brief biographical note

Mike Mullein, official NASA photo

Richard Michael "Mike" Mullane was born on September 10, 1945. And when the first Soviet satellite flew over the USA, it became one of tens of thousands of those whom space called. Because of the astigmatism, Mike could not be a pilot, and therefore was not suitable for the first astronaut selection. Nevertheless, he was still able to become a military pilot, but flew an armament operator and did not fly the plane. Fortunately for him, NASA began to make a shuttle, in the crew of which there was a place not only for pilots. Mullein became one of the 35 lucky ones selected from 8,000 applicants to the 1978 set, and worked at NASA for 12 years, making three flights - STS-41D, STS-27 and STS-36. After leaving NASA, he became an orator-motivator and, on the material of NASA disasters and his aviation experience, agitates for safety at work. The book "Riding a Rocket: Outrageous Stories of the Space Shuttle Astronaut" was published in 2006.

')

Memoirs

I strongly advise reading the first pages of the translation available on the publisher’s website, because they perfectly show the general mood and style of the book. Mullein manages to combine the maximum frankness in some unpleasant places, and in some places to the obscenity of funny stories with the technical details of aviation and space technology, and complements this with the shrill romance of travel and flight with unique sections of American society and NASA. The result is a bright vinaigrette, where on one page you restrain indignation or even gagging, the next one snorts with laughter, then you sympathize with people in a difficult situation, or even brush away the dead, and the new page opens in all its cosmic bottomlessness. Mullein also does not feel sorry for himself, talking about what many would prefer to keep silent. And, of course, the technical description of the Space Shuttle is very well described in the book.

Transfer

The book has a lot of aviation and space terms. The translator had to have a technical base (I have seen non-amateur translations of cosmic literature with unimaginable blunders). Therefore, it is very good that Igor Lisov, the editor of the journal Astronautics News, acted as the translator of the book. Further, the English version is not so easy to read, because the book contains quite a lot of the realities of American culture without explanation. For us Russians, it is not clear who Cheryl Tiggs, Christie Brinkley or Bo Derek are. Therefore, there are a lot of notes in the book - 108 at the end of the book and 205 sub-page notes, which should greatly facilitate perception.

I do not know whether the publisher podgadvat specially, but the proximity of the Day of Astronautics, in my opinion, makes familiarity with this book very timely.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/370349/

All Articles