On October 4, 1957, the first artificial Earth satellite was launched into orbit.

Hello! We decided to highlight this date in the history of our country and decided to share an excerpt from the book “A Little Book about Big String Theory” by Stephen Gabser.

Chapter 2

Quantum mechanics

Having received a bachelor's degree in physics, I spent a year in Cambridge studying physics and mathematics. Cambridge is a place with green lawns, a leaden sky and centuries-old traditions of high scientific school. I studied at St. John's College, whose history goes back five centuries. I remember that there was a beautiful grand piano standing on one of the upper floors of the first building - the oldest building in Cambridge. Among the things that I performed on it was Chopin's “Impromptu-fantasy”. The main part of this piece contains two rhythmic patterns - 4: 3 polyrhythm. The parts of both hands are played at the same tempo, but for every four notes for the right hand there are three notes for the left, which gives the whole composition an ethereal, flowing sound. This is the beautiful part, and it makes me think about quantum mechanics. In order to explain why, I will first have to tell a little about this remarkable theory, but I am not going to set forth quantum mechanics entirely, but only to speak about those concepts that give me reminiscences with music, such as Chopin's “Impromptu Fantasy”.

In quantum mechanics, any motions are possible, but some are preferable to others. These preferred motions are called quantum states. They have certain frequencies. Frequency is the number of times per second that something is rotated or repeated. In Impromptu Fantasy, the right-hand part has a higher frequency than the left-hand part, and these frequencies are referred to as four to three. That which “rotates” in quantum mechanics is of a more abstract nature. Technically, this is the phase of the wave function. You can think of the wave function as the second hand of a clock, which makes a complete revolution in one minute. The phase of the wave function does the same as the second hand, it rotates, only with a much higher frequency. The speed of this rotation characterizes the energy of the system, which I will discuss in more detail later. Simple quantum systems, such as a hydrogen atom, have frequencies that are in fairly simple relationships with each other. For example, the phase of one quantum state can make nine turns, while the phase of the other is four. This is very similar to the 4: 3 polyrhythm of Shopen's Impromptu Fantasy. But frequencies in quantum mechanics are much higher. For example, the characteristic frequency of a hydrogen atom is of the order of 10 ^ 15 revolutions per second. This is much faster than performing Impromptu Fantasy, where the right hand plays no more than 12 notes per second.

')

The rhythmic charm of "Impromptu fantasy" can hardly be called its main charm - at least not in my performance. Her melody soars over the sad bass, and the notes merge together in chromatic blur. At the same time, harmony slowly shifts, shading the fragmentary fluttering of the main theme. Subtle polyrhythm 4: 3 provides only the background for Chopin's most memorable work. Similarly, quantum mechanics, having a discrete set of oscillating quantum states at its core, is blurred at the macro level into a colorful and complex world accessible to our immediate perception. These quantum frequencies have a very real reflection in our world. For example, the yellow-orange light of a street lamp has a certain frequency associated with the oscillations of electrons in sodium atoms. This frequency determines the orange color of the lantern.

In the remainder of this chapter, I will focus on three aspects of quantum mechanics: the uncertainty principle, the hydrogen atom, and the photons. Along the way, we are confronted with energy in its new quantum-mechanical role, closely related to frequency. The music analogy is very good for explaining the role of frequency in quantum mechanics, but, as we will see in the next section, this theory contains other key ideas for which explanation it is not so easy to find analogies in everyday life.

Uncertainty

The uncertainty principle is one of the cornerstones of quantum mechanics. He argues that the position of a particle and its momentum can never be measured simultaneously. The previous statement is not quite correct, so let me explain more fully. In any measurement of the coordinates, we have some uncertainty of the result, denoted as Δx (pronounced "delta X"). Suppose, measuring a section of fabric with a soft tailor’s meter, you are able to determine its length with an accuracy of no more than 0.5 cm. Then the uncertainty of your measurement will be: Δx ≈ 0.5 cm. This means that the “delta X” is about half a centimeter. A tailor can call his colleague and say: "The gene, the length of the fabric you sent me, is two meters long with an accuracy of half a centimeter." (Of course, I mean the European tailor, because American tailors would operate with feet and inches.) In other words, the tailor believes that the length of the cut fabric is x = 2 m, and the uncertainty of this length: Δx ≈ 0.5 cm.

We are well acquainted with the impulse, but it is better to understand what kind of animal it is, you can, looking through the eyes of a physicist at the collision of two bodies. If two billiard balls collided head-on and completely stopped, then before the collision they had the same impulses. If, after a collision, one ball is still moving in the original direction, but slower, it means that it had more momentum than the second one. Impulse and mass are connected by a simple formula: p = mv. But let's not go into details yet. The bottom line is that impulse is something you can measure, and this measurement has some uncertainty, which we denote as Δp.

The uncertainty principle states that Δp × Δx ≥ h / 4π, where h is a certain constant, called the Planck constant, and π = 3.14159 ... is the well-known ratio between the circumference and its diameter. I prefer to say: “delta pe delta x is greater than or equal to four pi”, but if you prefer “scientific and literary” physical and mathematical language, then you should say: “the product of the impulse uncertainties and the coordinates of the particle are not less than the ratio of Planck's constant to four pi. Now, I hope, it is clear why I said that the statement given at the beginning of this section is not quite correct: you can simultaneously measure the coordinate and momentum of a particle, but the uncertainty of these two dimensions can never be less than the equation Δp × Δx ≥ allows h / 4π.

To better understand how the principle of uncertainty works, imagine that we have trapped a particle that has a size Δx. The position of the particle is now known to us with uncertainty Δx (provided that the particle is inside the trap). The uncertainty principle states that we cannot find out the magnitude of the momentum of this particle with an accuracy greater than the ratio mentioned above allows. Quantitatively, the impulse uncertainty should be such as to satisfy the inequality Δp × Δx ≥ h / 4π. As we will see in the next section, an excellent example of the implementation of the uncertainty principle is an atom. It is difficult to give a more illustrative example, since the typical uncertainty of coordinates is much smaller than the size of any object that can be taken in hand. This is due to the fact that the value of Planck’s constant is extremely small. We will return to it again when we talk about photons, and then I will tell you its numerical value.

Despite the fact that usually when discussing the principle of uncertainty, we are talking about measurements of coordinates and momentum, its essence is much deeper. It is an internal constraint imposed on the concepts of coordinates and momentum. Ultimately, the impulses and coordinates are not numbers. These are more complex objects called operators; and I will not try to describe them here, but only to say that operators are widely used mathematical constructions, only more complex than numbers. The uncertainty principle arises from the difference between numbers and operators. The value Δx is not just the uncertainty of measuring the coordinates, it is the fundamental fatal uncertainty of the position of the particle. In other words, the principle of uncertainty reflects not a lack of information, but a fundamental “fuzziness” of the subatomic world.

»More information about the book can be found on the publisher's website.

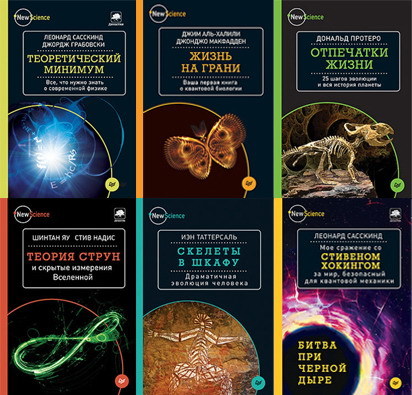

Our New Science series

Pop Science Series

25% discount on books from the coupon series - Geek magazine

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/369731/

All Articles