Ask Ethan # 89: Dark Ages of the Universe

After KMFI and before the first stars appeared, there was nothing to see in the Universe. Or is it not?

If there was no light in the Universe, and, consequently, no creatures with eyes, we will not know if it was dark. Darkness in this case does not make sense.

- Clive Staples Lewis

Last week we answered the question about the location of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMF). In short, it is “everywhere at the same time, but it was emitted at the time when the universe was 380,000 years old.” This week I chose a question from Steve Limpus, which opens a new step in the same topic:

Please tell us about the time immediately after KMFI - about the mysterious “dark ages”. I wanted to know how gravity affected the expanding Universe in times after inflation and the thermal equilibrium of particles [decoupling]. And I would also like to know about the first stars and the formation of galaxies and supermassive black holes.

At the beginning and now there is an abundance of light with high energies: the light visible by our eyes. But there were times - dark times - when there was no light.

Today, of course, the universe is full of different structures, including heavy elements, organic molecules, moons, planets and life. On a large and luminous scale, there are stars, clusters, galaxies, clusters of galaxies, supernovae, quasars and a huge cosmic network. There are quite luminous objects in almost any direction anywhere in space. We, apparently, are limited only by the size of telescopes and the amount of time spent on observation.

If you look at the most distant object that we can see, we will find KMFI in all directions.

')

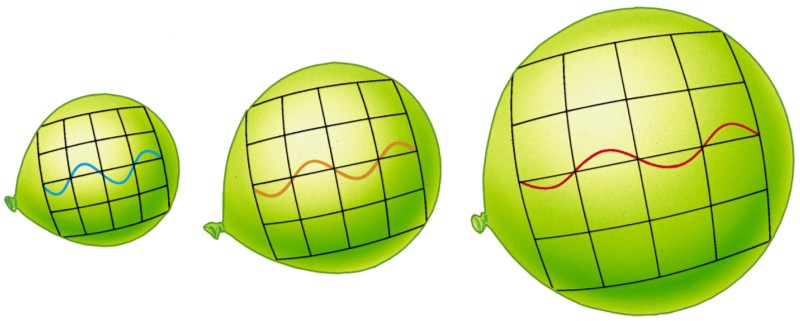

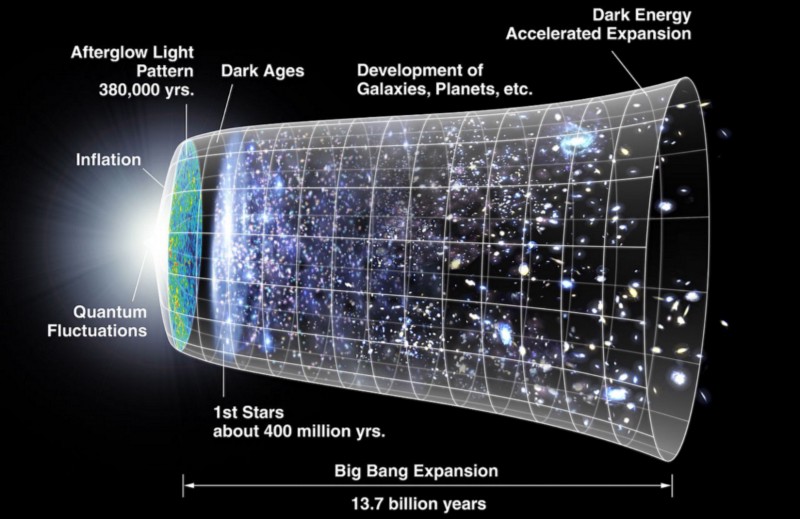

In the early stages of the Universe - during the hot Big Bang - the Universe was filled with everything that was available energetically: photons, matter, antimatter, and, perhaps, a huge number of particles, the existence of which is still unknown to us. Over time, the universe expanded, which continues today. During expansion, the Universe cools, because the amount of photon energy is inversely proportional to its wavelength: stretch the photon wave as the universe expands and it cools.

This cooling means that at some point it becomes cold enough to:

• the spontaneous appearance of matter / antimatter vapors ceased, and all excess antimatter could annihilate,

• atomic nuclei, consisting of protons and neutrons, could form and not be immediately broken up into parts,

• neutral atoms could be formed whose electrons would not be knocked out from orbits.

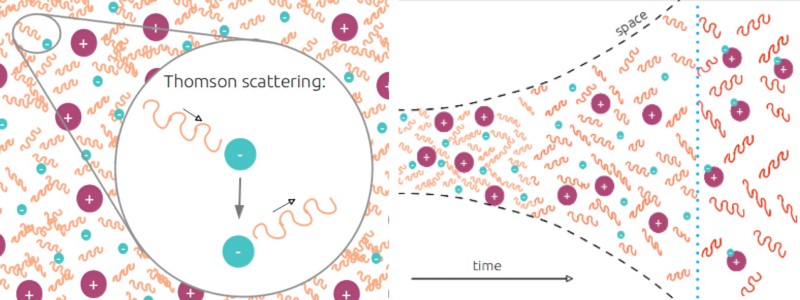

The last step is extremely important, because after this transformation, the Universe moves from an opaque ionized plasma, where photons are constantly scattered by electrons, to a transparent state, where photons freely propagate. In this they do not interfere with the neutral atoms, while remaining themselves virtually invisible.

So the last scattering surface, KMFI, appears. First formed, it has a temperature of 2,940 K, corresponding to red. Over the next three million years, the CMBR light undergoes a red shift from the visible range into the infrared, and then into the microwave. But from the moment when the Universe emitted KMFI, being 380,000 years old, and until the formation of the first stars tens of millions of years later, no new light appeared in the Universe that we could see. This time is known as the "dark ages."

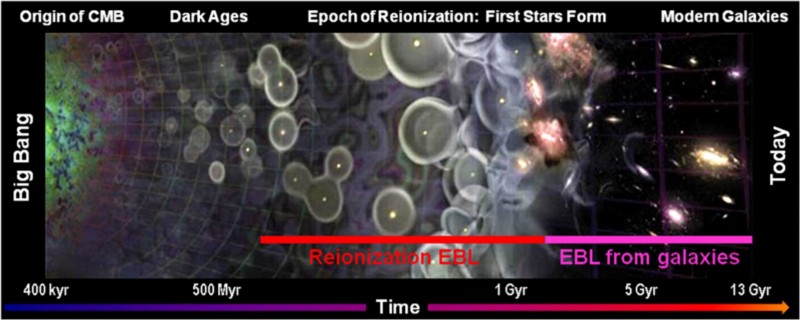

Steve asked a lot about what, including the formation of stars, galaxies and black holes. I have bad news: all this happens at the end of the dark ages, in the era of the second light. If the Big Bang gave off the first light, then before the first stars appeared there were no other sources, and this happened only when the Universe was from 50 to 100 million years old. (You could hear the figure of 550 million, but this is the time of the reionization of the Universe, and not the appearance of the first stars!).

Only after the formation of the first stars did the first black holes appear (after the death of the stars), the first supermassive black holes (from the star associations), the first galaxies (from the star clusters associations), and larger structures. But what happened at that time, between KMFI and the first stars? Was there anything interesting?

There are two positive answers to this question, one of which is the most interesting.

1) Gravitational growth turns tiny, one part per 30,000, areas with increased density, into the first stars of the Universe. The fluctuations in KMFI are not only beautiful patterns found by the COBE, Boomerang, WMAP and Planck projects. These “hot spots” (red) are regions where there is slightly less matter in the Universe, and “cold” (blue) ones where matter is slightly more than average. Why? Because, although KMFI is the same everywhere, it needs to get out of the gravity wells, and the more matter you have, the further you need to get out, and the more energy you will lose.

The cold areas attract more and more matter - they grow over time - while the growth rate increases as matter becomes more and more important, and radiation - less and less important. By the time the Universe turned 16 million years old, typical high-density areas had increased 10-fold compared with the surface of the last scattering. Those whose density was 1 part at 30,000, reached a density of 1 part at 3000; plots with a density of 1 part per 10,000 turned into plots with a density of 1 part per 1000, and super rare large fluctuations, the density of which at the time of the CMBI was 1 part per 500, show a density of 1 part per 50, or 2% more dense than the average . Over time, these areas of increased density grow. There is a threshold value that radically changes the picture. When a region of increased density becomes 68% denser than the average, its growth becomes nonlinear, that is, the gravitational accumulation of matter accelerates rapidly.

Passing this threshold, you are on the path to creating stars; from transition to the appearance of the first stars will most likely pass no more than 10 million years. Therefore, tens and hundreds of millions of years can pass before a significant increase in density, but to achieve this value, the illumination of space depths becomes a matter of not so long waiting. The era of the second light is coming, and the dark ages, the only period when there was no visible light in the universe, ends.

But the dark ages of the universe are in fact not 100% dark. Of course, there is no visible light, but a little light appears even before the formation of the first star - all due to the simplest structures of the Universe, modest and simple neutral atoms.

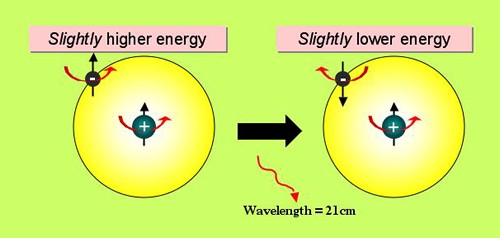

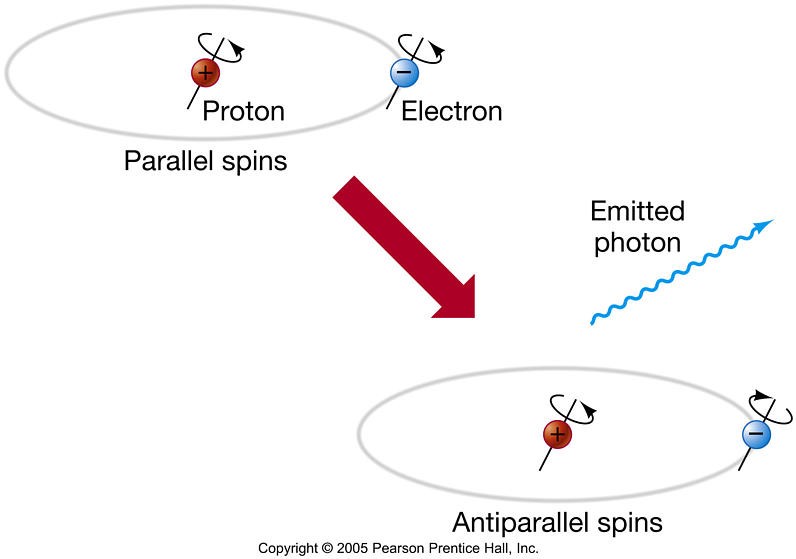

2) These same neutral atoms, 92% of which were hydrogen atoms, slowly emit light at a perfectly accurate radio wave of 21 cm. The hydrogen atom is usually represented as a proton with an electron orbiting around it. This is a very accurate picture that is true both today and 100 years ago, when Niels Bohr first developed this model for a hydrogen atom. But one of the properties of protons and electrons is often ignored, despite the fact that in dark ages it has a special importance: they have a spin, or an inherent angular momentum.

For simplicity, we denote the property of the back to be in the "up" or "down" position, so if your proton is connected to an electron, they will be oriented either the same way (up-up or down-down) or oppositely (up-down or down-up) . Mutual orientation is formed randomly, and depends on what the protons did with the electrons when you created hydrogen: usually 50% are oriented the same way, and 50% are vice versa. Between the two states there is a tiny difference in energy - corresponding to the amount of photon energy with a wavelength of 21 cm, or 5.9 µeV - but the transition from high-energy (aligned) to low-energy (opposite-oriented) state is prohibited by the laws of quantum mechanics.

Only as a result of an extremely rare process , a transition that takes an average of 3.4 × 10 15 seconds (11 million years), an atom can go from an equally oriented state to the opposite, emitting a photon with a wavelength of 21 cm.

This spin-flipping transition was never observed in the laboratory due to these time gaps, but was discovered astronomically in 1951. This is a very important phenomenon used to mark up properties for which the light is not suitable. This is how we first marked the spiral structure of our Galaxy, because of the dust, visible light does not pass through it. Similarly, we measured the rotation curves of galaxies at large distances; 21 cm line is a very powerful astronomical instrument.

One of the goals of astronomy of the future is the construction of a telescope supersensitive to the 21-cm line, which will enable us to construct a map of the universe in dark ages; nobody has done this yet. This will allow us to look beyond the horizon of the visible, the era of reionization, and at that time, when the first stars that James Webb’s telescope hopes to see are not yet formed.

Dark Ages is a good name, but we have a chance to light them using the weakest energy of light, light, the wavelength of which should be tens of meters due to the redshift - which means we will need a telescope of no smaller size. Ideally, we need an Aresibo-type telescope, but in space, away from terrestrial radio interference.

There are other possibilities, one of which is described by Amanda Yoho . That's the whole history of the cosmic dark ages! Thank you for the wonderful question, Steve. Send me your questions and suggestions for the following articles.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/369661/

All Articles