Treasury of domestic cryptography

In my first article I wrote about the legendary Bletchley Park and the cryptographic service of Great Britain during the war period, about the Turing encryption machines and the German Enigma. Now we will talk about our domestic cryptography. In the USSR, cryptography was a completely closed discipline, which was used exclusively for the needs of defense and state security, and therefore there was no need for publicizing the achievements in this field.

Many would agree with the American historian David Kahn that "the encryption business got its modern look thanks to the telegraph."

Russia. The end of the nineteenth century. 1879 The chief mechanic, assistant chief of the St. Petersburg postal and telegraph district Derevyankin developed an original device for encrypting Cryptograph telegrams. This device resembled the famous Renaissance era encoder - Alberti's disk . An Italian architect, philosopher, painter Alberti, in the 16th century, created his own cipher, which he called "a cipher worthy of kings." The encryption disk itself was a pair of disks, one of which is vernal, immobile, the second is internal, movable. On the outside were alphabetic letters and numbers from 1 to 14; on the inner letters were swapped. The encryption process consisted in finding the letter of the plaintext on the external disk and replacing it with the corresponding letter of the ciphertext under it. After encrypting a few words, the internal disk was moved one step. The key was the order of the letters on the internal disk and its initial position relative to the external disk.

Other primitive cryptographic devices were also used, in which multi-alphabetic replacement was mainly implemented. The work with the Lambda cipher was facilitated by the Scala Mechanical Cipher and developed in 1916 by Second Lieutenant Popov, the encryption device Vavi Device. "Scala" - a wooden device contained a vertical celluloid llama with ten empty cells, the size of which coincided with the length of the cipher columns in the book. The cipher entered the numbers corresponding to the specified key (column number) into the llama cells and applied the device sequentially to the cipher columns. Each time, a substitution for encryption was obtained.

The number of the initial column is encrypted. To do this, the cryptographer wrote down the number of the original column three times in a row (3x4 = 12 digits) and added the twice-recorded number of the last used column (with the aim of helping to decipher the text in case of any failures or errors). The result was a “pointing row” of twenty numbers. For example: 2563 2563 2563 4812 4812. Next, the column indicated as the key by the cypher branch (column written on the llama) and the column next to it (10 + 10 = 20 digits) were taken. This sequence, called the “calendar row”, was signed under the index row and was subtracted modulo 10. The resulting series was inserted into the cryptogram in a conditional place. The “ Wavi device ” was made according to the anology of the “Jefferson device” , but instead of the discs, 20 rings were used closely mounted on the cylinder, the first and last edges were marked with numbers from 1 to 30 in order, and the rest were mixed by 30 letters. Given the arrangement of the disks, the key was a number, a letter and a “key of the step” - two letters, the message was divided into parts of 17 letters each, the disks were set so that the key and 17 letters of the message were on the same line. The ciphertext was read letter by letter and alternately from the lines in which the letters of the key of the step were on the second disk.

The Scala device with the inserted llama and the first page of the Lambda re-encryption key

')

Jefferson apparatus

example of the “apparatus of Wawi”

After the victory of the October Revolution, insufficiently strong manual encryption systems were used. A lot of the encrypted information of the Red Army (Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army) and the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs were successfully read by the White Guards, the Poles, the British, the Swedes. But, and the Soviet cryptographers managed to crack the encryption system of the enemy. May 5, 1921 under the assistance of V.I. Lenin created the Special Department of the Cheka - a single national cryptographic service. Employees of other units were skeptical of the Special Department, as there “they did not arrest or interrogate anyone”. Initially it included 6, later 7 branches, but, actually, only three of them were engaged in cryptographic tasks. The 2nd department was engaged in the theoretical development of questions of cryptography, the development of fonts and codes of the Cheka, consisted of only 7 people. Sotrudyki 3 offices (and there were three of them) were engaged in "cipher work and the leadership of this work in the Cheka." The 4th Division of the Special Department (8 people) was faced with the task of “opening foreign and anti-Soviet fonts and codes, as well as decoding documents”. Already in the 30s, the face was the fact that the existing manual encryption systems (no matter how perfect they were) could no longer cope with the increasing flow of information due to the low processing speed. In order to encrypt an order of the size of one and a half printed pages, it took 4 to 5 hours; the decryption took as much time.

When transmitting text via telegraph channels, mistakes were often made, which, consequently, increased the processing time of information three times. In the interwar years, the development and development of mechanical and electromechanical text encryption machines became “crying-relevant”. It can be said that the era of machine ciphers has arrived. The first electromechanical encoder of domestic production was the equipment for classifying telephone conversations, released in 1927-28. Specialists of the VChK Special Department were well aware of the need to immediately create a cryptographic machine, since World War II was advancing. This meant that it was necessary not only to develop as soon as possible, but also to set up the production of modern encryption machines.

Two samples of the Soviet encryption machine were developed in the technical laboratory of the encryption service under the direction of I.P. Voloska in 1931: ShMV-1 . The car did not go into the series because it was rather cumbersome, and what's worse, mechanically unreliable. At plant number 209 (later named after A. Kulakov) a research and production structure was created for the development and production of special security equipment. The design of the future apparatus was developed throughout the whole year. The B-4 encryption machine was easy to use with a minimal set of controls. Soon it was modernized and received the name M-100 “Spectrum” .

With common foreign counterparts, which worked on the principle of mechanically programmable disk encoders, USSR encryption equipment had little in common. The M-100 encryption machine consisted of 3 main assemblies — a keyboard with contact groups, a tape drive mechanism with a transmitter, and a device mounted on a typewriter keyboard. The total weight of a set of seven packages reached 116 kg. Batteries for autonomous power supply of the electric part of the car weighed 32 kg. Nevertheless, this equipment was mass-produced and was successfully tested in combat conditions during the Spanish Civil War, at Lake Hassan, at Khalkhin-Gol and during the Soviet-Finnish war. The machine encrypted letter telegrams at speeds of up to 300 characters per minute.

In 1939, a new cipher machine with a K-37 Kristall rotary encoder was developed. Such a device weighed 19 kilograms, worked on a multi-alphabetic replacement cipher. K-37 was used in the army communication networks, for classifying telegraph messages. In 1942 M-101 was put into operation, which consisted of 2 units with a total weight of 64.5 kg. The car was named M-101 "Emerald" and began to be produced in parallel with the B-4 and M-100. The B-4 and M-101 "Emerald" devices were considered to be one of the most cryptographically secure encryption devices of their time and were used to provide communications of the highest management level of the strategic level. In addition, "Emeralds" were used in long-range bomber aircraft. It is known that in 1943 90 sets of M-101 machines were supplied to the Soviet troops.

The M-100 and M-101 cipher machines were constructively adders of plaintext characters with signs of the external gamut, which were carried by disposable tapes of a random two-digit code. The basis of the work of mechanical scattering devices was a random selection of balls from an urn with or without a return. However, the harvesting (scattering) devices could, in principle, only form a random and equally probable gamma.

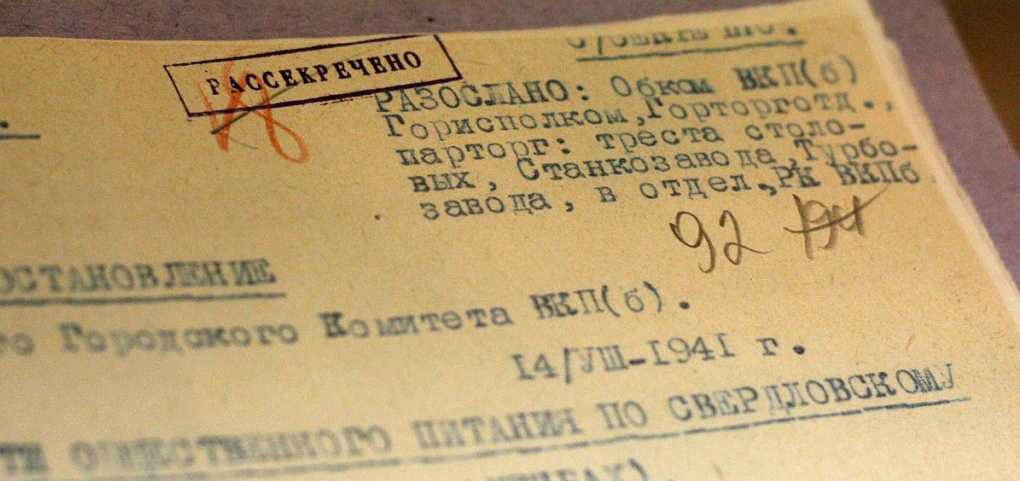

During the war years, Soviet engineers made a breakthrough in the field of encryption. From 1941 to 1947, a total of over 1.6 million encrypted telegrams and codograms were transmitted. As the author of several books on cryptography Dmitry Larin writes, the load on communication channels sometimes reached 1,500 telegrams per day. Cryptographic schools prepared and sent to the front more than 5,000 cryptographers.

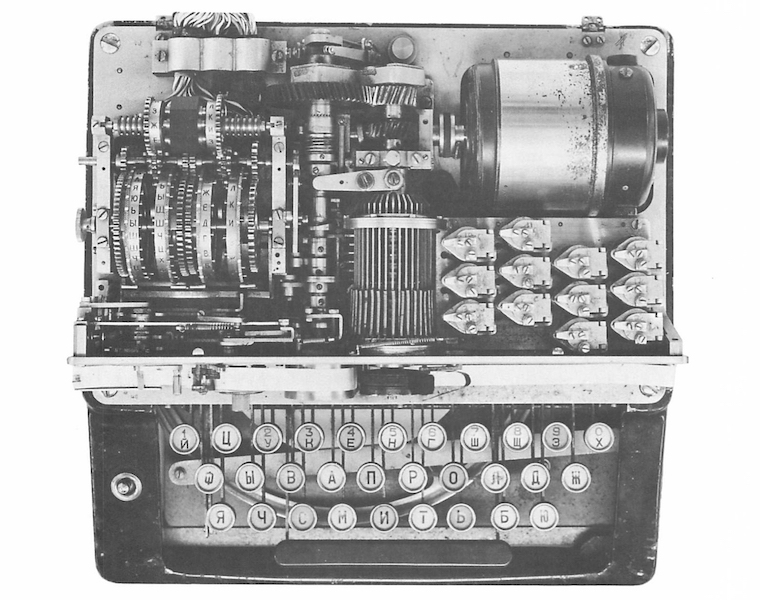

Encoder of the time of the Second World War, but about which it is impossible not to write

A series of successors to the K-37 - rotary cryptographic machines appeared in 1962, the most famous was the 10-rotor M-125 "Violet" , which the USSR supplied to the allies. Violet is often considered the “granddaughter” of Enigma, although there are fewer disks in it, and the wheels rotate in one direction. In addition to the punch cards, letter keys are used, each disk has its own letter, disks on the shaft are respectively typed, then, according to another key, they are put in a specific sequence by rotation. This model is free from the lack of Enigma - the exclusion of the possibility of encrypting a letter by itself. The amazing engineering work with the romantic name "Violet" - the Soviet encryption machine, created in the 1950s, remained unbroken, the highest achievement of engineering for intelligence and counterintelligence.

Cryptographic historian Leonid Butyrsky:

Attempts to create devices for automatic encryption

Many would agree with the American historian David Kahn that "the encryption business got its modern look thanks to the telegraph."

Russia. The end of the nineteenth century. 1879 The chief mechanic, assistant chief of the St. Petersburg postal and telegraph district Derevyankin developed an original device for encrypting Cryptograph telegrams. This device resembled the famous Renaissance era encoder - Alberti's disk . An Italian architect, philosopher, painter Alberti, in the 16th century, created his own cipher, which he called "a cipher worthy of kings." The encryption disk itself was a pair of disks, one of which is vernal, immobile, the second is internal, movable. On the outside were alphabetic letters and numbers from 1 to 14; on the inner letters were swapped. The encryption process consisted in finding the letter of the plaintext on the external disk and replacing it with the corresponding letter of the ciphertext under it. After encrypting a few words, the internal disk was moved one step. The key was the order of the letters on the internal disk and its initial position relative to the external disk.

Other primitive cryptographic devices were also used, in which multi-alphabetic replacement was mainly implemented. The work with the Lambda cipher was facilitated by the Scala Mechanical Cipher and developed in 1916 by Second Lieutenant Popov, the encryption device Vavi Device. "Scala" - a wooden device contained a vertical celluloid llama with ten empty cells, the size of which coincided with the length of the cipher columns in the book. The cipher entered the numbers corresponding to the specified key (column number) into the llama cells and applied the device sequentially to the cipher columns. Each time, a substitution for encryption was obtained.

The number of the initial column is encrypted. To do this, the cryptographer wrote down the number of the original column three times in a row (3x4 = 12 digits) and added the twice-recorded number of the last used column (with the aim of helping to decipher the text in case of any failures or errors). The result was a “pointing row” of twenty numbers. For example: 2563 2563 2563 4812 4812. Next, the column indicated as the key by the cypher branch (column written on the llama) and the column next to it (10 + 10 = 20 digits) were taken. This sequence, called the “calendar row”, was signed under the index row and was subtracted modulo 10. The resulting series was inserted into the cryptogram in a conditional place. The “ Wavi device ” was made according to the anology of the “Jefferson device” , but instead of the discs, 20 rings were used closely mounted on the cylinder, the first and last edges were marked with numbers from 1 to 30 in order, and the rest were mixed by 30 letters. Given the arrangement of the disks, the key was a number, a letter and a “key of the step” - two letters, the message was divided into parts of 17 letters each, the disks were set so that the key and 17 letters of the message were on the same line. The ciphertext was read letter by letter and alternately from the lines in which the letters of the key of the step were on the second disk.

The Scala device with the inserted llama and the first page of the Lambda re-encryption key

')

Jefferson apparatus

example of the “apparatus of Wawi”

After the victory of the October Revolution, insufficiently strong manual encryption systems were used. A lot of the encrypted information of the Red Army (Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army) and the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs were successfully read by the White Guards, the Poles, the British, the Swedes. But, and the Soviet cryptographers managed to crack the encryption system of the enemy. May 5, 1921 under the assistance of V.I. Lenin created the Special Department of the Cheka - a single national cryptographic service. Employees of other units were skeptical of the Special Department, as there “they did not arrest or interrogate anyone”. Initially it included 6, later 7 branches, but, actually, only three of them were engaged in cryptographic tasks. The 2nd department was engaged in the theoretical development of questions of cryptography, the development of fonts and codes of the Cheka, consisted of only 7 people. Sotrudyki 3 offices (and there were three of them) were engaged in "cipher work and the leadership of this work in the Cheka." The 4th Division of the Special Department (8 people) was faced with the task of “opening foreign and anti-Soviet fonts and codes, as well as decoding documents”. Already in the 30s, the face was the fact that the existing manual encryption systems (no matter how perfect they were) could no longer cope with the increasing flow of information due to the low processing speed. In order to encrypt an order of the size of one and a half printed pages, it took 4 to 5 hours; the decryption took as much time.

When transmitting text via telegraph channels, mistakes were often made, which, consequently, increased the processing time of information three times. In the interwar years, the development and development of mechanical and electromechanical text encryption machines became “crying-relevant”. It can be said that the era of machine ciphers has arrived. The first electromechanical encoder of domestic production was the equipment for classifying telephone conversations, released in 1927-28. Specialists of the VChK Special Department were well aware of the need to immediately create a cryptographic machine, since World War II was advancing. This meant that it was necessary not only to develop as soon as possible, but also to set up the production of modern encryption machines.

Two samples of the Soviet encryption machine were developed in the technical laboratory of the encryption service under the direction of I.P. Voloska in 1931: ShMV-1 . The car did not go into the series because it was rather cumbersome, and what's worse, mechanically unreliable. At plant number 209 (later named after A. Kulakov) a research and production structure was created for the development and production of special security equipment. The design of the future apparatus was developed throughout the whole year. The B-4 encryption machine was easy to use with a minimal set of controls. Soon it was modernized and received the name M-100 “Spectrum” .

By that time, some foreign counterparts of the secrets designed in the USSR were already known to domestic specialists. For example, the American installation with a single inversion of the spectrum was used at the Moscow radio telephone center, and the Siemens encoder was tested in 1936 on the Moscow – Leningrad highway; there was also a brief advertising description of the Siemens mobile phone coder. However, complete and reliable information on foreign encoders was needed: the possibility of placing orders for the development of new equipment or the purchase of finished products was considered. At Technopromimport and the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Trade at the beginning of 1937, more than a dozen European firms were making equipment for over-the-line telephony, including Siemens & Halskey Lorenz (Germany), Bell Telephone (USA) and Automatic Elektric (Belgium), Standart Telephone and Cables (United Kingdom) Hasler (Switzerland), and

also Ericsson (Sweden).

With common foreign counterparts, which worked on the principle of mechanically programmable disk encoders, USSR encryption equipment had little in common. The M-100 encryption machine consisted of 3 main assemblies — a keyboard with contact groups, a tape drive mechanism with a transmitter, and a device mounted on a typewriter keyboard. The total weight of a set of seven packages reached 116 kg. Batteries for autonomous power supply of the electric part of the car weighed 32 kg. Nevertheless, this equipment was mass-produced and was successfully tested in combat conditions during the Spanish Civil War, at Lake Hassan, at Khalkhin-Gol and during the Soviet-Finnish war. The machine encrypted letter telegrams at speeds of up to 300 characters per minute.

In 1939, a new cipher machine with a K-37 Kristall rotary encoder was developed. Such a device weighed 19 kilograms, worked on a multi-alphabetic replacement cipher. K-37 was used in the army communication networks, for classifying telegraph messages. In 1942 M-101 was put into operation, which consisted of 2 units with a total weight of 64.5 kg. The car was named M-101 "Emerald" and began to be produced in parallel with the B-4 and M-100. The B-4 and M-101 "Emerald" devices were considered to be one of the most cryptographically secure encryption devices of their time and were used to provide communications of the highest management level of the strategic level. In addition, "Emeralds" were used in long-range bomber aircraft. It is known that in 1943 90 sets of M-101 machines were supplied to the Soviet troops.

The M-100 and M-101 cipher machines were constructively adders of plaintext characters with signs of the external gamut, which were carried by disposable tapes of a random two-digit code. The basis of the work of mechanical scattering devices was a random selection of balls from an urn with or without a return. However, the harvesting (scattering) devices could, in principle, only form a random and equally probable gamma.

It was clear that the unique Russian machine encryption system could only be vulnerable if the encryption equipment itself and the keys to it were available. Troop coders had to work in exceptional conditions - under fire, in trenches, stacks, dugouts, at night with kerosene lamps or candles. In accordance with the instructions of the General Staff, they were provided with enhanced security. It happened that, instead of guarding, the cipherman set a canister of gasoline in front of him, put grenades next to him and took a pistol from a holster.

The order of Hitler for the Wehrmacht of August 1942 read: "Whoever captures the Russian cryptographer, or captures the Russian cryptographic technology, will be awarded the Iron Cross, home leave and provided with work in Berlin, and after the end of the war - the estate in the Crimea"

During the war years, Soviet engineers made a breakthrough in the field of encryption. From 1941 to 1947, a total of over 1.6 million encrypted telegrams and codograms were transmitted. As the author of several books on cryptography Dmitry Larin writes, the load on communication channels sometimes reached 1,500 telegrams per day. Cryptographic schools prepared and sent to the front more than 5,000 cryptographers.

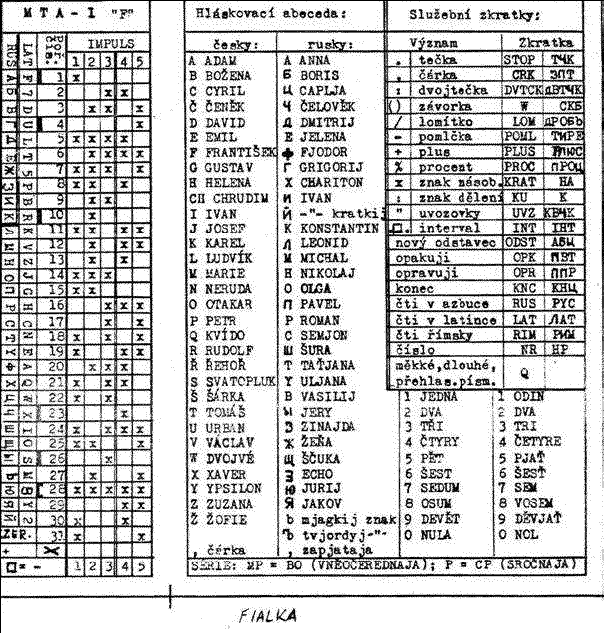

Encoder of the time of the Second World War, but about which it is impossible not to write

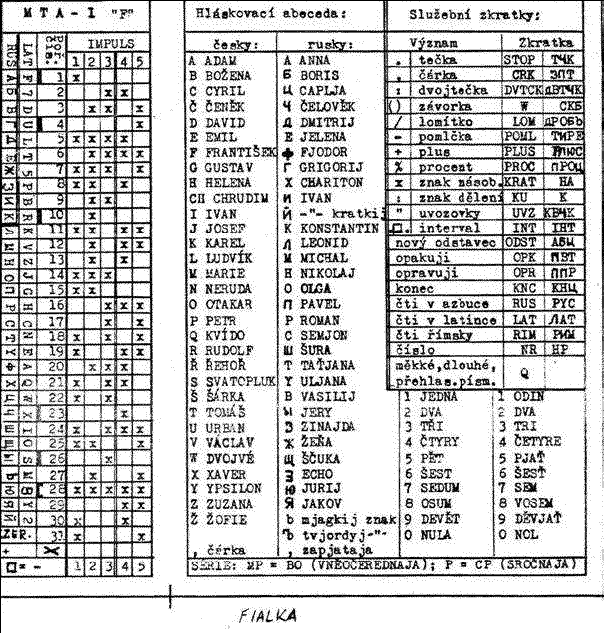

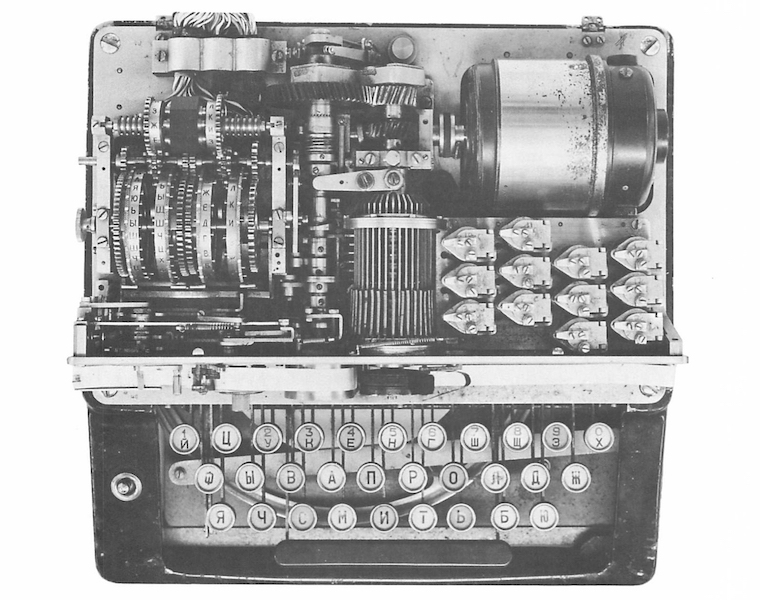

M-125 "Violet"

A series of successors to the K-37 - rotary cryptographic machines appeared in 1962, the most famous was the 10-rotor M-125 "Violet" , which the USSR supplied to the allies. Violet is often considered the “granddaughter” of Enigma, although there are fewer disks in it, and the wheels rotate in one direction. In addition to the punch cards, letter keys are used, each disk has its own letter, disks on the shaft are respectively typed, then, according to another key, they are put in a specific sequence by rotation. This model is free from the lack of Enigma - the exclusion of the possibility of encrypting a letter by itself. The amazing engineering work with the romantic name "Violet" - the Soviet encryption machine, created in the 1950s, remained unbroken, the highest achievement of engineering for intelligence and counterintelligence.

Cryptographic historian Leonid Butyrsky:

At present, in Russia, as in the rest of the world, there is a partial “discovery” of cryptography, which is increasingly being used for public purposes. Foreign achievements in the field of information protection are widely known. But this is due only to the persistence of foreign historiographers, whose publications in open sources tell about the achievements and contributions of their compatriots to this once secret area. Very interesting books are published abroad on this topic, even video series are being filmed.

Russian historians for a number of reasons, not only financial ones, lag far behind such practices of the leading countries in the development of cryptography. The possibilities of partial declassification and public coverage of the scientific and practical achievements of domestic cryptography, including the activities of iconic figures, are far from being fully utilized.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/368663/

All Articles