Physicists hang a mirror of 2,000 atoms near fiber

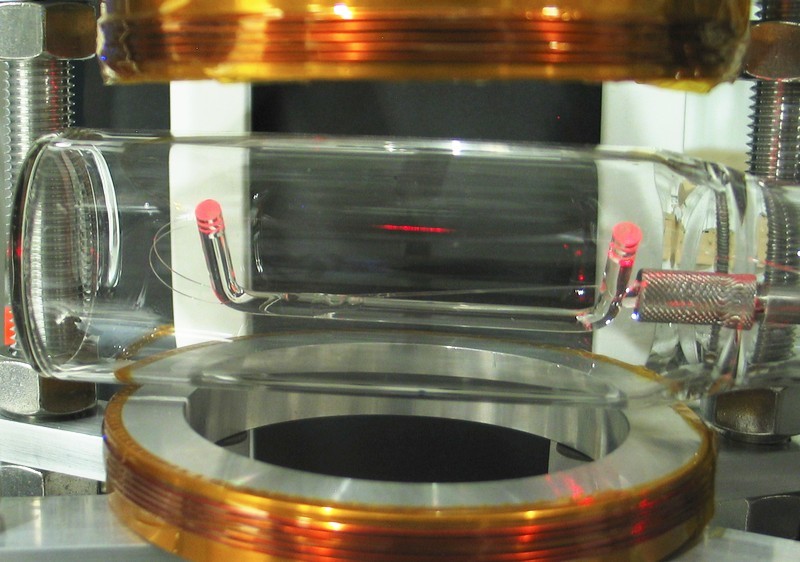

A beam of red light passes through a 400 nanometer fiber. The cesium atoms trapped near the fiber channel send 75% of the light inside the fiber back to the source. The size of the red segment is about 1-2 cm. Photo: University of Pierre and Marie Curie

Mirror - the simplest device for manipulating light. Usually it is a large flat surface. For the history of mankind, people have tried several technologies for the manufacture of mirrors. The ancient inhabitants of Anatolia, Mesopotamia and Egypt polished obsidian and copper in 6000-4000 BC. The production of glass mirrors in Europe was mastered in the 13th century in Holland, and in the 15th century, Venetian merchants bought out a patent and received a monopoly on the production of expensive high-quality mirrors.

To date, no one has set the task to create a minimum size mirror. This was not necessary until the 21st century, until physicists thought about the practical application of quantum electrodynamics.

Experimental installation. Photo: Pierre and Marie Curie University

')

A group of researchers from the Laboratoire Kastler Brossel-LKB laboratory at the University of Pierre and Marie Curie (Paris, France) managed to create an effective mirror of just 2,000 atoms. They described their work in a scientific article on September 23, 2016 in the journal Physical Review Letters (doi: 10.1103 / PhysRevLett.117.133603).

If we describe the discovery in brief, the scientists carefully positioned cold atoms in the optical fiber in order to achieve the necessary conditions for the appearance of the Wulf-Bragg reflection (known in Western countries as the Bragg reflection ).

In 1913, Australian physicist William Lawrence Bragg and Russian physicist George Wolf from the Chernihiv region independently derived a formula for directing diffraction maxima on a crystal of elastically scattered X-rays. William Bragg and his father, William Henry Bragg, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915 for this discovery.

In the experimental setup of the French scientists, each of the carefully spaced cold atoms makes a small contribution to the refraction of light. Due to constructive interference and multiple reflections, the entire structure of 2,000 atoms jointly is able to send about 75% of the incident photons back to the source.

This is a significant step forward in the development of nano-mirrors, because previous attempts to create a miniature mirror required the presence of millions of atoms.

Based on the reflection conditions of the Wulf-Bragg it is perfectly clear how atoms should be arranged in order to create constructive interference with each other. The question was how to place them exactly in these positions. Here, researchers have applied the latest advances in controlling atoms with one-dimensional boson waveguides (waveguide is the guide channel in which the wave propagates). You can learn more about these achievements by studying the scientific works published in 2007-2015: 1 , 2 , 3 . In addition, they used the latest experimental research in the development of one-dimensional dielectric waveguides to control cold atoms trapped .

Thus, it remained to take the last step: to combine the design of one-dimensional waveguides with a controlled lattice of atoms. In this case, the atomic lattice is able to manifest an unusual phenomenon of the joint effect on photons. If desired, you can make a mirror based on the reflection of Wulf-Bragg, which carried the French.

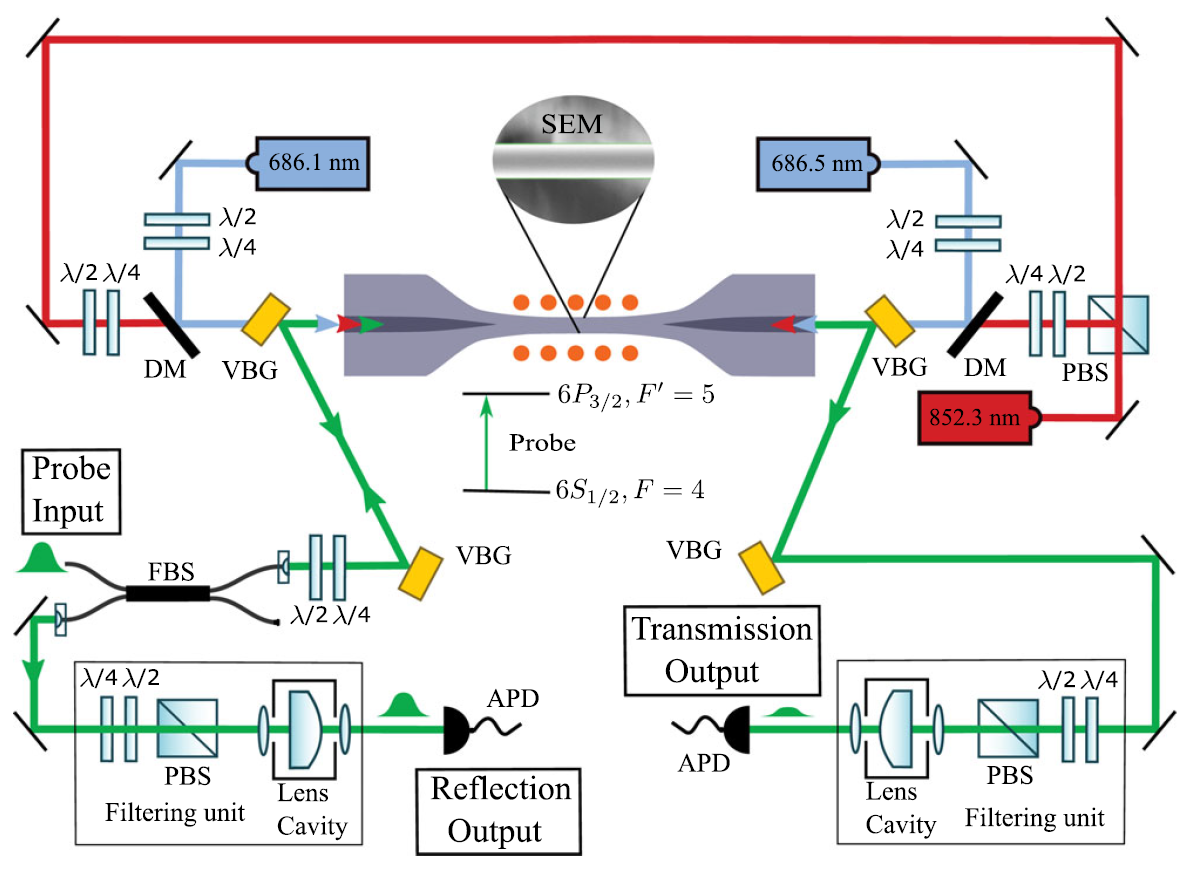

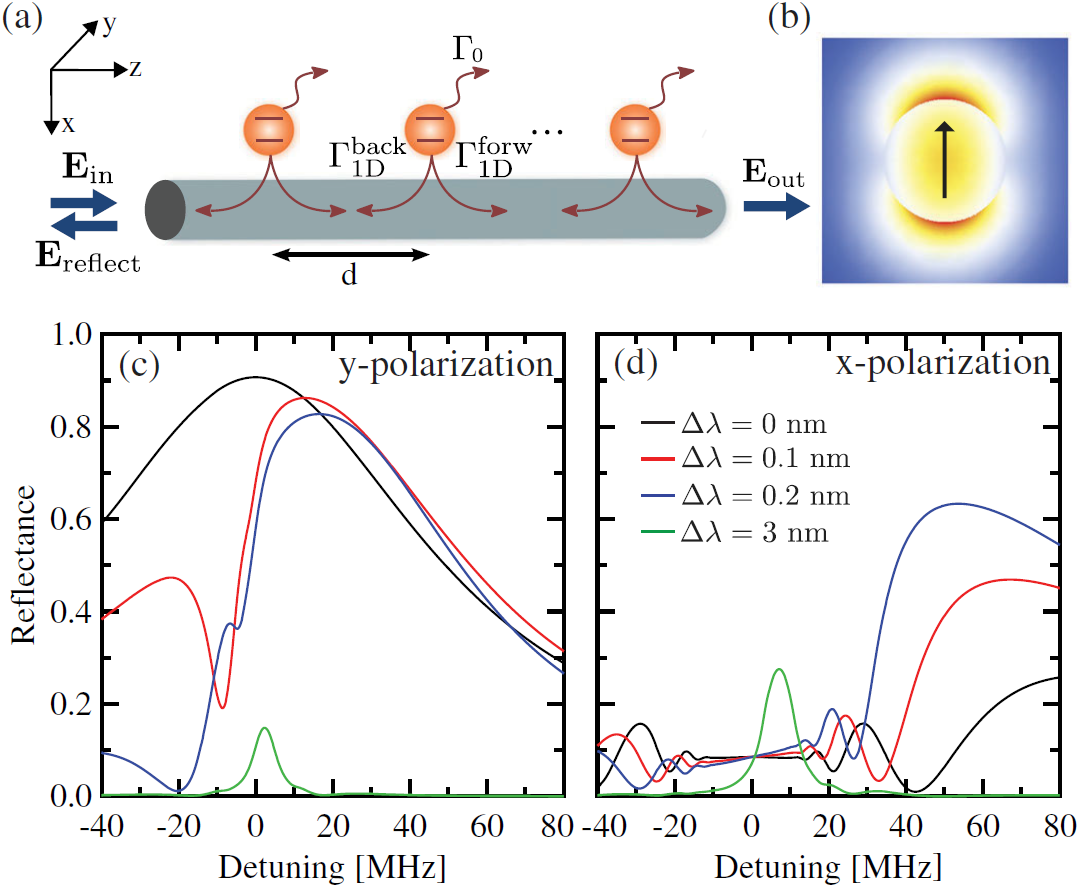

Experimental setup: a series of cesium atoms (red circles) trapped in the vicinity of the fiber. The traps are organized by a pair of oncoming red rays, close to resonance (standing waves), as well as an additional pair of blue rays that perform auxiliary repulsion. Illustration: Pierre and Marie Curie University

With the passage of light along a 400 nm thick optical fiber, a significant part of the light goes beyond the limits of the optical fiber and goes near it. With the help of this light, physicists built a dipole trap for cold cesium atoms. Carefully picking up a pair of rays, they generated two chains of capture potentials around the optical fiber in such a way that only one specific place was intended for each atom. By controlling the color of the rays (that is, the wavelength), physicists were able to choose the distance between the atoms so that it was as close as possible to the half of the resonance wavelength of the cesium atoms. Thus, a grid of 2,000 atoms near the fiber effectively reflects light inside the fiber.

In the illustration: (a) Wolff-Bragg reflection from atoms trapped by a one-dimensional waveguide near the optical fiber; (b) the distribution of the density of the electric field in the cross section of an optical fiber with quasilinear polarization (the direction is indicated by the arrow); ©, (d) theoretical reflection spectrum. Illustration: Pierre and Marie Curie University

This is a very important step in a new and promising area of research - the use of waveguides in quantum electrodynamics. One can easily imagine exactly how this discovery will be applied in numerous practical areas, including optical memory for computers, quantum networks, quantum nonlinear optics, and quantum simulators .

Who knows, suddenly the atomic mirrors on the waveguides will almost become the subject of everyday life.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/369719/

All Articles