Mathematical models help to remove the threat from networks

Gene Stanley always goes down the stairs, holding the railing. For a well-preserved 71-year-old man, he is too afraid to break his thigh. At his age, such a change can turn into critical complications, and Stanley, a professor of physics at Boston University, thinks he knows why.

“It all depends on everything,” he says.

')

In 2010, Stanley and his colleagues discovered the mathematical laws by which he works, as he calls it, “the extreme fragility of the state of interdependence.” In a system of interconnected networks, for example, in the economy, infrastructure of a city or a human body, their model claims that a small failure in one network can spread in a cascade throughout the system, leading to a catastrophe.

The discovery, which was first written in 2010 in the journal Nature , led to the emergence of more than 200 related studies, including an analysis of the national “blackout” in Italy in 2003, a global food price crisis in 2007 and 2008, and a sharp fall in the US securities market on May 6, 2010 .

“In isolated networks, minor damage will not lead to serious consequences,” said Shlomo Havlin, a physicist at the Bar-Ilan University in Israel, co-author of the 2010 paper. “Now we know that a sharp collapse can happen because of the connections between the networks.”

And although scientists recommend carefully applying the results of the work of simplified mathematical models to the real world, some recommendations begin to appear. Based on refinements using new data, new models recommend that interconnected networks use backups, mechanisms to cut ties in a crisis, and tight regulation to delay widespread failure.

“We hope that there is such a golden mean in which you get the benefits of using networks that do not overlap with the risk of their failure,” says Raissa D'Souza, a complex systems theorist at the University of California, Davis.

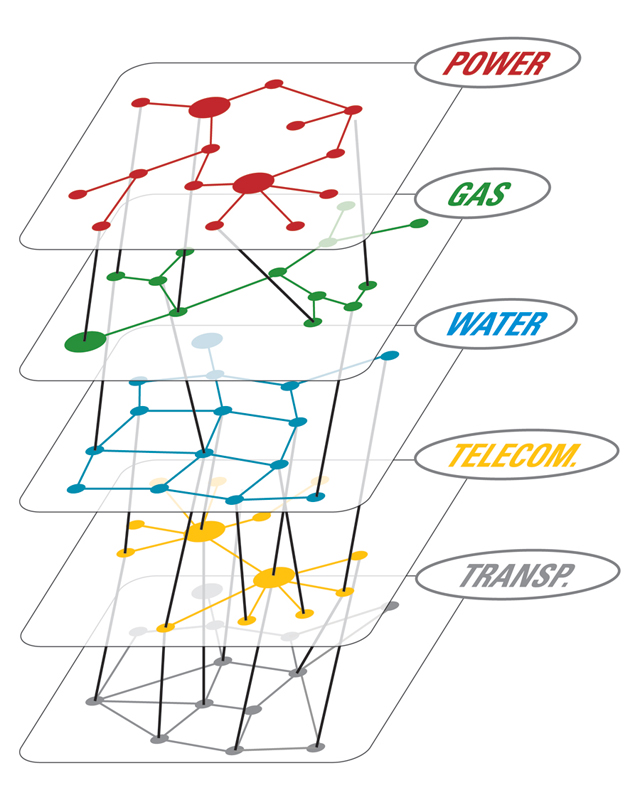

Electricity, gas, water, communications and transportation - these networks are often intertwined with each other. When nodes of one network depend on nodes of another, failure of nodes in some networks can lead to the collapse of the entire system.

To understand the vulnerabilities of a system where the nodes of one network depend on the nodes of another, imagine a “small network”, an infrastructure in which power plants are controlled by a communication network that receives energy from a network of power plants. In the case of an isolated network, the removal of several nodes from any network does not hurt much, since the signals can bypass the failed locations and reach most of the remaining nodes. But in paired networks, fallen nodes automatically cut down the nodes of another network that depend on them, which knock down the nodes that already depend on them, and so on. Scientists model this cascade by counting the size of the largest cluster of connected nodes in each network, and the answer depends on the size of the largest cluster in another network. When clusters are interconnected, reducing the size of one of them triggers a cascade of reducing clusters, working in both directions.

Stanley, Havlin and their colleagues found that when the system reaches a critical level of damage, the failure of just one additional node reduces all clusters to zero size, and kills the entire system interconnection. The critical point depends on the system architecture. In one of the most realistic models of a connected network, the failure of only 8% of nodes in one network — a realistic damage level for a real system — reduces the entire system to a critical level. "The fragility that exists because of this interdependence is scary," says Stanley.

However, in another model recently studied by Desouza and her colleagues, the rare links between individual networks help suppress large-scale cascades, indicating that there are no universal models of networks. To assess the behavior of smart networks, financial markets, transportation systems and other real independent networks, “you need to start with the existing world and its data, and come up with mathematical models that reflect real systems, and not use models because they are beautiful and analytically obedient”, says Desuza.

In several papers in the journal Nature Physics, economists and physicists use groundwork on interconnected networks to determine risk in the financial system. In one study, a group of scientists from different fields, including the Nobel laureate, economist Joseph Stiglitz, discovered the inherent instability of a complex multi-trillion derivatives market and proposed rules that can help stabilize it.

Irena Vodenska, a professor of finance at Boston University, working together with Stanley, created a special model of the paired network according to data from the 2008 crisis. An analysis published in the journal Scientific Reports showed that modeling the financial system as a network of two networks — banks and banking assets, where each bank is associated with assets available to it in 2007 — correctly predicted in 78% of cases which banks should collapse.

“We believe that this model is potentially useful for stress testing financial systems,” said Vodenska, whose research is funded by the European Union's financial crisis prediction program. While globalization is tying financial networks more tightly, she says, regulators must track “sources of contamination” —for example, the concentration of certain assets — before this will lead to an epidemic of failures. To identify such sources, "it is necessary to think in the spirit of networks consisting of networks," she says.

Leonardo Duenas-Osorio, an engineer from Rice University, visited a damaged high-voltage substation in Chile after a major earthquake in 2010 to gather information about the response of the electrical grid to the crisis

Scientists apply similar techniques to assessing infrastructures. Leonardo Duenas-Osorio, an engineer from Rice University, analyzes how vital systems respond to natural disasters. When an earthquake of magnitude 8.8 occurred in 2010 in Chile, most of the networks were restored in just two days. The Duenas-Osorio study shows that such a quick recovery was possible because the power plants were quickly disconnected from the centralized telecommunications system, which usually controlled the distribution of electricity across the network, and fell in some regions. The power plants were manually operated until damage to other parts of the system was repaired.

“After an unusual event, most of the detrimental effects occur in the very first interaction cycles,” says Duenas-Osorio, who also studies New York’s reaction to Hurricane Sandy. “So when something goes wrong, we need the ability to separate networks in order to prevent the effects going forward and back between them.”

Deshuza and Duenas-Osorio are working together to create accurate models of infrastructure systems in Houston, Memphis and other cities to identify weak parts of the systems. “Models help us explore alternative configurations that could be more effective,” explains Duenas-Osorio. And since the interdependence of networks is constantly growing, "we can model increasing integration and see what happens."

Scientists also use models to find out how to fix failed systems. “We are exploring optimal approaches to network recovery,” says Havlin. “When the network crashes, which node should I lift first?”

It is hoped that networks from networks may be unexpectedly fault tolerant for the same reasons that they are vulnerable. As Duenas-Osorio says, “is it possible, using strategic improvements, to cause positive cascades, in which a slight improvement brings about serious advantages?”

These issues attract governments of all countries. In the United States, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which protects state infrastructure against weapons of mass destruction, considers the study of interdependent networks a high priority in the category of basic research. Practical applications of research are emerging, for example, new models of power grids at military bases. But most of the research deals with the analysis of mathematical subtleties of the interaction of networks.

"We have not yet reached the level of 'let's redo the Internet,'" said Robin Burke, an information technology specialist and former director of the Agency’s programs, who managed his work on research on interdependent networks. "Most of the research is still at the level of the foundations of science - the science that we desperately need."

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/370089/

All Articles