Ask Ethan: the multiverse and the roads we haven't gone

The word “multiverse” is used by many people, but not all mean by it the same concept. Reader Chris Olson asks about two different meanings of the word:

How are Everett's ideas about quantum mechanics and perpetual inflation related to each other, if they are at all? Is it possible to distinguish between the multiverse that these ideas speak of?

')

There are many options that people can keep in mind by using the term “multiverse” instead of “Universe”, so let's go over them, starting with ideas that require the least new assumptions and ending with the most speculative.

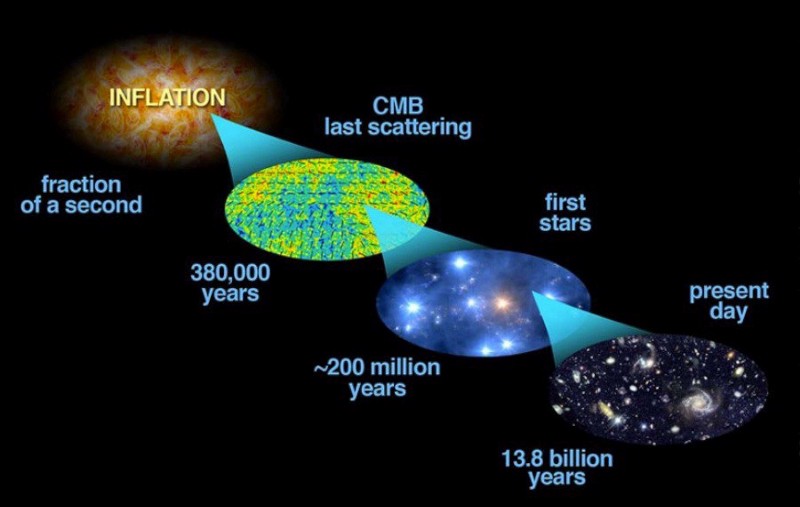

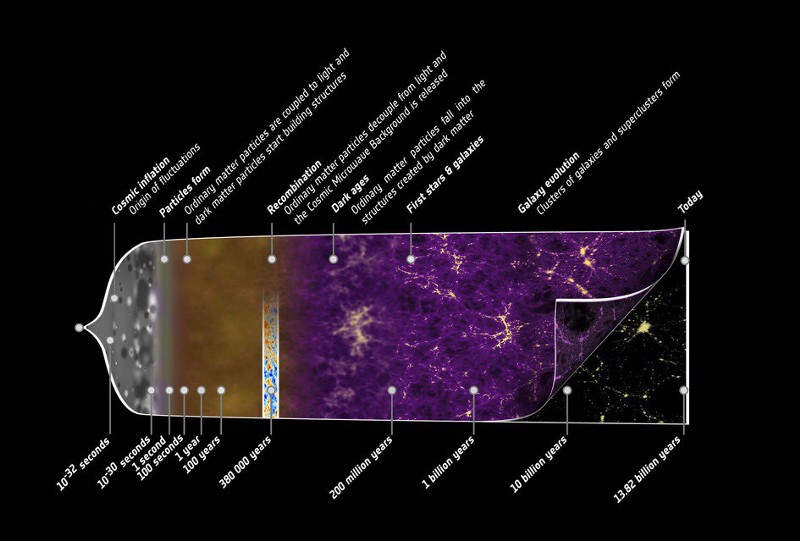

1) Universe beyond our field of vision. Saying “Universe”, we often mean its observable part. Since the Universe known to us began with an event that we know as a hot big bang — when a hot, dense Universe filled with matter and radiation first appeared 13.8 billion years ago and began to expand, cool and gather into lumps under the influence of gravity — we limited to what we can observe. Even the signals that appeared at the same moment, and freely traveling at the speed of light in the constantly expanding Universe, were able to pass only a finite distance since then. In our Universe, where there is normal matter, dark matter, dark energy, neutrinos, radiation and all that we still know, this distance is 46.1 billion light years with its center at the point of our stay.

There is no reason why something else cannot exist outside of this boundary. Just everything that is in the unobservable part of the universe, did not have enough time to reach us. Over time, an increasing part of the Universe will be revealed to us from our point of observation, even taking into account the action of dark energy. But how many things are there? Judging by the observable curvature of space, the entire existing Universe extends at least 250 times longer in all dimensions, that is, its volume is at least 250 3 , or 15 million times more than the observed one. It is possible that it is generally infinite, although it is not known for sure. But this is the most conservative of all versions of the multiverse - just more of the same. But maybe something else.

2) Various "pockets" of the universe in places where inflation ended. The big bang could be the beginning of what we know as the “our” Universe, but we cannot extrapolate back to any stage of the hot and dense state. We only know (due to relic radiation) that the Universe in the hot Big Bang reached temperatures not exceeding 10 30 K. It is a lot, but does not reach the Planck scale, to singularity, or to break the laws of physics known to us. And one of the conclusions is that before the Big Bang there was something else corresponding to what we denote as the initial conditions: cosmic inflation. Inflation is the essence of the life of the Universe before the Big Bang, which prepares it, resulting in one:

• stretches to a flat state

• is exempt from all relic particles created before inflation ended,

• has the same temperature and energy density throughout the volume,

• contains a uniform range of fluctuations.

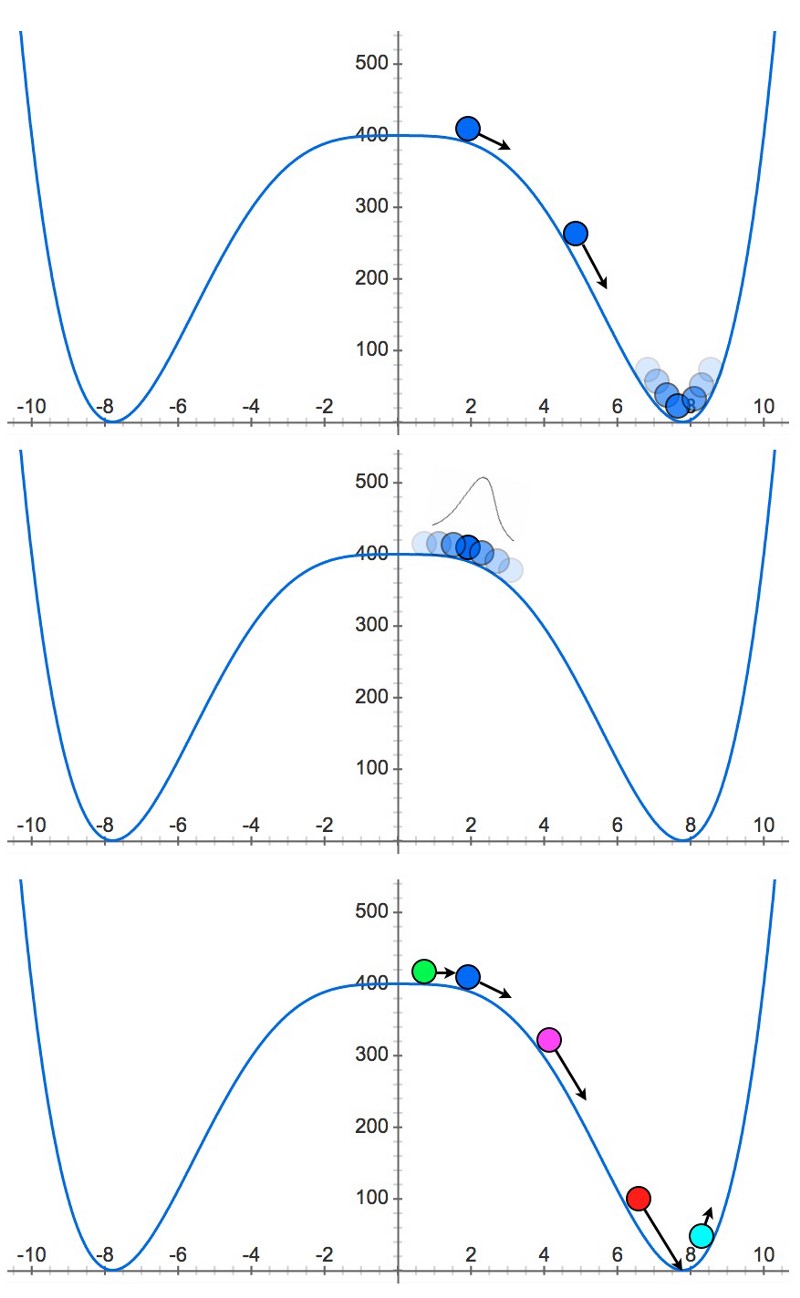

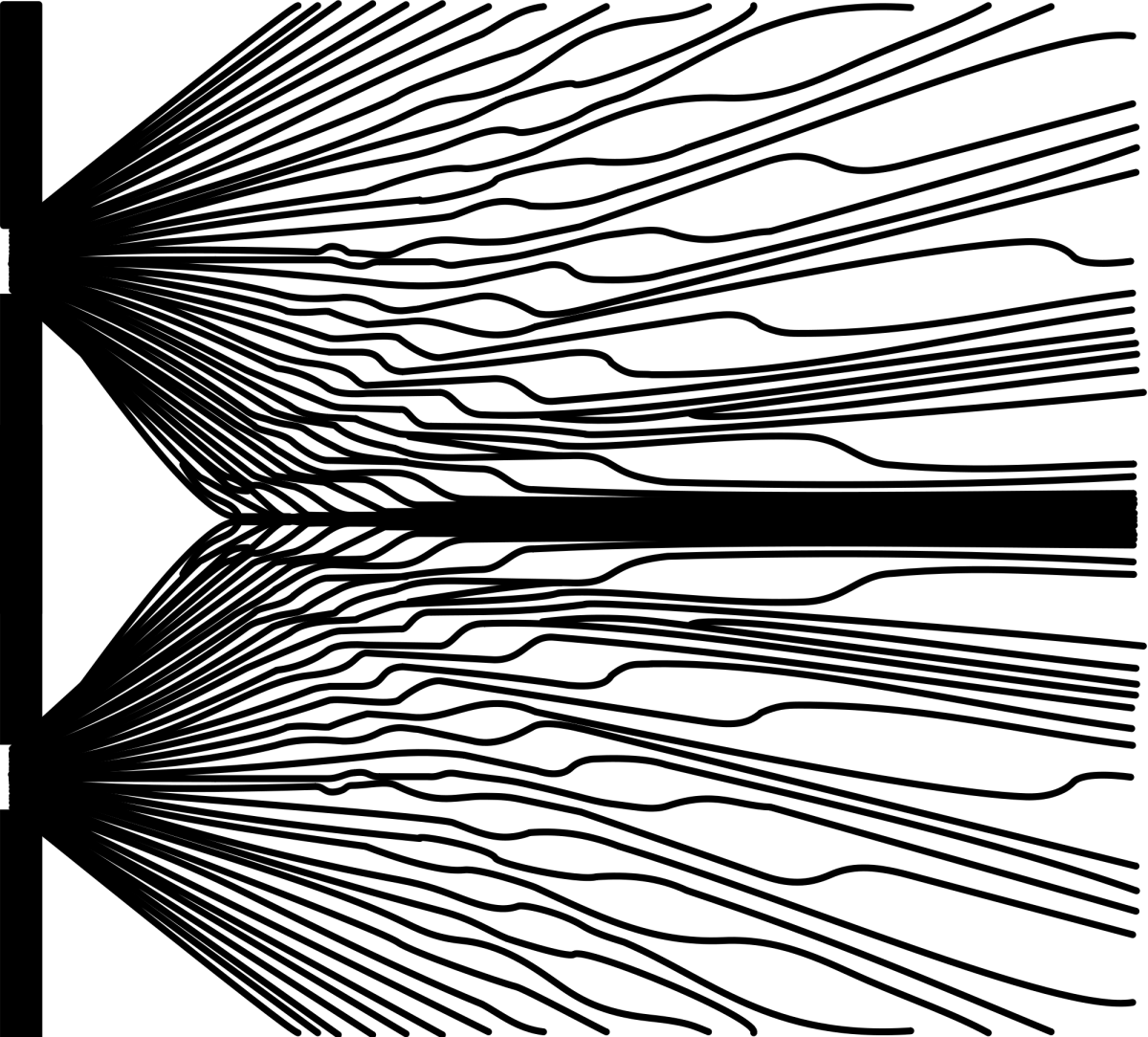

Inflation is like a ball rolling from a hill, only it is a quantum ball, so there are probabilities at every point where it rolls (or does not roll) off the hill.

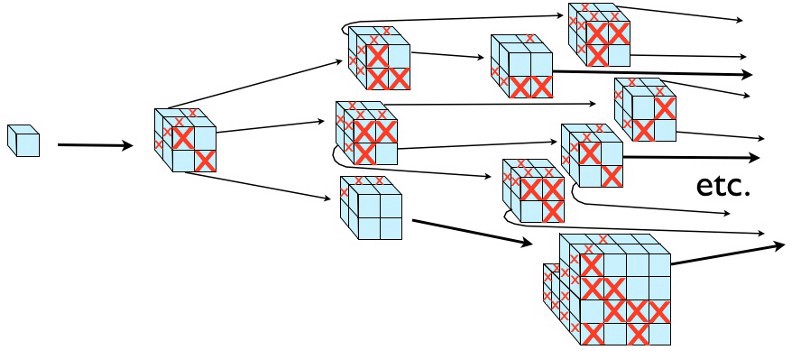

In places where inflation remains at the top of the hill and does not roll, inflation continues, and creates more and more space. Where it slips, inflation stops and hot Big Bang occurs. And although inflation ended in our region of space 13.8 billion years ago, it is unreasonable to believe that it ended everywhere. Some regions of the cosmos will continue to experience inflation forever. And while the rate of expansion of space is greater than the rate at which inflation pockets end, an infinite number of Big Bangs unrelated to each other will occur, and inflation will continue to go where it has not ended, forever.

In the picture, the red crosses mark regions, such as ours, in which inflation has ended. But there are an infinite number of regions where it ends. This Multiverse is even larger than “more of the same Universe” from the previous paragraph. And this is the first of those multiverse that the reader asked about: the multiverse of eternal inflation.

3) Different versions of you in different parts of the multiverse. In the observable part of the Universe, there are 10 90 particles (including photons and neutrinos), and all of them experience interaction and collision with each other. Everyone has a location and impulse, a unique story, and about 10 28 are currently combined to make us together. If we take the expected rate of expansion of space and accept that most of it has expanded at this rate throughout the entire history of the Universe (13.8 billion years), we can calculate how many possible universes exist, similar to ours.

Damn a lot! Realistically, we can talk about 10 10 50 universes, starting with initial conditions similar to ours. And this is 10 1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 Universes - perhaps the largest number of all that you tried to imagine. But the numbers describing the number of possible variants of particle interactions are even greater. After all, to get an identical twin to you, the whole history of the Universe had to develop exactly as ours developed, until you made decisions about:

• devices for the job,

• buying one at home

• a kiss you liked the person

or for some other reason.

In our Universe in bulk particles, 10 90 . With each interaction of two of them, there is not a single scenario, but a whole quantum spectrum. No matter how sad it is, there is much more than (10 90 )! Possible variants of particles, and this number is many times more complex than such a trifle as 10 10 50 . In other words, the number of possible options for the interaction of particles in any Universe tends to infinity faster than the number of possible universes arises due to inflation. Inflation would have to go on forever, until for such a situation our Big Bang would have been possible, and this contradicts the Borda-Guta-Vilenkin theorem , which shows that inflation cannot be extrapolated to infinity to the past. It turns out that this option is unlikely.

4) Quantum entangled twins in different pocket universes. We come to the second part of the reader's question - quantum mechanics Everett. If the 3rd option is real, and there are other versions of you in other pockets of the multiverse, are they confused? Quantum physics can be interpreted differently, that is, it can be approached in different ways, giving the same answers. Quantum systems may have wave functions that propagate in time and instantly collapse during interactions, or it may be a set of all possible scenarios from which only one option is selected. The Hugh Everett Interpretation — a multi-world interpretation of quantum mechanics — postulates that there are an infinite number of parallel universes, and when making a decision we choose one of the many possible paths. So there are universes in which you chose or didn’t choose that job, bought or didn’t buy that house, etc.

And even if there were an infinite number of universes, it would be impossible to create confusion between them, although this does not stop people who like to speculate. This is another one of the untestable features that requires making some unusual assumptions. But we can go even further into this rabbit hole of the multiverse.

5) Different universes with different laws of physics. This is an even more speculative concept, based on the assumption that inflation can end in different ways, leading to the emergence of different laws of physics and fundamental constants that are different from those that are present in our Universe. With this multiverse, some pockets will recollapse, others expand so quickly that stars and galaxies will form there; some will not have dark matter, others will be completely composed of dark matter; in some, the cosmological constant will be more, less, or even negative. There may even be universes with completely different particles and interactions between them. This is also not to check.

The truth of the first variant follows from our observations: the Universe is larger than what we can observe. Based on the information about inflation, we are almost certain that version 2 is correct: there are regions of space outside our Universe, where inflation ended at different times, and each had its own hot Big Bang, as well as regions with still ongoing inflation, as well as in which it will last forever. Our notions of infinity say that option number 3 is most likely impossible, and therefore number 4 falls out. The 5th option is funny, but for it there is neither evidence nor ability to check, and the fact that inflation ends long before the Planck scale is reached gives us serious reasons to doubt its possibility. The multiverse is no doubt real, but it all depends on which version of the multiverse you are sticking to.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/370177/

All Articles