Can nature be unnatural?

Decades of perplexing experiments make physicists consider an amazing possibility: it is likely that the universe does not make sense

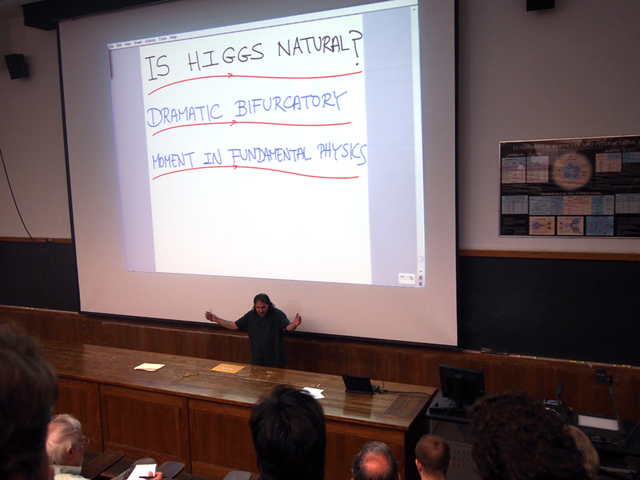

On a cloudy day in late April, physics teachers and their students crowded into a wood-paneled auditorium at Columbia University to listen to a talk by Nim Arcani-Hamed, a prominent theoretical physicist who worked at the Institute for Advanced Studies in nearby Princeton. Arkani-Hamed, with long, shoulder-length hairs behind his ears, showed ambivalent, and at first glance, contradictory conclusions from the results of recent experiments conducted at the Large Hadron Collider.

“The universe is inevitable,” he announced. “The universe is impossible.”

')

The impressive discovery of the Higgs boson in July 2012 confirmed the nearly 50-year theory of how elementary particles get mass, which allows them to form structures such as galaxies or people. “The fact that they found him approximately where they expected was the triumph of the experiment, the triumph of the theory and a sign of the efficiency of physics,” said Arcani-Hamed to the crowd.

However, in order for the mass, or equivalent energy, of the Higgs boson to have a physical meaning, a whole cloud of particles had to be discovered. But none of them was ever found.

Having discovered only one particle, the experiment at the LHC deepened the already deep problem of physics that had been brewing for several decades. Modern equations with stunning accuracy reflect reality and correctly predict the values of many natural constants and the existence of particles like the Higgs boson. But a few constants — including the Higgs boson mass — differ exponentially from what these proven laws predict, so that no life in the Universe could have arisen, unless there is an unimaginable number of tweaks and mutually annihilating quantities in it.

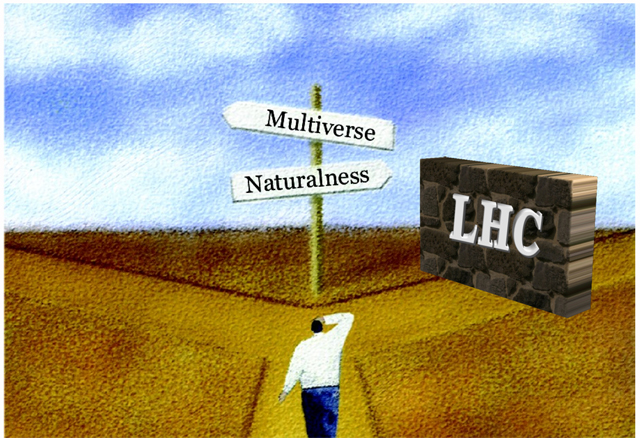

The notion of “naturalness” was threatened, the dream of Albert Einstein that the laws of nature are immaculately beautiful, inevitable and self-sufficient. Without it, it turns out that these laws are simply an arbitrary and disorderly result of random fluctuations of the fabric of space-time.

The BAC began to push protons again in 2015 in search of answers. But in the papers and interviews, Arkani-Hamed and other outstanding physicists already face the possibility that the Universe may be unnatural. At the same time, there are heated debates about what needs to be done to prove this.

“10-20 years ago, I firmly believed in naturalness,” says Nathan Seiberg, a theoretical physicist at the Institute, in which Einstein himself taught from 1933 to 1955, before the year of his death. “Now I’m not sure about that. I hope that we have not yet taken into account something, another mechanism explaining all these things. I don't know what it could be. ”

Physicists say that if the universe is unnatural, and the values of all the constants that make life possible are extremely unlikely, then there must be a huge number of universes in which other options are realized. Otherwise, why are we so lucky? Unnaturalness could give a big boost to the multiverse hypothesis, in which our Universe is just one bubble in an endless inaccessible froth. According to a popular but controversial platform called “string theory,” the number of possible types of universes that can occur in the multiverse tends to 10,500 . In some of them, random coincidences may lead to the appearance of strange constants that we observe.

In such a picture, not everything that is connected with the universe is inevitable, which means that something is unpredictable. Edward Whitten, an expert on string theory at the Institute, replied by mail: “I would be happy if the multiverse theory were not confirmed, partly because it limits our ability to understand the laws of physics. But when creating the universe, no one of us was consulted. ”

“Some people simply hate her,” says Raphael Bousso, a physicist at the University of California at Berkeley, who helped develop the multiverse scenario. “I do not think that we can analyze on emotions. This is a logical possibility, to which, in the absence of naturalness, in the LHC more and more are inclined. ”

What else will be opened or not opened at the LHC, will support one of two possibilities: either we live in an overly complex, but unique, Universe, or we live in an atypical multiverse bubble. “In 5-10 years we will be much smarter thanks to the LHC,” says Seiberg. "It's so cool. You only need to lend a hand. ”

Cosmic coincidence

Einstein wrote that for a scientist "religious feeling takes the form of enthusiastic amazement at the harmony of natural laws," and that "this feeling is the guiding principle of its work and life." Indeed, in the 20th century, a deeply rooted belief in the harmony of the laws of nature - in “naturalness” - proved to be a reliable guide in the search for truth.

“There are a lot of discoveries in the account of naturalness,” Arcani Hamed said in an interview. In practice, it is required that physical constants (particle masses and other fixed properties of the Universe) arise directly from the laws of physics, and not from unlikely abbreviations. Every time a constant looks like a fine adjustment, as if its original value was magically set to change other effects, physicists suspected that they were missing something. They searched for and found a certain particle or property responsible for the value of a constant, which eliminated the need for precise adjustments.

But now the self-healing properties of the universe are failing us. The Higgs boson has a mass of 126 GeV, but interactions with other known particles should add about 10,000,000,000,000,000 GeV to its mass. This means that the “bare mass” of the boson, or its starting value, must be a negative value of such an astronomical quantity, and it is almost perfect to nullify it, leaving only a small part of its mass: 126 GeV.

Physicists have already used three generations of particle accelerators in search of new particles, predicted by the theory of supersymmetry, which should reduce the mass of the Higgs boson by exactly as much as known particles increase it. But so far they have not found anything.

Even if the updated LHC finds new particles, they will definitely be too heavy to affect the Higgs mass in a proper way. Higgs will still be 10-100 times easier than necessary. Physicists argue whether it is acceptable for a natural and unique universe. “A little tweaking - maybe it just happens,” says Lisa Randal, a professor at Harvard University. But according to Arkani-Hamed, “a little tweaked is like being a little pregnant. This does not happen.

If new particles do not appear, and Higgs will remain astronomically fine-tuned, then the multiverse hypothesis is in the spotlight. “This does not mean that it is correct,” says Busso, a longtime supporter of the multiverse idea, “this means that there are no more options.”

Alessandro Strumia (right) and David Curtin discuss the idea of “modified naturalness” at the 2013 Brookhaven Forum

Some physicists, such as Joe Likken of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, and Alessandro Strumia of the University of Pisa in Italy, see the third option. They say that physicists do not correctly measure the effects of other particles on the Higgs mass, and that with other methods of calculation, the mass looks natural. This “modified naturalness” breaks down if additional particles are included in the calculations, for example, dark matter - but a similar non-standard way can generate other ideas. “I am not agitating for the idea, I just want to discuss its consequences,” Strumia said during a report at the Brookhaven National Laboratory.

But modified naturalness does not solve the larger problem existing in physics: that space did not annihilate due to its energy immediately after the Big Bang.

Dark energy

The energy inherent in vacuum (known as vacuum energy, dark energy or cosmological constant) in an incomprehensible amount, trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion less than the calculated natural, although self-destructing, value. While there is no theory that could fix this huge discrepancy. It is clear that the cosmological constant must be extremely heavily adjusted in order for life to have a chance.

The idea of a multiverse that explains such absurd luck has gained popularity among cosmologists over the past few decades. She increased credibility in 1987, when Nobel laureate Stephen Weinberg, now teaching at the University of Texas at Austin, calculated that the cosmological constant also occurs in the multiverse scenario. Of all the possible universes capable of supporting life - and only they can be observed and observed - in ours is the least accurate tweaks. “If the cosmological constant were significantly greater than the observed value, for example, once in 10, then we would not have galaxies,” explains Alexander Vilenkin, a cosmologist and theorist studying the multiverse theory at Tufts University. “It’s hard to imagine how life could exist in such a universe.”

Most particle physicists hoped that more verifiable explanations would be found for the problem of the cosmological constant. But they did not find anything. Now, the Higgs unnaturalness makes the cosmological constant unnaturalness more significant. Arkani-Hamed believes that these problems may be related. “We do not understand the basic and most surprising fact concerning our universe,” he says. “She is big and there are a lot of big things in her.”

The multiverse became more than just an argument in 2000, when Bousso and Joe Polchinsky, a professor of theoretical physics at the University of California at Santa Barbara, discovered a mechanism capable of generating a whole panorama of parallel universes. String theory, a hypothetical "theory of everything" that considers particles as tiny vibrating lines, postulates the existence of 10 dimensions of space-time. On a human scale, there are only three dimensions of space and one time, but string theory experts say that six additional dimensions are closely connected at any point in the fabric of our four-dimensional reality. Bousso and Polchinski estimated that there are 10,500 options for linking these dimensions, which leads to a huge number of possible universes. In other words, naturalness is not required. There is no one, unavoidable and ideal universe.

“It was a moment of enlightenment for me,” said Busso. But the work provoked fierce criticism.

"Particle physicists, especially string theory experts, dreamed of predicting all the constants of nature," explains Busso. - Everything would come out of mathematics, pi and twos. And then we came and said: “You know, nothing will happen, and there is a reason for that. We think about it incorrectly. ”

Life in the universe

The Big Bang, in the Busso-Polchinski variant, is a fluctuation. The compact six-dimensional knot, which constitutes one of the stitches of the fabric of reality, suddenly changes, releasing the energy that forms the bubble of space-time. The properties of this universe are determined randomly: through the amount of released energy. A huge number of emerging universes filled with vacuum energy. They either expand, or collapse so quickly that life does not have time to arise in them. But some atypical universes, in which the reduction leads to a small value of the cosmological constant, are similar to ours.

In his work on arXiv.org, Busso and his colleague from Berkeley, Lawrence Hall, argue that in the case of multiverse Higgs mass makes sense. They found that in bubble universes containing a sufficient amount of visible matter (as opposed to dark) for the existence of life, very often there are supersymmetric particles that are beyond the energy available at the LHC, and a precisely tuned Higgs boson. Other physicists also showed in 1997 that if the Higgs boson were five times harder, this would prevent the formation of atoms heavier than hydrogen, which would make the universe lifeless.

Despite the seemingly successful explanation, many physicists are worried that after accepting the multiverse, little will change. The existence of parallel universes cannot be verified, and the unnatural universe is inaccessible to understanding. “Without naturalness, we will lose the motivation to search for new physics,” says Kfir Blum from the Institute of Advanced Studies. "We know that she is there, but there are no convincing arguments for why we should find her." This opinion is very common. “I would prefer the universe to be natural,” says Randal.

But physicists can get used to theories. After spending more than a decade getting used to the multiverse, Arkany-Hamed finds it possible - and a viable theory for understanding how our world works. “It is interesting that practically any of the results obtained at the LHC will direct us along one of these divergent paths,” he says. “And this is a very, very important conclusion.”

Naturalness can win. Or it may be a false hope in a strange but comfortable corner of the multiverse. As Arcani Hamed told his audience in Colombia, “stay with us.”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/370147/

All Articles