Andy Grove and the turning points of Intel history

About a month ago, one of the founding fathers of Intel, employee number three Andy Grove, died in the 80th year of his life. We could not get past this unfortunate event, because Andy is not just a man who has held the highest positions in Intel for 30 years. It was with his help that the corporation managed to overcome the crisis, turning points in its history, when it was necessary to take a serious, sometimes difficult decision, feeling for it its responsibility. All companies pass through such moments, and the larger their size, the higher the qualification and the better the intuition of the top manager should be, so that this crisis does not end up last.

In this post, we present abbreviated excerpts from Grove’s book. Only paranoids that describe three critical moments in Intel’s history that “resolved” Grove survive : leaving the memory chip market, choosing between RISC and CISC, and the problem with FPU Pentium. And also we will show the rarest photos from the Intel archive.

1985 Leaving the memory chip market

We started small. Intel's first product was 64-bit memory. No, this is not a typo. It could store 64 binary numbers. Then we focused all our efforts on the development of another chip - 256-bit memory. As a result of the enormous efforts soon after the first one, we presented the second model. These models were a miracle of the technology of 1969, but there were few orders for industrial production. At that time, semiconductor memory modules were just a wonder. So we continued to develop the next model of chips, which was four times more complicated and memorized 1024 characters. After the struggle with the first two technical curios, which were not sold, and the third, which was sold, but the production of which gave us a huge amount of problems, Intel became a company, and memory modules became a separate industry. As pioneers, we owned almost 100% of the memory module market.

Then, in the early 80s, Japanese manufacturers took the stage. People returning from Japan told horrible stories. For example, they said that in one large company the department of development of memory modules occupied an entire building and its specialists worked on models of different generations at the same time. 16 Kbit modules were made on one floor, 64 Kbit on the next, and even higher were people who designed 256 Kbit memory modules. There were even rumors that work was underway on a 1 million-bit memory module. It was all terrible in terms of a small company from the city of Santa Clara, California. Then we were hit in quality. Managers of Hewlett-Packard made a statement that the quality level of Japanese memory modules consistently exceeded the level of American counterparts. As often come in a similar situation, we vehemently denied the threatening data. Only when we were convinced that we were generally right, we returned to work on the quality of our own products. But by this time we were already far behind.

We bravely fought. We increased the quality and reduced the prices, but the Japanese manufacturers answered the same. Their main weapon was the availability of high-quality products at incredibly low prices. Once we got a directive addressed to the sellers of a large Japanese company, the text of which read: “We will win using the 10% rule ... Find Intel chips ... Set a price 10% lower than them ... If they lower prices, slow down 10% ... Do not stop until you win! ” We tried a lot. We tried desperately to win for our products the title of the best on the market, since we could not keep up with the decline in prices by Japanese companies. At that time, Intel had a saying: “If everything goes well, we will be able to sell memory modules twice as expensive as the Japanese. But what do we get as a result? After all, their prices are becoming lower. "

')

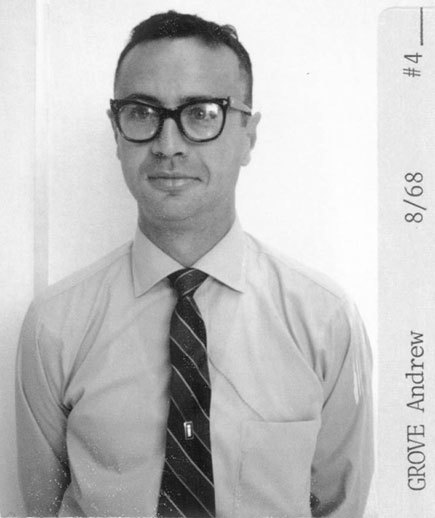

The first photo of Grow as an employee of Intel. It is curious that due to still unclear reasons, the legally owned number 3 went to employee Number 4 Les Vadasz, and before the end of his career at Intel, Andy had ID 10000004

More importantly, we continued to invest heavily in research and development. Most of the funds went to the memory modules. At the same time, a small group was working on the technology of another device, which we invented around 1970, the microprocessor. Microprocessors are the brain of a computer, they make calculations, and memory modules simply store information. Microprocessors and memory modules are created using the same silicon chip technology, but differ in their design. And since the microprocessor market was small and slowly growing compared to the market of memory modules, we did not pay much attention to these developments.

I remember the middle of 1985. By that time, we had been wandering for a year. I sat in my office with the chairman of the board of directors and the general director of Intel, Gordon Moore, and discussed with us our predicament. Our mood was gloomy. I asked: "If we were fired and the board of directors chose a new CEO, what would he do, do you think?" Thinking, Gordon replied: "He would lead us out of the memory module market." I stared at him in astonishment, and then said: “Why don’t we go out the door and, returning, don’t do it ourselves?” With these words and with the encouragement of Gordon, we embarked on a very difficult path. After long and painful deliberation, we instructed our sellers to communicate this news to customers. That was the worst thing: how would they react? Will they stop doing business with us after we let them down? In reality, the reaction was complete indifference. Our clients knew that we do not play a big role in the market, and we have long understood that we are going to leave it. When we informed them of our decision, some said: “It took you a lot of time.” People who are not emotionally involved in decision-making, much earlier understand what needs to be done.

When we entered this door, the question arose: if we do not deal with memory modules, then what will we focus on in the future? The obvious candidate was microprocessors. For five years, we have supplied microprocessors for IBM-compatible personal computers; we were the biggest player in the market. Moreover, our next main microprocessor, the 386th, was ready for production. What happened next? The 386th processor became very, very popular, much more popular than other microprocessors of that time. We owe much of its success to the former group of developers of memory modules. We were no longer a semiconductor memory module company. When we began to search for a new direction for the corporation, we realized that all our efforts at that moment were devoted to microprocessors. We have identified ourselves as a "microprocessor manufacturing company."

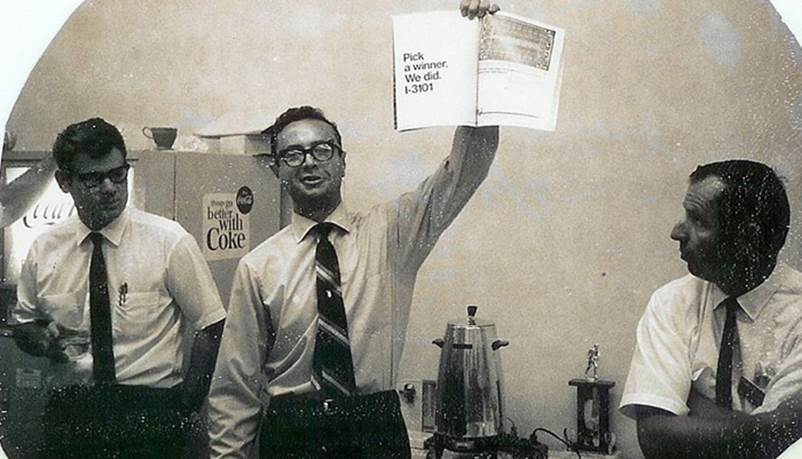

1969 Andy shows off Intel 3101 magazine advertising - Intel's first 64-bit memory module

1989 RISC or CISC, i860 vs. i486

Intel processors have historically been based on CISC schemas. By the end of the 80s, when other companies turned to the RISC scheme, the 386th Intel microprocessor had already entered the market, and the next generation of processors was under development. The 486th processor was a more advanced version of the same architecture that we used in the 386s. It was extremely important for Intel: we believed (and believe) that all our microprocessors must be compatible with the software that our customers bought for their previous microprocessors.

Some of our employees believed that the RISC methodology would provide an opportunity to improve the work 10 times. Such indicators in the hands of our competitors would threaten our core business. Therefore, just in case, we started developing a highly efficient microprocessor based on RISC technology. However, this project had its drawbacks. Although the new RISC microprocessor was faster and cheaper, it was incompatible with most software on the market. Engineers and technicians who considered RISC to be a more advanced technology disguised their efforts, proposing to develop a new processor as an additional one to the 486th. Of course, they hoped that the capabilities of the new technology would raise their processor to new heights. Anyway, the project was launched, and soon a new and very powerful microprocessor appeared - i860-ft.

Now we had two powerful microprocessors, which we presented almost at the same time: the 486th, based on CISC technology and compatible with all software, and i860-ft, based on RISC technology, very fast, but not compatible with nothing. We did not know what to do. Therefore, we presented both models, leaving buyers the right to choose. However, it was not so simple. We had two completely different competing products in our hands, each of which demanded more and more internal resources. The struggle for resources and market attention led to internal disputes that were so strong that they tore our company apart. Meanwhile, our hesitations puzzled our customers, who could not understand what kind of processor — the 486th or i860th — supports Intel.

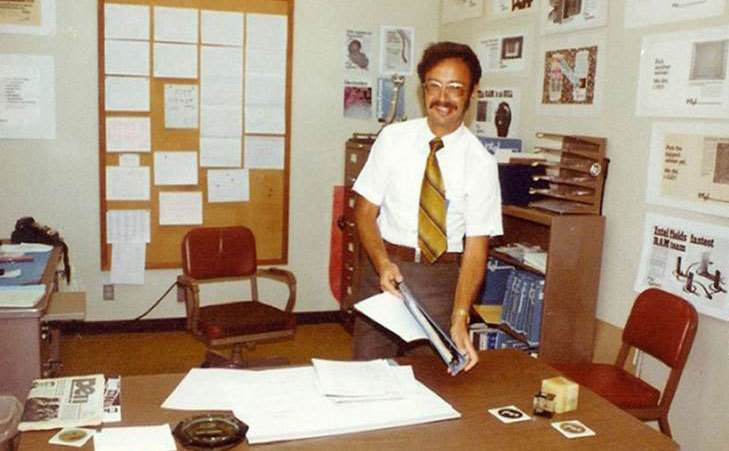

1971 Andy Grove at Intel Factory

I watched with growing anxiety. Problems touched the heart of our company - the microprocessor business, in which we invested our faith and on the basis of which we reorganized the company. The fantastic popularity of the 386th could well inherit the 486th, and possibly future generations of microprocessors. Should we give up a good thing, which, at least, is good now, and return to competition with other manufacturers of RISC processors - a fight in which we did not have particular advantages? Our customers and partners also could not make a choice. On the one hand, Compaq's CEO, one of our most important customers, convinced us to continue our efforts to improve the performance of our old CISC microprocessor line. He was convinced that this architecture had the potential to live until the end of the decade. On the other hand, the chief technology manager at Microsoft was pushing us towards the “860th PC.” As the head of one European company, our client, told me: “Andy, this is like a model business. We need something new. ”

The reaction of consumers to the official presentation of the 486th processor was extremely supportive. I remember, I sat at the presentation of the processor in Chicago with prominent figures of the computer world, each of whom spoke about his readiness to create computers based on the 486th processor, and thought: “RISC or not RISC, but we could not put all our efforts to to consolidate this success. ” Thus, the choice was made, disputes ceased, and we concentrated all our efforts on the 486th processor and subsequent models.

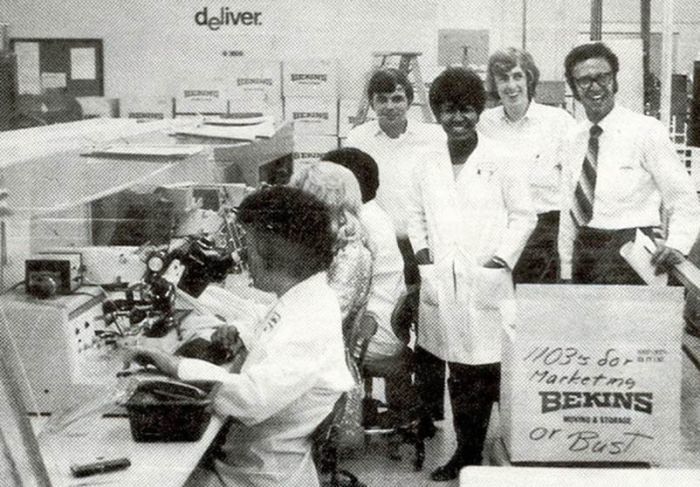

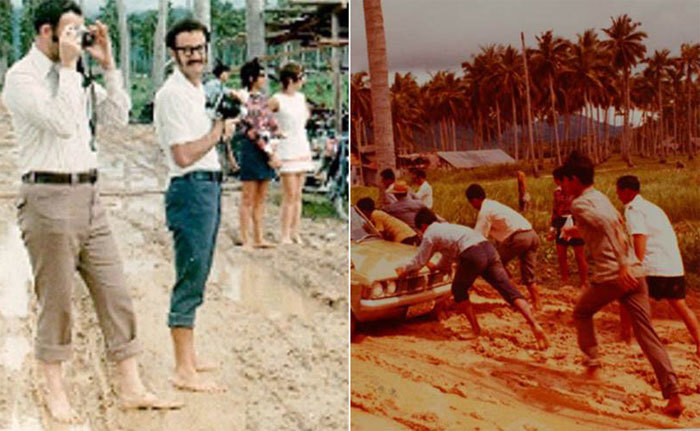

1972 During the construction of the first overseas office in Malaysia, Grove learned from experience what the rainy season in Asia is. In the right photo, he pushes the car in the background, wearing a white shirt.

1994 year. Error in FPU Pentium

On the morning of Tuesday, November 22, 1994, on the eve of Thanksgiving, I had a phone call. The head of our PR department wanted to talk to me urgently. She told me that a group from CNN was coming to us. Journalists found out about the error in the Pentium processor's floating point computing unit and were going to fan this story. A few weeks earlier, our employees read a number of statements on the Intel Internet forum under the heading “FPU Error” (FPU - “floating point computing unit”). They appeared after one mathematics professor found a flaw in the Pentium processor: according to him, in the process of studying some complex mathematical problems, he encountered an error in division. We already knew about this problem because we discovered it several months earlier. The error in rounding during division, which occurred in one case out of nine billion, was due to a small error in the processor circuit.

That day, a CNN film crew appeared. They wanted to talk to us and seemed to be belligerent. The director began a preliminary conversation with our PR department with accusations, his tone was rather aggressive. The next day, CNN showed on TV a very unpleasant storyline. After a day, articles began to appear in each major newspaper, which ranged from “The error will affect the accuracy of Pentium processors” to “The Pentium problem: buy or not buy”. Our headquarters was besieged by television journalists. The flow of Internet messages has increased many times. It seemed that all Americans were connected to this discussion, and soon users from other countries of the world joined it.

Owners of computers began to call us with a request for replacement processors. Our replacement strategy is based on an assessment of the problem. People, whose work implied a large number of division operations, processors exchanged. We tried to reassure others by using the results of our research, offering to send them official conclusions. This tactic has borne fruit - the number of daily calls has decreased. But then there was the message of the telegraph agency. It consisted of only one phrase, which sounded like this: “IBM stops supplying all computers based on Pentium processors”. Almost all thirteen years after the appearance of the IBM PC was the most significant player in the industry, so its actions attracted such attention. The nightmare was repeated.

1988 year. Grove at the opening of the first showers for Intel employees

For me, this time was not easy. I have been working at Intel since its inception and have experienced several serious crises, but now the situation was much more complicated. I felt that we were under siege, under fierce shelling. Why did this happen? Intel's headquarters was conference room No. 528, located twenty feet from my office. After a few days of fighting public opinion, answering phone calls and offensive articles, it became clear that something had to be changed seriously. We decided to exchange processors to all who require it. Within a few days, we almost from scratch created a special department for answering phone calls. Initially, our workforce consisted of volunteers: designers, marketers, programmers. They threw down their affairs, sat at improvised tables, answered phone calls and wrote down names and addresses.

In the end, we have accumulated a huge amount of marriage, almost 475 million dollars. It was equal to the semi-annual budget of the department of research and development or the cost of advertising the Pentium processor for five years. So we stepped on a completely new way of doing business.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/368749/

All Articles